Post Patriarchal Pandoras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You Like Percy Jackson and Rick Riordan Juvenile Science Fiction

If You Like Percy Jackson and Rick Riordan Juvenile Science Fiction/Fantasy J F AND Frostborn (Thrones and Bones) Lou Anders Destined to take over his family farm in Norrøngard, Karn would rather play the board game, Thrones and Bones, until half-human, half frost giantess Thianna appears and they set out on an adventure, chased by a dragon, undead warriors, an evil uncle, and more. J F BEC The Star Thief Lindsey Becker Young parlor maid Honorine and her friend Francis find themselves in the middle of an epic feud between a crew of scientific sailors and the magical constellations come to life. J F SER The Storm Runner J.C. Cervantes To prevent the Mayan gods from battling each other and destroying the world, thirteen-year-old Zane must unravel an ancient prophecy, stop an evil god, and discover how the physical disability that makes him reliant on a cane also connects him to his father and his ancestry. J F CHO Aru Shah and the End of Time Roshani Chokshi Twelve-year-old Aru Shah has the tendency to stretch the truth to fit in at school. Three schoolmates don't believe her claim that the museum's Lamp of Bharata is cursed, and they dare Aru to prove it. But lighting the lamp has dire consequences. Her classmates and beloved mother are frozen in time, and it's up to Aru to save them. J F DAS The Serpent's Secret Sayantani DasGupta Up until her twelfth birthday, Kiranmala considered herself an ordinary sixth- grader in Parsippany, New Jersey, but then her parents disappear and a drooling rakkhosh demon shows up in her kitchen. -

Read Book Uranus and the Bubbles of Trouble

URANUS AND THE BUBBLES OF TROUBLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joan Holub,Social Development Consultant Suzanne Williams,Craig Phillips | 128 pages | 01 Jan 2016 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781481435123 | English | New York, United States Uranus and the Bubbles of Trouble PDF Book For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Debbie rated it liked it Apr 11, Mary Judah Rudd rated it really liked it Dec 18, This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Joan Holub Suzanne Williams Dec I agree to the Terms and Conditions. Summary Add a Summary. Showing Read more LK rated it it was amazing Apr 02, Account Options Sign in. Sorry, but we can't respond to individual comments. Cassandra the Lucky Goddess Girls Series She lives in North Carolina and is online at JoanHolub. Walmart Services. She has an amazing talent— but will Join little Aphrodite for a sweet adventure in this third Little Goddess Girls story—part of Overview A clash between the Titans and The Olympians at sea leaves Zeus and his friends shipwrecked—and in a tidal wave of trouble—in this Heroes in Training adventure. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. As broken stars and hunks of clouds crash to earth and into the sea around the Olympians and their ship, they manage to escape--thanks to some help from Zeus's medallion and guide, Chip--but find themselves shipwrecked. No sooner did he think this than a deep voice boomed from overhead. Comment Add a Comment. Visit him at CraigPhillips. Taekjin Kim rated it it was amazing Apr 13, Browse Browse, collapsed Browse. -

Greek Mythology OS J 292

More to check out: Ubgru & Edgar Parin d’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths Ingri d’Aulaire, Edgar Parin d’Aulaire Greek Mythology OS J 292. DAUL, I A classic, illustrated, collection of Greek myths. Greek Mythology (Junior Genius Guides # 1) | Ken Jennings J 292.13 JENN, K Provides facts on the classic myths of the Greeks and Romans, from how Prometheus outsmarted the gods to how Achilles's heel led to his death. “Help! These books aren’t my thing!” That’s okay! We all read at our own pace and Aurora Public Library have our own likes and dislikes. A librarian Kiwanis Children’s Center can help you find a book that you will love. 630-264-4123 Ask us! aurorapubliclibrary.org Athena the Brain (Goddess Girls #1) | Joan Holub Pandora Gets Jealous | Carolyn Hennesy J HOLU, J J HENN, C Thirteen-year-old Pandy is hauled before Zeus and given six months to gather all of Athena learns that she is a goddess when she is summoned to Mount Olympus by the evils that were released when the box she brought to school as her annual her father, Zeus, and she must quickly adjust to her new status, make friends with project was accidentally opened. the other godboys and goddessgirls, and catch up with all the studies she missed while attending mortal school. Perseus and Medusa: a graphic novel | Blake A. Hoena Get to work, Hercules! (Myth-o-mania #7) | Kate McMullan JGN HOEN, B J MCMU, K In this graphic retelling of the Greek myth, young Perseus is ordered to slay Medusa, a monster whose gaze turns men into solid stone. -

Athena the Brain #1 Aladdin Paperbacks Persephone the Phony

top back by Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams Join the class at Mount Olympus Academy with the series that puts a modern spin on classic Greek myths! Athena the Brain #1 Finding out I’m a goddess and going to MOA brings new friends, a weird dad, and the meanest girl in mythology—Medusa! Persephone the Phony #2 Hiding my feelings works fine until I meet a guy I can be myself with—Hades, the bad-boy of the Underworld. Aphrodite the Beauty #3 Sure I’m beautiful, but it’s not always easy being the goddessgirl of love and beauty. Artemis the Brave #4 I may be the goddess of the hunt, but that doesn’t mean I always feel brave. Athena the Wise #5 Zeus says Heracles has to do 12 tasks or he’ll get kicked out of MOA. I’m not sure it’s wise, but I’m helping out. Aphrodite the Diva #6 Isis claims she’s the goddess of love? Ha! But to keep my title, I must find the perfect match for Pygmalion, the most annoying boy ever. Artemis the Loyal #7 MOA’s Olympic Games are boys-only. No fair! Medusa the Mean #8 I just want to be immortal like those popular goddessgirls. Is that too much for a mortal to ask? The Girl Games (Super Special) Listen in on what all 4 goddessgirls are thinking as MOA hosts visitors from other lands—including a cute kitten! Pandora the Curious #9 Oops! All I did was open Epimetheus’s mysterious box. -

OMC | Data Export

Ayelet Peer, "Entry on: Goddess Girls (Series, Book 10): Pheme the Gossip by Joan Holub, Suzanne Williams ", peer-reviewed by Lisa Maurice and Susan Deacy. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/395. Entry version as of October 10, 2021. Joan Holub , Suzanne Williams Goddess Girls (Series, Book 10): Pheme the Gossip United States (2013) TAGS: Aphrodite Apollo Ares Artemis Athena/ Athene Eros Helios Heracles / Herakles Hercules Hermes Hydra Medusa Pandora Persephone Phaethon Pheme Poseidon Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Goddess Girls (Series, Book 10): Pheme the Gossip Country of the First Edition United States of America Country/countries of popularity Worldwide Original Language English First Edition Date 2013 Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams, Goddess Girls: Pheme the First Edition Details Gossip. Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division. New York: Aladdin Press, 2013, 272 pp. ISBN 978-1442449374 (paperback) / 978-1-4424-4938-1 (ebook) Alternative histories (Fiction), Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age Genre fiction), Fiction, Humor, Mythological fiction, Novels, School story* Target Audience Children (Older children, 8-12 yrs.) Author of the Entry Ayelet Peer, Bar Ilan University, [email protected] Lisa Maurice, Bar Ilan Univrsity, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood.. -

Goddess Girls: Athena the Brain by Joan Holub & Suzanne Williams Reader’S Theater Adapted by Amy Young

Goddess Girls: Athena the Brain By Joan Holub & Suzanne Williams Reader’s Theater adapted by Amy Young Hero-ology Aphrodite: Here, sit next to me! Athena: Okay, thanks. Hey Aphrodite, who is that green-haired girl in the back? The one that doesn’t shimmer. Aphrodite: Oh, that is Medusa. Her sisters are goddesses, but she is a mortal. Which is why she doesn’t shimmer. Mr. Cyclops: Attention class, attention. Good morning, I’m Mr. Cyclops and this is Beginning Hero-ology. Narrator: Athena gasped. Her teacher was bald, with large, sandaled feet, and had one humongous eye in the middle of his forehead. He was holding a big, bronze soldier’s helmet upside down, like a bowl. Mr. Cyclops: I’ve placed figures of your heroes inside this helmet. Without looking, please choose one and pass the helmet to the person behind you. Over the course of the semester, it’ll be your job to guide the hero you’ve selected on a quest. Narrator: Dionysus, a boy with little horns on top of his head, pulled out a little painted statue of a person about three inches tall. He passed the helmet on to Poseidon, who pulled out another little statue. Medusa: If we don’t like who we get, can we trade? Mr. Cyclops: No trading. Now, you’ll be scored on three skills in my class: Manipulation, disasters, and quick saves. Any more questions? Athena: Do you mean to say that these hero-guys represent real people? And our assignment is to make them do stuff down on Earth? Mr. -

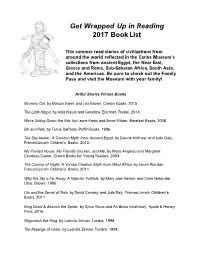

Get Wrapped up in Reading 2017 Book List

Get Wrapped Up in Reading 2017 Book List This summer read stories of civilizations from around the world reflected in the Carlos Museum’s collections from ancient Egypt, the Near East, Greece and Rome, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Americas. Be sure to check out the Family Pass and visit the Museum with your family! Artful Stories Picture Books Mummy Cat, by Marcus Ewert and Lisa Brown. Clarion Books, 2015. The Little Hippo, by Anja Klauss and Geraldine Elschner. Prestel, 2014. We’re Sailing Down the Nile, by Laurie Krebs and Anne Wilson. Barefoot Books, 2008. Bill and Pete, by Tomie DePaola. Puffin Books, 1996. The Star-bearer: A Creation Myth from Ancient Egypt, by Dianne Hofmeyr and Jude Daly. Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2012. My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, and Me, by Maya Angelou and Margaret Courtney-Clarke. Crown Books for Young Readers, 2003. The Coming of Night: A Yoruba Creation Myth from West Africa, by James Riordan. Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2011. Why the Sky is Far Away: A Nigerian Folktale, by Mary Joan Gerson and Carla Golembe. Little, Brown, 1995. Lila and the Secret of Rain, by David Conway and Jude Daly. Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2011. King David & Akavish the Spider, by Sylvia Rouss and Ari Binus (illustrator). Apple & Honey Press, 2015. Gilgamesh the King, by Ludmila Zeman. Tundra, 1998. The Revenge of Ishtar, by Ludmila Zeman. Tundra, 1998. The Last Quest of Gilgamesh, by Ludmila Zeman. Tundra, 1998. I Once Was a Monkey: Stories Buddha Told, by Jeanne M. -

Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams / Goddess Girls (Ages 8-12) Series 1

Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams / Goddess Girls (ages 8-12) series 1 HANDOUT FOR: WHY WRITE ONE BOOK WHEN YOU CAN WRITE A SERIES? Panel: editor Alyson Heller and author Joan Holub #1 Athena the Brain was published in April 2010 by Simon & Schuster / Aladdin Paperbacks. Goddess Girls series is contracted through book #25. This was the first page of our Goddess Girls #1 Athena the Brain book synopsis. Many things changed in the actual book we wrote, but the guts stayed the same. (The Muses did not appear in the series until book #20, there would be no friend named Owlston.) We do a take-off on one or more Greek myths in each book, so instead of bringing a childish lunchbox, Athena brings a keepsake childhood toy horse named Woody, which plays into the Trojan Horse/Odysseus myth takeoff in book #1. Series title: GODDESS GIRLS By Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams Synopsis for Book # 1 Athena the Brain The nine Muses are making up silly songs and rhymes for students to help them remember their locker combinations; Persephone, Aphrodite, and Artemis and are trying out for the Goddess Squad cheer team; and the three Gorgon sisters are stirring up trouble (especially that venomous- tongued bully Medusa). All this can mean only one thing—that Mount Olympus Academy is back in session. Athena, age eleven, has been going to school on Earth at Triton Junior High until now and living at the home of her best friend Pallas, where she was brought up. But when Principal Zeus decides all goddesses belong on Mount Olympus, he orders her to show up at Mount Olympus Academy. -

A Curriculum Guide to the Goddess Girls Series by Joan

A Curriculum Guide to The Goddess Girls Series By Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams Theme 1: Attributes The discussion questions and activities below correlate to the following Common Core State Standards: (RL.3-5.3, 7) (W.3-5.2) (SL.3-5.1). Discussion One: Attributes Make Me Recognizable to Others The goddessgirls and godboys each have attributes that make them unique and recognizable. This discussion examines three kinds of attributes—portable, physical, and mental. Explore these types of attributes with students using the following sets of questions. • QUESTION SET 1: Portable—Sometimes these attributes are things that the goddessgirls and godboys carry. Can you name one of these? What characteristics do these portable attributes symbolize? Possible Answer: Bow and quiver symbolize Artemis as a huntress. The trident, a fish spear, references Poseidon as a god of water. Some goddessgirls and godboys have pets, which are always at their sides. These animals also help us recognize them. Which of the goddessgirls and godboys have animals? Possibly answer: Artemis has her dogs and deer with her. Hades and Cerberus are often together. • QUESTION SET 2: Physical—Attributes may also take the form of physical appearance. Can you name a goddessgirl with a particular physical attribute? Possible Answer: Medusa’s snake hair, Aphrodite’s beauty. How do other goddessgirls, godboys and mortals respond to these physical attributes? What do you think your physical attributes are? How do other students respond to them? • QUESTION SET 3: Mental—Sometimes the attribute is not physical or portable, but, instead, is mental. Can you think of an attribute that is mental? These attributes are usually revealed in action. -

Aphrodite the Diva (Goddess Girls) by Joan Holub

Aphrodite the Diva (Goddess Girls) by Joan Holub Ebook Aphrodite the Diva (Goddess Girls) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Aphrodite the Diva (Goddess Girls) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Age Range:::: 8 - 12 years+++Grade Level:::: 3 - 7+++Lexile Measure:::: 750L +++Series:::: Goddess Girls (Book 6)+++Paperback:::: 220 pages+++Publisher:::: Aladdin; Original edition (August 9, 2011)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1442421002+++ISBN-13:::: 978- 1442421004+++Product Dimensions::::5.1 x 0.9 x 7.6 inches++++++ ISBN10 1442421002 ISBN13 978-1442421 Download here >> Description: In book 6, after a teeny misunderstanding in class, Aphrodite is failing Hero-ology. To raise her grade, she concocts a brilliant plan--an extra- credit project for matchmaking mortals. This brings her face-to-face with fierce competition--an Egyptian goddessgirl named Isis. Now the race is on to see which of them can matchmake Pygmalion--the most annoying boy ever! Will Aphrodite wind up making a passing grade after all? Or will she end up proving shes a diva with more beauty than brains?These classic myths from the Greek pantheon are given a modern twist that contemporary tweens can relate to, from dealing with bullies like Medusa to a first crush on an unlikely boy. Goddess Girls follows four goddesses-in-training - Athena, Persephone, Aphrodite, and Artemis - as they navigate the ins and outs of divine social life at Mount Olympus Academy, where the most priviledged gods and goddesses of the Greek pantheon hone their mythical skills. It was a really good book. -

Ebook Download Aphrodite the Diva Ebook, Epub

APHRODITE THE DIVA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joan Holub,Suzanne Williams,Glen Hanson | 288 pages | 08 Sep 2011 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781442421004 | English | New York, NY, United States Aphrodite the Diva PDF Book When Ares's sister Eris , the goddess of discord and strife, visits on his birthday, she brings a shiny golden apple trophy that reads, "For the fairest. Joan Holub. Log Out. Main series volume 6. Aphrodite the Diva has all the action you can get from Divas. Quick Copy View. Reviews from GoodReads. Get a FREE e-book by joining our mailing list today! Joan Holub Books in English Fantasy. Will Aphrodite ever get the B? She loves the way the characters are described in this book and is now seeking out more Goddess Girls books to read! Add To List. Lists with This Book. This takes her to Egypt and face-to-face with fierce competition—a goddess named Isis. And they have made me even more eager to read each of their books. It is time for the annual Olympic Games at Mount Olympus Academy and the four goddess girls are not happy-especially Artemis, because the Games are for boys only. It only gets better! Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Is this a good book? As in her first book Aphrodite the Beauty, it was clear to me that our personalities were not aligned. See all 15 brand new listings. Who will find love for Pyg? This is because she set a war incident between her hero Paris and the king over a young mortal named Helen. -

Download Artemis the Brave Goddess Girls Pdf Book by Joan Holub

Download Artemis the Brave Goddess Girls pdf ebook by Joan Holub You're readind a review Artemis the Brave Goddess Girls ebook. To get able to download Artemis the Brave Goddess Girls you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Artemis the Brave (Goddess Girls) Age Range: 8 - 12 years Grade Level: 3 - 7 Lexile Measure: 720L Series: Goddess Girls (Book 4) 240 pages Publisher: Aladdin; Reprint edition (December 7, 2010) Language: English ISBN-10: 1416982744 ISBN-13: 978-1416982746 Product Dimensions:5.1 x 0.7 x 7.6 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 14362 kB Description: Artemis may be the goddess of the hunt, but that doesnt mean she always feels brave. Will she find the courage to talk to Orion (the new mortal star at school), to make him see her as more than a pal, and to ace Beast-ology class?The Goddess Girls series by Joan Holub and Suzanne Williams puts a modern spin on classic Greek myths! Follow the ins... Review: There is a lovely new series of books about the Greek goddesses as young girls entitled Goddess Girls. My review of ATHENA THE BRAIN is below. Please note although I havent read this book I can tell you that in my school library this book is checked out constantly. I have multiple copies now and the word of mouth recommendations by the students themselves..