Artistic Influence, Stylistic Irony, and Musical Reference in Dmitri Shostakovich’S Cello Concerto No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

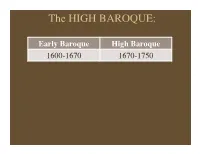

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival

Media contacts Linda Moxley, VP of Marketing & Communications 410.783.8020 [email protected] Devon Maloney, Director of Communications 410.783.8071 [email protected] For Immediate Release Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival Baltimore (April 18, 2019) Under the leadership of Music Director Marin Alsop, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) announces the 2019 New Music Festival. Launched by Alsop and the BSO in 2017, the New Music Festival brings contemporary classical music to Baltimore from June 19-22. The 2019 New Music Festival celebrates women composers ahead of the BSO’s 2019-20 season, which highlights women in music in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the U.S. Performances include the Baltimore premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Low Brass Concerto, a BSO co- commission, as well as the world premiere of Anna Clyne’s cello concerto, Dance, with Inbal Segev. “I’m thrilled that this year’s New Music Festival features such an outstanding group of contemporary composers, who happen to be women!” said Alsop. “Each piece of music that we’ve programmed tells a unique and compelling story, and we are proud to present a range of voices and perspectives that showcases some of the most inspired work happening in classical composition today.” The 2019 New Music Festival kicks off on Wednesday, June 19 when composer Sarah Kirkland Snider participates in a discussion on her composition process at Red Emma’s Bookstore Café. On Thursday, June 20, Associate Conductor Nicholas Hersh leads members of the BSO and Shara Nova, also known as My Brightest Diamond, in a free concert at the Ottobar. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Audition Requirements

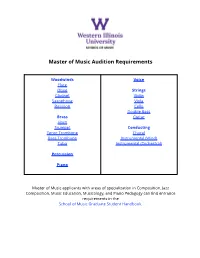

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S