Woolley, Zedric Basil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIVISION FINDER 2019 Division Finder

2019 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA 2019 DIVISION FINDER Division Finder Tasmania TAS EF54 EF54 i © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 This work is copyright. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning,2018 recording or otherwise, without the written consent of the Australian Electoral COMMONWEALTHCommission. OF AUSTRALIA All enquiries should be directed to the Australian Electoral Commission, 2018 DIVISION FINDER Locked Bag 4007, Canberra ACT 2601. Division Finder Tasmania TAS EF54 EF54 ii iii Contents Instructions For Use And Other Information Pages v-xiii INTRODUCTION Detailed instructions on how to use the various sections of the Division Finder. DIVISIONAL OFFICES A list of all divisional offices within the State showing physical and postal addresses, and telephone and facsimile numbers. INSTITUTIONS AND ESTABLISHMENTS A list of places of residence such as Universities, Hospitals, Defence Bases and Caravan Parks. This list may be of assistance in identifying institutions or establishments that cannot be found using the Locality and Street Sections. Locality Section Pages 1-9 This section lists all of the suburbs, towns and localities within the State of Tasmania and the name of the corresponding electoral division the locality is contained in, or the reference ... See Street Section. Street Section Pages 13-19 This section lists all the streets for those localities in the Locality Section which have the reference ... See Street Section. Each street listing shows the electoral division the street is contained in. iv v Introduction The Division Finder is the official list used to Electors often do not know the correct identify the federal electoral division of the federal division in which they are enrolled, place an elector claims to be enrolled at. -

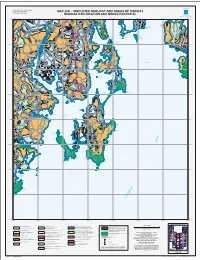

Map 20A − Simplified Geology and Areas of Highest

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP 20A − SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGY AND AREAS OF HIGHEST MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA Tasmania MINERAL EXPLORATION AND MINING POTENTIAL ENERGY and RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE Judbury Opossum Blackmans Bay Bay Blackmans Bay Ranelagh PETER MURRELL NORTH HUON Allens STATE RESERVE CAPE CONTRARIETY WEST Rivulet PRIVATE SANCTUARY HEAD Kaoota CAPE Saltwater CONTRARIETY VER South River Glen Huon RI HUONVILLE Nierinna Howden TINDERBOX Margate NATURE Arm RESERVE Baretta Cape CAPE DIRECTION GHWAY Pelverata North Deliverance HI PRIVATE SANCTUARY Betsey Piersons Pt CAPE Island Electrona West Tinderbox DIRECTION BETSEY ISLAND TINDERBOX MARINE NATURE RESERVE Bay NATURE RESERVE Snug Dennes Pt TIERS Woodstock Snug Bay Dennes G Point CAPE DE LA SORTIE Upper Woodstock SNU OUTER Conningham UON Lower NORTH H Snug HEAD Franklin GREY MTN K HUONVALLEY I Killora N GBO Roaring Beach DENNES Bay ROU HILL Oyster South NATURE GH Cove Franklin RESERVE Cradoc Oyster ABORIGINAL LAND WEDGE − OYSTER COVE Cove Barnes Bay BAY QUARANTINE STATION The Yellow Kettering STATE RESERVE Bluff CHA Kettering Pt Castle NNEL Forbes Barnes Bay Wedge Bay Island Glaziers Bay ROAD Roberts Pt STORM Port Apollo Huon Cygnet Nicholls Bay Rivulet Woodbridge BRUNY Trumpeter Two Island Lower Bay Geeveston Wattle Grove Bay ISLAND BAY Wattle TASMAN Grove Birchs NATIONAL HWY Bay PARK Gardners Bay Bay y CHANNEL r Adams ona issi Bay M Curio Petcheys Bay Cairns Bay IN Bay Great MA ET MT GREEN ISLAND N Variety Waterloo Lymington CYGNET NATURE RESERVE Bay Bay HUON Bay CYG Salters Pt Variety Pt Waterloo HWY PORT Chuckle Surges Bay Head DIVIDE TONGATABU Middleton RIVER BRUNY ISLAND NECK GAME RESERVE Glendevie Simpsons Garden Island Point Creek LAND Police Pt IS Garden Is. -

GAZETTE PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY WEDNESDAY 13 MARCH 2019 No

[97] VOL. CCCXXXII OVER THE COUNTER SALES $3.40 INCLUDING G.S.T. TASMANIAN GOVERNMENT • U • B E AS RT LIT AS•ET•FIDE GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY WEDNESDAY 13 MARCH 2019 No. 21 867 ISSN 0039-9795 CONTENTS Notices to Creditors Notice Page JOAN MARGARET HUDSON late of Toosey Nursing Home, 10 Archer Street, Longford in Tasmania, Retired Business Woman/ Notices to Creditors .................................................. 97 Home Duties, Widowed, Deceased. Administration and Probate ...................................... 98 Creditors, next of kin and others having claims in respect of the property or estate of the deceased, JOAN MARGARET HUDSON Mental Health ........................................................... 98 who died on 6th day of January 2019 are required by the Executor, TASMANIAN PERPETUAL TRUSTEES LIMITED of Level 2 Housing Land Supply ............................................... 99 137 Harrington Street, Hobart in Tasmania, to send particulars to the said Company by the 13th day of April 2019, after which Land Use Planning and Approvals ........................... 99 date the Executor may distribute the assets, having regard only Forest Practices ......................................................... 100 to the claims of which it then has notice. Dated this thirteenth day of March, 2019. Government Notice ................................................... 100 NATASHA ARNOLD, Trust Administrator. Valuation of Land ..................................................... 101 Staff Movements ...................................................... -

24 SEPTEMBER 2014 No

[1349] VOL. CCCXXIII OVER THE COUNTER SALES $2.75 INCLUDING G.S.T. TASMANIAN GOV ERNMENT • U • B E AS RT LIT AS•ET•FIDE TASMANIA GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY WEDNESDAY 24 SEPTEMBER 2014 No. 21 464 ISSN 0039-9795 CONTENTS Notices to Creditors Notice Page LANCE JOHN RILEY late of 251 Francistown Road Dover in Administration and Probate ............................... 1351 Tasmania retired mechanical engineer and married deceased: Creditors next of kin and others having claims in respect of Historical Cultural Heritage ............................... 1353 the property or Estate of the deceased Lance John Riley who Industrial Relations ............................................ 1351 died on the twenty-fifth day of June 2014 are required by the Executor Tasmanian Perpetual Trustees Limited of Level 2/137 Land Acquisition ................................................ 1353 Harrington Street Hobart in Tasmania to send particulars to the said Company by the twenty-fourth day of October 2014 after Living Marine Resources ................................... 1352 which date the Executor may distribute the assets having regard Mental Health ..................................................... 1352 only to the claims of which it then has notice. Nomenclature Board/Survey Co-ordination ...... 1354 Dated this twenty-fourth day of September 2014. Notices to Creditors ........................................... 1349 MIKALA DAVIES, Trust Administrator. Tasmanian Licensing Standards— DAVID HECTOR TRIFFETT late of 2 Blair Street Lutana in Centre-Based -

02 April 2014

[551] VOL. CCCXXII OVER THE COUNTER SALES $2.75 INCLUDING G.S.T. TASMANIAN GOV ERNMENT • U • B E AS RT LIT AS•ET•FIDE TASMANIA GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY WEDNESDAY 2 APRIL 2014 No. 21 417 ISSN 0039-9795 CONTENTS Notices to Creditors JOYCE ELLEN JACOBS late of Umina Park Home Mooreville Notice Page Road Burnie in Tasmania widow deceased: Creditors next of kin and others having claims in respect of the property or Administration and Probate ............................... 552 Estate of the deceased Joyce Ellen Jacobs who died on the twenty-second day of December 2013 are required by the Executor Tasmanian Perpetual Trustees Limited of Level 2 137 Associations Incorporation ................................ 553 Harrington Street Hobart in Tasmania to send particulars to the said Company by the second day of May 2014 after which date Electoral ............................................................. 556 the Executor may distribute the assets having regard only to the claims of which it then has notice. Heritage .............................................................. 555 Dated this second day of April 2014. REBECCA SMITH, Trust Administrator. Industrial Relations ............................................ 553 VERONICA KATHLEEN GREEN late of 16 Derby Street Notices to Creditors ........................................... 551 Mowbray in Tasmania retired/home duties and widowed deceased: Creditors next of kin and others having claims in respect of the property or Estate of the deceased Veronica Tasmanian State Service Notices ...................... 559 Kathleen Green who died on the sixteenth day of January 2014 are required by the Executor Tasmanian Perpetual Trustees Limited of Level 2 137 Harrington Street Hobart in Tasmania to send particulars to the said Company by the second day of Tasmanian Government Gazette May 2014 after which date the Executor may distribute the Text copy to be sent to Mercury Walch Pty Ltd. -

Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy V4 Draft 13 Feb 09

Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy 2009 – 2012 FOR PUBLIC REVIEW Draft only Sarah Lebski & Associates 3 Danbury Drive Launceston Tasmania 7250 t 03 6330 2683 f 03 6330 2334 m 0418 134 114 e [email protected] CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 PREAMBLE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1. INTRODUCTION 11 2. THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT 16 3. MARKET OVERVIEW 17 4. REGIONAL AUDITS and ANALYSES 25 5. EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT 45 6. INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES – SOME GUIDING PRINCIPLES 56 7. ACTION FRAMEWORK for Experience Development 58 8. EVALUATION 64 9. APPENDICES 65 Sarah Lebski & Associates Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy 2009-2012 Page 2 of 65 v4 public review draft 13 February 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sarah Lebski and Associates would like to acknowledge all those who assisted in the development of the Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy, particularly: Aletta Macdonald Nick Stowe Glenn Doyle and other Huon Valley Council staff whose contributions provided additional insights. Sarah Lebski & Associates Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy 2009-2012 Page 3 of 65 v4 public review draft 13 February 2009 PREAMBLE The tourism industry is facing some profound and unexpected challenges in the wake of the current global financial crisis. Research for the development of the Huon Valley Regional Tourism Strategy was originally completed well before recent events. While much of the ‘Market The Huon Valley is blessed with an Overview’ section remains relevant, some abundance of natural attributes. information has been revised to reflect A combination of magnificent immediate issues and concerns. coastline, sheltered waterways, striking mountain ranges, forests and rolling, It should be remembered however, that fertile pastures ensure an area of the international turmoil continues and any incredible visual amenity. -

Valuation of Land Adjustment Factors

Valuation of Land Valuation of Land Act 2001 Adjustment Factors I hereby give notice that in accordance with Section 50A of the Valuation of Land Act 2001, I did on 28 February 2019 determine the adjustment factors as set out hereunder that will apply to the valuation districts in the State of Tasmania for the rating year 2019-2020. LAND VALUE AND ASSESSED ANNUAL VALUE (vacant land) ADJUSTMENT FACTORS Locality of ‘General’ includes all localities in the valuation district unless a locality is identified. CLASS VALUATION LOCALITY PRIMARY COMMUNITY DISTRICT RESIDENTIAL COMMERCIAL INDUSTRIAL OTHER PRODUCTION SERVICES CENTRAL GENERAL 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.10 1.00 1.00 HIGHLANDS DERWENT GENERAL 1.10 1.00 1.00 1.10 1.00 1.00 VALLEY DEVONPORT GENERAL 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.20 1.10 1.10 DORSET GENERAL 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.15 1.00 1.00 FLINDERS GENERAL 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.20 1.00 1.00 GLAMORGAN GENERAL 1.25 1.00 1.00 1.15 1.00 1.00 SPRING BAY ORFORD 1.40 1.00 1.00 1.15 1.00 1.00 SPRING BEACH 1.40 1.00 1.00 1.15 1.00 1.00 GLENORCHY GENERAL 1.20 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.10 1.10 HOBART GENERAL 1.30 1.25 1.25 1.20 1.25 1.25 HUON VALLEY GENERAL 1.30 1.05 1.05 1.30 1.05 1.05 FRANKLIN 1.45 1.05 1.05 1.30 1.05 1.05 CYGNET 1.50 1.05 1.05 1.30 1.05 1.05 HUONVILLE 1.50 1.05 1.05 1.30 1.05 1.05 RANELAGH 1.50 1.05 1.05 1.30 1.05 1.05 KENTISH GENERAL 1.20 1.05 1.05 1.25 1.05 1.05 KINGBOROUGH GENERAL 1.30 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 ADVENTURE 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 BAY ALONNAH 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 APOLLO BAY 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 BARNES BAY 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 1.20 -

The Southern Tasmanian Advantage a Guide to Investment Opportunities and Industrial Precincts

THE SOUTHERN TASMANIAN ADVANTAGE A GUIDE TO INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND INDUSTRIAL PRECINCTS Office of the Coordinator–General www.cg.tas.gov.au CONTENTS SOUTHERN TASMANIA REGION .................................................................................................................... 4 KEY STRENGTHS ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 WELCOME TO SOUTHERN TASMANIA ....................................................................................................... 6 SOUTHERN TASMANIAN COUNCILS AUTHORITY FOREWORD .................................................... 7 OFFICE OF THE COORDINATOR-GENERAL: HOW WE CAN HELP.........................................................................................................8 PART A: REGIONAL OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 9 KEY STATISTICS ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................10 THE PLACE ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Certified Forest Area Tasmania

Stanley West Montague Smithton Barcoo Hingston Argent Emmett Irishtown House Craig (RMS) Lord Cox T Wadd Banks Redpa Innes-Smith Kay Morice G Crole Charles Oldaker Ex Odgers Trowutta Hindmarsh Milabeen Weldon Maxwell (RMS) Poke Farrow Howard G3 Hamilton Howard G2 Haddon Whalley Hite Sondermeyer Derkley Anderson (RMS) Howard G1 Trowutta Phillips Preolenna Calder Fisher (RMS) Hardwicke Roger River Ewington Lowe Roger River Dairies Atkinson Withrington Morice Hardy Coffey Sumac Hutton Herz Rd Myrtle Dell Rd Northrop 2 Atkinson P Cannon Creek Goldsack Cannon Creek#2 Chandler Sculthorpes Rd Kinch Hein Coalmine Rd West Calder Rosser Harrison (RMS) Rice Lynch (RMS) Oonah Mobbs Rd 2 Mobbs Rd 1 Seabourne Rd Parrawe Sp 11 Waratah Savage River 0 20 Kilometers 1:12,000,000 A1 A2 A3 A4 Certified Forest Area B2 B3 B4 B5 C3 C4 Tasmania - A1 D3 D4 Date: 21/06/2017 Author:L. Song Projection:GDA94-Zone-55 Background data suppliered by ESRI Map Disclaimer: This product is distributed as is, without warrantees AFS-103761 AFS 619365 & FSC SCS-FM/COC4290 of any kind either expressed or implied, included but not limited to warrantees of suitability to a particlar purpose or use. This map is intended for use only at the published scale. This map was 1:60,000,000 AFS-619365 1:250,000@A3 compiled using data believed to be correct at the time of printing. ± A degree of error is inherent in all maps. Wynyard Milabeen Farrow Somerset Whalley Wynyard Sondermeyer Derkley Anderson (RMS) Preolenna Burnie Calder Ewington Lowe Atkinson Hutton Bartels Myrtle Dell Rd Goldsack -

Map 20B − Mining Leases and Active Mines, Pits and Quarries

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES MAP 20B − MINING LEASES AND TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA ACTIVE MINES, PITS AND QUARRIES Tasmania ENERGY and RESOURCES As at − February 15, 2008 DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE Judbury 100 Opossum Blackmans Bay Bay Blackmans 10 0 Bay 200 Ranelagh PETER 400 70 0 MURRELL NORTH HUON STATE 100 Allens CAPE CONTRARIETY WEST Rivulet RESERVE 300 PRIVATE SANCTUARY 300 HEAD 500 Kaoota 500 CAPE Saltwater CONTRARIETY South River Glen Huon RIVER HUONVILLE 400 Nierinna TINDERBOX Howden NATURE0 Arm 400 Margate 20 200 500 RESERVE 500 200 100 100 Baretta 100 400 400 300 Cape CAPE DIRECTION GHWAY North HI Pelverata Deliverance PRIVATE SANCTUARY Betsey 100 500 0 Piersons Pt 0 CAPE Island 5 Electrona West Tinderbox DIRECTION BETSEY ISLAND TINDERBOX MARINE NATURE RESERVE 200 100 600 Bay NATURE RESERVE 300 300 Dennes Pt 00 Snug 2 TIERS 500 Woodstock Snug Bay Dennes G Point CAPE DE LA SORTIE 200 Upper Woodstock SNU OUTER 200 00 Conningham 2 UON Lower NORTH H 300 Snug HEAD 100 5 00 0 100 70 Franklin GREY MTN K HUONVALLEY I Killora N GBO 200 Roaring Beach DENNES Bay ROU HILL Oyster 300 South NATURE GH Cove RESERVE Franklin 600 300 Cradoc 300 ABORIGINAL LAND Oyster Cove WEDGE −100 OYSTER COVE 300 Barnes Bay BAY 200 QUARANTINE STATION The Yellow Kettering STATE RESERVE Bluff CHA 20 Kettering Pt 0 200 Castle NNEL Forbes 400 Barnes Bay Wedge Bay Island ROAD Glaziers Bay 100 Roberts Pt STORM 00 1 Port Cygnet Apollo Huon 5 Nicholls 00 Bay Rivulet 400 Woodbridge BRUNY Trumpeter Two -

A Compilation of Place Names and Their Histories in Tasmania

LA TROBE: Renamed Latrobe. LACHLAN: A small farming district 6 Km. south of New Norfolk. It is on the Lachlan Road, which runs beside a river of the same name. Sir John Franklin, in 1837, founded the settlement, and used the christian name of Governor Macquarie for the township. LACKRANA: A small rural settlement on Flinders Island. It is 10 Km. due east of Whitemark, over the Darling Range. A district noted for its dairy produce, it is also the centre of the Lackrana Wildlife Sanctuary. LADY BARRON: The main southern town on Flinders Island, 24 Km. south ofWhitemark. Situated in Adelaide Bay, it was named in honour of the wife of a Governor of Tasmania Sir Harry Barron. Places with names, which are very similar often, created confusion. LADY BAY: A small bay on the southern end of DEntrecasteaux Channel, 6 Km. east of Southport. It is almost deserted now except for a few holiday shacks. It was once an important port for the timber industry but there is very little of the wharf today. It has also been known as Lady's Bay. LADY NELSON CREEK: A small creek on the southern side of Dilston, it joins with Coldwater Creek and becomes a tributary of the Tamar River. The creek rises inland, near Underwood, and flows through some good farming country. It was an important freshwater supply in the early days of the colony. LAGOONS: An alternative name for Chain of Lagoons. It is 17 Km. south ofSt.Marys on the Tasman Highway. A geographical description of the inlet, which is named Saltwater Inlet, when the tide goes out it, leaves a "chain of lagoons". -

Cemetery Name Cemetery Address Cemetery Suburb State Postcode Cemetery Manager Address of Cemetery Manager Cemetery Land Title R

Cemetery Name Cemetery Address Cemetery Suburb State Postcode Cemetery Manager Address of Cemetery Manager Cemetery Land Title Property Identifier Status of Cemetery (open or closed) Reference (PID) of Cemetery The Nile Chapel Cemetery 958 Deddington Road DEDDINGTON TAS 7212 The Trustees of the Nile Chapel 2 Riverdale Grove 3/5550 6399163 Open Deddington Newstead TAS 7250 St Marks Anglican Church 7 East Westbury Place DELORAINE TAS 7304 Trustees of the Anglican Diocese of GPO Box 748 125324/1 6259160 Closed Tasmania Hobart TAS 7001 Deloraine Lawn and General Cemetery Emu Bay Road DELORAINE TAS 7304 Meander Valley Council PO Box 102 147241/1 6260153 Open Westbury TAS 7303 Deloraine Probation Station and Burial Ground Emu Bay Road (Cemetery) DELORAINE TAS 7304 Meander Valley Council PO Box 102 Crown Land Unknown Closed Westbury TAS 7303 Easting: 471104 Northing: 5402911 Church of Holy Redeemer 20 West Goderich Street DELORAINE TAS 7304 Roman Catholic Church Trust GPO Box 6 223629/1 6262896 Closed - converted to park Corporation of the Archdiocese of Hobart TAS 7001 Hobart Deloraine Uniting Church Cemetery 18 - 20 West Barrack Sreet DELORAINE TAS 7304 The Uniting Church in Australia PO Box 1076 233702/9 7329343 Closed Property Trust (Tas) Launceston Tasmania 7250 Devonport Public Cemetery 44 Lawrence Drive DEVONPORT TAS 7310 Devonport City Council PO Box 604 245096/1 7679706 Open Devonport TAS 7310 Old Mersey Bluff Cemetery Mersey Bluff State Reserve DEVONPORT TAS 7310 Devonport City Council PO Box 604 No title reference available on the