Environmental Resource Inventory of the Conservation Element of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pinelqnds of New Jersey

The Pinelqnds of New Jersey A Resource Guide to Public Recreotion opportunities aPRlt t985 ) PUBLIC RECREATION OPPORTUNITIES IN THE NEW JERSEY PINELANDS: A RESOURCE GUIDE (For information on private recreation facilities in the Pinelands, contact the loca1 chamber of commerce or the Division of Travel and Tourism, New Jersey Department of Commerce and Econonic Development. See below for address and telephone number of Travel and Tourism.) The followinq brochures may be obtal-ned from: Division of Parks and forestry State Park Service cN 404 Trenton, NJ 09625 16091 292-2797 o o Bass River State Forest Net Jersey InvLtes You to o Batona Trail Enjoy Its: State Forests, o Belleplain State Forest Parks, Natural Areas, State Campgrounds lfarlnas, HlBtoric Sites & o Hl,storic Batsto llildllfe Managetnent Areas o Island Beach State Park Parvin State Park o Lebanon State Forest Wharton State l'orest The followinq brochures mav be obtained from: Division of Travel and Touriam cN 826 Trenton, Nd, 08625 (6091 292-2470 ' Beach Guide o Marlnas and Boat Basins o Calendar of events o lrinl-Tour cuide o Canpsite Guide o llinter Activities Guide ' Pall Foliage Tours The following brochuree may be obtained fiom: New Jersey Departnent of Environmental Protection office of Natural Lands [ranagement 109 west State St. cN 404 Trenton, NJ 08525 " New Jersey Trails Plan ' The followinq infomatLon mav be obtained from: Green Acres Program cN 404 Trenton, NJ 08625 (6091 292-2455 o outdoor Recreation Plan of New Jerseyr (S5 charge - color publication) * fee charged -

Marriott Princeton Local Attractions Guide 07-2546

Nearby Recreation, Attractions & Activities. Tours Orange Key Tour - Tour of Princeton University; one-hour tours; free of charge and guided by University undergraduate students. Leave from the MacLean House, adjacent to Nassau Hall on the Princeton Univer- sity Campus. Groups should call ahead. (609) 258-3603 Princeton Historical Society - Tours leave from the Bainbridge House at 158 Nassau Street. The tour includes most of the historical sites. (609) 921-6748 RaMar Tours - Private tour service. Driving and walking tours of Princeton University and historic sites as well as contemporary attritions in Princeton. Time allotted to shop if group wishes. Group tour size begins at 8 people. (609) 921-1854 The Art Museum - Group tours available. Tours on Saturday at 2pm. McCormick Hall, Princeton University. (609) 258-3788 Downtown Princeton Historic Nassau Hall – Completed in 1756, Nassau Hall was the largest academic structure in the thirteen colonies. The Battle of Princeton ended when Washington captured Nassau Hall, then serviced as barracks. In 1783 the Hall served as Capital of the United States for 6 months. Its Memorial Hall commemorates the University’s war dead. The Faculty room, a replica of the British House of Commons, serves as a portrait gallery. Bainbridge House – 158 Nassau Street. Museum of changing exhibitions, a library and photo archives. Head- quarters of the Historical Society of Princeton. Open Tuesday through Sunday from Noon to 4 pm. (Jan and Feb – weekends only) (609) 921-6748 Drumthwacket – Stockton Street. Built circa 1834. Official residence of the Governor of New Jersey. Open to the Public Wednesdays from Noon to 2 pm. -

Ceramics Monthly Oct02 Cei10

Ceramics Monthly October 2002 1 editor Ruth C. Butler associate editor Kim Nagorski assistant editor Renee Fairchild assistant editor Sherman Hall proofreader Connie Belcher design Paula John production manager John Wilson production specialist David Houghton advertising manager Steve Hecker advertising assistant Debbie Plummer circulation manager Cleo Eddie circulation administrator Mary E. May publisher Mark Mecklenborg editorial, advertising and circulation offices 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio 43081 USA telephone editorial: (614) 895-4213 advertising: (614) 794-5809 classifieds: (614) 895-4220 circulation: (614) 794-5890 fax (614) 891-8960 e-mail [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] website www.ceramicsmonthly.org Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by The American Ceramic Society, 735 Ceramic Place, Westerville, Ohio 43081; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the editors or The American Ceramic Society. subscription rates: One year $30, two years $57, three years $81. Add $ 18 per year for subscriptions outside North America; for faster delivery, add $12 per year for airmail ($30 total). In Canada, add GST (registration num ber R123994618). change of address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Department, PO Box 6136, Westerville, OH 43086-6136. contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are available on request. Send manuscripts and visual support (slides, transparencies, photographs, drawings, etc.) to Ceramics Monthly, 735 Ceramic PI., Westerville, OH 43081. -

The Story of New Jerseys Ghost Towns and Bog Iron Pdf, Epub, Ebook

IRON IN THE PINES : THE STORY OF NEW JERSEYS GHOST TOWNS AND BOG IRON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Arthur D Pierce | 10 pages | 01 Jul 1984 | Rutgers University Press | 9780813505145 | English | New Brunswick, NJ, United States Iron in the Pines : The Story of New Jerseys Ghost Towns and Bog Iron PDF Book Goes well with Pinelands. The project was a true community effort, launching to prevent the building of a new housing development. Only 10 buildings still stand. Then there were the boat builders, pirates and glassmakers at The Forks of the Mullica River, also the site where Navy hero Stephen Decatur supposedly fired a Jersey-made cannon ball through the wing of the Jersey Devil. Pine Barrens, New Jersey. Chapter Eleven. Purchasing the Howell Furnace site was a logical choice, as it would produce pig iron raw blocks or blocks of iron and cast iron needed to meet demand. Refresh and try again. They are experts in the regulations that protect the Pinelands and provide testimony and analysis to improve enforcement of the Pinelands Protection Act and the Comprehensive Management Plan. Last year, a fire started by carelessly discarded charcoal briquettes burned 1, acres. How to Manage your Online Holdings. Bannack, Montana was once home to a significant gold deposit discovery, made in July of Online User and Order Help. Beth added it Jan 06, The scenic views of the mountain ranges, as well as Ghost Lake down below, are a real treat. To ask other readers questions about Iron in the Pines , please sign up. Fielder , visited the Barrens, then asked the legislature to isolate the area from the rest of the state. -

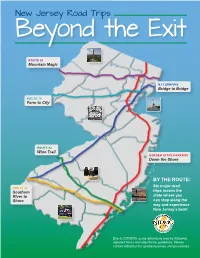

Beyond the Exit

New Jersey Road Trips Beyond the Exit ROUTE 80 Mountain Magic NJ TURNPIKE Bridge to Bridge ROUTE 78 Farm to City ROUTE 42 Wine Trail GARDEN STATE PARKWAY Down the Shore BY THE ROUTE: Six major road ROUTE 40 Southern trips across the River to state where you Shore can stop along the way and experience New Jersey’s best! Due to COVID19, some attractions may be following adjusted hours and attendance guidelines. Please contact attraction for updated policies and procedures. NJ TURNPIKE – Bridge to Bridge 1 PALISADES 8 GROUNDS 9 SIX FLAGS CLIFFS FOR SCULPTURE GREAT ADVENTURE 5 6 1 2 4 3 2 7 10 ADVENTURE NYC SKYLINE PRINCETON AQUARIUM 7 8 9 3 LIBERTY STATE 6 MEADOWLANDS 11 BATTLESHIP PARK/STATUE SPORTS COMPLEX NEW JERSEY 10 OF LIBERTY 11 4 LIBERTY 5 AMERICAN SCIENCE CENTER DREAM 1 PALISADES CLIFFS - The Palisades are among the most dramatic 7 PRINCETON - Princeton is a town in New Jersey, known for the Ivy geologic features in the vicinity of New York City, forming a canyon of the League Princeton University. The campus includes the Collegiate Hudson north of the George Washington Bridge, as well as providing a University Chapel and the broad collection of the Princeton University vista of the Manhattan skyline. They sit in the Newark Basin, a rift basin Art Museum. Other notable sites of the town are the Morven Museum located mostly in New Jersey. & Garden, an 18th-century mansion with period furnishings; Princeton Battlefield State Park, a Revolutionary War site; and the colonial Clarke NYC SKYLINE – Hudson County, NJ offers restaurants and hotels along 2 House Museum which exhibits historic weapons the Hudson River where visitors can view the iconic NYC Skyline – from rooftop dining to walk/ biking promenades. -

The New Jersey Cultural Trust Two Hundred Fifty Qualified

The New Jersey Cultural Trust Two Hundred Fifty Qualified Organizations as of May 18, 2021 Atlantic County Absecon Lighthouse Atlantic City, New Jersey Preserve, interpret and operate Absecon Lighthouse site. Educate the public of its rich history and advocate the successful development of the Lighthouse District located in the South Inlet section of Atlantic City. Atlantic City Arts Foundation Atlantic City, New Jersey The mission of the Atlantic City Arts Foundation is to foster an environment in which diverse arts and culture programs can succeed and enrich the quality of life for residents of and visitors to Atlantic City. Atlantic City Ballet Atlantic City, New Jersey The Atlantic City Ballet is a 501 (c) (3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to bringing the highest quality classical and contemporary dance to audiences of all ages and cultures, with a primary focus on audiences in Southern New Jersey and the surrounding region. AC Ballet programs promote this mission through access to fully-staged performances by a skilled resident company of professional dancers, educational programs suitable for all skill and interest levels, and community outreach initiatives to encourage appreciation of and participation in the art form. Atlantic County Historical Society Somers Point, New Jersey The mission of the Atlantic County Historical Society is to collect and preserve historical materials exemplifying the events, places, and lifestyles of the people of Atlantic County and southern New Jersey, to encourage the study of history and genealogy, and disseminate historical and genealogical information to its members and the general public. Bay Atlantic Symphony Atlantic City, New Jersey The Bay Atlantic Symphony shares and develops love and appreciation for live concert music in the southern New Jersey community through performance and education. -

The New Jersey Pinelands

AN ANNUAL REPORT BY THE PINELANDS PRESERVATION ALLIANCE WWW.PINELANDSALLIANCE.ORG 2018 The New Jersey Pinelands The Pine Barrens is a vast forested area extending across South Jersey’s coastal plain. This important region protects the world’s largest example of pitch pine barrens on Earth and the globally rare pygmy pine forests. One of the largest fresh water aquifers, the Kirkwood-Cohansey, lies underneath its forests and wetlands. The Pine Barrens is home to many rare species, some of which can now only be found here having been extirpated elsewhere. During the 1960’s construction of the world’s largest supersonic jetport and an accompanying city of 250,000 people was proposed for the Pine Barrens. This proposal galvanized citizens, scientists and activists to find a way to permanently protect the Pinelands. In 1978 Congress passed the National Parks and Recreation Act which established the Pinelands National Reserve, our country’s first. In 1979 New Jersey adopted the Pinelands Protection Act. This Act implemented the federal statute, created the Pinelands Commission, and directed the Commission to adopt a Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP) to manage development throughout the region. Many residents do not know that all new development is controlled by the nation’s most innovative regional land use plan. The CMP is designed to preserve the pristine conditions found within the core of the Pinelands while accommodating human use and some growth around the periphery. The Pinelands Commission’s staff of approximately 40 professionals is directed by 15 Commissioners who serve voluntarily. Seven Commissioners are appointed by the Governor with approval of the state Senate, seven by the counties in the Pinelands, and one by the U.S. -

——— Jto 1 1« ^ ^* Om Ft |I|Iil|^L;|^||Llillllll^Ll"Lll: COMMON: \ J *• /, £, ^ R ^**^H Desertod Village of Allaire Bfeatf Iet D ^--'" ^ — P-^

r ' Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Jersey COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Monmouth INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY ^NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) ——— jto 1 1« ^ ^* oM ft |i|iil|^l;|^||llillllll^ll"lll: COMMON: \ j *• /, £, ^ r _ ^**^h Desertod Village of Allaire Bfeatf iet D ^--'" ^ — p-^ AN D^frR HISTORIC: -^*"^*" X^\ \i^-' -• U^V/ ^\ /Howell Works, Monmouth Furnace\ /'x/ hr^ 5^v\ tyfijj^jjjp^ •;:i;:::xiK::.- ••>v'.::::::::::'::*:t:i(iii[P?/^/:f>:J;:;F:::"::^::-::^^>f' ill qq-VriVr-Ty^1'" 7 *%(^x-;-----.v.v.-.-.-.'.v. •-•••-•.•.•.•.•••••.•••.•.•.•-•--•••••-•-•••••-••••••-•-•••••• •••.-.- •.•-:•:••-•-•.••-••--••-•-:•:•:••••-.•:••••-••••;-••:-••••:•:-:••-:. •.-••^^'.•'.•'.•'. t ^<^' . -. - . .-:-:-:-:-:-:-.-:-:-:-:-:?v**:T-:-iP:£>::£:/:'-v:-x .•••^r r; S TJlE.E.T-,Jk,HC>*H.<ltAB.e: R • ^ -/ S£p T . /v U.Botite 52UJX 3 miles southeast of Farminsdale y !~;d ^ 19ft I6 CIT"Y OR TOWNi . ••^-*. —— ,,,,,,r m,,.u,»ro,,4l»1J ___ ,,.,-^^.....— . D) ;•% TONAL t/ • Allaii*G f o-A-«tn v-v,- v-^^w fuJLt^ \ STATE ^ CODE COUNTY: CODE Nk />. • \ C>/ New Jersey 3U Monmoillthx; / ^Y"TTr»"\ \ x 02f? ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS fC/iecfc One) ) THE PUBLIC 25 District Q Building ® Public Public Acquisition: I | Occupied Yes: Restricted n Site Q Structure D P"vate Q ln Process I | Unoccupied *•* Unrestricted Q Object D Both D Being Considered !§C| Preservation work — in progress ' — No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ( I Agricultural |~1 Government 3d Park PI Transportation ^Comments | | Commercial [~1 Industrial f~l Privtite Residence n other (specify) Statc-ownec jp Educational Q Military Q Relicjious historic [~| Entertainment E Museum [~1 Scieritific site ....................... -

The Role of Inlets in Piping Plover Nest Site Selection in New Jersey 1987-2007 45 Christina L

Birds Volume XXXV, Number 3 – December 2008 through February 2009 Changes from the Fiftieth Suppleument of the AOU Checklist 44 Don Freiday The Role of Inlets in Piping Plover Nest Site Selection in New Jersey 1987-2007 45 Christina L. Kisiel The Winter 2008-2009 Incursion of Rough-legged Hawks (Buteo lagopus) in New Jersey 52 Michael Britt WintER 2008 FIELD NotEs 57 50 Years Ago 72 Don Freiday Changes from the Fiftieth Supplement to the AOU Checklist by DON FREIDay n the recent past, “they” split Solitary Vireo into two separate species. The original names created for Blue-headed, Plumbeous, and Cassin’s Vireos. them have been deemed cumbersome by the AOU I “They” split the towhees, separating Rufous-sided committee. Now we have a shot at getting their full Editor, Towhee into Eastern Towhee and Spotted Towhee. names out of our mouths before they disappear into New Jersey Birds “They” seem to exist in part to support field guide the grass again! Don Freiday publishers, who must publish updated guides with Editor, Regional revised names and newly elevated species. Birders Our tanagers are really cardinals: tanager genus Reports often wonder, “Who are ‘They,’ anyway?” Piranga has been moved from the Thraupidae to Scott Barnes “They” are the “American Ornithologists’ Union the Cardinalidae Contributors Committee on Classification and Nomenclature - This change, which for NJ birders affects Summer Michael Britt Don Freiday North and Middle America,” and they have recently Tanager, Scarlet Tanager, and Western Tanager, has Christina L. Kisiel published a new supplement to the Check-list of been expected for several years. -

Calendar of Events $10 Per Child

11 Sun History Kids Club; 10 am – 12 pm & 1:30 - 3:30pm; via EventBrite $5; Day of Ticket $7 (children under 4 Calendar of Events $10 per child. Pre-Register! free). Support the Village! February 11,17, 18, 25 Sat/Sun Village Buildings, Historic Homes, Retail 12 Sat Flea Market, 8 am - 2 pm; The Historic Village at Allaire has an amazing atmosphere and Shops, and Craft Shops OPEN 11 am to 4 pm; $5 Adult, children under 12 free. Allaire Members History Kids Club, Take Home Activity! Make your gorgeous scenery for people to enjoy. Allaire is committed to Children’s activities, early 19th Century trade get free admission! Vendor Space $45 Pre- own Floor Cloth! Visit allairevillage.org to purchase preserving the past and bringing its history alive within the demos, and tours. General Village Admission: registration; $55 Week of Event. Rain Date: 6/13. your kit. Available Feb 1 to Feb 28. Pre-Registration via EventBrite $5; context and legacy of New Jersey’s rich history. Allaire Village Day of Ticket $7 (children under 4 free). 13 Sun History Kids Club; 10 am – 12 pm & 1:30-3:30pm; Inc. is a registered 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, licensed by 13/20 Sat “Sherlock Holmes & the Speckled Band,” a $10 per child. Pre-Register! the State of New Jersey to operate and manage the historic performance by Neill Hartley at the Allaire Chapel; 24 Sat Music Jamboree, 11 am to 4 pm; Local bands property located within Allaire State Park. Allaire Village Inc. 6 & 7:30 pm, $30 per person. -

LIBERTY STATE PARK NOW ALMOST FULLY OPEN Christie Administration Hires Unemployed Workers to Aid the Parks Cleanup Effort

STATE PARKS MAKE GREAT STRIDES TOWARDS POST-SANDY RECOVERY; LIBERTY STATE PARK NOW ALMOST FULLY OPEN Christie Administration Hires Unemployed Workers to Aid the Parks Cleanup Effort (13/P24) JERSEY CITY - The Christie Administration announced today that up to 78 unemployed state residents can be hired by the Department of Environmental Protection to help clean up and restore Sandy storm-damaged state parks through a National Emergency Grant obtained by the state Department of Labor and Workforce Development (DOL). The DEP already has brought on 33 previously unemployed residents through this program who are working at seven state parks, supplementing full-time state work crews on various projects aimed at getting all state parks ready for the upcoming summer tourism season. The DEP is working with DOL on additional hirings. "Getting all of our state parks fully cleaned up and restored for the spring and summer outdoor seasons is a priority for the Christie Administration,'' DEP Commissioner Bob Martin said. "The employees we are hiring through the Department of Labor grants are helping in this important effort at parks that were battered by Superstorm Sandy. They are helping clear debris, repair walkways, restore dunes, and remove trees that are blocking trails and many other important tasks.'' The hirings were announced today during a news conference at Liberty State Park. All of New Jersey's state parks have reopened post-Sandy, including Liberty. Most of Liberty Walk (the Hudson River Walkway), which offers unparalleled views of the Statue of Liberty and the New York skyline, has reopened. The Caven Point section of the park recently re-opened, and some 300 of the park's 343 public use acres now are accessible. -

Wall Township, Incorporated March 7, 1851 by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature, Embraces Approximately Thirty-Two Square Miles in Southern Monmouth County

This in-depth history is kindly offered by Alyce Salmon, Township Historian Emerita. Reproduced by permission. Wall Township, incorporated March 7, 1851 by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature, embraces approximately thirty-two square miles in southern Monmouth County. Wall's ancestors settled first in East Jersey's Shrewsbury Township. This land was already inhabited by the Lenni Lenape, an Algonquian group of Indians (Native Americans) who lived in loosely - knit family groups in the greater Delaware area. Clans managed decisions on marriage and descent, leaving the people to their individual governance. Current research on Lenape life includes books, excavations such as the one at Turkey Swamp and "Pow Wows" presented by the Delaware people themselves. King Charles II of England in 1664 decided to colonize the land he owned between the Hudson and the Delaware Rivers. He dispatched Colonel Robert Nicolls to subdue the Dutch and establish settlements. Nicolls was remarkably successful and named the land "Albania." But before he could return to England, the King granted his brother, James Duke of York, these same lands. The Duke named the tract "Novo Cesarea" or "New Jersey," then gave the territory to court favorites Sir John Carteret and John Lord Berkeley. The result was that two different patent claims were made for the same land, causing title problems which persist to today. New Jersey was divided into East and West Jersey. Upon the death of Berkeley, the land was leased in 1682 by The General Board of Proprietors of the Eastern Division of New Jersey. In 1688, Berkeley's lands were organized as The Council of Proprietors of the Western Division.