The Inquisitorial Functions of Grand Juries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Jury Handbook-For Jurors

Grand Jury Handbook From the Office of Your District Attorney Welcome to The Grand Jury Welcome. You have just assumed a most important role in the administration of justice in your community. Service on the Grand Jury is one way in which you, as a responsible citizen, can directly participate in government. The Grand Jury has the responsibility of safeguarding individuals from ungrounded prosecution while simultaneously protecting the public from crime and criminals. The purpose of this handbook is to help you meet these responsibilities, and be knowledgeable about your duties and limitations. Your service and Copyright April, 2004 acceptance of your duties as a serious commitment to the community is Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia greatly appreciated. Atlanta, Georgia 30303 This handbook was prepared by the staff of the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia and provided to you by your District Attorney’s All rights reserved office to help you fulfill your duties as a Grand Juror. It summarizes the history of the Grand Jury as well as the law and procedures governing the Grand Jury. This handbook will provide you with an overview of the duties, functions and limitations of the Grand Jury. However, the If you have a disability which requires printed materials in alternative formats, legal advice given to you by the court and by me and my assistants will please contact the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia at 404-969-4001. provide a more comprehensive explanation of all of your responsibilities. I sincerely hope you will find the opportunity to participate in the enforcement of the law an enlightening experience. -

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline The following timeline is a very broad overview of the progress of a federal felony case. Many variables can change the speed or course of the case, including settlement negotiations and changes in law. This timeline, however, will hold true in the majority of federal felony cases in the Eastern District of Virginia. Initial appearance: Felony defendants are usually brought to federal court in the custody of federal agents. Usually, the charges against the defendant are in a criminal complaint. The criminal complaint is accompanied by an affidavit that summarizes the evidence against the defendant. At the defendant's first appearance, a defendant appears before a federal magistrate judge. This magistrate judge will preside over the first two or three appearances, but the case will ultimately be referred to a federal district court judge (more on district judges below). The prosecutor appearing for the government is called an "Assistant United States Attorney," or "AUSA." There are no District Attorney's or "DAs" in federal court. The public defender is often called the Assistant Federal Public Defender, or an "AFPD." When a defendant first appears before a magistrate judge, he or she is informed of certain constitutional rights, such as the right to remain silent. The defendant is then asked if her or she can afford counsel. If a defendant cannot afford to hire counsel, he or she is instructed to fill out a financial affidavit. This affidavit is then submitted to the magistrate judge, and, if the defendant qualifies, a public defender or CJA panel counsel is appointed. -

Bills of Attainder and the Formation of the American Takings Clause at the Founding of the Republic Duane L

Campbell Law Review Volume 32 Article 3 Issue 2 Winter 2010 January 2010 Bills of Attainder and the Formation of the American Takings Clause at the Founding of the Republic Duane L. Ostler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Duane L. Ostler, Bills of Attainder and the Formation of the American Takings Clause at the Founding of the Republic, 32 Campbell L. Rev. 227 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Ostler: Bills of Attainder and the Formation of the American Takings Clau Bills of Attainder and the Formation of the American Takings Clause at the Founding of the Republic DUANE L. OSTLER* I. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 228 II. TAKINGS IN AMERICA PRIOR TO 1787 ....................... 228 A. Takings in the Colonies Prior to Independence ....... 228 B. The American Revolution and the Resulting State Constitutions ................................... 231 III. THE HISTORY BEHIND THE BAN ON BILLS OF ATTAINDER AND THE FIFTH AMENDMENT TAKINGS CLAUSE ................... 236 A. Events Leading to the Fifth Amendment .............. 236 B. Madison's Negative Opinion of a Bill of Rights ....... 239 C. Madison's Views on the Best Way to Protect Property Righ ts ................................................ 242 IV. SPECIFIED PROPERTY PROTECTIONS IN THE BODY OF THE CONSTITUTION .......................................... 246 A. Limits Specified in Article 1, Section 10 .............. 246 B. The Ban on Bills of Attainder .................... 248 V. -

Grand Jury Duty in Ohio

A grand jury is an essential part of the legal system. What Is a Grand Jury? In Ohio, a grand jury decides whether the state Thank you for your willingness to help your has good enough reason to bring felony charges fellow citizens by serving as a grand juror. As against a person alleged to have committed a a former prosecuting attorney, I can attest crime. Felonies are serious crimes — ranging that you have been asked to play a vital role from murder, rape, other sexual assaults, and in American democracy. kidnapping to drug offenses, robbery, larceny, financial crimes, arson, and many more. The justice system in America and in Ohio cannot function properly without the The grand jury is an accusatory body. It does not dedication and involvement of its citizens. determine guilt or innocence. The grand jury’s I guarantee that when you come to the end duty is simply to determine whether there is of your time on the grand jury, you will sufficient evidence to make a person face criminal consider this service to have been one of the charges. The grand jury is designed to help the best experiences of your life. state proceed with a fair accusation against a person, while protecting that person from being Our society was founded on the idea of equal charged when there is insufficient evidence. justice under law, and the grand jury is a critical part of that system. Thank you again In Ohio, the grand jury is composed of nine for playing a key role in American justice. -

Bills of Attainder

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 2016 Bills of Attainder Matthew Steilen University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Matthew Steilen, Bills of Attainder, 53 Hous. L. Rev. 767 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE BILLS OF ATTAINDER Matthew Steilen* ABSTRACT What are bills of attainder? The traditional view is that bills of attainder are legislation that punishes an individual without judicial process. The Bill of Attainder Clause in Article I, Section 9 prohibits the Congress from passing such bills. But what about the President? The traditional view would seem to rule out application of the Clause to the President (acting without Congress) and to executive agencies, since neither passes bills. This Article aims to bring historical evidence to bear on the question of the scope of the Bill of Attainder Clause. The argument of the Article is that bills of attainder are best understood as a summary form of legal process, rather than a legislative act. This argument is based on a detailed historical reconstruction of English and early American practices, beginning with a study of the medieval Parliament rolls, year books, and other late medieval English texts, and early modern parliamentary diaries and journals covering the attainders of Elizabeth Barton under Henry VIII and Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford, under Charles I. -

Reforming the Grand Jury Indictment Process

The NCSC Center for Jury Studies is dedicated to facilitating the ability of citizens to fulfill their role within the justice system and enhancing their confidence and satisfaction with jury service by helping judges and court staff improve jury system management. This document was prepared with support from a grant from the State Justice Institute (SJI-18-N-051). The points of view and opinions offered in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Center for State Courts or the State Justice Institute. NCSC Staff: Paula Hannaford-Agor, JD Caisa Royer, JD/PhD Madeline Williams, BS Allison Trochesset, PhD The National Center for State Courts promotes the rule of law and improves the administration of justice in state courts and courts around the world. Copyright 2021 National Center for State Courts 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 ISBN 978-0-89656-316-2 Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 What Is a Grand Jury?............................................................................................2 Special Duties .........................................................................................................3 Size Requirements...................................................................................................4 Term of Service and Quorum Requirements ...........................................................5 Reform -

Student Study Guide Chapter Seven

STUDENT STUDY GUIDE CHAPTER SEVEN Multiple Choice Questions 1. Which of the following contributes to a large amount of public attention for a criminal trial? a. Spectacular crime b. Notorious parties c. Sympathetic victim d. All of the above 2. How are most criminal cases resolved? a. Arraignment b. Plea Bargaining c. Trials d. Appeals 3. Preventive detention has been enacted into law through the ____________. a. Bail Reform Act b. Bail Restoration Act c. Bond Improvement Act d. Bond Policy Act 4. The customary fee for a bail bondsman is ____ of the bail amount. a. 5% b. 10% c. 20% d. 25% 5. Which of the following is not a feature of the grand jury? a. Open to the public b. Advised by a prosecuting attorney c. Sworn to forever secrecy d. Size variation among states 6. If a defendant refuses to enter a plea, the court enters a(n) ____________ plea on his or her behalf. a. guilty b. not guilty c. nolo contendere d. Alford 1 7. Who is responsible for preparing a presentence investigation report? a. Judge b. Jury c. Probation officer d. Corrections officer 8. If a motion for _____________ is granted, one side may have to produce lists of witnesses and witness roles in the case. a. discovery b. severance c. suppression d. summary judgment 9. Which of the following motions may be requested in order to make the defendant appear less culpable? a. Motion for discovery b. Motion in limine c. Motion for change of venue d. Motion to sever 10. Which of the following motions might be requested as the result of excessive pretrial publicity? a. -

Reviving Federal Grand Jury Presentments

Reviving Federal Grand Jury Presentments Ren~e B. Lettow No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury .... In March 1992, Rockwell International pled guilty to five environmental felonies and five misdemeanors connected with its Rocky Flats plant, which manufactured plutonium triggers for nuclear bombs. Prosecutors were elated; the $18.5 million fine was the largest environmental crimes settlement in history. The grand jury, however, had other ideas. The majority of the grand jurors wanted to indict individual officials of both Rockwell and the Department of Energy (DOE), but the prosecutor had resisted individual indictments. So the grand jury, against the prosecutor's will, drew up its own "indictment" and presented it to the judge.2 Its action has confounded legal scholars: what is the status (or even the correct name) of this document? The consternation this question has caused is a measure of the confusion surrounding grand jury law. Although grand juries had considerable independence and were a major avenue for popular participation in the early Republic, their powers have dwindled. Courts have clouded the issue by periodically reasserting the grand jury's traditional powers, then suppressing them again. The Supreme Court has largely been silent. The number of recent articles praising grand juries points to a revival of interest in this institution. Commentators see the grand jury as an antidote to citizens' alienation from their government. One author urges the recreation of administrative grand juries. Another argues for an expansion of the grand jury's reporting function.4 When she was a state's attorney, Attorney General Reno made a point of using grand juries to investigate social ills in Florida.5 1. -

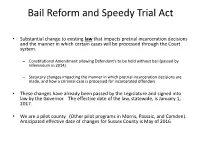

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act

Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Act • Substantial change to existing law that impacts pretrial incarceration decisions and the manner in which certain cases will be processed through the Court system. – Constitutional Amendment allowing Defendant’s to be held without bail (passed by referendum in 2014) – Statutory changes impacting the manner in which pretrial incarceration decisions are made, and how a criminal case is processed for incarcerated offenders • These changes have already been passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the Governor. The effective date of the law, statewide, is January 1, 2017. • We are a pilot county. (Other pilot programs in Morris, Passaic, and Camden). Anticipated effective date of changes for Sussex County is May of 2016. Current Processing of a Criminal Case ARREST/CHARGE SUMMONS WARRANT Central Judicial 1st Appearance/Bail AP not Processing Review (within 72 AP is present Hours) present Plea Hearing Case Resolved Early Case Not Resolved Grand Jury Disposition Presentation Conference Sentencing Arraignment Conference Status Conference Pre-Trial Conference Trial Aspects of Existing System That Will Change • Under the current system, the SCPO is not required, and does not, have an AP present at CJP Court. − CJP Court currently sits 1 day per week and is in session for about 4 hours • Under the current system, for defendants remanded to the jail on a warrant, no weekend appearance is necessary. − This is so because the first appearance/bail review does not need to take place for 72 hours. − Therefore, for a defendant arrested on a Friday, we can legally wait until Monday for the first appearance/bail review Aspects of Existing System That Will Change (Continued) • Under the current system, there are no lengthy testimonial hearings prior to the EDC conference. -

Grand Jury Refonn: a Review of Key Issues

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. U.S. Department of JU5ti,ce •• National Institute of Justice ny Office of Det:eiopmellt, Testillg ami Dissemillatioll lIN II .W , . Grand Jury Refonn: A Review of Key Issues A publication of the National Institute of Justice About the National Institute of Justice Grand Jury Reform: The National Institute of Justice is a research branch of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Institute's A Review of Key Issues mission is to develop knowledge about crime. its causes and control. Priority is given to policy-relevant research that can yield approaches and information State and local agencies can use in preventing and reducing crime. Established in 1979 by the Justice System Improvement Act. :'-JIJ builds upon the foundation laid by the former National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. the first major Federal U.S. Department of Justice 87645 research program on crime and justice. Nat/anal Institute of JUstice Carrying out the mandate assigned by Congress. the National Institute of Justice: This document has been re r d person or orgamzdhon ongln~lI~g~~e~ exact:y as received from the In this document are those of th olnts 0 view or Gil,mons stated • Sponsors research and development to improve and strengthen the criminal justice system and related represent the official POSlllon or pe ,authors and do not necessanly civil justice aspects. with a balanced program of basic and applied research. Jusllce olcles 0 f the National Institute of Permission to reproduce this • Evaluates the effectiveness of federally funded justice improvement programs and identifies programs granted by ~ed matenat has been that promise to be successful if continued or repeated. -

Grand-Jury-Presentations-In-Fatal

State of New Jersey PHILIP D. MURPHY OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL GURBIR S. GREWAL Governor Attorney General DEPARTMENT OF LAW AND PUBLIC SAFETY OFFICE OF PUBLIC INTEGRITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY SHEILA Y. OLIVER THOMAS J. EICHER 25 MARKET STREET Lt. Governor Executive Director PO BOX 085 TRENTON, NJ 08625-0085 OFFICE OF PUBLIC INTEGRITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY (OPIA) STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES TO: Prosecutors and investigators handling fatal police encounter investigations FROM: Thomas J. Eicher, OPIA Executive Director DATE: July 13, 2021 SUBJECT: Grand Jury Presentations in Fatal Police Encounter Investigations At the direction of Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal, the Office of Public Integrity and Accountability (“OPIA”) is establishing these standard operating procedures (“SOP”) for grand jury presentations of investigations involving fatal police encounters. Introduction In December 2019, Attorney General Grewal issued Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive 2019-4, also known as the “Independent Prosecutor Directive,”1 which established a mandatory ten-step process for conducting independent criminal investigations in cases involving fatal police encounters. These SOP cover the preparation and presentation of matters to the grand jury, encompassed in Steps 6 through 10 of the Independent Prosecutor Directive, after the investigative process has been completed. In particular, Step 8 of the Directive addressed the presentation of evidence to a grand jury. Step 8 distinguished between two categories of cases: those where the prosecutor is required to present the matter to the grand jury, and those where the prosecutor is subject to a presumption in favor of presenting to the grand jury, but may decline to do so in certain limited situations. -

The Petit Jury in Virginia, 24 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 24 | Issue 2 Article 18 Fall 9-1-1967 The etP it Jury in Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation The Petit Jury in Virginia, 24 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 366 (1967), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol24/iss2/18 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON AND LEE LAW REVIEW [Vol. XXIV VIRGINIA COMMENT THE PETIT JURY IN VIRGINIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 15.oo The Petit Jury in Virginia .oi Constitutional Provisions .o2 Waiver of Trial by Jury .03 Number .o4 Striking Jurors and Challenges .o5 Qualifications and Exemptions .o5-i Who Is Liable To Serve .05-2 Who Is Disqualified From Service .05-3 Who Is Exempt From Service .o6 Selection of the Jury List .07 Issuance of the Writ of Venire Facias .07-1 General .07-2 List of Names, Occupations, etc. .07-3 Joint Indictments .07-4 Additional Jurors .07-5 Jurors from Another County .07-6 Failure of Juror to Attend .07-7 Irregularities .o8 Compensation 19671 VIRGINIA COMMENT THE PETIT JURY IN VIRGINIA 15.oo THE PETIT JURY IN VIRGINIA .O ConstitutionalProvisions The sixth amendment to the Federal Constitution provides that "in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed....1 While this constitu- tional provision has not been extended to the states,2 the right to a jury trial in criminal cases in Virginia is guaranteed by section 8 of the Bill of Rights of the Virginia Constitution which provides: That in criminal prosecutions a man hath a right to..