THE SILVER BULLET Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disneyland® Hotel Is Not Only an Icon, It Has Also Served As a Source of Inspiration to Visitors for Nearly Half a Century

Could there be a more inspirational setting than where it all began? The Disneyland® Hotel is not only an icon, it has also served as a source of inspiration to visitors for nearly half a century. In every aspect of the hotel, you’ll feel a sense of rich Disney history that makes this incredibly creative atmosphere truly legendary. From our state-of-the-art meeting facilities to our beautifully appointed rooms and suites, you will feel inspired. The spark of imagination — where does for the award-winning animated movies of the Walt it come from? For the Disneyland® Disney company. He hand selected this group to visualize, Resort, that spark is ignited by the design and build Disneyland® park. Today, the Imagineers Imagineers. Over 50 years ago, when Walt Disney was are responsible for every Disney theme park throughout planning the theme park of his dreams, he turned to the the world. But we will always remember that it all started most creative people he knew — the artists responsible in an orange grove in Southern California. www.disneylandmeetings.com 1 How can innovation come to life? Where will new ideas be generated? When does creativity become reality? At the Disneyland® Resort, we believe that inspiration can strike at any time. And where you begin your day is just as important as where you end it. That is why our hotels were designed to not only be warm and welcoming, but also to be the most creative, innovative and inspiring settings they can be. When you stay at any one of our hotels, nothing will get in the way of your creativity. -

City of Palm Springs Citywide Historic Context Statement & Survey Findings

282 THEME: POST-WORLD WAR II MULTI-FAMILY RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (1945-1969) Overview This theme explores the design and construction of mid-20th century multi-family residences in Palm Springs, from the immediate postwar period through 1969. While the emphasis in residential construction in Palm Springs following the war was decidedly in favor of single- family homes, a number of apartment buildings were constructed in the immediate postwar period. Apartments were typically found on Palm Canyon Drive, Indian Canyon Drive, Arenas Road, and Tamarisk Road. Significant architects and designers associated with multi-family residential development from this period include Clark & Frey, A. Quincy Jones, Wexler & Harrison, William Krisel, Paul Thoryk, Hai Tan, H.W. Burns, and many others. Developers include Rossmoor Corporation, Phillip Short and Associates, William Bone, and Jack and Richard Weiss. As a result of increased demand for housing, post-World War II multi-family residential development in Palm Springs took a variety of forms including garden apartments, large low-rise multi-building communities (including early condominium projects), split-level attached townhomes, and attached and semi-attached residences in clusters as small as two and as many as eight. In virtually every configuration, the focus of the design was around the pool (or pools as the scale of the developments increased). A rare example of wartime multi-family housing in Palm Springs is Bel Vista (1945-47, Clark & Frey). Throughout the country, wartime housing projects were invariably the only building projects not stalled by the onset of World War II. Bordered by E. Chia Road on the north, Sunrise Way on the east, Tachevah Drive on the south, and N. -

Copyright by Avi Santo 2006

Copyright by Avi Santo 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Avi Dan Santo Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Transmedia Brand Licensing Prior to Conglomeration: George Trendle and the Lone Ranger and Green Hornet Brands, 1933-1966 Committee: ______________________________ Thomas Schatz, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Michael Kackman, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Mary Kearney ______________________________ Janet Staiger ______________________________ John Downing Transmedia Brand Licensing Prior to Conglomeration: George Trendle and the Lone Ranger and Green Hornet Brands, 1933-1966 by Avi Dan Santo, B.F.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 Acknowledgements The support I have received from family, friends, colleagues and strangers while writing this dissertation has been wonderful and inspiring. Particular thanks go out to my dissertation group -- Kyle Barnett, Christopher Lucas, Afsheen Nomai, Allison Perlman, and Jennifer Petersen – who read many early drafts of this project and always offered constructive feedback and enthusiastic encouragement. I would also like to thank Hector Amaya, Mary Beltran, Geoff Betts, Marnie Binfield, Alexis Carreiro, Marian Clarke, Caroline Frick, Hollis Griffin, Karen Gustafson, Sharon Shahaf, Yaron Shemer, and David Uskovich for their generosity of time and patience in reading drafts and listening to my concerns without ever making these feel like impositions. A special thank you to Joan Miller, who made this past year more than bearable and brought tremendous joy and calm into my life. Without you, this project would have been a far more painful experience and my life a lot less pleasurable. -

Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8f76dbp No online items Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather Papers Susan Jones and Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/ © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather CSLA-23 1 Papers Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather Papers Collection number: CSLA-23 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Susan Jones and Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2003 Encoded by: Clay Stalls and Bri Wong © 2013 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather papers Dates: 1890-1990 Collection number: CSLA-23 Creator: Wrather, Jack, 1918-1984 Creator: Wrather, Bonita Granville, 1923-1988 Collection Size: 105 archival document boxes, 15 oversize boxes, 6 records storage boxes, 3 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: The Jack and Bonita Granville Wrather Papers consist of textual and non-textual materials dating from the period 1890 to 1990. They document the considerable careers of Jack (1918-1984) and Bonita Granville Wrather (1923-1988) in the areas of entertainment, business, and politics. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Publication Rights Materials in the Department of Archives and Special Collections may be subject to copyright. -

THE TATTLER Treemont Retirement Community, 2501 Westerland Drive, Houston, Texas 77063 / 713-783-6820

January 2015 THE TATTLER Treemont Retirement Community, 2501 Westerland Drive, Houston, Texas 77063 / 713-783-6820 A Whole Year of New Years Celebrating Many people around the globe will be counting down the seconds until January 1 to shout, “Happy New January Year!” But there are also many people who won’t be celebrating a new year on January 1. Some cultures do not even consider it to be the year 2015! Adopt a Rescued Bird Month For many Chinese, the New Year festival is the most important of the year. February 19 marks the beginning Mentoring Month of the year of the sheep, considered an unlucky year, for those born as sheep are said to be meek. International Creativity Month New Year’s in Thailand, known as Songkran, is celebrated over three days from April 13–15. The Thai Universal Letter Writing people take the notion of spring cleaning seriously, and they celebrate their New Year each spring with a Week festival of throwing water. Coincidentally, April is also January 8–14 the hottest month in Thailand, so thousands of people drenching each other with water in the streets provides Vocation Awareness Week the perfect means of escape from the scorching heat January 13–19 and suffocating humidity. Buffet Day It is tradition amongst both Ethiopians and Jewish January 2 people to celebrate their New Year in September. Enkutatash in Ethiopia falls on September 11, marking Twelfth Night the end of the rainy season and commemorating the return of the Queen of Sheba to Ethiopia after her visit January 5 to King Solomon in Jerusalem in 980 BC. -

MORNING BRIEFING March 25, 2020

MORNING BRIEFING March 25, 2020 Searching for Silver Bullets Check out the accompanying chart collection. (1) The Lone Ranger. (2) A horse named “Silver” and a gun full of silver bullets. (3) Cure worse than the disease? Social distancing crushing global economy. (4) Make millions of masks, and make us wear them when we go out of the house. (5) Eight other steps to free us from house arrest. (6) We disagree with the CDC’s case against surgical masks. (7) Don’t fight the Fed. (8) China’s economy may be recovering, but their overseas customers are falling into a severe recession. (9) Good news: Busts are followed by booms. (10) Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team’s report may be too alarmist. Editorial: Who Is That Masked Man? One of my favorite television shows when I was a kid growing up in Cleveland, Ohio was “The Lone Ranger.” It aired on the ABC television network from 1949 to 1957, with Clayton Moore in the starring role. Jay Silverheels, a member of the Mohawk Aboriginal people in Canada, played the Lone Ranger’s Indian companion Tonto. The fictional story line maintains that a patrol of six Texas Rangers is massacred, with a sole member surviving. The “lone” survivor disguises himself with a black mask and travels with Tonto throughout the West to assist those challenged by outlaws. The Lone Ranger rides a horse named “Silver” and uses silver bullets. At the end of most episodes, after the Lone Ranger and Tonto leave, someone asks the sheriff, “Who was that masked man?” The sheriff responds that it was the Lone Ranger, who is then heard yelling “Hi-yo, Silver, away!” as he and Tonto ride away on their horses. -

DKA-02-23-1966.Pdf

Mr. Bernard R. Kantor Department of Cinema University of Southern California University Park Los Angeles, California 90007 .JAMES STEWART 9 2 01 WILSHIRE: BOULEVARD BEVERLY HILLS, C AL I FORNI A December 8, 1966 Mr. Bernard R. Kantor Department of Cinema University of Southern California University Park Los Angeles, California 90007 Dear Mr. Kantor: I would like very much to attend the banquet planned by the Cinema Department on January 15, 1967 and appear on the panel for Frank Capra. I am just starting a picture but I am quite sure that our location work will be finished before January 15th. Sincerely, lm .., JAMES STEWART -=--~ - 9201 WILSHIRE BOULEVARD___. BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA - . --~ Delta Kappa Alpha National Honorary Cinema Fraternity HONORARY AWARDS BANQUET honoring Lucille Ball Gregory Peck Hal Wallis January 30, 1966 TOWN and GOWN University of Southern California PROGRAM I. Opening Dr. Norman Topping, President of USC II. Representing Cinema Dr. Bernard R. Kantor, Chairman, Cinema Ill. Representing DKA Howard A. Myrick Presentation of Associate Awards to Barye Collen, Art Jacobs, Howard Jaffe, Anne Kramer, Robert Knutson, Jerry Wunderlich IV. Presentation of Film Pioneer Award to Frances Marion and Sol Lesser V. Master of Ceramonies Bob Crane VI. Tribute to honorary members of DKA VII. Presentation of Honorary Awards to: Hal Wallis Gregory Peck Lucille Ball VIII. In closing Dr. Norman Topping Banquet Committee of USC Friends and Alumni Mr. Edward Anhalt Mr. Paul Nathan Mr. and Mr. Jim Backus Mr. Tony Owen Mr. Earl Bellamy Mr. Marvin Paige Miss Shirley Booth Miss Mary Pickford Mrs. Harry Brand Miss Debbie Reynolds Mr. -

Celebrating Disneyland’S Golden Anniversary

Celebrating Disneyland’s Golden Anniversary Mickey Mouse and Disneyland Resort President Matt Ouimet are hosting a global party celebrating Disneyland’s 50th anniversary Get Your Kicks With Just One Click. www.anaheim.net Anaheim’s one-stop online calendar is your place for everything happening in the City. Maybe you’re in the mood for a concert at the House of Blues or The Grove, or possibly a game at the Arrowhead Pond. Perhaps you’re planning to see a family show at the Convention Center or you just want to go to a community event sponsored by the City, a local non-profit, or one of Anaheim’s schools. Now there’s one place to get all the info you need...no matter where you’re going in Anaheim. Just log on to the City’s new comprehensive Calendar of Events at www.anaheim.net. And, if you’re an Anaheim-based organization or you’ve got an event taking place in the City, let us know about it. Our Calendar is just one part of a useful city website that has all the information you need for anything related to city operations, pro- grams, services and current events. So visit www.anaheim.net today, where your kicks are just one click away. C ITY OF A NAHEIM www.anaheim.net Features 8 Disneyland at 50 New rides and attractions are part of a global celebration as Anaheim’s most beloved and popular destination turns 50 in a big way. On the Cover 8 13 Through the Decades Mickey Mouse and Disneyland A look at how Disneyland and Anaheim have grown together. -

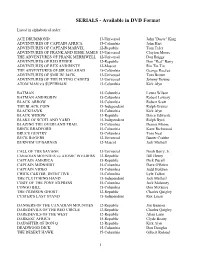

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob Burke Autographs of Western Stars Collection Autographed Images and Ephemera Box 1 Folder: 1. Roy Acuff Black-and-white photograph of singer Roy Acuff with his separate autograph. 2. Claude Akins Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Claude Akins. 3. Alabama Signed color photograph of musical group Alabama. 4. Gary Allan Signed color photograph of musician Gary Allan. 5. Rex Allen Signed black-and-white photograph of singer, actor, and songwriter Rex Allen. 6. June Allyson Signed black-and-white photograph of actor June Allyson. 7. Michael Ansara Black-and-white photograph of actor Michael Ansara, matted with his autograph. 8. Apple Dumpling Gang Black-and-white signed photograph of Tim Conway, Don Knotts, and Harry Morgan in The Apple Dumpling Gang, 1975. 9. James Arness Black-and-white signed photograph of actor James Arness. 10. Eddy Arnold Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Eddy Arnold. 11. Gene Autry Movie Mirror, Vol. 17, No. 5, October 1940. Cover signed by Gene Autry. Includes an article on the Autry movie Carolina Moon. 12. Lauren Bacall Black-and-white signed photograph of Lauren Bacall from Bright Leaf, 1950. 13. Ken Berry Black-and-white photograph of actor Ken Berry, matted with his autograph. 14. Clint Black Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Clint Black. 15. Amanda Blake Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Amanda Blake. 16. Claire Bloom Black-and-white promotional photograph for A Doll’s House, 1973. Signed by Claire Bloom. 17. Ann Blyth Signed black-and-white photograph of actor and singer Ann Blyth. -

Western TV Trivia Questions 1

Western TV Trivia Questions 1. What was the longest running western of all time. 2. Who played Ben Cartwright? 3. In what year did Gunsmoke air? 4. What is the name of Roy Roger's Horse? 5. Who was Gene Autry's sidekick? 6. Who played Hoss Caartwright? 7. In what year did Bonanza air? 8. Name the western that had a character named Paladin? 9. Who played Tonto? 10. Who played Little Joe Cartwright? 11. Who played the part of Paladin? 12. What part did Clayton Moore and John Hart play? 13. Who played Brett Maverick? 14. What was the real name of Hoppalong Cassidy? 15. Who starred in the Rifleman? 16. What is the theme song for The Lone Ranger? 17. Who played Matt Dillon? 18. What is the closing song of the Roy Rogers Show? 19. Two Secret Service agents worked for President Ulysses S. Grant on what show? 20. What was the name of the Lone Ranger's Horse? 21. Who played Davy Crockett? 22. What was Roy Rogers' real name? 23. What was the name of Gene Autry's Horse? 24. What was the name of Dale Evan's Horse? 25. What was the name of Tontop”s Horse? 26. What town was Gunsmoke set in? 27. In what state was Bonanza set in? 28. Barbara Stanwick starred in what western? 29. Clint Eastwood's First starred in what western TV Show? 30. What group did Roy Rogers sing with before he became a movie star? 31. The original movie “Stage Coach” made what actor a star? Western TV Trivia Answers 1. -

The Dallas Digest

Page 1 February 2021 The Dallas Digest The Mayor’s Space Mayor Brian Dalton I actually grew up thinking masks were cool. As in, Zorro, Batman, Spiderman and the Lone Ranger. Famously, “Who was that masked man?” Clayton Moore it turns out, whom I once met, by the way. In the old days us adults didn’t get to wear masks much except at Halloween or occupa- tionally, say the way that Butch and Sundance wore bandanas to rob trains. But times change and we adults now get to wear masks, prudently trying to hide from the virus that is trying to kill us. It does make smiling a challenge, but has the benefit of concealing the need for a shave. Wearing a mask to prevent death seems simple enough in the modern age, particularly in relation to what our ancients tried - ringing church bells or rubbing their bodies with a chopped up pigeon - to thwart the black plague. Or leeches. So, rather than assaulting pigeons or employing leeches, I will join with various modern scientists and pro- pound mask wearing here in the community. Seems simple enough that if you can wear a seatbelt to protect yourself and others in a car crash, why not wear a mask? If nothing else, it sends the message that you care for the well-being of your friends, neighbors and total strangers. Bottom line, the more masking we have, the less disease circulates and the sooner we can all go back to work, out to eat and down to the cinema to see Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol.