Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture 2003

THE HIGH COURT’S ABANDONMENT OF ‘THE TIME-HONOURED METHODOLOGY OF THE COMMON LAW’ IN ITS INTERPRETATION OF NATIVE TITLE IN MIRRIUWUNG GAJERRONG AND YORTA YORTA Sir Ninian Stephen Annual Lecture 2003 Noel Pearson Law School University of Newcastle 17 March 2003 There are fundamental problems with the way in which the High Court has interpreted native title in Australian law in its two most recent decisions: Mirriuwung Gajerrong1 and Yorta Yorta2. In the space of this lecture I will only be able to deal with three key problems: the court‟s misinterpretation of the definition of native title in section 223(1) of the Native Title Act 1993-1998 (Cth) (“Native Title Act”) the court‟s misinterpretation of how the common law treats traditional indigenous occupants of land when the Crown acquires sovereignty over their land as an injusticiable act of State the court‟s disavowal of native title as a doctrine or body of law within the common law – 1 State of Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28 (8 August 2002). Referred to variously as Ward and Mirriuwung Gajerrong 2 Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58 (12 December 2002) 1 and its failure to judge the Yorta Yorta people‟s claim in accordance with this body of law I will close with some views about what I think needs to be done in all justice to indigenous Australians. But before I undertake this critique, let me first set out my understanding of what Mabo3 and native title should have meant to Australians. -

Curriculum Vitae Neil Young Qc

CURRICULUM VITAE NEIL YOUNG QC Address Melbourne Ninian Stephen Chambers (Chambers) Level 38, 140 William Street, Melbourne Vic 3000 Email [email protected] Clerk Michael Green – Ph 03 9225 7864 Sydney New Chambers 126 Phillip Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Email [email protected] Clerk Ian Belshaw – Ph 02 9151 2080 Present position Queen’s Counsel, all Australian States Academic LL.B (1st class honours), University of Melbourne Qualifications LL.M Harvard, 1977 Current Member of the Court of Arbitration for Sport, Geneva, since 1999 professional Director, Victorian Bar Foundation positions Director of the Melbourne Law School Foundation Board Previous Vice-Chairman, Victorian Bar Council, September 1995 to March 1997 professional Director, Barristers’ Chambers Limited, 1994 to 1998 positions Chairman of the Victorian Bar Council, March 1997 to September 1998 President, Australian Bar Association, January 1999 to February 2000 Member, Faculty of Law, University of Melbourne, 1997 2005 Member of the Monash University Faculty of Law Selection Committee, 1998 Member of the JD Advisory Board, Melbourne University, since 1999 Member of the Steering Committee, Forum of Barristers and Advocates of the International Bar Association, January 1999 to February 2000 Member of the Trade Practices and Taxation Law Committees of the Law Council of Australia Chairman of the Continuing Legal Education Committee of the Victorian Bar, 2003 – November 2005 Justice of the Federal Court of Australia, 2005-2007 Page 1 of 2 Admission Details Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria since 3 March 1975 Practitioner of the High Court of Australia and the Federal Court since 3 April 1975 Signed the Victorian Bar Roll on 15 March 1979 Admitted as a barrister, or barrister and solicitor in each of the other States of Australia Appointment Appointed one of Her Majesty’s Counsel for the State of Victoria on 27 November to the Inner Bar 1990. -

Referendum - the Australian Way

THE SEVENTH SIR JOHN QUICK BENDIGO LECTURE REFERENDUM - THE AUSTRALIAN WAY THE RT HON SIR NINIAN STEPHEN SIR JOHN QUICK LECTURE 11 OCTOBER 2000 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY, BENDIGO ISSN 1325 - 0787 The publication of the Year 2000 Lecture is generously supported by Robertson HYETTS Solicitors, Molesworth Chambers, 51 Bull Street, Bendigo. Sir John Quick was a partner in the Bendigo law firm, Quick Hyett and Rymer, later Quick and Hyett, from 1890 to 1912. From 1891 the firm practised from premises at 51 Bull Street. Robertson Hyetts are proud to be associated with the Sir John Quick Lecture. REFERENDUM - THE AUSTRALIAN WAY THE RT HON SIR NINIAN STEPHEN When asked to give this Sir John Quick Lecture I immediately thought of s.128 of our Constitution and its referendum procedure, so closely associated with John Quick, whose memory this series of lectures honours. The most intriguing thing about the Australian form of Constitutional referendum is surely how we ever came to have it formally written into our constitution. In 1900 the referendum was not only a very rare feature of constitutions world wide; it was directly opposed to the principle of representative democracy which Australia had inherited from Britain and which before federation was accepted by all six of the Australian colonies as the normal and very traditional form of government. It was that principle which Edmund Burke described when, in his speech to the electors of Bristol in 1774, he said "you choose a member indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a Member of Parliament". -

Dialogue Vol. 22, 2/2003

he Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia was established in 1971. T Previously, some of the functions were carried out through the Social Science Research Council of Australia, established in 1942. Elected to the Academy for distinguished contributions to the social sciences, the 382 Fellows of the Academy offer expertise in the fields of accounting, anthropology, demography, economics, economic history, education, geography, history, law, linguistics, philosophy, political science, psychology, social medicine, sociology and statistics. The Academy’s objectives are: · to promote excellence in and encourage the advancement of the social sciences in Australia; · to act as a coordinating group for the promotion of research and teaching in the social sciences; · to foster excellence in research and to subsidise the publication of studies in the social sciences; · to encourage and assist in the formation of other national associations or institutions for the promotion of the social sciences or any branch of them; · to promote international scholarly cooperation and to act as an Australian national member of international organisations concerned with the social sciences; · to act as consultant and adviser in regard to the social sciences; and, · to comment where appropriate on national needs and priorities in the area of the social sciences. These objectives are fulfilled through a program of activities, research projects, independent advice to government and the community, publication and cooperation with fellow institutions both within -

Religious Freedom and the Australian Constitution – Origins and Future

The Denning Law Journal 2018 Vol 30 pp 207-217 RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND THE AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTION – ORIGINS AND FUTURE Luke Beck (Routledge 2018) pp 178 Jocelynne A. Scutt* The most recent Australian Census, conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 2016 (with a 95.1 per cent response rate), confirms that Australia is ‘increasingly a story of religious diversity, with Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, and Buddhism all increasingly common religious beliefs’.1 Of these, between 2006 and 2016 Hinduism shows the ‘most significant growth’, attribut- ed to immigration from South East Asia, whilst Islam (2.6 per cent of the popu- lation) and Buddhism (2.4 per cent) were the most common religions reported next to Christianity, the latter ‘remaining the most common religion’ (52 per cent stating this as their belief). Nevertheless, Christianity is declining, drop- ping from 88 per cent in 1966 to 74 per cent in 1991, and thence to the 2016 figure. At the same time, nearly one-third of Australians (30 per cent) state they have no religion,2 this group reflecting ‘a trend for decades’ which, says the ABS, is ‘accelerating’: Those reporting no religion increased noticeably from 19% in 2006 to 30% in 2016 [with] the largest change … between 2011 (22%) and 2016, when an additional 2.2 million people reported having no religion.3 In this, there were not insignificant differences between the states: Tasmania reported the lowest religious affiliation rate (53 per cent), whilst New South Wales had the highest rate (66 per cent). Age was a significant factor, both in terms of particular religious affiliation and in the ‘no religion’ category. -

Annual Report 2014-2015 HAEMOPHILIA FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA

annual report 2014-2015 HAEMOPHILIA FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA Haemophilia Foundation Australia (HFA) is the national peak body which represents people with haemophilia, von Willebrand disorder and other rare inherited bleeding disorders and their families throughout Australia. HFA supports a network of state and territory Foundations in Australia and as a National Member Organisation of the World Federation of Hemophilia, HFA participates in international efforts to improve access to care and treatment for people with bleeding disorders around the world. Our Mission: to inspire excellence in treatment, care and support through representation, education and promotion of research. Our Vision: for people with bleeding disorders to lead active, independent and fulfilling lives. Our Goals: good governance effective advocacy strategic education and communication financial sustainability to advance research, care and treatment to be the trusted national organisation and recognised community expert on inherited bleeding disorders Our Governance HFA is incorporated in Victoria. Its members are each of the state/territory Haemophilia Foundations around Australia. Each Foundation is represented on the HFA Council and Council elects office-bearers from its own number. At the Annual General Meeting on 25 October 2014, a special resolution to change the HFA Constitution was considered. This had been preceded by a full consultation with members and legal advice. The HFA Council subsequently adopted a number of Constitution changes aimed at creating a smaller, more efficient and agile Council. The effect of the changes was that there would no longer be an Executive Board and each member Haemophilia Foundation would have just one representative on Council. Executive Board meetings would be replaced with up to 3 Council meetings during the year. -

Australia and Contentious Cases

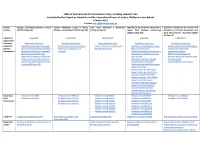

Table of Australia and ICJ Contentious Cases, including relevant links Compiled by the Project on Australia and the International Court of Justice, Melbourne Law School February 2019 Contact: [email protected] Official Nuclear Tests (New Zealand v. France) Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru East Timor (Portugal v Australia) Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v. Questions relating to the Seizure and Citation [1974] ICJ Rep 457 (Nauru v. Australia) [1992] ICJ Rep 240 [1995] ICJ Rep 90 Japan: New Zealand Intervening) Detention of Certain Documents and [2014] ICJ Rep 226 Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia) [2015] ICJ Rep 147 Australia’s Applicant Respondent Respondent Applicant Respondent Appearance Overview Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Australia’s - Application Instituting Proceedings - Counter-Memorial of Australia - Counter-Memorial of Australia - Application instituting proceedings - Written observations of Australia on Written - Request for the indication of Interim - Preliminary Objections of - Rejoinder of Australia - Memorial of Australia Timor-Leste's Request for Submissions Measures of Protection of Australia Australia - Written observations of Australia on provisional measures - Memorial on Jurisdiction and the Declaration of Intervention by - Written Undertaking by the Admissibility submitted of Australia New Zealand Attorney-General of Australia dated - Written answer of Australia to the - Statement of Mr Marc Mangel 21 January 2014 question posed by Judge Gros at the (expert called by Australia) - Counter-Memorial of Australia hearing of 25 May 1973 - Statement of Mr Nick Gales (expert called by Australia) - Statement of Mr. Nick Gales (expert called by Australia) in response to the statement submitted by Mr. -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J. -

Australia's First Bill of Rights – Testing Judicial Independence and the Human Rights Imperative

Australia’s First Bill of Rights – Testing Judicial Independence and the Human Rights Imperative - Delivered at the National Press Club by Chief Justice Terence Higgins Wednesday 3 March 2004 At around midnight last night, the Legislative Assembly of the Australian Capital Territory, Australia’s smallest territory, enacted a legislative innovation that has the potential to fundamentally alter the way we think about, administer and protect the fundamental human rights of all people within our land. In time it may stand as an example for far wider, even constitutional, reform in other Australian jurisdictions. I refer to the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT) - Australia’s first ever Bill of Rights. Although there has been much debate in the assembly over the inclusion of further kinds of rights, the value of the ideals finally enshrined within the Act is surely beyond argument.1 They are substantially derived from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Australia is already a party.2 Without taking any view as to how they may be interpreted, they include such rights as the right to peaceful assembly, and freedoms of association (s 15), movement (s 13), expression (s 16), thought, conscience, religion and belief (s 14). 1 Roderick Campbell, “Libs to Seek Change to Bill of Rights”, The Canberra Times, 1 March 2004. 2 Similar principles already permeate international resolutions and dialogue – eg. GA Resolution 55.2 United Nations Millennium Declaration, paras 4 ‘human rights and fundamental freedoms’, 9 ‘respect for the rule of law’ and Part V, ‘Human Rights, Democracy and Good Governance’. -

Imagereal Capture

IDDRESS ADDRESSTOTHEBDPS Those of you who travel into the City were so many counsel present. ANNUAL DINNER from the south-east may use The only available location large Kingsway. You will know the King's enough to accommodate the Justice Stephen Charles Bridge. It was completed in 1961 at Commission and counsel was the Judge of the Court of Appeal considerable expense to the Hawthorn Town Hall, which had a of Victoria community. In 1962 a man called recording and sound magnifying Noble drove over it with a very system which enlivened The following is the text of the large vehicle. The bridge broke. In proceedings by frequently address given by Justice Stephen the ensuing uproar, the Premier, Sir broadcasting radio transmissions of Charles to the Annual Dinner of the Henry Bolte, decided there would passing taxis. The system would BOPS at the Hilton Hotel on 27 be a Royal Commission. John suddenly broadcast 'there's no-one June 2001. Starke was then the leader of the here' followed by the taxi driver's Victorian Bar and probably of the expletives non-deleted. Starke Australian Common Law Bar. He himselfwas a hugeman, a regularly acted interstate in major dominating and very intimidating matters. Starke was briefed for the cross-examiner. I sat at the Bar principal contractor Utah table between Starke and Dawson. Construction Co. During the course On occasions itwas like being of the Royal Commission, Starke beside a rhinoceros of uncertain but also defended Robert Peter Tait, a potentially very hostile disposition. man of unsound mind who Starke had gout. -

The High Court's Ambassadors: Latham, Dixon and Stephen Compared

THE HIGH COURT’S AMBASSADORS: LATHAM, DIXON AND STEPHEN COMPARED Introduced by the Hon Justice Susan Crennan AC Dr Philip Ayres high court of australia public lecture High Court of Australia Canberra, Courtroom 1 10 September 2014 — 6pm RSVP by 3 Sept 2014 [email protected] Inquiries (02) 6270 6893 Dr Philip Ayres by Clarendon Press Oxford and is the author of two major judicial biographies Cambridge University Press. He is a (Owen Dixon and Fortunate Voyager: Fellow of both the Royal Historical Society The Worlds of Ninian Stephen), a Prime (London) and the Australian Academy Ministerial biography (Malcolm Fraser), the of the Humanities, and a recipient of the biography of Cardinal Moran (Prince of the Centenary Medal for services to literature. Church), and the only whole-of-life scholarly He taught at the University of Adelaide, biography of Mawson, as well as books on Monash University, Vassar College and eighteenth-century British culture published Boston University. ABSTRACT On leave from the High Court of Australia, Ambassador for the Environment before Chief Justice Sir John Latham served as undertaking international mediatory roles Australia’s Minister to Japan from 1940 to in Northern Ireland and Bangladesh and 1941. Sir Owen Dixon took similar leave to leading UN missions to Cambodia and be Australia’s Minister to the United States Burma. How ably did these judges perform from 1942 to 1944. Sir Ninian Stephen, as ambassadors, and does the judicial role following his years on the Court and then augur well for the ambassadorial role? as Governor-General, served as Australian Refreshments to follow, All welcome RSVP by 3 Sept 2014 [email protected] Inquiries (02) 6270 6893. -

1 Sir Harry Gibbs a Paper Presented

Sir Harry Gibbs A paper presented to the Selden Society, Brisbane on 17 March 2016 by D.F. Jackson AM, QC1 Introduction I thank the Selden Society for inviting me to deliver this paper in relation to the life of Sir Harry Gibbs, who was born on 7 February 1917 and died on 25 June 2005. I had the privilege to be his Associate in 1963 and 1964 when he was a Judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, I appeared before him after that on a number of occasions when he was a Judge of that Court, and on many occasions I appeared before courts of which he was a member in the High Court, sometimes in cases which were acutely political. After his retirement we kept in contact and I was pleased that he sent a message asking me to visit him in hospital a few days before his death. He was then a very sick man. We both knew he was dying. And we uttered the trivialities and banalities so common on such occasions. Other material May I mention first some of the places where other material concerning him is to be found. The fullest is a biography of Sir Harry by Joan Priest, Without Fear or Favour. It was published in 1995 sponsored by the University of Queensland Law Graduates Association. It contains an Appendix by the Hon Peter Connolly CBE, QC a former Judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland, dealing with Sir Harry’s time on the High Court, and thereafter. In 2003 the Supreme Court Library published Queensland Judges on the High Court, edited by Michael White QC and Adam Rahemtula .