Peter W.E. Kidner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Residents 21.Pub

Bawdrip Village Welcome Pack Welcome to Bawdrip On behalf of The Parish Council, let me welcome you to Bawdrip. We hope that the information given in this Welcome Pack will help you to settle more comfortably into your new home and the village. Neighbours usually become your first contacts and advisors, but please feel free to telephone any of the Councillors or Clerk for information and help. As residents, we trust that you will quickly become and feel part of this community. We have tried to gather as much useful local information as possible, but would be pleased to hear any suggestions or improvements you might have about this pack. More local information is available via the village website at www.bawdrip.org.uk and through its links to other local websites. Also the website carries the most up to date version of this document. We wish you many happy years in Bawdrip and hope that you will join with us in creating a vibrant and friendly community. Richard Culverhouse Chairman of the Parish Council Contents Page History of Bawdrip 3 Parish Map 4 Your Parish Councillors 5 Other Village Representatives 6 St Michaels and All Angels Church 7 Other religious establishments 7 Useful local information 8 Publications 8 Health facilities 9 Shopping 9 Education 9 Emergency Services 10 Public Transport 10 Recycling and Civic Amenity Sites 10 Clubs and Societies 11 2 13 History of Bawdrip Bawdrip is a small, unique village nestling on the southern slopes of the Polden Hills and, at the beginning of 2002, the core of the village remained relatively unchanged by the onslaught of development which has taken place in many rural settlements. -

'Off-The-Beaten Track' Sightseeing Tour of Central Exmoor

‘Off-the-Beaten Track’ Sightseeing Tour of Central Exmoor Central Tour of Sightseeing Track’ ‘Off-the-Beaten B G F C E D A N H L M I J K G Places of interest along the route Overlay of route This map is intended as a guide only. © Exmoor National Park Authority Circular drive around central Exmoor This drive through the beautiful scenery of Exmoor, is designed to give you an ‘off-the-beaten-track’ sightseeing tour with plenty to do along the way. It includes small single-track roads which have passing places and a picturesque toll road. The information starts at Porlock, but you can pick up the route anywhere along it, depending on where you are staying. Places of interest are listed and numbered in the order you reach them going anti-clockwise around the route, which is the recommended direction to follow. Remember to take your binoculars with you, as you have a good chance of seeing red deer herds on this route, as well as Exmoor ponies. Distance: about 36 miles Duration, including stops: all day. Please note: This route is not suitable for larger vehicles. Main towns and villages visited Porlock, Porlock Weir, Oare, Brendon, Rockford, Simonsbath, Exford, Stoke Pero, Cloutsham, Horner. Places of interest along the way A. Porlock – Doverhay Manor Museum, St Dubricius church, Greencombe Gardens B. Porlock Weir (off route) – harbour, boat museum, Exmoor Glass, Porlock Marsh, Culbone church C. Toll road through ancient woodlands D. Oare church (Lorna Doone story) E. Malmsmead – Doone valley, tea rooms, old pack horse bridge, walks F. -

1911 Census by Group (Version4)

First name Surname Age in 1911: Est. Birth Year: Relation to Head: Gender: Birth Place: Street address: Marital Status: Yrs Married: Est. Marriage Year: Occupation: 1 Peter B Collings 89 abt 1822 Head Male Guernsey Uplands, Bawdrip Widowed Clergyman Established Church 1 Ada G Collings 50 abt 1861 Daughter Female Sutton Valence, Kent Uplands, Bawdrip Single Private Means 1 Maud Collings 38 abt 1873 Daughter Female Dover, Kent Uplands, Bawdrip Single Private Means 1 Bessie Poole 29 abt 1882 Servant Female Puriton, Somerset Uplands, Bawdrip Single Parlourmaid 1 Bessie Bishop 26 abt 1885 Servant Female Broomfield, Somerset Uplands, Bawdrip, Single Cook 1 Hida Crane 23 abt 1888 Servant Female Bawdrip, Somerset Uplands, Bawdrip Single Housemaid 1 Jane Parsons 18 abt 1893 Servant Female Puriton, Somerset Uplands, Bawdrip Single Kitchen maid 1 Frederick Crane 18 abt 1893 Servant Male Bawdrip, Somerset Uplands, Bawdrip Single Groom Domestic 2 John Stone 48 abt 1863 Boarder Male Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip Carter On Farm 2 Simon Stone 43 abt 1868 Head Male Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip Married 20 1891 Waggoner 2 Florence Stone 38 abt 1873 Wife Female Puniton, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip Married 2 John Collier 33 abt 1878 Boarder Male Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip stone Quarryman 2 Walter Stone 17 abt 1894 Son Male Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip Single Cowman 2 Oliver Stone 14 abt 1897 Son Male Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip Blind at 11yrs 2 Ada Stone 8 abt 1903 Daughter Female Bawdrip, Somerset New Road, Bawdrip 2 Minnie -

Somerset Parish Reg Sters

S om e rs e t Pa ris h m r a riages. E DITE D BY . PH IL LIM OR E . W P W , M A , A N D W . A . BELL , R ector o Charl nch f y , A ND C . W . WH ISTLER , M . R . C . S Vicar ofS tockland . VOL VI 1 011 0011 m) T E UBS C R IBER S BY P ss u o TH H ILLIM OR E C o . I S , 1 2 H A NCER Y A NE 4 , C L , P R E F A C E . A sixth volu me of Somer set Marriage Regi sters is now s completed , making the total number of parishe dealt - with to be forty nine . 1 379239 A s s u se of before , contraction have been made w - o r i o — h . o . o . i o s of wid wer w d w di c the di ce e . — - b . a e o c o in h . t e ou of b ch l r c nty . — m — s s i e o a . i m a e l e . s e s Z a . pin t r, ngl w n arri g ic nce d — — m au e . e o a . d ght r . y y n . — — . oi th e a is of c a e n e . p p r h . c rp t r The reader mu st remember that the printed volumes “ ! fi are not evidence in the legal sen se . Certi cate s must l of be obtained from the ocal clergy in charge the Regi sters. -

Early Transport on Exmoor by Jan Lowy

Early transport on Exmoor By Jan Lowy This work is based on notes made for the presentation to the Local History Group, December 2020 Map of West Somerset to Tiverton This shows the area we are mainly talking about. This map is dated 1794. Packhorse bridge at Clickit For centuries men used feet to get about, then horses, then horse and cart, and horse and carriage. There were also boats on rivers and round the coast. On land they needed marked routes to follow, which needed to be kept clear. Stone age people travelled long distances in search of suitable flints for their tools and weapons, but it was during the Bronze age (3000 – 1200BC) that tracks were regularly used - probably something like this. Often on high ground, enabling travellers to see hazards more easily, including those with criminal intentions, avoiding densely wooded and marshy river valleys until forced to descend to cross streams. Just off road to Webbers Post Many modern roads follow the same route: long distance routes such as across the Blackdown and Brendon hills linking the ridgeways of Dorset and Wiltshire with Devon, (as here) and local routes, like tracks along the Quantocks, Mendips and Poldens. As we know, the Romans built a national system of good roads, but after the Romans left the roads were not maintained. There were not many wheeled vehicles, and fewer long journeys, so only local tracks were needed. By the Middle Ages, there was again considerable traffic on the roads. Each parish was responsible for maintaining the roads within its bounds. -

10000 515000 ! 520000 525000 !

! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! !! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! ! !! ! !! !! !! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! !! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! !! ! !! !! ! ! !! !! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! !! !! ! ! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! ! !! !! ! !! !! !! !! !! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! !! !! ! ! !! !! !! !! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 490000 495000 500000 505000 510000 515000 ! 520000 525000 ! ! ! ! 3°12'30"O 3°10'0"O 3°7'30"O 3°5'0"O 3°2'30"O 3°0'0"O 2°57'30"O 2°55'0"O 2°52'30"O 2°50'0"O 2°47'30"O 2°4! 5! '0"O 2°42'30"O 2°40'0"O 2°37'30"O ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! N GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR-069 ! ! ! " N ! ! " ! ! 0 !! 0 ! ! ! 3 ! ' 3 ! ! ' ! ! 2 Product N.: 02Bridgwater, v2 ! ! 2 ! ! ! 1 E ! ³ ! ° 1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! !! ° ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 ! ! ! ! ! -

EXMO Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

EXMO bus time schedule & line map EXMO Lynmouth View In Website Mode The EXMO bus line (Lynmouth) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lynmouth: 9:25 AM - 4:00 PM (2) Minehead: 10:40 AM - 5:10 PM (3) Minehead: 11:10 AM - 2:10 PM (4) Williton: 10:05 AM - 4:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest EXMO bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next EXMO bus arriving. Direction: Lynmouth EXMO bus Time Schedule 39 stops Lynmouth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Haven Caravan Park, Williton Tuesday Not Operational Doniford Farm, Doniford Wednesday 9:25 AM - 4:00 PM Kingsland, Watchet Thursday 9:25 AM - 4:00 PM Kingsland, Watchet Friday 9:25 AM - 4:00 PM Watchet Railway Station, Watchet Harbour Road, Watchet Saturday 9:25 AM - 4:00 PM Lorna Doone Caravan Park, Watchet Lorna Doone, Watchet Warren Bay Caravan Park, St Decuman's EXMO bus Info Direction: Lynmouth Warren Farm, Old Cleeve Stops: 39 Trip Duration: 60 min Beeches Camp Site, Chapel Cleeve Line Summary: Haven Caravan Park, Williton, Doniford Farm, Doniford, Kingsland, Watchet, Hoburne Blue Anchor, Blue Anchor Watchet Railway Station, Watchet, Lorna Doone Caravan Park, Watchet, Warren Bay Caravan Park, Driftwood Cafe, Blue Anchor St Decuman's, Warren Farm, Old Cleeve, Beeches Camp Site, Chapel Cleeve, Hoburne Blue Anchor, Blue Anchor, Driftwood Cafe, Blue Anchor, West Somerset West Somerset Railway Station, Blue Anchor Railway Station, Blue Anchor, Post O∆ce, Carhampton, Dunster Showground, Dunster, Dunster -

Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2

Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2 WWW.SOMERSET.GOV.UK WELCOME TO THE 2ND SOMERSET RIGHTS OF WAY IMPROVEMENT PLAN Public Rights of Way are more than a valuable recreational resource - they are also an important asset in terms of the rural economy, tourism, sustainable transport, social inclusion and health and well being. The public rights of way network is key to enabling residents and visitors alike to access services and enjoy the beauty of Somerset’s diverse natural and built environment. Over the next few years, the focus is going to be chiefly on performing our statutory duties. However, where resources allow we will strive to implement the key priority areas of this 2nd Improvement Plan and make Somerset a place and a destination for enjoyable walking, riding and cycling. Harvey Siggs Cabinet Member Highways and Transport Rights of Way Improvement Plan (1) OVERVIEW Network Assets: This Rights of Way Improvement Plan (RoWIP) is the prime means by which Somerset County • 15,000 gates Council (SCC) will manage the Rights of Way Service for the benefit of walkers, equestrians, • 10,000 signposts cyclists, and those with visual or mobility difficulties. • 11,000 stiles • 1300+ culverts The first RoWIP was adopted in 2006, since that time although ease of use of the existing • 2800+ bridges <6m network has greatly improved, the extent of the public rights of way (PRoW) network has • 400+ bridges >6m changed very little. Although many of the actions have been completed, the Network Assessment undertaken for the first RoWIP is still relevant for RoWIP2. Somerset has one of the There are 5 main aims of RoWIP2: longest rights of way networks in the country – it currently • Raise the strategic profile of the public rights of way network stands at 6138 km. -

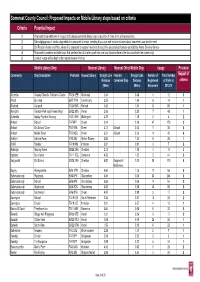

Consultation List of Mobile Stops and Potential Impact.Xlsx

Somerset County Council: Proposed Impacts on Mobile Library stops based on criteria Criteria Potential Impact 1 Proposed to be withdrawn in August 2015 because mobile library stop is less than 3 miles from a library building 2 School/playgroup or similar stop which it is proposed to retain, pending discussion with each institution about how needs can best be met 3 Old People's home or similar, where it is proposed to support residents through the personalised service provided by Home Delivery Service 4 Proposed to combine multiple stops that are less than 0.5 miles apart into one stop (location/time to be discussed with the community) 5 Level of usage will be kept under regular review in future Mobile Library Stop Nearest Library Nearest Other Mobile Stop Usage Potential Community Stop Description Postcode Nearest Library Straight Line Possible Straight Line Number of Total Number impact of Distance Combined Stop Distance Registered of Visits in criteria (Miles) (Miles) Borrowers 2013/14 Alcombe Cheeky Cherubs Children’s Centre TA24 5EB Minehead 0.64 0.38 1 12 2 Alford Bus stop BA7 7PWCastle Cary 2.05 1.44 6 19 1 Allerford Car park TA24 8HSPorlock 1.36 1.01 8 80 1 Alvington Fairacre Park (opp Fennel Way) BA22 8SA Yeovil 2.06 0.20 7 48 1 Ashbrittle Appley Pavillion Nursery TA21 0HH Wellington 4.22 1.18 2 4 2 Ashcott School TA79PP Street 3.04 0.18 47 179 2 Ashcott Old School Close TA7 9RA Street 3.12 Ashcott 0.13 11 35 4 Ashcott Middle Street TA7 9QG Street 3.01 Ashcott 0.13 14 45 4 Ashford Ashford Farm TA5 2NL Nether Stowey 2.86 1.10 6 -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS52117.TXT

M127-7 SEDGEMOOR DISTRICT COUNCIL CANDIDATES SUMMARY PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION - 3RD MAY 2007 Area Candidates Party Address Parish of Ashcott Adrian Scot Davis 20 School Hill, Ashcott, Somerset, DAVIS TA7 9PN Number of Seats : 8 Cilla Ann Thurlow Grain Ashcott Resident 3 Pedwell Lane, Ashcott, Bridgwater, GRAIN Somerset, TA7 9PD Joe Jenkins Saddle Stones, 31 Pedwell Hill, JENKINS Ashcott, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA7 9BD Jenny Lawrence 3 The Batch, Ashcott, Bridgwater, LAWRENCE Somerset, TA7 9PG Jack Miles Sayer 29 High Street, Ashcott, Bridgwater, SAYER TA7 9PZ Axbridge Town Council Dennis Bratt Past Mayor of Axbridge 62 Knightstone Close, Axbridge, BRATT Somerset, BS26 2DJ Number of Seats : 13 Kate Walker Independent 36 Houlgate Way, Axbridge, Somerset, Browne BS26 2BY BROWNE Christopher Byrne Wavering Down, Webbington Road, BYRNE Cross, Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2EL Jeremy Gall 6 Moorland St, Axbridge, BS26 2BA GALL Pauline Ann Ham 15 Hippisley Drive, Axbridge, HAM Somerset, BS26 2DE Barry Edward Hamblin 40 West Street, Axbridge, Somerset, HAMBLIN BS26 2AD Val Isaac Vine Cottage, 50 West Street, ISAAC Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2AD James A H Lukins Retired Farmer Townsend House, Axbridge LUKINS Andrew Robert Matthews The Cottage, Horns Lane, Axbridge, MATTHEWS Somerset, BS26 2AE Paul Leslie Passey Somerhayes, Jubilee Road, Axbridge, PASSEY Somerset, BS26 2DA Elizabeth Beryl Scott Moorland Farm, Axbridge, Somerset, SCOTT BS26 2BA Michael Taylor Mornington House, Compton Lane, TAYLOR Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2HP Jennifer Mary Trotman 4 Bailiff's -

The Exmoor Society 23Rd Society Walk – Murder and Mystery at Wheal Eliza (Re Simonsbath Frestival)

The Exmoor Society 23rd Society Walk – Murder and Mystery at Wheal Eliza (re Simonsbath Frestival). On this short walk along the River Barle, hear the history of the Knights’ family, mining in this part of Exmoor Calendar of Society & Group Events and the tragic murder and mystery at Wheal Eliza. One or two short climbs but overall an easy 2019 walk along the valley. Return to Simonsbath for pub lunch or bring a picnic. 2.5mls. Meet 10.30am Ashcombe Car Park, Simonsbath TA24 7SH / SS 775 394. Ref RT 23rd Bristol Group – AGM 7.30pm, KRMC. Followed by a talk - “Dastardly Deeds at Dulverton”. JANUARY 24th Society Walk – Doone Country - Heroes, Heroines, Hunter-gatherers and Hermits (re 10th Bristol Group – 2 mile walk then lunch at The Star, near Shipham, BS25 1QE. Meet 11am for the Simonsbath Festival). Join Rob Wilson-North for a walk over rough moorland to Badgworthy, in walk or 12.30pm for lunch. the footsteps of author RD Blackmore (in the 150th year of the publication of Lorna Doone); and 19th Bristol Group – Winter supper at St Andrew’s Church Hall, Clevedon, BS21 7UE. 7.00pm for also on the trails of hermits and hunter-gatherers. Bring a packed lunch/refreshments. 4mls. Dogs 7.30pm. Booking essential on leads. Meet 10.30am Brendon Two Gates SS 765 433. Ref RW-N FEBRUARY 25th Society Walk – Trentishoe Down & the SW Coast Path. Starting on Trentishoe Down, the walk 2nd S Molton Group – Annual Dinner. South Molton Methodist Hall. 7.30pm visits the church at Trentishoe before skirting along Heddon’s Mouth Cleave to reach the coast 20th Coastal Group – “Coleridge Cottage, a Romantic Revival,” Illustrated talk by Stephen Hayes, path. -

Sedgemoor 1685

English Heritage Battlefield Report: Sedgemoor 1685 Sedgemoor (6 July 1685) Parishes: Chedzoy, Westonzoyland District: Sedgemoor County: Somerset Grid Ref: ST 352357 (centred on the battlefield monument) Historical Context The Monmouth Rebellion of June-July 1685 had its roots in the Exclusion Crisis of the late 1670s, when there had existed a popular movement to remove the Roman Catholic James, Duke of York, from the succession to the throne. A key figure in the agitation was James Scott, Duke of Monmouth. As King Charles II's eldest bastard son he stood to benefit if the Duke of York, the King's brother and legitimate heir, ceased to be next in line to the throne. Rumours began to circulate that King Charles had secretly married Monmouth’s mother which, since Monmouth was a protestant and, following his victory against rebels in Scotland at Bothwell Bridge (June 1679), immensely popular, people were more than willing to believe. Substituting the Duke of Monmouth for the Duke of York as King Charles's heir appeared a simple solution to the difficulties currently besetting the state. Indeed, so seductive was the message that Charles, who had a profound respect for the natural succession, more than once, early in 1680, felt it necessary to deny that he had ever married Monmouth's mother. In August 1680 Monmouth made a triumphal tour of the West, which at the time was likened to a Royal progress. The tour, however, was in many ways the high water mark of his success. During 1682 and 1683 he became involved in intrigues directed not only against the Duke of York but ultimately the King himself.