A MAGIC BOX and RICHARD BRAUTIGAN by GWEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Non Blondes What's up Abba Medley Mama

4 Non Blondes What's Up Abba Medley Mama Mia, Waterloo Abba Does Your Mother Know Adam Lambert Soaked Adam Lambert What Do You Want From Me Adele Million Years Ago Adele Someone Like You Adele Skyfall Adele Turning Tables Adele Love Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Aladdin A Whole New World Alan Silvestri Forrest Gump Alanis Morissette Ironic Alex Clare I won't Let You Down Alice Cooper Poison Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andreas Bourani Auf Uns Andreas Gabalier Amoi seng ma uns wieder AnnenMayKantenreit Barfuß am Klavier AnnenMayKantenreit Oft Gefragt Audrey Hepburn Moonriver Avicii Addicted To You Avicii The Nights Axwell Ingrosso More Than You Know Barry Manilow When Will I Hold You Again Bastille Pompeii Bastille Weight Of Living Pt2 BeeGees How Deep Is Your Love Beatles Lady Madonna Beatles Something Beatles Michelle Beatles Blackbird Beatles All My Loving Beatles Can't Buy Me Love Beatles Hey Jude Beatles Yesterday Beatles And I Love Her Beatles Help Beatles Let It Be Beatles You've Got To Hide Your Love Away Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Billy Joel Honesty Billy Joel Souvenier Billy Joel She's Always A Woman Billy Joel She's Got a Way Billy Joel Captain Jack Billy Joel Vienna Billy Joel My Life Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel New York State Of Mind Birdy Skinny Love Birdy People Help The People Birdy Words as a Weapon Bob Marley Redemption Song Bob Dylan Knocking On Heaven's Door Bodo -

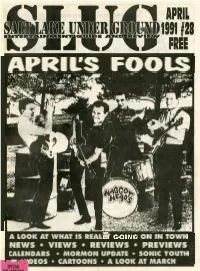

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "Say Aprayer"9-4: - the New Single

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "say aprayer"9-4: - the new single. Your prayers are answered. Breathe's gold debut album All That Jazz delivered three Top 10 singles, two #1 AC tracks, and songwriters David Glasper and Marcus Lillington jumped onto Billboard's list of Top Songwriters of 1989. "Say A Prayer" is the first single from Breathe's much -anticipated new album Peace Of Mind. Produced by Bob Sargeant and Breathe Mixed by Julian Mendelsohn Additional Production and Remix by Daniel Abraham for White Falcon Productions Management: Jonny Too Bad and Paul King RECORDS I990 A&M Record, loc. All rights reserved_ the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A GLANCE * Indicates Tie MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MICHAEL BOLTON JOHNNY GILL MICHAEL BOLTON MATRACA BERG Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) Fairweather Friend (Motown) Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) The Things You Left Undone (RCA) BREATHE QUINCY JONES featuring SIEDAH M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Say A Prayer (A&M) GARRETT Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) LISA STANSFIELD I Don't Go For That ((west/ BASIA HANK WILLIAMS, JR. This Is The Right Time (Arista) Warner Bros.) Until You Come Back To Me (Epic) Man To Man (Warner Bros./Curb) TRACIE SPENCER Save Your Love (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS SAMUELLE M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Unchained Melody (Verve/Polydor) So You Like What You See (Atlantic) Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) 1IrPHIL COLLINS PEBBLES ePHIL COLLINS goGARTH BROOKS Something Happened 1 -

The Democratic Fiction of Richard Brautigan

tile, like an Italian restaurant’s, and the main room doubles as a gallery for MAN UNDERWATER the Clark County Historical Museum, which, on the day of my visit, featured The democratic !ction of Richard Brautigan an exhibit of Vancouver’s newspapers. The shop sells such dreary volumes as By Wes Enzinna For the Love of Farming and Weather of the Paci!c Northwest. The library is situated in a corner of Discussed in this essay: the museum and looks like a living room, with two stuffed chairs and an Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan, by William end table facing a set of bookshelves. Hjortsberg. Counterpoint. 880 pages. $42.50. counterpointpress.com. A whitewashed sign announces that this is #$% &'()#*+(, -*&'('.: ( /%'. 0)&-*1 -*&'('., though there’s no one around except a tall man standing behind one of the chairs, who turns out to be a life-size card- board cutout of the late author Rich- ard Brautigan. Patrons from across the United States have paid twenty-!ve dollars apiece to house their unpub- lished novels here, books with titles like “Autobiography About a Nobody” and “Sterling Silver Cockroaches.” The shelves hold 291 of these cheap vinyl-bound volumes, which are orga- nized into categories according to a schema called the Mayonnaise System: Adventure, Natural World, Street Life, Family, Future, Humor, Love, War and Peace, Meaning of Life, Poetry, Spiri- tuality, Social/Political/Cultural, and All the Rest. Bylines and titles don’t appear on the covers. “The only way to browse the stacks is to choose a category and pick at random,” Barber explains. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

A History of the Communication Company, 1966-1967

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2012 Outrageous Pamphleteers: A History Of The Communication Company, 1966-1967 Evan Edwin Carlson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Carlson, Evan Edwin, "Outrageous Pamphleteers: A History Of The Communication Company, 1966-1967" (2012). Master's Theses. 4188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.cg2e-dkv9 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4188 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Library and Information Science San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Library and Information Science by Evan E. Carlson August 2012 © 2012 Evan E. Carlson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 by Evan E. Carlson APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2012 Dr. Debra Hansen School of Library and Information Science Dr. Judith Weedman School of Library and Information Science Beth Wrenn-Estes School of Library and Information Science ABSTRACT OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 by Evan E. -

Song List 10'S 00'S 90'S 80'S 70'S 50'S & 60'S Jazz

Song List 10’s 00’s 80’s 70’s Song Artist Song Artist Song Artist Song Artist 24K Magic Bruno Mars American Boy Estelle 9 to 5 Dolly Parton April Sun In Cuba Dragon All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone All Night Long Lionel Richie Best of My Love Emotions Bad Guy Billie Eilish Buttons The Pussycat Dolls Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Blame It on The Boogie The Jacksons Be The One Dua Lipa Crazy In Love Beyonce Bette Davis Eyes Kim Carnes Dancing Queen ABBA Blinding Lights The Weeknd Crazy Gnarls Barkley Blister In The Sun Violent Femmes Dreams Fleetwood Mac Break Free Ariana Grande Don’t Know Why Norah Jones Call Me Blondie Eagle Rock Daddy Cool Break My Heart Dua Lipa Don’t Stop The Music Rihanna Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Go Your Own Way Fleetwood Mac Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Forget You Cee Lo Green Do You See What I See Hunters & Collectors Highway To Hell ACDC Can’t Feel My Face The Weeknd Hot & Cold Katy Perry Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Jai Ho Pussycat Dolls Easy Lionel Richie Let's Stay Together Al Green Cake By The Ocean DNCE Love Story Taylor Swift Feeling Hot Hot Hot The Merrymen Mamma Mia ABBA Can’t Stop The Feeling! Justin Timberlake Mr Brightside Killers Flame Trees Cold Chisel Moondance Van Morrison Cheap Thrills Sia Murder On The Dance Floor Sophie Ellis-Bextor Footloose Kenny Loggins Proud Mary Tina Turner Closer The Chainsmokers Party In The U.S.A Miley Cyrus Free Fallin’ Tom Petty Rock With You Michael -

1 United States District Court Southern District of New

Case 1:16-cv-08896-PGG Document 1 Filed 11/16/16 Page 1 of 27 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ERIC MCNATT, Plaintiff, v. COMPLAINT RICHARD PRINCE, BLUM & POE, LLC, BLUM & POE NEW YORK, LLC and JURY TRIAL DEMANDED OCULA LIMITED, Defendants. Plaintiff Eric McNatt (“Mr. McNatt” or “Plaintiff”), by and through his undersigned counsel, for his Complaint (“Complaint”) against defendants Richard Prince (“Mr. Prince”), Blum & Poe, LLC and Blum & Poe New York, LLC (each entity individually or both entities collectively, “Blum & Poe”), and Ocula Limited (“Ocula”) (collectively, “Defendants”) hereby alleges as follows: Nature of Action 1. This is an action for injunctive, monetary and declaratory relief arising from Defendants’ infringement of Mr. McNatt’s exclusive rights in the photographic work entitled “Kim Gordon 1” (the “Copyrighted Photograph”, a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit A). 2. Mr. McNatt is a practiced and acclaimed commercial, editorial and fine art photographer who is the author and copyright owner of the Copyrighted Photograph, which is a black and white portrait capturing the musician Kim Gordon in her home in Northampton, Massachusetts. 1 Case 1:16-cv-08896-PGG Document 1 Filed 11/16/16 Page 2 of 27 3. Defendant Prince, an “appropriation artist” notorious for incorporating the works of others into artworks for which he claims sole authorship, willfully and knowingly and without seeking or receiving permission from Mr. McNatt, copied and reproduced the Copyrighted Photograph as it appeared on an Internet website. Mr. Prince uploaded a digital copy of the Copyrighted Photograph to the social media website Instagram (“Instagram”) using his own Instagram account, accompanied by three captions (the “Infringing Post”). -

College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2011-2012 Student Newspapers 10-31-2011 College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5" (2011). 2011-2012. 15. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012/15 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2011-2012 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ----- - -- -- ~-- ----. -- - - - GOBER 31 2011 VOllJiVlE XCI . ISSUE5 NEW LONDON. CONNEOK:UT Bieber Fever Strikes Again HEATHER HOLMES Biebs the pass because "Mistle- sian to sit down and listen to his 2009. In the course of two years, and will release his forthcom- Christmas album is that Bieber STAFF WRITER toe" is seriously catchy. music in earnest. This, I now re- the now 17-year-old released his ing album, Under the Mistletoe released his first single from Under the Mistletoe, aptly titled Unlike many of Bieber's big- Before this week, 1 had never alize, was a pretty gigantic mis- Iirst EP, My World (platinum in (which will likely go platinum), "Mistletoe," in mid-October. gest hits, it's the verses rather listened to Justin Bieber. Of take. I'm currently making up the U.S.), his first full-length al- on November 1. than the chorus on "Mistletoe" course, I had heard his biggest for lost time. -

Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN CENTER Volume Yll Nos. 3-4 Fall 1968 Last summer Zen Center was at a critical stage in its evolution. The numerous changes resulting from the advent of Zen Mountain Center needed to be consolidated into a satisfactory and stable teaching situation for Suzuki Roshi and the stu· dents. Zen Center found that a number of do0nors were willing to contribute for the specific purpose of freeing the studenrs from the pressures of fund-raising so that they could concentrate on continuing the development of Zen Center and Zen Mountain Center. Nearly S65,000 was donai;. ed. This amount was turned over to Bob and Anna Beck, the previous owners of Tassajara, to cover the next three payments. In return they reduced the final purchase price. Zen Center will now be able to diminish the expe!llse and energy drain of two fund-raising drives a year and direct its funding activities in a more: balanced way. It is hoped that enough will be donated in an annual drive early each fa!ll to secure the following December and March pay ments in advance. However, if you had plamned to make a contribution towards this December's payment, please do. S12,000 in personal loans is already overdue and Sl04,000 is still owed on the Zen Mountain Center land. Why one should help cannot be easily exp[ain· ed. There may not be any personal benefit derived from doing so. In the Diamond Sutra Buddha asks: "What do you think, Subhuti, if a son or daughter of good family had filled this world system of a 1,000 million worlds with the seven precious things, and then gave it as a gift to the Tathagatas, the Arl1ats, t.he Fully Enlightened Ones, would they on the strength of that beget a great heap of merit?" Subhuti replied: "They would, 0 Lord, they would, 0 Well Gone! But if, ot1 the other hand, there were such a thing as a heap of merit, the Tathagata would not have spoken of a heap of merit." The lllmperor of China asked a similar ~ uestion of Bodhidharma: "Since 1 ascended the throne," began the Emperor, "I have erected numeroi<s temples. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

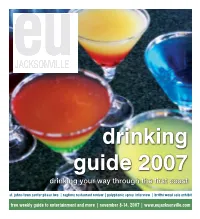

Drinking Your Way Through the First Coast St

drinking guide 2007 drinking your way through the first coast st. johns town center phase two | ragtime restaurant review | polyphonic spree interview | brittni wood solo exhibit free weekly guide to entertainment and more | november 8-14, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 november 8-14, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper COVER PHOTO BY ERIN THURSBY, TAKEN AT TWISTED MARTINI table of contents feature Sea & Sky Spectacular ..........................................................................................................PAGE 13 Town Center - Phase 2 ..........................................................................................................PAGE 14 Town Center - restaurants .....................................................................................................PAGE 15 Cafe Eleven Big Trunk Show ..................................................................................................PAGE 16 Drinking Guide .............................................................................................................. PAGES 20-23 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ............................................................................................ PAGES 6-8 Martian Child (movie review) ...................................................................................................PAGE 6 Fred Claus (movie review) .......................................................................................................PAGE 7 P2 (movie review) ...................................................................................................................PAGE