Legacy of a Lynching Columbia Remembers Racial Injustice by BARTON GROVER HOWE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumford, Frederick Blackmar, Papers, 1944 (C3455)

C Mumford, Frederick Blackmar, Papers, 1944 3455 1 linear foot This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The papers of Frederick Mumford contain reports, notes, documents, data and correspondence, most of which was used by Dean Mumford in preparation of his book, History of the Missouri College of Agriculture, published in 1944 as “Bulletin” 483 of the Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were donated to the State Historical Society of Missouri by the College of Agriculture, 18 September 1962 (No. 121). BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Frederick Blackmar Mumford, who compiled information for a book, History of the Missouri College of Agriculture, was dean of the College of Agriculture from 1909 to 1938. He was born in Moscow, Michigan, May 28, 1868, and died in St. Charles, Missouri, November 12, 1946. His education included a degree from Michigan State Agricultural College and graduate work at the Universities of Leipsig and Zurich. He came to the University of Missouri in 1895 as professor of agriculture and became professor of animal husbandry in 1905. FOLDER LIST f. 1-10 Early movements for agricultural education; Morrill Acts, 1862, 1890 f. 11-12 Organization of the Missouri College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts f. 13-21 Administrations of the first five deans of the Missouri College of Agriculture- Dean George C. Swallow, Dean J.W. Sanborn, Dean Henry J. Waters, Dean Frederick B. Mumford f. 22 Relations between the Missouri Board of Agriculture and the Missouri College of Agriculture f. -

Special Collections University of Missouri-Columbia Libraries Columbia, Missouri 2001 Contents

DIRECTORY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-COLUMBIA LllRARIES COMPILED BY MARGARET A. HOWELL SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI-COLUMBIA LIBRARIES COLUMBIA, MISSOURI 2001 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Rare Book Collection 3 University of Missouri Collection 7 Comic Art Collection 9 Frank Luther Mott Collection of Early American Best Sellers 10 Weinberg Journalists in Fiction Collection 11 William H. Peden Short Story Collection 12 John G. Neihardt Collection 13 Historic Textbook Collection 15 Mary Lago Collection 16 Thomas Moore Johnson Collection of Philosophy 18 Closed Collection 19 Playbill Collection 20 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Missouri Collection 21 War Poster Collection 23 Columbia Missourian Newspaper Library 24 Donald Silver, M.D., Rare Book Room 25 University Archives 27 INTRODUCTION pecial Collections in the MU Libraries are almost as old as the Libraries them Sselves. The genesis of the present-day Special Collections Division began with a small collection of rare books housed in the office of the Director of Libraries. Since then the Rare Book Collection in Ellis Library has grown both by design and through donations, and the Health Science Library's Rare Book Collection has de veloped similarly. ift collections of philosophy books, short stories, early American best sellers, G and early elementary and secondary textbooks have enriched the holdings of Special Collections. The Comic Art Collection also contains numerous important gifts that complement and enhance purchased titles. The University of Missouri Collection contains published works by and about the University and its faculty, while the University Archives maintain the University'S official records and publi cations. -

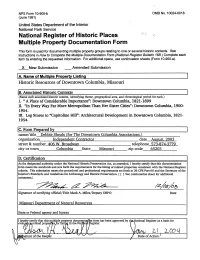

National Register of Historic Places ? Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 10024-0018 (June 1991) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places ? Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B.) Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). X New Submission Amended Submission i Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of Downtown Columbia, Missouri < Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) I. " A Place of Considerable Importance": Downtown Columbia, 1821-1899 IL "In Every Way Far More Metropolitan Than Her Sister Cities": Downtown Columbia, 1900- 1^54. III. Log Stores to "Capitoline Hill": Architectural Development in Downtown Columbia, 1821- 1^54. C. Form Prepared by name/tide Pebble Sheals ffor The Downtown Columbia Associations.)__________________ organization____Independent Contractor_____________ date August, 2003 stjreet & number 406 W. Broadway________________ telephone 573-874-3779 city or town_____Columbia State Missouri____ zip code 65203_______ D; Certification As! the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the standards and sets forth the requirements for the Usting of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. ( [ ] See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Mark A. -

Faculty~Alumni Awards

Faculty~Alumni Awards 2013 46th Faculty~Alumni Awards 54th Distinguished Faculty Award 58th Distinguished Service Award Mission Statement The Mizzou Alumni Association proudly supports the best interests and traditions of Missouri’s flagship university and its alumni worldwide. Lifelong relationships are the foundation of our support. These relationships are enhanced through advocacy, communication and volunteerism. Fellow Tigers, I join you in celebrating the extraordinary contri- GOVERNING butions of this evening’s Faculty-Alumni Award BOARD recipients, the Distinguished Faculty Award recipi- Tracey E. Mershon, President ent and the Distinguished Service Award recipient. W. Dudley The Alumni Association’s tradition of recognizing McCarter, President-Elect excellence started back in 1956 and continues today with this year’s Sherri Gallick, outstanding class of awardees. We come together this evening to ex- Vice President press our admiration and appreciation for these faculty and alumni Ted Ayres, Treasurer who have brought distinction upon themselves and our University. James B. Gwinner, Congratulations, Immediate Past Todd McCubbin, Executive Director President Mizzou Alumni Association Mark Bauer Jill Brown Hsu Hua Christine Dear Fellow Alumni and Friends, Chan To be selected to receive a Faculty-Alumni Award is a Wiliam Fialka tremendous honor and I am proud to extend my con- Julie Gates gratulations from the University of Missouri Alumni Christina Hammers Association Governing Board on behalf of more than Matthew Krueger Lesa McCartney 260,000 alumni worldwide. We thank you for your Ellie Miller contributions to the arts and sciences, to business and industry, and Rachel Newman, the support you have shown your University. Your achievements have Student Rep. -

MISSOURI TIMES the State Historical Society of Missouri February 2011 Vol

MISSOURI TIMES The State Historical Society of Missouri February 2011 Vol. 6, No. 4 From the President Society greatly expands digital collections, acquires four-campus Western Historical Manuscript Collection, and tightens fiscal belt On January 10 the Society announced the digital launch of six collections that placed thousands of historically significant documents, Online Photos, Art, photographs, newspapers and artworks online, Newspapers, Cartoons including over 400 artworks by Missouri’s two Pages 2-3 most famous artists, George Caleb Bingham and Thomas Hart Benton; more than 13,000 editorial cartoons by Bill Mauldin, Daniel Fitzpatrick, and Tom Engelhardt; 3,500 photographs of Missouri places and people; more than 1,950 issues of the In consultation with our board, the executive St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican from the Civil director, and University of Missouri leadership, War years (1861-1865); the Columbia Missourian, I signed a Memorandum of Understanding 1908-1922; and 150 transcript and audio files of with then University President Gary Forsee, in interviews held with Missouri political leaders early January, for the Society to assume sole since 1996. management of WHMC. With best practices These collections add to materials made Gift of Hoberg Letters in mind, we will fulfill all research requests and available online in 2010, which included Page 4 information queries concerning the manuscript thousands of Civil War-era documents and collections. the Society’s award-winning journal, Missouri To faciliatate our meeting those service goals, Historical Review, from 1906 to 2001. the Society was closed to the public January 11- Digitization of collections occurred through 15, 2011, for staff members to properly arrange nearly a half-million dollars in grants from the combined services in the Research Center external funding organizations, including within the Society’s quarters. -

Turn Your Radio On, Columbia Mellow and Medium-Temp- O Rock Between 12 A.M

0 W B 1982-P- age i U & I COLUMBIA MISSOURIAN, Friday, April 9, 4B Turn your radio on, Columbia mellow and medium-temp- o rock between 12 a.m. smooth flow in their programming and to make and 6 a.m. the station easy to listen to. Segue describes the The Dirt Band, Willie Music, programs Though KCMQ also emphasizes continuously-playin- g creative blending of two units. It is the disc jock- music, disc jockey Larry Cannger hosts a ey's responsibility to blend songs together in humorous morning wake-u- p show, and disc jockey terms of type of music and tempo so the sound show diversity Bruce Jones hosts an afternoon talk show. flows smoothly. Thus, The Police, with their reg- Nelson come to town gae sound might be played after Stevie Wonder, Ma-mlo- Columbia is on a roll. The Willie who but Led Zeppelin would never follow Barry w. other is Nelson, KBIA 91.3 FM The sounds of Alabama are still will perform at Hearnes at 8 p.m. two of area's stations Many stations in Columbia offer jazz. KBIA of- Donegan says he believes KCOU has something echoing on the stage, but other April 23. fers azz with a twist. Though KBIA's music for- for everyone. The station offers reggae, blues, big-na- me entertainment groups are Nelson, the only country artist to By Michael Pritchett mat is split between classical music and jazz mu- already scheduled in town. sell out two shows per night for two Missourian staff writer soul and jazz programs in addition to its predomi- sic, the station offers all sounds for the jazz nantly rock 'n' roll format. -

University of Missouri

Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri University of Missouri A Journal of Undergraduate Writing Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence Lauren Reagan When prospective students first tour the University of Missouri-Columbia’s campus, they are thinking about academic programs, Tiger football, and the incredible recreational center. The last thing that crosses a student’s mind is being in danger, and tour guides are not likely to mention campus violence. When parents bring up safety issues, the emergency call system and campus police force assures them, and the problems Mizzou faces with assault, rape and robbery can be ignored. In accordance with the Clery Act, the University of Missouri must send students emails every time a violent act occurs on campus (Evaluation of Green Dot 777). For most MU students, this is the first they hear of campus danger. Many factors such as gender roles, alcohol use and societal norms lead to violence on Mizzou’s campus. These crimes cause not only physical, but also emotional and mental damage to victims, and students are beginning to protest. The Maneater published an editorial urging students to take a stand against violence, and former MSA president, Xavier Billingsely, sent a mass email in November 2012 urging the same. Current university prevention programs are simply not producing enough results. It is time for students, faculty and community members to change how violence is addressed. http://artifactsjournal.missouri.edu/2013/05/our-home-away-from-home-putting-a-stop-to-college-campus-violence/[9/15/2014 1:13:04 PM] Our Home Away From Home: Putting a Stop to College Campus Violence – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri College campuses can be a breeding ground for violence, and a place society expects to be a learning community can become extremely dangerous. -

MIPA Member Benefits.Newfonts.Indd

High School Journalism Teacher and Publication Adviser Resources Offered by the Missouri Interscholastic Press Association and the Missouri School of Journalism MIPA: Missouri: Your Connection Your Partner to Resources, in Scholastic Opportunities Journalism Teachers seem to be always looking The Missouri School of Journalism for that next great lesson plan to light welcomes opportunities to help high their students’ passion for journalism school journalism teachers and yearbook or a bit of training so they can stay advisers. Speakers, workshops, campus sharp. Membership in the Missouri visits and webinars are some of the ways Interscholastic Press Association you can bring the resources of the world’s J-Day, held at the University of Missouri in provides these benefi ts and more. late March, is a full day of speakers, work- journalism school to your classroom. shops, awards and fun. More than 1,500 stu- Since 1923, the Missouri dents across the state participate each year. The School has trained some of the Interscholastic Press Association has best journalists in the world through the partnered with the Missouri School at the top of their game within the Missouri Method, which provides practical of Journalism at the University profession, workshops, vendors – and hands-on training in real-world news me- of Missouri. As a MIPA member loads of fun. dia and strategic communication agencies: you will have access to a wealth of Columbia Missourian, KOMU-TV, KBIA- resources, including two websites As 21st century learners, your FM, Vox Magazine, Global Journalist, with time-saving lessons and students need to meet a myriad of Missouri Business Alert - and two strategic resource materials, a mentor program, objectives, standards and curriculum communication agencies - AdZou and speakers, professional development goals. -

Missouri Newsnews

MissouriMissouri NewsNews Your inside story for Press October 2003 Journalism School 9 may get vacant building. 10 St. Louis American receives Missouri Honor Medal. (School of Journalism photo) Contest awards presented in Kansas City. A list of winners City honors a favorite son is inside. The community of Boonville unveiled a bust of Walter Williams, the first 19 dean of the Missouri School of Journalism, on Sept. 14. Sculptor Sabra Tull Meyer was among those attending the ceremony. An account of the event with more photos is on page 8. (Photo by Jim Sterling) Regular Jean Maneke 24 Features Obituaries 25 President 2 Housekeeping 26 On the Move 13 Kitchell on NIE 27 Scrapbook 16 Nostalgia 29 www.mopress.com Survey should help sell ads Candidates would do well to include newspapers in campaigns e have much cause to have faith in the efforts of our ahead of all but one source of information for help in deciding More in ’04 committee to garner more political ad- how to vote, so keep publishing those political stories (not to be Wvertising for Missouri newspapers. confused with candidate news releases). Only voter pamphlets Of course, no one should expect us to turn the world upside rank ahead of newspaper articles, but don’t mistake that for an down overnight. We didn’t get in the position we are in over the endorsement of direct mail. Only television news finished below span of two years or even four years. Decades of take-it-for- brochures mailed directly to the home. granted attitude on our part got us to where we The survey also identifies newspapers as be- are and it will take decades of hard work to ing a great source for reaching the 39 percent change it. -

The 2015 University of Missouri Protests and Their Lessons for Higher Education Policy and Administration

University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2018 The 2015 niU versity of Missouri Protests and their Lessons for Higher Education Policy and Administration Ben L. Trachtenberg University of Missouri School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation Ben L. Trachtenberg, The 2015 nivU ersity of Missouri Protests and their Lessons for Higher Education Policy and Administration, 107 Kentucky Law Journal 61 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs/740 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 2015 University of Missouri Protests and their Lessons for Higher Education Policy and Administration Ben Trachtenberg' ABSTRACT In 2015, student protestors at more than eighty American universities issued administratorsdemands related to racialjustice. Even readers intensely interested in both civil rights and higher educationpolicy could name few ofthese institutions. Yet somehow the University of Missouri ("Mizzou")-along with Yale and a few other universities-became nationallyfamous as a hotbed of racial unrest. At most ofthese eighty universities, presidents did not resign, enrollment did not plummet by thousands of students, nor did relationswith state politiciansdeteriorate terribly. In the traditionof legal narrative and storytelling, this Article explores how the University of Missouri managed to fare so badly after students began protesting during the fall of 2015. -

MU-Map-0150-Front.Pdf (4.385Mb)

Welcome to ... The University of Missouri-Columbia Tomorrow, today, and yesterday are merged in •the history addition to the east was completed in 1962, to make the and development of the University of Missouri, established in Library one of the largest in the nation. Columbia in 1839, only 18 years after Missouri was admitted to The Business and Public Administration building at South statehood. Ninth Street and University Avenue, and a Fine Arts Center for The much-loved Columns-symbol of the past-stand majes- art, music, and the dramatic arts, located on Hitt Street across tically today with new space-age Research Park, where major from the Memorial Union are also in the central campus area. facilities include a IO-megawatt nuclear reactor, one of the largest university-owned in the United States. The "White" Campus The Columbia campus ( oldest and largest of the Universi- The main entrance to the east campus, more commonly ty's four campuses) is unique in having 16 divisions. known as the "white" campus, is through Memorial Tower, dedicated in 1926 as a memorial to University students who Francis Quadrangle gave their lives in World War I. The north wing of the Memorial The University of Missouri was established 132 years ago by Union honoring students who died in World War II was an act modeled after a Virginia statute, drafted and sponsored completed in 1952, and the south wing was finished in 1963. by Thomas Jefferson, which 20 years earlier had created the Adjacent to, and east of, the center tower is the non-denomina- University of Virginia. -

Today's Weather Have You Heard?

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RSS A daily rundown of news at the University of Missouri, presented View this email in your by Mizzou Student Media. browser Monday, March 14, 2016 Today's Weather Hold the phone; there’s no rain in the forecast for today. Temps will be in the 70s. Woohoo! Have You Heard? Columbia Misssourian: Candidate stances clash at City Council forum The hot topics of Columbia — parking, housing, infrastructure, police funding — were discussed Sunday at a forum hosted by the Columbia Missourian and the Columbia Daily Tribune. The exchange between the Fourth Ward candidates was testy. Incumbent Ian Thomas is facing Daryl Dudley, who lost to Thomas in 2013. The two differ on transparency, among other issues. Gallery: MizzouThon raises $276,664.11 MizzouThon participants continued their streak of raising record amounts for the MU Children’s Hospital. Last year, they raised $201,322.68. Their fundraising efforts culminated this weekend with a 13.1-hour dance marathon. What you need to know about the House's vote on the budget The $8.6 million in budget cuts first announced at the end of February were passed by the Missouri House of Representatives last week. During the debate on the House floor, one lawmaker referred to MU as a “resort” and said the university shouldn’t fret over the loss of funds. Rep. Caleb Jones, R-Columbia, was the only area lawmaker to vote for the cuts. Let's dig a little deeper. In April, Columbia voters will put a new mayor in office, a seat occupied by Bob McDavid for the last six years.