2000 Year-Old Bogong Moth (Agrotis Infusa)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail Map and Signs

Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Number 73 April 2013 Inside: Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail map and signs Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Patron His Excellency Mr Michael Bryce AM AE Vice Patron Mrs Marlena Jeffery President David Coutts Vice President Barbara Podger Secretary John Connolly Treasurer Marion Jones Public Officer David Coutts General Committee Dennis Ayliffe Glenys Bishop Anne Campbell Lesley Jackman Warwick Wright Talks Convenor Lesley Jackman Membership Secretary Barbara Scott Fronds Committee Margaret Clarke Barbara Podger Anne Rawson Growing Friends Kath Holtzapffel Botanic Art Groups Helen Hinton Photographic Group Graham Brown Social events Jan Finley Exec. Director, ANBG Dr Judy West Post: Friends of ANBG, GPO Box 1777 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Telephone: (02) 6250 9548 (messages) Internet: www.friendsanbg.org.au Email addresses: [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE [email protected] [email protected] Eucalypt Trail map and signs.................................................2 Fronds is published three times a year. We welcome your articles for inclusion in the next Discover eucalypts ................................................................3 issue. Material should be forwarded to the Giant wood moths in the Gardens .........................................4 Fronds Committee by mid-February for the April issue; mid-June for the August issue; Growing Friends ....................................................................6 mid-October -

Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River

November 2017 ACT Heritage Council BACKGROUND INFORMATION Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River Block 700 MAJURA Part Blocks 662, 663, 699, 680, 701, 702, 703, 704 MAJURA Part Blocks 2002, 2091, 2117 JERRABOMBERRA OAKS ESTATE Block 22, Section 2; Block 13, Section 3; Block 4, Section 13; Block 6, Section 13, Block 5, Section 14; Part Block 15, Section 2; Part Block 19, Section 2; Part Block 20, Section 2; Part Block 21, Section 2; Part Block 5, Section 13; Part Block 1, Section 14; Part Block 4, Section 14; Part Block 1, Section 17 At its meeting of 16 November 2017 the ACT Heritage Council decided that the Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River was eligible for registration. The information contained in this report was considered by the ACT Heritage Council in assessing the nomination for the Corroboree Ground and Aboriginal Cultural Area, Queanbeyan River against the heritage significance criteria outlined in s 10 of the Heritage Act 2004. HISTORY The Ngunnawal people are traditionally affiliated with the lands within the Canberra region. In this citation, ‘Aboriginal community’ refers to the Ngunnawal people and other Aboriginal groups within the ACT who draw significance from the place. Whilst the term ‘Aboriginal community’ acknowledges these groups in the ACT, it is recognised that their traditional territories extend outside contemporary borders. These places attest to a rich history of Aboriginal connection to the area. Traditional Aboriginal society in Canberra during the nineteenth century suffered from dramatic depopulation and alienation from traditional land based resources, although some important social institutions like intertribal gatherings and corroborees were retained to a degree at least until the 1860s. -

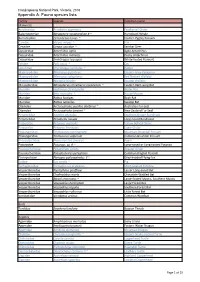

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

The Brain of a Nocturnal Migratory Insect, the Australian Bogong Moth

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/810895; this version posted January 21, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The brain of a nocturnal migratory insect, the Australian Bogong moth Authors: Andrea Adden1, Sara Wibrand1, Keram Pfeiffer2, Eric Warrant1, Stanley Heinze1,3 1 Lund Vision Group, Lund University, Sweden 2 University of Würzburg, Germany 3 NanoLund, Lund University, Sweden Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Every year, millions of Australian Bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) complete an astonishing journey: in spring, they migrate over 1000 km from their breeding grounds to the alpine regions of the Snowy Mountains, where they endure the hot summer in the cool climate of alpine caves. In autumn, the moths return to their breeding grounds, where they mate, lay eggs and die. These moths can use visual cues in combination with the geomagnetic field to guide their flight, but how these cues are processed and integrated in the brain to drive migratory behavior is unknown. To generate an access point for functional studies, we provide a detailed description of the Bogong moth’s brain. Based on immunohistochemical stainings against synapsin and serotonin (5HT), we describe the overall layout as well as the fine structure of all major neuropils, including the regions that have previously been implicated in compass-based navigation. The resulting average brain atlas consists of 3D reconstructions of 25 separate neuropils, comprising the most detailed account of a moth brain to date. -

The Australian Bogong Moth Agrotis Infusa: a Long-Distance Nocturnal Navigator

REVIEW published: 21 April 2016 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00077 The Australian Bogong Moth Agrotis infusa: A Long-Distance Nocturnal Navigator Eric Warrant 1*, Barrie Frost 2, Ken Green 3, Henrik Mouritsen 4, David Dreyer 1, Andrea Adden 1, Kristina Brauburger 1 and Stanley Heinze 1 1 Lund Vision Group, Department of Biology, University of Lund, Lund, Sweden, 2 Department of Psychology, Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada, 3 New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, Jindabyne, NSW, Australia, 4 Institute for Biology and Environmental Sciences, University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany The nocturnal Bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) is an iconic and well-known Australian insect that is also a remarkable nocturnal navigator. Like the Monarch butterflies of North America, Bogong moths make a yearly migration over enormous distances, from southern Queensland, western and northwestern New South Wales (NSW) and western Victoria, to the alpine regions of NSW and Victoria. After emerging from their pupae in early spring, adult Bogong moths embark on a long nocturnal journey towards the Australian Alps, a journey that can take many days or even weeks and cover over 1000 km. Once in the Alps (from the end of September), Bogong moths seek out the shelter of selected and isolated high ridge-top caves and rock crevices (typically at elevations above 1800 m). In hundreds of thousands, moths Edited by: Miriam Liedvogel, line the interior walls of these cool alpine caves where they “hibernate” over the Max Planck Gesellschaft, Germany summer months (referred to as “estivation”). Towards the end of the summer (February Reviewed by: and March), the same individuals that arrived months earlier leave the caves and Christine Merlin, begin their long return trip to their breeding grounds. -

Edible Insects and Other Invertebrates in Australia: Future Prospects

Alan Louey Yen Edible insects and other invertebrates in Australia: future prospects Alan Louey Yen1 At the time of European settlement, the relative importance of insects in the diets of Australian Aborigines varied across the continent, reflecting both the availability of edible insects and of other plants and animals as food. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle adopted by the Australian Aborigines, as well as their understanding of the dangers of overexploitation, meant that entomophagy was a sustainable source of food. Over the last 200 years, entomophagy among Australian Aborigines has decreased because of the increasing adoption of European diets, changed social structures and changes in demography. Entomophagy has not been readily adopted by non-indigenous Australians, although there is an increased interest because of tourism and the development of a boutique cuisine based on indigenous foods (bush tucker). Tourism has adopted the hunter-gatherer model of exploitation in a manner that is probably unsustainable and may result in long-term environmental damage. The need for large numbers of edible insects (not only for the restaurant trade but also as fish bait) has prompted feasibility studies on the commercialization of edible Australian insects. Emphasis has been on the four major groups of edible insects: witjuti grubs (larvae of the moth family Cossidae), bardi grubs (beetle larvae), Bogong moths and honey ants. Many of the edible moth and beetle larvae grow slowly and their larval stages last for two or more years. Attempts at commercialization have been hampered by taxonomic uncertainty of some of the species and the lack of information on their biologies. -

The Brain of a Nocturnal Migratory Insect, the Australian Bogong Moth

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/810895; this version posted October 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. The brain of a nocturnal migratory insect, the Australian Bogong moth Andrea Adden1, Sara Wibrand1, Keram Pfeiffer2, Eric Warrant1, Stanley Heinze1 1 Lund Vision Group, Lund University, Sweden 2 University of Würzburg, Germany Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Every year, millions of Australian Bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) complete an astonishing journey: in spring, they migrate from their breeding grounds to the alpine regions of the Snowy Mountains, where they endure the hot summer in the cool climate of alpine caves. In autumn, the moths return to their breeding grounds, where they mate, lay eggs and die. Each journey can be over 1000 km long and each moth generation completes the entire roundtrip. Without being able to learn any aspect of this journey from experienced individuals, these moths can use visual cues in combination with the geomagnetic field to guide their flight. How these cues are processed and integrated in the brain to drive migratory behaviour is as yet unknown. Equally unanswered is the question of how these insects identify their targets, i.e. specific alpine caves used as aestivation sites over many generations. To generate an access point for functional studies aiming at understanding the neural basis of these insect’s nocturnal migrations, we provide a detailed description of the Bogong moth’s brain. Based on immunohistochemical stainings against synapsin and serotonin (5HT), we describe the overall layout as well as the fine structure of all major neuropils, including all regions that have previously been implicated in compass-based navigation. -

Minds in the Cave: Insect Imagery As Metaphors for Place and Loss

AJE: Australasian Journal of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, Vol. 3, 2013/2014 ASLEC-ANZ ! Minds in the Cave: Insect Imagery as Metaphors for Place and Loss HARRY NANKIN RMIT University 1. The Australian Alps In 1987 I authored a photographic book celebrating the Australian Alps. Its opening paragraph read, in part: Cool, rolling and serene, the High Country . is an assemblage of landforms and living things unlike any other. This crumpled arc of upland, the southeastern elbow of the continent . contains . the only extensive alpine and sub-alpine environments on the Australian mainland . ‘One climbs . and finds, not revelation, but simply range upon range upon range stretching . into distance, a single motif repeating itself to infinity . Climax? . Calm . ’ (Nankin, Range 11). ! Fig. 1 Mount Bogong, Victoria from Range Upon Range: The Australian Alps by Harry Nankin, Algona Publications / Notogaea Press, 1987 A quarter century after these words were published the regions’ serried topography remains unchanged but it no longer connotes serenity or calm. During the summers of 2003 and 2006-7 bushfires of unprecedented ferocity and scale destroyed much of the region’s distinctive old growth sub-alpine snow gum Eucalyptus Pauciflora woodland, a species, which unlike most lowland eucalypts, recovers very slowly and sometimes not at all from fire [Fig. 2]. The extent to which the rising average temperatures and declining snow falls of the last few decades or the more recent drought and heat waves precipitating Harry Nankin: Minds in the Cave: Insect Imagery as Metaphors for Place and Loss these fires were linked to anthropogenic climate change is uncertain. -

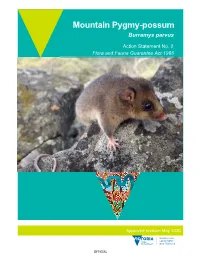

Mountain Pygmy-Possum Action Statement 1

Mountain Pygmy-possum Burramys parvus Action Statement No. 2 Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 Approved revision May 2020 OFFICIAL Cover photo credit Dean Heinze, 2017. Acknowledgment We acknowledge and respect Victorian Traditional Owners as the original custodians of Victoria's land and waters, their unique ability to care for Country and deep spiritual connection to it. We honour Elders past and present whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. We are committed to genuinely partner, and meaningfully engage, with Victoria's Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities to support the protection of Country, the maintenance of spiritual and cultural practices and their broader aspirations in the 21st century and beyond. © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-1-76105-278-1 (pdf/online/MS word) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

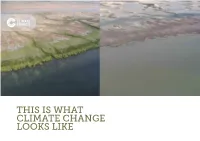

THIS IS WHAT CLIMATE CHANGE LOOKS LIKE Please Note That the Photos of Healthy and Degraded Ecosystems Are Not Necessarily of the Same Locations in All Examples

THIS IS WHAT CLIMATE CHANGE LOOKS LIKE Please note that the photos of healthy and degraded ecosystems are not necessarily of the same locations in all examples. Where possible, we have Thank you for used photos of the same or nearby locations. In other cases, we have chosen photos that depict healthy and degraded examples of the same ecosystem type but from diferent locations. Published by the Climate Council of Australia Limited supporting the ISBN: 978-0-6486793-0-1 (print) 978-0-6486793-1-8 (digital) © Climate Council of Australia Ltd 2019 This work is copyright the Climate Council of Australia Ltd. All material Climate Council. contained in this work is copyright the Climate Council of Australia Ltd except where a third party source is indicated. The Climate Council is an independent, crowd-funded organisation Climate Council of Australia Ltd copyright material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia License. To view a copy of this providing quality information on climate change to the Australian public. license visit http://creativecommons.org.au. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the Climate Council of Australia Ltd copyright material so long as you attribute the Climate Council of Australia Ltd and the authors in the following manner: This is what climate change looks like. Authors: Professor Lesley Hughes, Dr Annika Dean, Professor Will Stefen and Dr Martin Rice. — Cover image: ‘Mangroves before and after marine heatwave’ by Norman Duke. Reproduced with permission. Professor Lesley Hughes Dr Annika Dean This report is printed on 100% recycled paper. Climate Councillor Senior Researcher facebook.com/climatecouncil [email protected] twitter.com/climatecouncil climatecouncil.org.au Professor Will Stefen Dr Martin Rice Climate Councillor Head of Research Preface The word “unprecedented” has been in This report highlights recent examples of these regular use lately. -

Logs and Chips of Eighteen Eucalypt Species from Australia

United States Department of Agriculture Pest Risk Assessment Forest Service of the Importation Into Forest Products Laboratory the United States of General Technical Report Unprocessed Logs and FPL−GTR−137 Chips of Eighteen Eucalypt Species From Australia P. (=Tryphocaria) solida, P. tricuspis; Scolecobrotus westwoodi; Abstract Tessaromma undatum; Zygocera canosa], ghost moths and carpen- The unmitigated pest risk potential for the importation of unproc- terworms [Abantiades latipennis; Aenetus eximius, A. ligniveren, essed logs and chips of 18 species of eucalypts (Eucalyptus amyg- A. paradiseus; Zelotypia stacyi; Endoxyla cinereus (=Xyleutes dalina, E. cloeziana, E. delegatensis, E. diversicolor, E. dunnii, boisduvali), Endoxyla spp. (=Xyleutes spp.)], true powderpost E. globulus, E. grandis, E. nitens, E. obliqua, E. ovata, E. pilularis, beetles (Lyctus brunneus, L. costatus, L. discedens, L. parallelocol- E. regnans, E. saligna, E. sieberi, E. viminalis, Corymbia calo- lis; Minthea rugicollis), false powderpost or auger beetles (Bo- phylla, C. citriodora, and C. maculata) from Australia into the strychopsis jesuita; Mesoxylion collaris; Sinoxylon anale; Xylion United States was assessed by estimating the likelihood and conse- cylindricus; Xylobosca bispinosa; Xylodeleis obsipa, Xylopsocus quences of introduction of representative insects and pathogens of gibbicollis; Xylothrips religiosus; Xylotillus lindi), dampwood concern. Twenty-two individual pest risk assessments were pre- termite (Porotermes adamsoni), giant termite (Mastotermes dar- pared, fifteen dealing with insects and seven with pathogens. The winiensis), drywood termites (Neotermes insularis; Kalotermes selected organisms were representative examples of insects and rufinotum, K. banksiae; Ceratokalotermes spoliator; Glyptotermes pathogens found on foliage, on the bark, in the bark, and in the tuberculatus; Bifiditermes condonensis; Cryptotermes primus, wood of eucalypts. C.