Arxiv:2002.03434V3 [Physics.Flu-Dyn] 25 Jul 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accurate Modelling of Uni-Directional Surface Waves

Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 234 (2010) 1747–1756 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cam Accurate modelling of uni-directional surface waves E. van Groesen a,b,∗, Andonowati a,b,c, L. She Liam a, I. Lakhturov a a Applied Mathematics, University of Twente, The Netherlands b LabMath-Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia c Mathematics, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: This paper shows the use of consistent variational modelling to obtain and verify an Received 30 November 2007 accurate model for uni-directional surface water waves. Starting from Luke's variational Received in revised form 3 July 2008 principle for inviscid irrotational water flow, Zakharov's Hamiltonian formulation is derived to obtain a description in surface variables only. Keeping the exact dispersion Keywords: properties of infinitesimal waves, the kinetic energy is approximated. Invoking a uni- AB-equation directionalization constraint leads to the recently proposed AB-equation, a KdV-type Surface waves of equation that is also valid on infinitely deep water, that is exact in dispersion for Variational modelling KdV-type of equation infinitesimal waves, and that is second order accurate in the wave height. The accuracy of the model is illustrated for two different cases. One concerns the formulation of steady periodic waves as relative equilibria; the resulting wave profiles and the speed are good approximations of Stokes waves, even for the Highest Stokes Wave on deep water. A second case shows simulations of severely distorting downstream running bi-chromatic wave groups; comparison with laboratory measurements show good agreement of propagation speeds and of wave and envelope distortions. -

Transport Due to Transient Progressive Waves of Small As Well As of Large Amplitude

This draft was prepared using the LaTeX style file belonging to the Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1 Transport due to Transient Progressive Waves Juan M. Restrepo1,2 , Jorge M. Ram´ırez 3 † 1Department of Mathematics, Oregon State University, Corvallis OR 97330 USA 2Kavli Institute of Theoretical Physics, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara CA 93106 USA. 3Departamento de Matem´aticas, Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Medell´ın, Medell´ın Colombia (Received xx; revised xx; accepted xx) We describe and analyze the mean transport due to numerically-generated transient progressive waves, including breaking waves. The waves are packets and are generated with a boundary-forced air-water two-phase Navier Stokes solver. The analysis is done in the Lagrangian frame. The primary aim of this study is to explain how, and in what sense, the transport generated by transient waves is larger than the transport generated by steady waves. Focusing on a Lagrangian framework kinematic description of the parcel paths it is clear that the mean transport is well approximated by an irrotational approximation of the velocity. For large amplitude waves the parcel paths in the neighborhood of the free surface exhibit increased dispersion and lingering transport due to the generation of vorticity. Armed with this understanding it is possible to formulate a simple Lagrangian model which captures the transport qualitatively for a large range of wave amplitudes. The effect of wave breaking on the mean transport is accounted for by parametrizing dispersion via a simple stochastic model of the parcel path. The stochastic model is too simple to capture dispersion, however, it offers a good starting point for a more comprehensive model for mean transport and dispersion. -

The Stokes Drift in Ocean Surface Drift Prediction

EGU2020-9752 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-9752 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. The Stokes drift in ocean surface drift prediction Michel Tamkpanka Tamtare, Dany Dumont, and Cédric Chavanne Université du Québec à Rimouski, Institut des Sciences de la mer de Rimouski, Océanographie Physique, Canada ([email protected]) Ocean surface drift forecasts are essential for numerous applications. It is a central asset in search and rescue and oil spill response operations, but it is also used for predicting the transport of pelagic eggs, larvae and detritus or other organisms and solutes, for evaluating ecological isolation of marine species, for tracking plastic debris, and for environmental planning and management. The accuracy of surface drift forecasts depends to a large extent on the quality of ocean current, wind and waves forecasts, but also on the drift model used. The standard Eulerian leeway drift model used in most operational systems considers near-surface currents provided by the top grid cell of the ocean circulation model and a correction term proportional to the near-surface wind. Such formulation assumes that the 'wind correction term' accounts for many processes including windage, unresolved ocean current vertical shear, and wave-induced drift. However, the latter two processes are not necessarily linearly related to the local wind velocity. We propose three other drift models that attempt to account for the unresolved near-surface current shear by extrapolating the near-surface currents to the surface assuming Ekman dynamics. Among them two models consider explicitly the Stokes drift, one without and the other with a wind correction term. -

Part II-1 Water Wave Mechanics

Chapter 1 EM 1110-2-1100 WATER WAVE MECHANICS (Part II) 1 August 2008 (Change 2) Table of Contents Page II-1-1. Introduction ............................................................II-1-1 II-1-2. Regular Waves .........................................................II-1-3 a. Introduction ...........................................................II-1-3 b. Definition of wave parameters .............................................II-1-4 c. Linear wave theory ......................................................II-1-5 (1) Introduction .......................................................II-1-5 (2) Wave celerity, length, and period.......................................II-1-6 (3) The sinusoidal wave profile...........................................II-1-9 (4) Some useful functions ...............................................II-1-9 (5) Local fluid velocities and accelerations .................................II-1-12 (6) Water particle displacements .........................................II-1-13 (7) Subsurface pressure ................................................II-1-21 (8) Group velocity ....................................................II-1-22 (9) Wave energy and power.............................................II-1-26 (10)Summary of linear wave theory.......................................II-1-29 d. Nonlinear wave theories .................................................II-1-30 (1) Introduction ......................................................II-1-30 (2) Stokes finite-amplitude wave theory ...................................II-1-32 -

Variational Principles for Water Waves from the Viewpoint of a Time-Dependent Moving Mesh

Variational principles for water waves from the viewpoint of a time-dependent moving mesh Thomas J. Bridges & Neil M. Donaldson Department of Mathematics, University of Surrey, Guildford, GU2 7XH, UK May 21, 2010 Abstract The time-dependent motion of water waves with a parametrically-defined free surface is mapped to a fixed time-independent rectangle by an arbitrary transformation. The emphasis is on the general properties of transformations. Special cases are algebraic transformations based on transfinite interpolation, conformal mappings, and transformations generated by nonlinear elliptic PDEs. The aim is to study the effect of transformation on variational principles for water waves such as Luke’s Lagrangian formulation, Zakharov’s Hamiltonian formulation, and the Benjamin-Olver Hamiltonian formulation. Several novel features are exposed using this approach: a conservation law for the Jacobian, an explicit form for surface re-parameterization, inner versus outer variations and their role in the generation of hidden conservation laws of the Laplacian, and some of the differential geometry of water waves becomes explicit. The paper is restricted to the case of planar motion, with a preliminary discussion of the extension to three-dimensional water waves. 1 Introduction In the theory of water waves, the fluid domain shape is changing with time. Therefore it is appealing to transform the moving domain to a fixed domain. This approach, first for steady waves and later for unsteady waves, has been widely used in the study of water waves. However, in all cases the transformation is either algebraic (explicit) or a conformal mapping. In this paper we look at the equations governing the motion of water waves from the viewpoint of an arbitrary time-dependent transformation of the form x(µ,ν,τ) (µ,ν,τ) y(µ,ν,τ) , (1.1) 7→ t(τ) where (µ,ν) are coordinates for a fixed time-independent rectangle D := (µ,ν) : 0 µ L and h ν 0 , (1.2) { ≤ ≤ − ≤ ≤ } with h, L given positive parameters. -

Waves on Deep Water, I

Lecture 14: Waves on deep water, I Lecturer: Harvey Segur. Write-up: Adrienne Traxler June 23, 2009 1 Introduction In this lecture we address the question of whether there are stable wave patterns that propagate with permanent (or nearly permanent) form on deep water. The primary tool for this investigation is the nonlinear Schr¨odinger equation (NLS). Below we sketch the derivation of the NLS for deep water waves, and review earlier work on the existence and stability of 1D surface patterns for these waves. The next lecture continues to more recent work on 2D surface patterns and the effect of adding small damping. 2 Derivation of NLS for deep water waves The nonlinear Schr¨odinger equation (NLS) describes the slow evolution of a train or packet of waves with the following assumptions: • the system is conservative (no dissipation) • then the waves are dispersive (wave speed depends on wavenumber) Now examine the subset of these waves with • only small or moderate amplitudes • traveling in nearly the same direction • with nearly the same frequency The derivation sketch follows the by now normal procedure of beginning with the water wave equations, identifying the limit of interest, rescaling the equations to better show that limit, then solving order-by-order. We begin by considering the case of only gravity waves (neglecting surface tension), in the deep water limit (kh → ∞). Here h is the distance between the equilibrium surface height and the (flat) bottom; a is the wave amplitude; η is the displacement of the water surface from the equilibrium level; and φ is the velocity potential, u = ∇φ. -

0123737354Fluidmechanics.Pdf

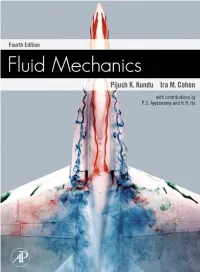

Fluid Mechanics, Fourth Edition Founders of Modern Fluid Dynamics Ludwig Prandtl G. I. Taylor (1875–1953) (1886–1975) (Biographical sketches of Prandtl and Taylor are given in Appendix C.) Photograph of Ludwig Prandtl is reprinted with permission from the Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 19, Copyright 1987 by Annual Reviews www.AnnualReviews.org. Photograph of Geoffrey Ingram Taylor at age 69 in his laboratory reprinted with permission from the AIP Emilio Segre` Visual Archieves. Copyright, American Institute of Physics, 2000. Fluid Mechanics Fourth Edition Pijush K. Kundu Oceanographic Center Nova Southeastern University Dania, Florida Ira M. Cohen Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with contributions by P. S. Ayyaswamy and H. H. Hu AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400 Burlington, MA 01803, USA Elsevier, The Boulevard, Langford Lane Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK © 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). -

Stokes Drift and Net Transport for Two-Dimensional Wave Groups in Deep Water

Stokes drift and net transport for two-dimensional wave groups in deep water T.S. van den Bremer & P.H. Taylor Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford [email protected], [email protected] Introduction This paper explores Stokes drift and net subsurface transport by non-linear two-dimensional wave groups with realistic underlying frequency spectra in deep wa- ter. It combines analytical expressions from second- order random wave theory with higher order approxi- mate solutions from Creamer et al (1989) to give accu- rate subsurface kinematics using the H-operator of Bate- man, Swan & Taylor (2003). This class of Fourier series based numerical methods is extended by proposing an M-operator, which enables direct evaluation of the net transport underneath a wave group, and a new conformal Figure 1: Illustration of the localized irrotational mass mapping primer with remarkable properties that removes circulation moving with the passing wave group. The the persistent problem of high-frequency contamination four fluxes, the Stokes transport in the near surface re- for such calculations. gion and in the direction of wave propagation (left to Although the literature has examined Stokes drift in right); the return flow in the direction opposite to that regular waves in great detail since its first systematic of wave propagation (right to left); the downflow to the study by Stokes (1847), the motion of fluid particles right of the wave group; and the upflow to the left of the transported by a (focussed) wave group has received con- wave group, are equal. siderably less attention. -

Final Program

Final Program 1st International Workshop on Waves, Storm Surges and Coastal Hazards Hilton Hotel Liverpool Sunday September 10 6:00 - 8:00 p.m. Workshop Registration Desk Open at Hilton Hotel Monday September 11 7:30 - 8:30 a.m. Workshop Registration Desk Open 8:30 a.m. Welcome and Introduction Session A: Wave Measurement -1 Chair: Val Swail A1 Quantifying Wave Measurement Differences in Historical and Present Wave Buoy Systems 8:50 a.m. R.E. Jensen, V. Swail, R.H. Bouchard, B. Bradshaw and T.J. Hesser Presenter: Jensen Field Evaluation of the Wave Module for NDBC’s New Self-Contained Ocean Observing A2 Payload (SCOOP 9:10 a.m. Richard Bouchard Presenter: Bouchard A3 Correcting for Changes in the NDBC Wave Records of the United States 9:30 a.m. Elizabeth Livermont Presenter: Livermont 9:50 a.m. Break Session B: Wave Measurement - 2 Chair: Robert Jensen B1 Spectral shape parameters in storm events from different data sources 10:30 a.m. Anne Karin Magnusson Presenter: Magnusson B2 Open Ocean Storm Waves in the Arctic 10:50 a.m. Takuji Waseda Presenter: Waseda B3 A project of concrete stabilized spar buoy for monitoring near-shore environement Sergei I. Badulin, Vladislav V. Vershinin, Andrey G. Zatsepin, Dmitry V. Ivonin, Dmitry G. 11:10 a.m. Levchenko and Alexander G. Ostrovskii Presenter: Badulin B4 Measuring the ‘First Five’ with HF radar Final Program 11:30 a.m. Lucy R Wyatt Presenter: Wyatt The use and limitations of satellite remote sensing for the measurement of wind speed and B5 wave height 11:50 a.m. -

Answers of the Reviewers' Comments Reviewer #1 —- General

Answers of the reviewers’ comments Reviewer #1 —- General Comments As a detailed assessment of a coupled high resolution wave-ocean modelling system’s sensitivities in an extreme case, this paper provides a useful addition to existing published evidence regarding coupled systems and is a valid extension of the work in Staneva et al, 2016. I would therefore recommend this paper for publication, but with some additions/corrections related to the points below. —- Specific Comments Section 2.1 Whilst this information may well be published in the authors’ previous papers, it would be useful to those reading this paper in isolation if some extra details on the update frequencies of atmosphere and river forcing data were provided. Authors: More information about the model setup, including a description of the open boundary forcing, atmospheric forcing and river runoff, has been included in Section 2.1. Additional references were also added. Section 2.2 This is an extreme case in shallow water, so please could the source term parameterizations for bottom friction and depth induced breaking dissipation that were used in the wave model be stated? Authors: Additional information about the parameterizations used in our model setup, including more references, was provided in Section 2.2. Section 2.3 I found the statements that "<u> is the sum of the Eulerian current and the Stokes drift" and "Thus the divergence of the radiation stress is the only (to second order) force related to waves in the momentum equations." somewhat contradictory. In the equations, Mellor (2011) has been followed correctly and I see the basic point about radiation stress being the difference between coupled and uncoupled systems, so just wondering if the authors can review the text in this section for clarity. -

On the Transport of Energy in Water Waves

On The Transport Of Energy in Water Waves Marshall P. Tulin Professor Emeritus, UCSB [email protected] Abstract Theory is developed and utilized for the calculation of the separate transport of kinetic, gravity potential, and surface tension energies within sinusoidal surface waves in water of arbitrary depth. In Section 1 it is shown that each of these three types of energy constituting the wave travel at different speeds, and that the group velocity, cg, is the energy weighted average of these speeds, depth and time averaged in the case of the kinetic energy. It is shown that the time averaged kinetic energy travels at every depth horizontally either with (deep water), or faster than the wave itself, and that the propagation of a sinusoidal wave is made possible by the vertical transport of kinetic energy to the free surface, where it provides the oscillating balance in surface energy just necessary to allow the propagation of the wave. The propagation speed along the surface of the gravity potential energy is null, while the surface tension energy travels forward along the wave surface everywhere at twice the wave velocity, c. The flux of kinetic energy when viewed traveling with a wave provides a pattern of steady flux lines which originate and end on the free surface after making vertical excursions into the wave, even to the bottom, and these are calculated. The pictures produced in this way provide immediate insight into the basic mechanisms of wave motion. In Section 2 the modulated gravity wave is considered in deep water and the balance of terms involved in the propagation of the energy in the wave group is determined; it is shown again that vertical transport of kinetic energy to the surface is fundamental in allowing the propagation of the modulation, and in determining the well known speed of the modulation envelope, cg. -

NONLINEAR DISPERSIVE WAVE PROBLEMS Thesis by Jon

NONLINEAR DISPERSIVE WAVE PROBLEMS Thesis by Jon Christian Luke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 1966 (Submitted April 4, 1966) -ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author expresses his thanks to Professor G. B. Whitham, who suggested the problems treated in this dissertation, and has made available various preliminary calculations, preprints of papers, and lectur~ notes. In addition, Professor Whitham has given freely of his time for useful and enlightening discussions and has offered timely advice, encourageme.nt, and patient super vision. Others who have assisted the author by suggestions or con structive criticism are Mr. G. W. Bluman and Mr. R. Seliger of the California Institute of Technology and Professor J. Moser of New York University. The author gratefully acknowledges the National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship that made possible his graduate education. J. C. L. -iii ABSTRACT The nonlinear partial differential equations for dispersive waves have special solutions representing uniform wavetrains. An expansion procedure is developed for slowly varying wavetrains, in which full nonl~nearity is retained but in which the scale of the nonuniformity introduces a small parameter. The first order results agree with the results that Whitham obtained by averaging methods. The perturbation method provides a detailed description and deeper understanding, as well as a consistent development to higher approximations. This method for treating partial differ ential equations is analogous to the "multiple time scale" meth ods for ordinary differential equations in nonlinear vibration theory. It may also be regarded as a generalization of geomet r i cal optics to nonlinear problems.