Full Text E-Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BENDIGO BOMBERS Coach: ADRIAN HICKMOTT

VFL squads CAPTAIN: JAMES FLAHERTY BENDIGO BOMBERS Coach: ADRIAN HICKMOTT No. Name DOB HT WT Previous clubs G B 1 Jay Neagle * 17/01/88 191 100 gippsland Power/Traralgon 2 Ricky DysoN * 28/09/85 182 82 Northern Knights/epping 3 Paul scaNloN 19/10/77 178 85 seymour/ Northern Bullants (VFl) 4 simon DaVies 30/09/89 176 78 North shore 5 stewart CrameRi 10/08/88 187 95 maryborough 6 Josh Bowe 25/06/87 176 79 Bendigo Pioneers/eaglehawk 7 leroy Jetta * 06/07/88 178 75 south Fremantle (WA) 9 Brent PRismall * 14/07/86 186 82 geelong/western Jets/werribee 10 Blair Holmes 18/05/89 176 80 Bendigo Pioneers/sandhurst 11 David ZaHaRaKis * 21/02/90 182 76 Northern Knights/marcellin college/eltham 12 michael HuRley * 01/06/90 193 91 Northern Knights/macleod 13 Darren Hulme 19/07/77 170 78 clayton/carlton 14 sam loNeRgaN * 26/03/87 182 80 Tasmania (VFl)/launceston 15 Joel maloNe 10/01/84 176 80 maryborough 16 Tayte PeaRs * 24/03/90 191 91 east Perth (WA) 17 Jay NasH * 21/12/85 188 84 central District (SA) 18 simon weeKley 19/03/87 187 88 sea lake/sandhurst 19 James BRisTow 29/01/89 194 101 gippsland Power/sale 20 charles slatteRy 16/01/84 183 81 central District (SA) 21 Hayden SkiPworth * 25/02/83 177 78 Bendigo Bombers (VFl)/adelaide 22 James FlaHerty 05/11/86 188 87 south Bendigo 23 David myeRs * 30/06/89 190 85 Perth (WA) 24 John williams * 08/10/88 188 84 morningside (Qld) 25 Brent ChaPmaN 31/03/83 183 76 Barooga 26 cale HooKeR * 13/10/88 196 93 east Fremantle (WA) 27 Jason laycocK * 04/11/84 201 103 Tassie mariners/east Devonport 28 Darcy DaNiHeR * -

Until Victory Always: a Memoir Free

FREE UNTIL VICTORY ALWAYS: A MEMOIR PDF Jim McGuinness,Keith Duggan | 304 pages | 13 Dec 2015 | Gill | 9780717169375 | English | Dublin, Ireland Until Victory Always: A Memoir: Jim McGuinness is more than a football man I remember falling out of the Abbey Hotel bar in Donegal town towards dawn at the end of a long night in in the company of a college girlfriend, a local who was well used to such marathons. There was an intense Donegal mix that night of heavy drinking, sparkling wit, big heartedness, wide beautiful eyes and Ulster edginess. Yet there was also an air of Until Victory Always: A Memoir as the drinkers basked in the afterglow of winning their first All-Ireland football championship and teased me, the sole Dub. It was especially pleasing for them to be able Until Victory Always: A Memoir taunt, not just because of the long Until Victory Always: A Memoir for victory, but for other, deeper reasons that have to do with Ulster identity, the legacy of the partition of Ireland and the difficulties of being from a county that felt that partition deeply; that has often felt neglected and ignored, in but not quite of the Republic. It is a powerful book; enlightening, infuriating and emotional. The prose is woven around the sporting events of the yearsbut interspersed with memories of his childhood, adolescence and life outside the GAA cauldron, including his accomplished journey through adult education, which took him to postgraduate level. McGuinness personifies both Until Victory Always: A Memoir edginess and the warmth I remember from trips to Donegal. -

Transfer-Schedule-2010-2017A.Pdf

A I S T R I T H E I D I R C O N T A E T H E 2 0 1 7 On Hold Cleared after Ten days from date received DATE REF. NAME FROM TO Porcesse d 4.1.17 1/17 Jamie Cullen Ath Cliath Erin Go Bragh Cill Dara Ballymore Eustace 6.1.17 2/17 Paul Aylward Ath Cliath St Judes Cill Dara Ardclough 9.1.17 3/17 Fergus Barnett An Mhi St. Marys Lu Glen Emmets 9.1.17 4/17 Conor McQuail Leech An Mhi Duleek Bellewstown Lu Wolfe Tones 9.1.17 5/17 Robert Pender Cill Mhantain Blessington Cill Dara Suncroft 10.1.17 6/17 Hugh Naughton Laois Arles Killeen Cill Mhantain Coolkenno 10.1.17 7/17 Michael Bermingham Uibh Fhaili Ballinamere Laois Kilcavan 11.1.17 8/17 Patrick Lee Iarmhi Kinnegad An Mhi Ballinabrackey 11.1.17 9/17 Gavan Sweeney Lu Stabannon Parnells An Mhi St Michaels 11.1.17 10/17 Paul Donnelly Cill Chainnigh Railyard Cill Dara Kill 12.1.17 11/17 Brian Kelly An Mhi Nobber Cill Dara Cappagh 12.1.17 12/17 Raymond Campbell Longford Grattan Og Lu Oliver Plunketts 12.1.17 13/17 John Martin Loch Garman St. Patricks Lu Naomh Moninne 17.1.17 14/17 Peter Shaw Ceatharloch Naomh Brid Ath Claith Faughs DATE REF. NAME FROM TO processe d 17.1.17 15/17 Aaron Skelly (withdrawn) An Mhi St Brigids Ath Cliath Whitehall Colmcille 17.1.17 16/17 Tomas O Mahoney Loch Garman Oylegate Glenbrien Ath Cliath Realt Dearg 17.1.17 17/17 Thomas Nolan (withdrawn) Cill Dara Grange Laois Barrowhouse 17.1.17 18/17 Colin Ryan An Mhi Na Fianna Enfield Ath Cliath Na Fianna 18.1.17 19/17 James Hilliard Laois Mountmellick Ath Cliath St Marcus 18.1.17 20/17 Daniel Murphy Ath Cliath Fingal Ravens An -

{FREE} Until Victory Always: a Memoir Ebook

UNTIL VICTORY ALWAYS: A MEMOIR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jim McGuinness,Keith Duggan | 304 pages | 13 Dec 2015 | Gill | 9780717169375 | English | Dublin, Ireland Until Victory Always: A Memoir PDF Book An updated edition of one woman's hilarious journey from thin to fat and back again. Poetry: The Flourishing Shrub. My best friend. Average rating 4. More Details Read more Damien Sweeney rated it it was amazing May 30, Fighting Words Roddy Doyle introduces head-turning young Irish writing. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Women writers Putting Irish women writers back in the picture. Yet there was also an air of satisfaction as the drinkers basked in the afterglow of winning their first All-Ireland football championship and teased me, the sole Dub. Diarmaid Ferriter. The Cage, a short story by Tony Wright. Sat, Nov 7, , First published: Sat, Nov 7, , It is a powerful book; enlightening, infuriating and emotional. It was about people. Luke rated it really liked it Nov 02, Sure I have bras aulder than that" "The clock was ticking. Want to Read saving…. Everyone said this was a must read even non-readers! Overall, the book is a must read for anybody even non GAA supporters. You can curl up under a blanket defence and read Until Victory Always from 23 October. And reading how Mark died, would make the biggest religious sceptic, a believer! Retrieved 31 October Add links. More from The Irish Times Books. On 19 January Ireland was invaded by a two-month-long arctic siege that brought freezing This book is a rollercoaster of emotions. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

An Chomdhail Bhliantúil 2012

An Chomdhail Bhliantúil 2012 Tuarascáil Bhliaintúil An Runaí A Chairde, The past season has witnessed the helped to maintain government support Counties failure to win frontline for staffing costs for 2011 and 2012. Sometimes it is better to have a vision championships but Donegal did win for the future than to rely on our the Allianz Football League Division The stewards, team officials and members current or historic past. While all are 2 title as well as reaching the All- of Comhairle Uladh give an enormous important and we cannot choose to Ireland semi final where they could amount of time to act in many capacities operate with indifference to who we have succeeded against the eventual such as stiles men, stewards, counters are, where we came from or where we winners Dublin. Crossmaglen Rangers and supervisors throughout the year. We want to go and to this end we need to returned to All-Ireland Championship could not do without this outstanding input be confident of what we have achieved success and Lisnakea Emmetts also by a great team. We are also indebted to and more importantly be confident of emulated their success by winning the our staff, who have given generously of our future, of our communities and All-Ireland Intermediate title. The ladies their time in working and in a voluntary above all the inherent ability of our of Lisnaskea won the female equivalent capacity within the management and people to build a future worthy of while Sperrin Óg won the All-Ireland control of games and are actively involved the land of Saints and Scholars. -

Craobh Peile Uladh2o2o Muineachán an Cabhánversus First Round Saturday 31St October St Tiernach’S Park

CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O MUINEACHÁN AN CABHÁNVERSUS FIRST ROUND SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER ST TIERNACH’S PARK. 1.15 PM DÚN NA NGALL TÍR VERSUSEOGHAIN QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER PÁIRC MACCUMHAILL - 1.30PM DOIRE ARD VERSUSMHACHA QUARTER FINAL SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER CELTIC PARK - 4.00 PM RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE 8 The stands may be silent but we know our communities are standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 371 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From THIS WEEKEND’S (ALL GAMESGA ARE SUBJECTMES TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ STVERSUS TIERNACH’S PARK, CLONES SATURDAY 31ST OCTOBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Round 1 (1:15pm) Réiteoir: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Maor Líne: Cormac Reilly (An Mhí) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Padraig Hughes (Ard Mhacha) Maoir: Mickey Curran, Conor Curran, Marty Brady & Gavin Corrigan @ PÁIRCVERSUS MAC CUMHAILL, BALLYBOFEY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (1:30pm) Réiteoir: Joe McQuillan (An Cabhán) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: David Gough (An Mhí) Maor Líne: Barry Judge (Sligeach) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: John Gilmartin (Sligeach) Maoir: Ciaran Brady, Mickey Lee, Jimmy Galligan & TP Gray VERSUS@ CELTIC PARK, DERRY SUNDAY 1ST NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Q Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Sean Hurson (Tír Eoghain) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Martin McNally (Muineachán) Maor Líne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Niall McKenna (Muineachán) Maoir: Cathal Forbes, Martin Coney, Mel Taggart & Martin Conway 832 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 57 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O 11422 - UIC Ulster GAA ad.indd 1 10/01/2020 13:53 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas games. -

A History of the GAA from Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to Use This Pack Contents

Primary School Teachers Resource Pack A History of The GAA From Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to use this Pack Contents The GAA Museum is committed to creating a learning 1 The GAA Museum for Primary Schools environment and providing lifelong learning experiences which are meaningful, accessible, engaging and stimulating. 2 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – Teacher’s Notes The museum’s Education Department offers a range of learning 3 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – In the Classroom resources and activities which link directly to the Irish National Primary SESE History, SESE Geography, English, Visual Arts and 4 Seven Men in Thurles – Teacher’s Notes Physical Education Curricula. 5 Seven Men in Thurles – In the Classroom This resource pack is designed to help primary school teachers 6 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – plan an educational visit to the GAA Museum in Croke Park. The Teacher’s Notes pack includes information on the GAA Museum primary school education programme, along with ten different curriculum 7 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – linked GAA topics. Each topic includes teacher’s notes and In the Classroom classroom resources that have been chosen for its cross 8 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final curricular value. This resource pack contains everything you 1939 – Teacher’s Notes need to plan a successful, engaging and meaningful visit for your class to the GAA Museum. 9 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final 1939 – In the Classroom Teacher’s Notes 10 Famous Matches: New York Final 1947 – Teacher’s Notes provide background information on an Teacher’s Notes assortment of GAA topics which can be used when devising a lesson plan. -

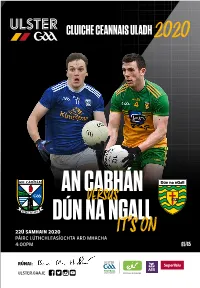

Ulster Final Programme

CLUICHE CEANNAIS ULADH2O2O AN CABHÁN DÚN NAVERSUS NGALL 22Ú SAMHAIN 2020 IT’S ON PÁIRC LÚTHCHLEASÍOCHTA ARD MHACHA 4:00PM £5/€5 RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE The stands may be silent but TODAY’S GAME we know our communities are CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 72 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From TODAY’S GAME CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU (SUBJECT TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ ATHLETICVERSUS GROUNDS, ARMAGH SUNDAY 22ND NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Maor Líne: Jerome Henry (Maigh Eo) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Maoir: Kevin Toner, Alan Nash, Tom O’Kane & Marty Donnelly CLÁR AN LAE: IF GAME GOES TO EXTRA TIME 15.20 Teamsheets given to Match Referee 1 7. 4 4 Toss & updated Teamsheets to Referee 15.38 An Cabhán amach ar an pháirc 17.45 Start of Extra Time 1st Half 15.41 Dún na nGall amach ar an pháirc 17.56* End of Extra Time 1st Half 15.45 Oifigigh an Chluiche amach ar an pháirc Teams Remain on the Pitch 15.52 Toss 17.58* Start of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.57 A Moment’s Silence 18.00* End of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.58 Amhrán na bhFiann 16.00 Tús an chluiche A water break will take place between IF STILL LEVEL, PHASE 2 (PENALTIES) the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 18:05 Players registered with the 16.38* Leath-am Referee & Toss An Cabhán to leave the field 18:07 Penalties immediately on half time whistle Dún na nGall to leave the field once An Cabhán have cleared the field 16.53* An dara leath A water break will take place between the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 17.35* Críoch an chluiche 38 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas programme. -

The Word “Legend”

True Legends are Gathering in Ballybofey… The word “Legend” is an often overused word in describing great sporting prowess or great GAA games and an official definition states “anyone or anything whose fame promises to be enduring”. The exploits of the youthful Clare Hurling team in winning the Liam McCarthy Cup on Saturday evening last, and in doing so beating a well fancied Cork side managed by the great Jimmy Barry Murphy, are already gaining legendary status. The fact that Cork only managed to lead both games for only 90 seconds is a testament to the Clare team but a word of warning….legends are not made in one sporting year !! The more mature readers will recall the fair haired Pat Spillane from the Templenoe Club in the Kingdom of Kerry, setting off on many a solo run from his own half back line and kicking score after score in All-Ireland Finals…I thought that he ran on the tips of his toes..!!!!…then again Legends can perform true feats of skill. True Legend…11 Munster Medals, 2 National Football Medals, 8 All-Ireland Medals and 9 All-Star Awards. Or Colm O Rourke gracefully weaving around flat-footed corner backs to score goals and points at ease, almost like a giant in slow motion. True Legend. 5 Leinster Medals, 3 National Football Legends, 2 All- Ireland Medals and 3 All-Star Awards. Peter Canavan struck fear into whole football teams when he got the ball within scoring distance and his deft touches when scoring goals would be the pride of any Premiership player on €150k a week. -

Reifreann an Daingin Gan Bhrí for the Irish Language and Irish Seolfar Lámhleabhar Traenála Ar an Medium Education

acmhainn eagna www.acmhainn.ie BOCHTANAS: “Ach bhí a fhios agam le fada 43 riamh - nó tá mo cheann sean - gur fíordheacair a bheith ionraic má tá tú róbhocht, agus gur mar an gcéanna ag an uchtach é. Is fearrde na suáilcí dúshraith de mhaoin an tsaoil a bheith fúthu.” – Seosamh Mac Grianna, Mo Bhealach Féin www.nuacht.com NUACHTÁN LAETHÚIL NA GAEILGE Cuardaigh nuathéarmaíocht na Gaeilge ar www.acmhainn.ie 9 771364 749027 Praghas molta miondíola LÁ: Iml 27 Uimh 207 Dé Máirt 24 Deireadh Fómhair 2006(Poblacht na hÉireann) 80c 80c / 50p LáGonta Beidh seimineár ar inimirce, imeascadh agus an Ghaeilge á reáchtáil ag an ghrúpa iMeasc ar 27 Deireadh Fómhair. A seminar on immigration, integration and Irish will take place in Dublin on 27 October. ➔ 3 ––––––––––––––––––––––––– Díríonn Méadhbh Ní hEadhra ar an gcontúirt go bhfuil íomhánna leictreonacha de pháistí á uaschóipeáil ar an idirlíon. Méadhbh Ní hEadhra isn’t convinced of the benefits of the internet - especially as pictures of children are being uploaded on dubious sites ➔ without their permission. 4 Mháirseáil lucht agóide Ros Muc ar son phobal Ros Dumhach Dé Domhnaigh agus iad ag léiriú tacaíochta ––––––––––––––––––––––––– Rosc Catha Ros Muc: dá gcairde i nGaeitacht Mhaigh Eo. Scéal iomlán agus tuilleadh pictiúr ar Lch 3 Díbhinn síochána do naíscoil Le Concubhar Ó Liatháin na ar an suíomh agus cúiteamh a fháil ar ndéanfadh siad infheistiú i naíscoil a Tá tuismitheoirí agus daltaí i an díshealbhú gan choinne a rinneadh. thógáil sa cheantar. Dónall Ó Conaill, gceantar na Carraige Báine -

Donegal GAA County Convention 2020

Comhdáil Blaintuil 2020 CLG Dhún Na nGall Donegal GAA County Convention 2020 Choiste Dhún na nGall CLG Comdháil Bhliantúil CLG Dhún nan Gall 2020 Clár an Leabhair 1. Glacadh le Buan-Orduithe 2 2. Miontuairiscí Chomhdháil Bhliantúil CLG Dhún na nGall 3 3. Tuarascáil an Rúnaí 2020 12 4. Tuarascáil an Chisteora & an Iniúchóra ar chuntaisí an Choiste Condae don bhliain dár críoch 31ú Meán Fómhair 2020 5. Tuarascáil Oifigeach Chultúrtha agus Teanga 2020 23 6. Tuarascail Runaí Coiste Cheannais na gComórtaisí 28 7. Tuarascáil an Oifigeach Chaidrimh Phoiblí 2020 32 8. Óráid an Chathaoirligh 9. Toghadh na nOifigeach don bhlain 2021 43 10. Tuarascail Oifigeach Forbartha 44 11. Tuarascáil Choiste Iománaíochta 50 12. Tuarascáil Oifigeach Oiliúna 52 13. Tuarascáil Choiste na Réiteoirí 57 14. Tuarascáil Rúnaí Choiste na hIar Bhunscoileanna 60 15. Tuarascáil Rúnaí Chumann na mBunscoil 62 16. Tuarscail Thoscaire Ard Chomhairle 68 17. Tuarascail Rúnaí an Choiste Éisteachta 70 18. Tuarscáil Comhairle Uladh (1) 71 19 Tuarscáil Comhairle Uladh (2) 72 20. Tuarscáil Leas-Chathaoirleach 74 21 Tuarscáil Leas-Chisteoir 75 22. Tuarascáil Choiste Folláine agus Sláinte 76 22. Tuarascáil Choiste Pleanáil Cluichí 80 23. Ballraíocht 82 1 Buan-orduithe don Chomhdhail Bhliantuil Standing Orders for Annual Convention 1. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment shall formally propose the resolution or amendment. 2. A resolution or amendment shall require a formal seconder in order to establish a live debate. 3. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak for five minutes but not more than five minutes. 4. A delegate speaking to a resolution or an amendment must not exceed three minutes.