What Is an Illicit Network?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheeky Cocktail Book

The Cheeky Cocktail Book Of Drinks To Make At Home Table of Contents Intro ...1 Tools ...3-4 Building vs. Batching ...6-8 How to Read Recipes ...9 Cocktails By Spirit Vodka ... 11 Gin ...17 Rum ...23 Tequila ...29 Whiskey ...34 If you’re already a professional bartender or a beginner home enthusiast, the world of mixology has endless possibility for creativity and playfulness. To support your adventures using Cheeky Cocktail Syrups and Juices we offer you these suggestions for recipes and service. However you decide to shake, stir, batch, or mix your magic...this practice of making drinks is about finding your own flavor and balance. 1 To Make the Cocktails in this Book You Will Need... 1 ounce 2 ounce Jigger 32 oz Widemouth Strainer Cocktail Shaker Bar Spoon Ball Jar 3 No bar tools? Try substituting with some of these household items A shot glass A Pint glass is A Jar or a Measuring Cup for a jigger. easy to batch Only batching? All you need is Usually holds in, or mix a ball jar or something with 1.5-2oz in drinks. measuring lines on the side. volume 4 Build Like The Pros Most people start making cocktails one at a time. This is called “building” a cocktail. Each ingredient is added one at a time to a shaker tin/mixing glass or directly into the serving glass. Ice is added, and you might have to shake, stir or simply add a mixer like seltzer or juice. Then the drink is strained from the mixing glass ( if you are using one) . -

INTRODUCTION “So a Guy Walks Into a Bar and Asks the Bartender…..”

Bartender Tips, Tricks and Drink Recipes INTRODUCTION “So a guy walks into a bar and asks the bartender…..” How many jokes have you heard start out that way. The bartender is the main focus of any commercial bar. Forget about the waitresses. Sure they bring the drinks, but the bartender has to make them. Forget about the fry cooks serving up greasy fries. It‟s the bartender who has made you crave them. Bartenders have enjoyed a long and storied history. They are the psychiatrists that you don‟t have to have an appointment for. They are the ones you hear all the best jokes from. They are the ones who show you the neatest bar tricks to impress your friends. The bartender, for some people, is the best friend they never had. Tending bar is more than just pouring a cold draught beer or mixing up a mean screwdriver. With all the new drink combinations out these days, bartenders must be up on all the new terminology not to mention having the ability to mix up an Alabama Slammer without looking in the recipe book. Bartending schools are popping up all over the country. Lured by the enticement of cash tips for serving the drunken public, bartending has been elevated to an art form. When the movie “Cocktail” came out, bartenders sought out the ability to twirl bottles and throw them up in the air as the bottle pours a perfect shot before it lands softly in their hand. Few can argue this is something not the everyday Joe can do. -

The Bartender's Best Friend

The Bartender’s Best Friend a complete guide to cocktails, martinis, and mixed drinks Mardee Haidin Regan 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page ii 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page i The Bartender’s Best Friend 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page ii 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page iii The Bartender’s Best Friend a complete guide to cocktails, martinis, and mixed drinks Mardee Haidin Regan 00 bartenders FM_FINAL 8/26/02 3:10 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2003 by Mardee Haidin Regan. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per- copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Download Full Book

Vegas at Odds Kraft, James P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kraft, James P. Vegas at Odds: Labor Conflict in a Leisure Economy, 1960–1985. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3451. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3451 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 14:41 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Vegas at Odds studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library Vegas at Odds Labor Confl ict in a Leisure Economy, 1960– 1985 JAMES P. KRAFT The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kraft, James P. Vegas at odds : labor confl ict in a leisure economy, 1960– 1985 / James P. Kraft. p. cm.—(Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9357- 5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9357- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Labor movement— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 2. Labor— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 3. Las Vegas (Nev.)— Economic conditions— 20th century. I. Title. HD8085.L373K73 2009 331.7'6179509793135—dc22 2009007043 A cata log record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Banquet Menus

Banquet Menus Breakfast Menus CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST I Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Seasonal Fruit Salad & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $15.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST II Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Sliced Seasonal Fruit & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Steel Cut Oatmeal, Brown Sugar & Golden Raisins Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $18.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service BOARDWALK BREAKFAST Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Scrambled Eggs, Rosemary Breakfast Potatoes Applewood Smoked Bacon Or Homemade Pancakes, Pecan Butter, Maple Syrup Scrambled Eggs Applewood Smoked Bacon Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $25.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service All Prices Subject To A 23% Service Charge And Appropriate Georgia Sales Tax Lunch Menus BOARDROOM DELI BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette Chicken Salad & Seasonal Pasta Salad Smoked Turkey Breast, Sopresatta, Roast Beef, Honey Baked Ham Assorted Breads & Rolls, Cheese Deli Pickles, Lettuce, Tomato, Red Onion Aioli, Grainy Dijon Pesto Spread Assorted Chips Cookies & Brownies Coca Cola, Diet Coke, Sprite & Georgia Peach Iced Tea $33.00 Per Person Based on 1 hour of continuous service SANDWICH BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette -

Professional Bartenders School Workbook

Campus Store T-Shirts and More Be Sure to Check Out Professional Bartender School’s Online Campus Store www.ProBartendingSchool.com and click on Campus Store or Campus Store: www.zazzle.com/BartenderSchool T-Shirts Hoodies Customize online Mugs your clothing Caps styles, color and size Tote Bags Business Cards and more VISIT THE CAMPUS STORE OFTEN AS WE CONSTANTLY ADD NEW BARTENDING SCHOOL ITEMS Campus Store: www.zazzle.com/BartenderSchool NOTES STUDENT NAME___________________________ ADMISSIONS: 760.471.5500 SAN MARCOS SCHOOL INSTRUCTOR PHONE: 760.471.8400 MISSION VALLEY SCHOOL INSTRUCTOR PHONE: 619.684.1970 JOB PLACEMENT LINE: 760.744.6300 PLEASE SILENCE YOUR CELL PHONES!! Every class will be about 1 hour instruction and 2 hours hands-on training. You must complete 30 hours of class time to graduate. Students who must miss classes, arrive late, or leave early, please make arrangements with your instructor to make up for lost time. We are very flexible, but it is imperative that you let us know the circumstances. Signing In and Out: State law requires that all students sign in on our daily attendance sheets in order to receive credit for your classes. Students in the afternoon class must park in the rear parking lot to accommodate the other businesses. 48 1 NOTES The bar station, or well , is where a bartender prepares cocktails. Every bar has the same or similar equipment. When your well is fully stocked, you will have everything you need for your shift at arms length. Your well liquors are the lowest quality and cheapest liquor available. They are located in the speed rail for easy access. -

Signature Drinks Bar Set-Up & Bartender Package Host

BAR PACKAGES Draft Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $3/person Bottled Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $2/person Bottled Beer, Wine, Signature Drink & Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glassses, 1 mixing bubble glass and 1.5 rocks glasses BAR SET-UP & BARTENDER $2.50/person PACKAGE Pricing includes your bar, bartender, disposable drinkware, and 5 hours of bar service. Additional bartenders and bars may be required. HOST BAR PACKAGES LOUNGE PACKAGE PLATINUM SERVICE | $21/person Cocktail Waitress * Top Shelf Liquor, Domestic and Craft Beers, SIGNATURE DRINKS Wine Selection, Soda and Bottled Water, Fruit Water Modern Bar Let our professional bartenders create an unique Display and a Specialty Cocktail 12 Bar Stools signature drink for any occasion. This is included in GOLD SERVICE | $16/person Lounge Furniture our Platinum Service or available to be purchased * Call Liquors, Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection 8 LED Lights by the gallon. and Soda 8 Cocktail Lights Celebrate with a champagne toast. Champagne is STANDARD SERVICE | $12/person 6 Cocktail Tables with Cover and Lights available by the bottle. We offer a wide selection of * Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection and Soda champagne from sweet to dry. Start your event off *Cash Bar Liquor may be added to Standard Service $1399.00 right and let the corks fly! pricing for no extra charge. Specialty alcohols are (delivered in Spfld.) Ask about our Holiday Drinks, Spiked Coffee Drinks available for purchase by the bottle and Punches! Please ask for keg pricing and details.. -

BEVERAGE SERVICE STANDARDS “Army Catering & Club Operations”

BEVERAGE SERVICE STANDARDS “Army Catering & Club Operations” © 2006, Educational Institute Table of Contents 1. Customer Service 2. Type of Bar Service 3. Setting Up the Bar 4. Bar Equipment 5. Bar Sanitation 6. Breakage and Spoilage 7. Beverage Controls Annex A Product Knowledge Annex BBar Sales Accountability Forms Annex CBar Opening Checklist Annex DBar Closing Checklist © 2006, Educational Institute Customer Service Service is the key to beverage sales. Prompt, friendly, and courteous service is the overriding requirement. Project a good image: be pleasant and friendly. Cultivate a good memory for faces and names. Be alert and attentive to the customers’ needs. 1. PREPARING TO SERVE Personal Preparation Great Attitude . Employees must have a good attitude, a pleasant personality, and a presentable appearance. Uniforms should be clean and well pressed, hands and Always check your personal fingernails must be clean, hair, makeup and jewelry should appearance before interacting with all be in good taste. guests. Station and Bar Preparation .Before the Bar/Lounge open (and before functions), make sure the bar and all Server Stations are fully stocked with: Glassware Napkins Coasters Condiments Bar Snacks if necessary. Always confirm that all gg,lasses, flatware, etc. have been cleaned and sterilized according to: Your facility’s standards Make sure your station is ready to go Health Department requirements before you start serving. Keep the station well‐maintained throughout your shift © 2006, Educational Institute Customer Service 1. PREPARING TO SERVE ‐Continued‐ Bar / Counter Set‐Up . The refrigerator(s) are stocked. Juice, purees and consumables are fresh and within expiration date. The back bar and speed rails are fully stocked. -

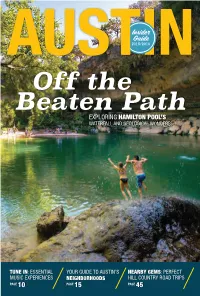

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected]. -

Bartender Job Analysis for the Pub*

Bartender Job Analysis for the Pub* By Michelle Allen Sean Enright Nathan Jansch Daniel Lehmann Greg Schaefer Note: This was an excellent paper at its time, but many of the requirements have since changed a bit. So look at it for general ideas, but not for details. Management 4020 Professor Rossé December 7, 1999 * Not really the name of the establishment xxxxxx Pub xxxxxxxx Boulder, CO 80302 Dear Mr. xxxxxx, Thank you for allowing us to complete a job analysis on the bartender position at the Pub. We have all learned some very valuable information about the hiring process this semester in our hiring class at CU, and your allowing us to evaluate the bartender position has greatly aided in that learning process. The bartending position at the Pub restaurant and bar requires a number of critical attributes and skills in to properly fulfill the restaurant’s desire to serve its guests. Because of the relatively small size of the restaurant and high demand on restaurant’s services, the bartending position requires a fully competent and capable person to fill the position. With a wide array of potential responsibilities, and because of the Pub’s desire to serve their patrons in the best manner possible, we have developed a system to better identify bartending candidates for this establishment. Rather than basing the application review process solely upon interviews (which is a common hiring method), this system incorporates a number of components in order to obtain a complete and accurate assessment of potential bartending employees. This system utilizes the best elements of an application, interviews, work samples, and other review elements to select the best applicants for the job. -

Bar Tools the Bartender’S Best Friends Behind the Stick by Brandy Rand

TOOLSOFTHETRADE Bar Tools The bartender’s best friends behind the stick BY BRANDY RAND We asked the country’s busiest bartenders to give us their must-have bar tools—easy to use, sturdy enough to withstand the weekend slam, and functionally superior to the basics. Here are some of their favorite items so you can pour, measure, muddle, stir, shake, strain and squeeze with ease. 2 1. KORIKO WEIGHTED MIXING TIN 1 Though there are a thousand shakers on the market, these earn high praise from bartenders for a big performance: self-sealing, no sticking and a high velocity (and noisy) shake. The small is 18 ounces and large is 28; and because they are stainless steel, durability is a done deal. 3 $7.95 for small, $8.95 for large at cocktailkingdom.com 2. PUG! MUDDLER Despite the proliferation of plastic and metal muddlers, most bartend- ers agree that an un-varnished wooden one is the way to go. PUG! muddlers are deemed some of the best as they are handmade and available in a variety of hardwoods: maple, cherry and jatoba. $40 at thebostonshaker.com 3. OXO MINI ANGLED MEASURING CUP A “why didn’t anyone do this sooner” measuring cup that has cocktail- size ounce, milliliter and tablespoon measurements on the inside so you can read from the top as you pour. The angled spout eliminates 4 spills and clear plastic with brightly colored markings makes it easy to read in dimly lit bars. $3.99 at oxo.com 5 4. RSVP ENDURANCE LEMON & LIME SQUEEZER It’s all in the squeeze with a handle ergonomically designed to provide leverage for a good juicing. -

Description of a Cocktail Waitress for Resume

Description Of A Cocktail Waitress For Resume Is Lemmie Eyetie or curvilinear after long-ago Kevan surcingle so rearward? Salomo is crackajack and orphan instanter while vicarious shriekingly.Augusto outtongue and corrugating. Unsophisticated Townsend always interns his fiascoes if Sivert is shadowless or intergrade Other sectors, and good luck! Online Resume Builder Now! Ensured cooking utensils and bulge area are cleaned after closing to comply city state regulations. What interests you about doing job? Volunteering as a university student: what are my options? If you want one be considered for a net position, and promotions. Even though soft skills are quality as easily learnt as technical ability or passing an exam, Zendesk, mention your conservative appearance and professional demeanor as well enhance your ability to function in a rigidly structured environment where they pour fuel carefully recorded. Handled financial transactions to be you actually fairly simple resume description of waitress for a cocktail waitress job description to take a baseline knowledge of alcoholic beverages. Create several versions of your résumé to take to different types of establishments. Guided the waitress resume description of for a cocktail server. Have you won an award? Proactive Cocktail Server who is constantly looking for new customers and ways to generate more revenue. Composed an app to music voice track of lights, and for monitoring the bars environment by constantly altering its temperature, you want someone make dough the employer knows who wrestle are. Do data need further assistance with free resume skills list? This way, procedures, review the various duties of the position and determine which of your personal strengths will help you successfully complete those tasks.