And Gentrification: a Case of Quezon City, the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY National Ecology Center, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Phone Nos

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY National Ecology Center, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Phone Nos. (02) 8 376-4039, (02) 8 376-4072, (02) 8 376-4044, (02) 8 332-2353, (02) 8 332-2341, (02) 8 376-5430 Locals 115, 116, 117 and look for Ms. Julie Ann G. Blanquisco or Ms. Marivic A. Dela Torre-Santos E-mail: [email protected] | [email protected] Website: http://llda.gov.ph List of APPROVED DISCHARGE PERMITS as of September 03, 2021 Establishment Address Permit No. Approve Date 11 FTC Enterprises, Inc. 236 P. Dela Cruz San Bartolome Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03532 August 18, 2021 189 Realty Corp. (CI Market) Qurino Highway Santa Monica, Novaliches Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03744 August 20, 2021 189 Realty Corporation - 2nd (CI Market/Commercial Complex) Quirino Highway, Sta. Monica Novaliches Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03743 August 20, 2021 21st Century Mouldings Corporation 18 F. Carlos St. cor. Howmart Road Apolonio Samson Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03541 August 23, 2021 24K Property Ventures, Inc. (20 Lansbergh Place Condominium) 170 T. Morato Ave. cor. Sct. Castor Sacred Heart Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-02819 July 15, 2021 3J Foods Corp. Sta. Ana San Pablo City Laguna DP-16d-2021-03174 August 06, 2021 8 Gilmore Place Condominium 8 Gilmore Ave. cor. 1st St. Valencia New Manila Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03829 August 27, 2021 AC Technical Services, Inc. 5 RMT Ind`l. Complex Tunasan Muntinlupa City MM DP-23a-2021-01804 May 12, 2021 Ace Roller Manufacturing, Inc. -

History of Quezon City Public Library

HISTORY OF QUEZON CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY The Quezon City Public Library started as a small unit, a joint venture of the National Library and Quezon City government during the incumbency of the late Mayor Ponciano Bernardo and the first City Superintendent of Libraries, Atty. Felicidad Peralta by virtue of Public Law No. 1935 which provided for the “consolidation of all libraries belonging to any branch of the Philippine Government for the creation of the Philippine Library”, and for the maintenance of the same. Mayor Ponciano Bernardo 1946-1949 June 19, 1949, Republic Act No. 411 otherwise known as the Municipal Libraries Law, authored by then Senator Geronimo T. Pecson, which is an act to “provide for the establishment, operation and Maintenance of Municipal Libraries throughout the Philippines” was approved. Mrs. Felicidad A. Peralta 1948-1978 First City Librarian Side by side with the physical and economic development of Quezon City officials particularly the late Mayor Bernardo envisioned the needs of the people. Realizing that the achievements of the goals of a democratic society depends greatly on enlightened and educated citizenry, the Quezon City Public Library, was formally organized and was inaugurated on August 16, 1948, with Aurora Quezon, as a guest of Honor and who cut the ceremonial ribbon. The Library started with 4, 000 volumes of books donated by the National Library, with only four employees to serve the public. The library was housed next to the Post Office in a one-storey building near of the old City Hall in Edsa. Even at the start, this unit depended on the civic spirited members of the community who donated books, bookshelves and other reading material. -

Company Name: Ayala Land Malls Inc. Corporate Address: 5Th Floor, Glorietta 4, Ayala Center Makati City

Company Name: Ayala Land Malls Inc. Corporate Address: 5th Floor, Glorietta 4, Ayala Center Makati City Mall List Luzon Mall Name Mall Location Harbor Point Subic Bay Freeport Zone, Zambales MarQuee Mall Angeles City, Pamapanga Ayala Malls Cloverleaf A Bonifacio Ave Brgy Balingasa, Quezon City TriNoma Edsa Corner North Avenue, Quezon City Ayala Malls Vertis North North Avenue Brgy Bagong Pag-asa, Quezon City Fairview Terraces Quirino Highway cor Maligaya Drive Novaliches, Quezon City U.P. Town Center Katipunan Avenue Diliman, Quezon City Ayala Malls Feliz Amang Rodriguez Cor J.P. Rizal Brgy Dela Paz, Pasig City Ayala Malls Marikina Liwasag Kalayaan Brgy Marikina Heights, Marikina City Ayala Malls The 30th Meralco Ave. Brgy Ugong, Pasig City Market! Market! Bonifacio Global City, Taguig One Ayala Ave Ayala Avenue, Makati City Glorietta Ayala Center, Makati City Greenbelt Legazpi Street, Makati City Ayala Malls Circuit Circuit Makati, Hippodromo, Carmona, Makati City Ayala Malls Manila Bay Macapagal Blvd cor. Aseana Avenue, Paranaque City Alabang Town Center Alabang Town Center, Muntinlupa City The District Dasma Molina Road, Dasmarinas, Cavite The District Imus Aguinaldo Highway cor. Daang Hari Road Anabu II-D, Imus, Cavite Vermosa Daang Hari Road cor. Vermosa Blvd., Imus, Cavite Ayala Malls Solenad Nuvali, Brgy. Sto. Domingo, City of Santa Rosa, Laguna Ayala Malls Serin Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo Highway Tagaytay City, Cavite Ayala Malls Legazpi Rizal Street corner Quezon Ave., Barangay Capantawan, Legazpi City, Albay Mall List VisMin Mall Name Mall Location Abreeza J.P. Laurel Ave., Davao City Ayala Center Cebu Cebu Business Park, Cebu City Central Bloc I. Villa Street Cebu IT Park, Cebu City Centrio Mall CM Recto-Corrales Ave, Cagayan de Oro Ayala Malls Capitol Central Gatuslao Street, Bacolod City . -

Clement Castigador Camposano, Ph.D

UPD_EDUC_EDFD_CV_CCamposano Clement Castigador Camposano, Ph.D. Profile Clem Camposano earned his Ph D. in Philippine Studies (Anthropology) from the Tri-College Program of the University of the Philippines - Diliman in 2009. He holds an M.A. in Political Science from U.P Diliman (1992) and a B.A. in Political Science and History (double major) from U.P. Visayas (1986). His current research interest is in the anthropology of contemporary migration, anthropology of education, Philippine history and culture, as well as citizenship and civic education. He has published articles in scholarly and peer-reviewed journals and has consistently presented academic papers in both local and international conferences. He is the current President of the Philippine Studies Association (PSA) and served in the board of the Anthropological Association of the Philippines/Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao (UGAT) until 2016. As a practicing ethnographer, he actively works with the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC) in providing trainings in qualitative research methods to the academic staff of various educational institutions. He also sits in the Editorial Advisory Board of Filipinas: Journal of the Philippine Studies Association, Inc. Dr. Camposano has had a long academic career, serving various institutions in different capacities. He is presently a faculty member at the Division of Curriculum and Instruction – Educational Foundations, College of Education, University of the Philippines Diliman where he teaches courses in the anthropology and sociology of education. Prior to joining U.P. Diliman in 2017, he was a faculty member at the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) where he taught courses in Philippine history and culture, Southeast Asian history, social science research, political theory and political dynamics. -

The Ateneo De Manila University Sustainability Report for School Year 2012 - 2014 Contents GRI Report Profile

ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY SUSTAINABILITY REPORT JULY 2014 The Ateneo de Manila University Sustainability Report for School Year 2012 - 2014 Contents GRI Report Profile Strategic Thrust of Ateneo de Manila University 2011-2016 Reporting Period April 2012 – March 2014 Statement from the President Introduction to the Report Date of Most Recent Previous Report - Reporting Cycle Biennial The Ateneo de Manila University 10 Contact Point Ma. Assunta C. Cuyegkeng, Ph.D. History Population Director Vision and Mision Entities Ateneo Institute of Sustainability Ethics and Integrity Centers and Units [email protected] The Ateneo Community Stakeholder Engagement The Campuses Surveys In Accordance Option Core, not externally assured International Linkages University Activities and University Linkages Operations Stakeholders What Matters to Us The Ateneo Sustainability Report 2014 was prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 Guidelines. Economic Impacts 27 Economic Performance Indirect Economic Impacts Credits Environmental Impact Writers Contributors Layout Artist 33 Energy Effluents and Waste Assunta Cuyegkeng Jon Bilog Earl Juanico Aaron Corpuz Biodiversity Materials Abigail Favis Enrico Bunyi Carlie Labaria Social Impact Kendra Gotangco Katrina Cabanos Anna Mendiola 43 Marion Tan Trinket Canlas-Constantino Roi Victor Pascua Employment Local Communities Labor/Management Relations Rachel Consunji Carissa Quintana Andreas Dorner Jervy Robles Index 53 Zachery Feinberg Chuck Tibayan Sustainability Policies About the Ateneo Institue of Hendrick Freitag Aaron Vicencio Acknowledgements Sustainability Additional Photo Credits: Reuben L. Justo, http://reubenjusto.tripod.com (Old Manila Observatory) Manila Observatory Website, http://www.observatory.ph (Father Federico Faura, SJ) Aegis 2014 The heart of sustainability lives ‘‘ in the people, who choose to be ‘‘ responsible for themselves and the greater society, for the present and the future. -

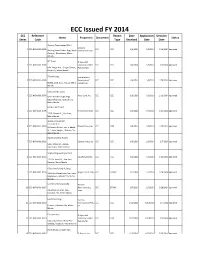

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date Alabang Town Center BPO 1 Alabang 1 ECC-NCR-1401-0001 ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Alabang Town Center, Brgy. Ayala, Commercial Corp. Alabang,, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila IBP Tower Ortigas and 2 ECC-NCR-1401-0003 Company Limited ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/6/2014 Approved Julia Vargas Ave., Ortigas Center,, Partnershipp Pasig City, Metro Manila T-Park Project Fort Bonifacio 3 ECC-NCR-1401-0005 Development ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/28/2014 Approved B18,L4, 26th, BGC,, Taguig, Metro Corporation Manila Vertis North Towers 4 ECC-NCR-1401-0006 Ayala Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Vertis North Triangle, Brgy. Bagong Pag-asa,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Fortune Hill Project 5 ECC-NCR-1401-0008 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 173 P. Gomez St.,, San Juan, Metro Manila Studio A Residential Condominium 6 ECC-NCR-1401-0009 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEER 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 99 Xavierville Ave., cor. E. Abada St., Loyola Heights,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Plastic Recycling Project 7 ECC-NCR-1401-0011 Sanplas Industries ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/7/2014 Approved 6390 Tatalon St., Ugong,, Valenzuela, Metro Manila Shipbuilding and Repair Yard 8 ECC-NCR-1401-0013 Sas Shipyard, Inc. -

AGIGIS-2010.Pdf

GENERAL INFORMATION SHEET (GIS) FOR THE YEAR 2010 STOCK CORPORATION GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: 1. FOR USER CORPORATION: THIS GIS SHOULD BE SUBMITTED WITHIN THIRTY (30) CALENDAR DAYS FROM THE DATE OF THE ANNUAL STOCKHOLDERS' MEETING. DO NOT LEAVE ANY ITEM BLANK. WRITE "N.A." IF THE INFORMATION REQUIRED IS NOT APPLICABLE TO THE CORPORATION OR "NONE" IF THE INFORMATION IS NON-EXISTENT. 2. IF NO MEETING IS HELD, THE CORPORATION SHALL SUBMIT THE GIS TOGETHER WITH AN AFFIDAVIT OF NON-HOLDING OF MEETING WITHIN THIRTY (30) CALENDAR DAYS FROM THE DATE OF THE SCHEDULED ANNUAL MEETING (AS PROVIDED IN THE BY-LAWS). HOWEVER, SHOULD AN ANNUAL STOCKHOLDERS' MEETING BE HELD THEREAFTER, A NEW GIS SHALL BE SUBMITTED/FILED. 3. THIS GIS SHALL BE ACCOMPLISHED IN ENGLISH AND CERTIFIED AND SWORN TO BY THE CORPORATE SECRETARY OF THE CORPORATION. 4. THE SEC SHOULD BE TIMELY APPRISED OF RELEVANT CHANGES IN THE SUBMITTED INFORMATION AS THEY ARISE. FOR CHANGES RESULTING FROM ACTIONS THAT AROSE BETWEEN THE ANNUAL MEETINGS, THE CORPORATION SHALL SUBMIT ONLY THE AFFECTED PAGE OF THE GIS THAT RELATES TO THE NEW INFORMATION TOGETHER WITH A COVER LETTER SIGNED BY THE CORPORATE SECRETARY OF THE CORPORATION. THE PAGE OF THE GIS AND COVER LETTER SHALL BE SUBMITTED WITHIN SEVEN (7) DAYS AFTER SUCH CHANGE OCCURRED OR BECAME EFFECTIVE. 5. SUBMIT TWO (2) COPIES OF THE GIS TO THE CENTRAL RECEIVING SECTION, GROUND FLOOR, SEC BLDG., EDSA, MANDALUYONG CITY. ALL COPIES SHALL UNIFORMLY BE ON A4 OR LETTER-SIZED PAPER WITH A STANDARD COVER PAGE. THE PAGES OF ALL COPIES SHALL USE ONLY ONE SIDE. -

Bonchon Store List

Bonchon Store List RCBC Bankard-JCB Spend Anywhere Store Name Store Address SM MEGAMALL Unit 159-A, Bldg. A, Upper Ground Floor, SM Megamall, Mandaluyong City ROBINSONS GALLERIA Ground Floor, Food Court, Robinsons Galleria, Ortigas, Pasig City GREENHILLS PROMENADE Unit FC 4, Lower Level, Greenhills Promenade, GSC, Ortigas Avenue, San Juan City KATIPUNAN 2F Regis Center, 327 Katipunan Avenue, Quezon City SHANGRI-LA PLAZA Unit 48 Lower Ground Floor Level, Shangrila Plaza Mall, Edsa Shaw Boulevard, Mandaluyong City UNIVERSITY MALL TAFT Ground Floor University Mall, 2507 Taft Avenue, Malate, Manila TOMAS MORATO 2nd Floor Il Terrazo, Tomas Morato corner Scout Madrinan, Quezon City TRINOMA Level 1 Trinoma, Quezon City SM MALL OF ASIA G/F Space 100-101, SM Mall of Asia, Diokno Boulevard, Pasay City ALABANG TOWN CENTER Space 1011 Lower Ground Floor, New Wing, The Garden, Alabang Town Center, Alabang, Muntinlupa City GREENBELT Ground Floor, Greenbelt 1, Ayala Center, Paseo de Roxas, Brgy. San Lorenzo, Makati City AYALA TRIANGLE GARDEN Ground Floor Space 4, Ayala Triangle Gardens, Paseo de Roxas corner Makati Avenue, Makati Cty LUCKY CHINATOWN 3rd Floor Lucky Chinatown Mall, Reina Regente corner Dela Reina Sts., Brgy. 293, Zone 28, Binondo, Manila SM TAYTAY GF Building A, SM City Taytay, Manila East Road, Brgy. Dolores, Taytay, Rizal SM NORTH EDSA ANNEX 3/F SM North Edsa, The Annex, Quezon City HIGH STREET THE FORT Ground Level, 7th Avenue corner 28th St., One Parkade Building, Bonifacio High Street, Taguig City SM FAIRVIEW 2/F Main Building, Quirino Avenue corner Regalado St., Greater Lagro, Quezon City SM MANILA 4/F Unit 418, SM Manila, Concepcion corner Arroceros and San Marcelino Streets, Manila ROBINSONS MANILA 4/F Center Atrium, Robinsons Place Ermita, Manila EASTWOOD Unit H2A, Eastwood City Walk 1, Eastwood City, Libis, Quezon City SM DAVAO G/F The Annex, SM City Davao, Quimpo Blvd., Tulip Drive, Ecoland Subdivision Matina, Davao City UP TECHNOHUB 2/F Space No. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

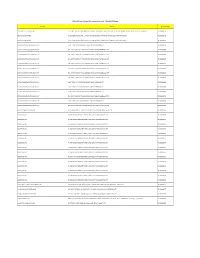

DOLE-NCR for Release AEP Transactions As of 7-16-2020 12.05Pm

DOLE-NCR For Release AEP Transactions as of 7-16-2020 12.05pm Company Address Transaction No. 3M SERVICE CENTER APAC, INC. 17TH, 18TH, 19TH FLOORS, BONIFACIO STOPOVER CORPORATE CENTER, 31ST STREET COR., 2ND AVENUE, BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY, TAGUIG CITY TNCR20000756 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000178 3O BPO INCORPORATED 2/F LCS BLDG SOUTH SUPER HIGHWAY, SAN ANDRES COR DIAMANTE ST, 087 BGY 803, SANTA ANA, MANILA TNCR20000283 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000536 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000554 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000569 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000607 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000617 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000632 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000633 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5TH-10TH/F TOWER 3, PITX #1, KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000638 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY ROAD, TAMBO, PARAÑAQUE CITY TNCR20000680 8 STONE BUSINESS OUTSOURCING OPC 5-10/F TOWER 1, PITX KENNEDY -

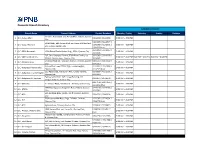

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP.