Max Estenger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Max Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Peter Max Peter Max is a multi-dimensional creative artist. He has worked with oils, acrylics, water colors, finger paints, dyes, pastels, charcoal, pen, multi-colored pencils, etchings, engravings, animation cells, lithographs, serigraphs, silk screens, ceramics, sculpture, collage, video and computer graphics. He loves all media, including mass media as a "canvas" for his creative expression. As in his prolific creative output, Max is as passionate in his creative input. He loves to hear amazing facts about the universe and is as fascinated with numbers and mathematics as he is with visual phenomena. "If I didn't choose art, I would have become an astronomer," states Max, who became fascinated with astronomy while living in Israel, following a ten-year upbringing in Shanghai, China. "I became fascinated with the vast distances in space as well as the vast world within the atom," says Max. Peter's early childhood impressions had a profound influence on his psyche, weaving the fabric that was to become the tapestry of his full creative expression. It was a childhood filled with magic and adventure, an odyssey the likes of which few people have had, artists included. European born, Peter was raised in Shanghai, China, where he spent his first ten years. He lived in a pagoda-style house situated amidst a Buddhist monastery, a Sikh temple and a Viennese cafe. And yet, with all that richness and diversity of culture, he still had a dream of an adventure yet to come in a far-off land called America. -

Hottest Show On

SANGAM PAGE A3 WATER POLO PAGE B6 Indian eatery closes at J Street Colonials struggling as season closes THURSDAY The GW October 23, 2008 ALWAYS ONLINE: WWW.GWHATCHET.COM Vol. 105 • Iss. 20 Hatchet AN INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER - SERVING THE GW COMMUNITY SINCE 1904 Alumnus Unity Ball campaigns will cost for Senate $50,000 by Ian Jannetta Hatchet Staff Writer Event promotes More than 30 years after moving into a room in Thurston Hall, GW Greek life, diversity alumnus and former Virginia Gov. Mark Warner hopes to move into the Senate office buildings this January. by Sarah Scire Warner, a Democrat, is favored to Campus News Editor beat Republican Jim Gilmore in the November election for one of the Vir- A semiformal ball this Saturday de- ginia Senate seats and return to D.C. signed to celebrate diversity and Greek- The 53-year-old graduated from GW letter life on campus will cost more than in 1977 before attending Harvard Law $50,000, with at least $20,000 coming School. from student fee allocations, according “I have several fond memories to Student Association documents and from my years at GW,” Warner wrote event planners. in an e-mail to The Hatchet. “Most of The Unity Ball will be held at the them are social, rather than academic. Capital Hilton Hotel with the dual goal Like the parties we used to have in the of commemorating the 150th anniver- Thurston Hall dorm.” sary of Greek-letter life at GW and en- Warner, who served as the Virginia couraging multicultural groups and governor from 2002 to 2006, is ahead of other student organizations to interact. -

2006 Promax/Bda Conference Celebrates

2006 PROMAX/BDA CONFERENCE ENRICHES LINEUP WITH FOUR NEW INFLUENTIAL SPEAKERS “Hardball” Host Chris Matthews, “60 Minutes” and CBS News Correspondent Mike Wallace, “Ice Age: The Meltdown” Director Carlos Saldanha and Multi-Dimensional Creative Artist Peter Max Los Angeles, CA – May 9, 2006 – Promax/BDA has announced the addition of four new fascinating industry icons as speakers for its annual New York conference (June 20-22, 2006). Joining the 2006 roster will be host of MSNBC’s “Hardball with Chris Matthews,” Chris Matthews; “60 Minutes” and CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace; director of the current box-office hit “Ice Age: The Meltdown,” Carlos Saldanha, and famed multi- dimensional artist Peter Max. Each of these exceptional individuals will play a special role in furthering the associations’ charge to motivate, inspire and invigorate the creative juices of members. The four newly added speakers join the Promax/BDA’s previously announced keynotes, including author and social activist Dr. Maya Angelou; AOL Broadband's Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Kevin Conroy; Fox Television Stations' President of Station Operations Dennis Swanson; and CNN anchor Anderson Cooper. For a complete list of participants, as well as the 2006 Promax/BDA Conference agenda, visit www.promaxbda.tv. “At every Promax/BDA Conference, we look to secure speakers who are uniquely qualified to enlighten our members with their valuable insights," said Jim Chabin, Promax/BDA President and Chief Executive Officer, in making the announcement. “These four individuals—with their diverse, yet powerful credentials—will undoubtedly shed some invaluable wisdom at the podium.” This year’s Promax/BDA Conference will be held June 20-22 at the New York Marriott Marquis in Times Square and will include a profusion of stimulating seminars, workshops and hands-on demonstrations all designed to enlighten, empower and elevate the professional standings of its members. -

Vol. 21, No. 5 May 2017 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 21, No. 5 May 2017 You Can’t Buy It Living the Cycle of the Garden by Amy Goldstein-Rice is part of the exhibit UP/STATE, a selection of recent works by the twelve members of Southern Exposure. UP/STATE will be on view in the UPSTATE Gallery on Main, in Spartanburg, SC, from May 9 - June 30, 2017. See the article on Page 18. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - UPSTATE Gallery on Main - Amy Goldstein-Rice Page 3 - North Charleston Arts Festival Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 5 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art Page 4 - Editorial Commentary & North Charleston Arts Fest Page 6 - Peter Scala Page 6 - North Charleston Arts Fest cont. Page 7 - Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Helena Fox Fine Art, Spencer Art Galleries, Page 8 - North Charleston Arts Fest cont. & Charleston County Public Library The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary, McCallum-Halsey Studios, Corrigan Gallery, Page 9 - Charleston Artist Guild & Anglin Smith Fine Art Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery, City Gallery at Waterfront Park, City of North Page 10 - Anglin Smith Fine Art cont., Dog & Horse Fine Art & Portrait, Ella W. Richardson Fine Charleston Art Gallery, Redux Contemporary Art Center & Halsey Institute of Art, Piccolo Spoleto Crafts Shows, Meyer Vogl Gallery & Ann Long Fine Art Contemporary Art, and Gibbes Museum of Art Page 11 - Ann Long Fine Art cont., Corrigan Gallery & Ellis Nicholson Gallery Page 8 - Fabulon Art & Halsey-McCallum Studios Page 12 - Ellis Nicholson Gallery cont., 38th Piccolo Spoleto Outdoor Art Exhibition & Page 9 - Karen Burnette Garner & The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary The Quench Project by Robert Maniscalco Page 11 - Whimsy Joy by Roz & Call for Lowcountry Ceramic Artists Page 14 - The Quench Project by Robert Maniscalco cont. -

<<< Peter Max Lawrence >>>

Peter Max Lawrence [email protected] petermaxlawrence.com SOLO EXHIBITIONS Return of the Yeti, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 The Umpire Strikes Back, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 Beyond Say, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 October Surprise, Jernquist Studio, Brooklyn, NY 2016 In With The Old & Out With The New - New Lofts Art Gallery, Stockton, KS 2015 iNtheStudioAgain&Again&again, one2one, Lucas, KS 2014 Sell Out | Spikes, San Francisco, CA 2013 The Indelible Sulk | Mission: Comics & Art, San Francisco, CA 2013 Magickal Marvels: Ethos, Mythos, and Pathos | James C. Hormel LGBT Center - San Francisco Public Library 2012 The Ghost Show | Gallerí Klósett | Reykjavík, Iceland 2012 At War: Truong Tran & Peter Max Lawrence | SOMArts, San Francisco, CA 2012 Here Comes The Rain | Her Majesty's Secret Beekeeper, San Francisco CA 2011 Prey for Them | Little Bird, San Francisco CA 2011 The Paper Trail | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA 2010 The Sweet Stink of Stigma, Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2010 Midnight Moth & Bug Issue #1 vol.3, The Tiny Gallery | Big Think Studios, San Francisco CA 2009 The Innocent Culprit | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Addicted to Applause | Diego Rivera Gallery, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Contemporary Dilemmas for the Ancient Gods | Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2006 The Woman of Willendorf and Worldy other Wonders | The Austin Law Group, San Francisco, CA , 2006 Art Span, Open Studios, San Francisco, CA, 2006 Sacred Monsters | Leedy-Voulkos -

Seville-Expo-1992.Pdf

t I t?t'\ FINAL REPORT UNITED STATES PAVILION SEVILLE EXPO'92 Table of Contents Summary Background and Pre-Opening Chronology The Pavilion and Exhibition Corporate Participation Defense Department Pavilion Operations Cultural Programs Sports Programs Special Events 10 SpecialVisitors 13 Conclusion 14 Appendices 15 Project Summary Pavilion: Two 10,000 square feet geodesic domes, 20,000 squarel feet exhibit hall/office building, 3,000 square foot demonstration home , 12,000 square foot outdoor sports and performance stage courtyard complex, 35,000 square feet of outdoor exhibits and landscaping. Gomponents: Bill of Rights Exhibit, World Song Theater, Sports and Cultural Performance Court, American Spirit Home, GM Auto Exhibit, Kansas City Exhibit, Peter Max Murals, Sprint Exhibit, Ameritech Exhibit, U.S. Mint Exhibit, DHL Exhibit, All American Sport Shop, Yankee Stadium Restaurant, and Baskin Robins lce Cream Stand. Pavilion Attendance: 2,400,000 Gultural Programs: Number of participants: Sports: 1,000 Performing Arts: 3,500 Funding: Cash: Federal $20.626.000 Private $4.972.248 lnkind: Private $11.314.758 Background and Pre-Opening Chronology Background Seville Expo '92 commemorated the 500th anniversary of Columbus' voyage to the New World and picked the theme "Age of Discovery." lt opening April 20, 1992 and closed Columbus Day, October 12, 1992. Attendance was over 40 million. Spain invested over $4 billion in the expo and related infrastructure, the largest such investment in world's fair history. 110 countries participated on the 530 acre site located on an island in the Guadalquivir river across from central Seville. At the time Seville Expo'92 was proposed, the Bureau of International Expositions, the organization that sanctions such events, had two categories for world's fairs: universal and specialized. -

Presidential Files; Folder: 9/30/80; Container 178

9/30/80 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 9/30/80; Container 178 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL.,, LIBRARIES) 0 I) C.l ,, 0 ' FORM OF r: DOCUMENT CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION I ,, emo w/att. P!OI!I !3Lzez±nsk± to The l'Leisident (2pp ) re· 9/29./80 A ,, Ellsworth Baftker Mjssjo:R to J;Rdja fie_ tJI...C- I:46-2..1--· J/- I- 2 t/J..!/If- r·ot fCr /{ " " ' I ' '' ' " >' " ,, " 6 " . ' . FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Offices, Office of the Stat� See.-Pres. Hand writing File 9/Y/80 BOX 208 RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. � (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the onor's deed of gift. '' �·-·--�·---��--�--�---------------.--.....--..;1;_-�--:...;....�...-....=�· ' ';\ . NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 14,29 (6-85) " .����� •co -�\:;�;��" �� 0 ' "'�,'\'··', '' .."' ' ; f-.· 0 � i '· .. '( . ' 0. .• THE WHITE HO�SE WASHINGTON 9/30/80 ·' Joyce Cook kw hat({ v1 C cu& t \• Thanks Susan Clough .·. .:;�-\� ; . ' '.,. {. ? 0 . · .. ' b & 0 0 0 ' � - . :\ �· � � � � r,! J � ·' ' ,, ,. :� ' J '' ' I ··.'•. )tti� . :� CA'j' DR.IIENRY L. BUCKARDT l'rc!idcnt PAEONIAN SPRINGS, TELEPHONE VIRGINIA 22129 703-338-6290 Hr. President ' . 1.-le are promoting the use of �;' .. ·" work horses on small farms �0 ,'<;...., �'"' to save energy. '· ;� � .,;"' .;··,· �· � A l�tter of suP,port �wul b b ·- er •. 'J 'q,,, v y helpful ;'��-:�¥ -� � ...-Y'" -P rD...1- ,_ ··. ·> - ,� 0" - "' ye,v-v-.1-f). -

A Conversation with Peter Max By: Gina Samarotto

www.private-air-mag.com 1 ARTS & COLLECTIBLES ACHIEVING MAX-IMUM EFFECT A Conversation with Peter Max By: Gina Samarotto www.private-air-mag.com 49 © Peter Max 2014 ARTS & COLLECTIBLES © Peter Max 2014 eter Max, sporting a pair of red sneakers paired Born in the late 1930’s to a businessman father with a with polka dotted socks and a smile that reaches penchant for art and a fashion designer mother, Max’s all the way to his twinkling eyes, warmly welcomes early years were spent growing up in Shanghai. It was Pme into his upper west side studio. With a handshake there, in a pagoda house standing in the shadows of a that ends in a hug and an invitation to sit down for some neighboring Buddhist temple, that a passion for drawing tea and a slice of chocolate cake, it’s easy for a feeting and painting took hold of the burgeoning artist. Yet moment at least, to forget that the utterly charming man despite the impressive, raw talent that surfaced when standing before me is arguably the most recognizable, Max frst put pencil to paper, it was the stars above that successful artist of our time. teased the imagination of the curious, demiurgic little boy. “What I really wanted to be was an astronomer,” Max With nearly every square inch of the space flled to says when asked about those early years. “I loved – and I overfowing with everything from family photos to a still love – everything that space and the cosmos and all prized collection of cookie jars to a life sized, cosmic cow; the universes have to ofer. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

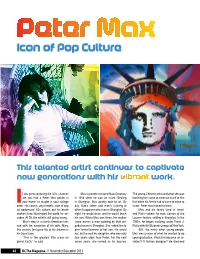

Peter Max Icon of Pop Culture

Peter Max Icon of Pop Culture This talented artist continues to captivate new generations with his vibrant work. f you grew up during the ’60s, chances Max’s parents escaped Nazi Germany The young Chinese artist and what she was are you had a Peter Max poster in in 1938 when he was an infant. Settling teaching him came to mean so much to him I your home, or maybe in your college in Shanghai, Max quickly took to art. By that when his family had to leave to move to dorm. His cosmic, psychedelic style of pop day, Max’s father sold men’s clothing to Israel, Peter was moved to tears. art epitomized ’60s culture, but his brush other Europeans who lived in Shanghai. By Max and his family lived in Israel, strokes have illuminated the world for de- night, he would draw, and he would teach and Paris—where he took classes at the cades. At 76, the artist is still going strong. his son. When Max was three, his mother Louvre—before settling in Brooklyn. In the Max’s story is a classic American tale, came across a man painting by their pa- 1950s, he began studying under Frank J. and with the exception of his wife, Mary, goda house in Shanghai. She asked him to Reilly at the Art Students League of New York. this country that gave life to his dreams is give formal lessons to her son. He would Still, like many other young people, his truest love. not, but he sent his daughter, who was only Max was unsure of what he wanted to do “This is the greatest little place on four years older than Peter. -

GCCA Honors Thomas Cole's Hudson

ALBANY, NY PERMIT #486 Published by the Greene County Council on the Arts 398 Main Street, Catskill, NY 12414 • Issue 123 • July /August 2018 GCCA Honors Thomas Cole’s Hudson River School in “New School” overtly or abstractly. The words in Fern Apfel’s “The River” series are taken from a diary published in 1928 that documents the days as they pass, starting from New Year’s Day and traveling chronologically through the year through the three pictures. The year ends and begins, mimicking the river’s enduring spirit and constant motion. Several of the artists in New School not only take their School group exhibition will be on display through August 4, 2018, inspiration from the outdoors, but also make their art outdoors, concurrently with “Repeated Returning,” a solo show in GCCA’s a process called plein air that was common to the Hudson River upstairs gallery of multidisciplinary artist, Caitlin Parker. Parker’s School of artists. Marianne Tully chooses to do plein air landscape work involves printing on paper and fabric with pressed plants and paintings because she wishes “to capture the tones and forms experimentation with natural dyes, cyanotype process on fabric, of nature in my paintings, giving the viewer some of the same sewing and weaving. experience that I have felt in confronting the exquisite beauty The Greene County Council on the Arts Gallery is located at 398 Main Street, Catskill,bNY.bGallery hours are Monday through In honor of the 200th anniversary of Thomas Cole’s fi rst and reality of the earth.” Sheila Trautman, a plein air watercolorist, tries to “communicate the fundamental nature of the scenes she Friday from 10:00 a.m. -

L O T H a R O S T E R B U

L O T H A R O S T E R B U R G FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS AND RESIDENCIES 2018 Jordan Schnitzer Award for Excellence in Printmaking 2013 Navigation Press, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, Artists Residency. Cill Rialaig Art Center, Artists Residency in County Kerry, Ireland. 2011 Bogliasco Foundation, Artist residency at the Liguria Studies Center, Italy. 2010 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship. Academy Award in Art; from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York. Bard College research grant Electronic Music Foundation & Meet the Composer's Commissioning Music/USA, Collaborative grant with Elizabeth Brown for “A Bookmobile for Dreamers” 2009 AEV Foundation Grant, New York. New York Foundations for the Arts Fellowship for Printmaking/Drawing/Artist’s Books. 2005 and’06 Hui N’Eau Arts Center, Artist in Residence. Makawao, Maui, HI 2004 Concordia Career Advancement Grant (awarded through NYFA). 2003 New York Foundations for the Arts Fellowship for Printmaking/Drawing/Artist’s Books. 1996-97-02 MacDowell Colony, Artist in Residence. Peterborough, NH. 1999 Virginia Center of the Creative Arts, Artist in Residence. Sweet Briar, Virginia. 1998 Bogliasco Foundation, Artist residency at the Liguria Studies Center, Italy. 1987 Internationale Senefelder Stiftung, Traveling show of the Ten Best. 1986 8. Internationale Graphiktriennale, 6th Prize. Frechen, Germany. SOLO SHOWS 2018 Lesley Heller Gallery, “Waterline”. New York, NY. 2017 Ester Massry Gallery, College of Saint Rose, “Reaching for the Sky”, Albany NY. 2015 Lesley Heller Workspace, “Babel”. New York, NY. Gottheimer Fine Art, “From the Piranesi Project”, St Louis, MO. 2014 Pulse Art Fair, “Piranesi” Lesley Heller Workspace, Miami Beach, FL.