OLD EXETER and the SUGAR RIVER DIGGINGS by Dwayne L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usrwa News: June 2013

USRWA NEWS: JUNE 2013 Coldwater Stream Management in the Upper Sugar River Watershed Text originally written by Tom Beneke, M.S. Water Resources Management, University of Wisconsin-Madison Adapted by Megan Phillips, Executive Director The Upper Sugar River Watershed (USRW) sits nestled in the Driftless Area, which is a biologically and geologically unique region on unglaciated terrain shared by Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Rolling hills, deep valleys, diverse ecosystems, and spring-fed coldwater streams are characteristic of the region. Within the USRW we are fortunate to have several designated trout streams, including the Mt. Vernon Creek State Fishery Area and sections of Deer Creek and Fryes Feeder (continue reading for a partial list of USRW trout streams and the meaning of the various types of designations). These sensitive coldwater habitats are threatened by warming surface temperatures. Last year (2012) volunteer stream monitors recorded surface temperatures at record highs (in the high 80’s/low 90’s (F)), due to the drought and high number of days that topped 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Trout rely on cold water due to their physiology, and their habitat needs to remain within a narrow temperature range to ensure that nutrient uptake does not become too costly. As temperature increases, trout must either minimize swimming effort to conserve energy or gather food resources at a faster rate to keep pace with their increased metabolism. Current climate models predict that trout will be In this Issue: most susceptible to habitat loss during the warmest months of the year - the remaining months will afford them consis- tently habitable temperatures (Lyons et al., 2010, Wiscon- Page 1, 2, 3 - Coldwater sin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts). -

The West Branch Sugar River Year 2017 Assessment Report

May 31, 2020 The West Branch Sugar River Year 2017 Assessment Report A Water Quality Report Prepared by the Bureau of Water Quality to West Branch Sugar River Water Restore Wisconsin’s Watersheds. Quality Monitoring Report, 2017 The Contemporary Condition of the West Branch Sugar River 15 Years After Stream Rehabilitation Dane County, WI WBIC 886100 West Branch Sugar River EGAD #3200-2018-84 Water Quality Bureau Wisconsin DNR 0 | 21 May 31, 2020 The West Branch Sugar River Year 2017 Assessment Report The Contemporary Condition of the West Branch Sugar River 15 Years After Stream Rehabilitation Dane County, WI May 2018 WBIC 886100 Project South_3_CMP17 By James Amrhein, Southern District Water Quality Biologist P a g e 1 | 21 May 31, 2020 The West Branch Sugar River Year 2017 Assessment Report Table of Contents Figures .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Water Quality Monitoring and Planning ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Basin/Watershed Partners ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Rapid Watershed Assessment Sugar River Watershed Wisconsin Illinois

SUGAR RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 Wisconsin Illinois Rapid Watershed Assessment Sugar River Watershed Rapid watershed assessments provide initial estimates of where conservation investments would best address the concerns of landowners, conservation districts, and other community organizations and stakeholders. These assessments help landowners and local leaders set priorities and determine the best actions to achieve their goals. Wisconsin June 2008 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington DC 20250-9410, or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. SUGAR RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 Contents INTRODUCTION 1 ASSESSMENT OF WATERS 5 SOILS 6 DRAINAGE CLASSIFICATION 7 FARMLAND CLASSIFICATION 8 HYDRIC SOILS 9 LAND CAPABILITY CLASSIFICATION 10 RESOURCE CONCERNS 11 PRS PERFORMANCE MEASURES 11 CENSUS AND SOCIAL DATA (RELEVANT) 12 POPULATION ETHNICITY 13 URBAN POPULATION 13 ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPES 14 WATERSHED ASSESSMENT 15 WATERSHED PROJECTS, STUDIES, MONITORING, ETC. 15 FOOTNOTES/BIBLIOGRAPHY 17 SUGAR RIVER WATERSHED (WI) HUC: 07090003 1. INTRODUCTION The Sugar River watershed encompasses nearly 487,000 acres in south central Wisconsin and a small area of north central Illinois. -

![Pecatonica River Water Quality Monitoring Report of Non-Wadable Waters, 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2334/pecatonica-river-water-quality-monitoring-report-of-non-wadable-waters-2015-3482334.webp)

Pecatonica River Water Quality Monitoring Report of Non-Wadable Waters, 2015]

PUBLICMay 31, 2020 REVIEW [PECATONICA DRAFT RIVER WAT– FORER QUALITY PUBLIC MONITORIN COMMENTG REPORT OF NON -WADABLE WATERS, 2015] The Pecatonic a River Targeted A Water Quality Water Quality Assessment of Monitoring Report by the Bureau of Water Quality Non-wadable Waters to Restore and Protect Wisconsin’s Waters. Lafayette and Green Counties WBICs = 889100 and 897800 By James Amrhein and Michael Sorge Southern District, Wisconsin DNR February, 2016 EGAD # 3200-2015-36 Water Quality Bureau Wisconsin DNR Pecatonica River at HWY, 2015. Photo by James Amrhein, Southern District Water Quality Biologist, DNR. Page 1 | 23 May 31, 2020 [PECATONICA RIVER WATER QUALITY MONITORING REPORT OF NON-WADABLE WATERS, 2015] Table of Contents Figures .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Water Quality Monitoring and Planning ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Basin/Watershed Partners ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Native American People in the Lower Sugar River Valley: 12,000 Years Ago to the Present

1 NATIVE AMERICAN PEOPLE IN THE LOWER SUGAR RIVER VALLEY: 12,000 YEARS AGO TO THE PRESENT INTRODUCTION Native American history in the Lower Sugar River Valley (hereinafter referred to as “the valley”) spans nearly 12 millennia from the end of the Pleistocene to the present day. The great story of these people is visible across our landscape in the form of ancient village sites, winter rock shelters, and ancestral burial mounds on prominent bluff tops (Fig. 1, 2 and 3). Additional insights into how these people lived can be seen in the oral traditions and ceremonies of contemporary Native American people. This rich historical record is a palimpsest that allows us to examine and learn from cultures who occupied the area for thousands of years prior to the arrival of the first Europeans. Within this saga are stories of cultures who lived in relative peace and successfully managed their environment meticulously well for centuries, countered by other examples of groups failing under the stress of population pressure, resource depletion, and warfare. The challenges and issues faced by these cultures would be very familiar to us today. We can understand and learn from their experience or ignore it at our peril. If we choose the former, it is important for us to preserve, understand, and respect these places of past endeavor, for by doing so we may well create a foundation for solving some of our contemporary global difficulties. An excellent way to approach an understanding of past environments and the way humans interacted with and altered their surroundings over time is through a close examination of the archaeological remains on the landscape. -

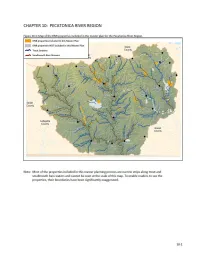

LF0071 Ch10.Pdf

1. OVERVIEW a) Physical Environment Bordered on the north by Military Ridge, this region tilts gently to the south with broad, open plains falling off to narrow, incised valleys. Soils are typically well drained silty and loamy with a silt loam surface over calcareous and non‐calcareous clayey, sandy, or loamy residuum, or over non‐calcareous silty loess. Most areas are over dolostone, limestone, or sandstone bedrock. River bottoms are moderately well drained to poorly drained silty soils with a silt loam surface over calcareous and non‐calcareous silty alluvium or loess. Sandstone and limestone outcroppings are common, though less so than regions north of Military Ridge. b) Land Cover and Use Figure 10.3: Land cover of the Pecatonica River This Planning Region in dominated by agriculture with the majority in Region. row crops (Figure 10.3). With the increasing price of corn and soybeans over the last decade, many pastures, hayfields, and lands that were enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) are being converted to row crops. This large conversion out of permanent vegetation to agricultural uses that expose open soil is also likely to have an adverse effect on water quality of streams in the region. Dry to mesic forests are found along the sides of the narrow valleys with wetlands confined to the riparian zones along larger rivers. Most forests are managed to provide timber products ranging from firewood to sawtimber. c) Terrestrial Habitats This region harbors southern Wisconsin’s best opportunities for prairie management and restoration. In particular, the remnant native and restored prairies, pastures, hay fields, and CRP lands found south of Blue Mounds have some of the highest concentrations of grassland birds remaining in the state. -

Sugar River Master Plan

Sugar River Planning Group Final Master Plan and Footville Wildlife Area Feasibility Study May, 2016 Approved by the Natural Resources Board Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources DNR PUB-LF-083 Cathy Stepp - Secretary Natural Resources Board Terry Hilgenberg, Chair Gregory Kazmierski, Vice Chair Julie Anderson, Secretary William Bruins Preston D. Cole, Dr. Frederick Prehn Gary Zimmer Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 101 S. Webster St. P.O. Box 7921 Madison, Wisconsin 53707-7921 DNR PUB-LF-083 The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunity in its employment, programs, services, and function under an Affirmative Action Plan. If you have any questions, please write to Equal Opportunity Office, Department of Interior, Dane, Green and Rock, D.C. 20240. This publication is available in alternative format (large print, Braille, audio tape, etc.) upon request. Please contact the Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Facilities and Lands at (608) 266- 2135 for more information. Photos (from upper right clockwise) Yahara River (DNR Flickr) White-tailed Deer (DNR Flickr) Bird Watching at Avon Bottoms (DNR Flickr) Pheasant Hunting (DNR Flickr) Master Plan Team Members Plan Acceptance Team Sanjay Olson – Administrator, Lands Division Thomas Hauge - Director, Bureau of Wildlife Management Erin Crain - Director, Bureau of Natural Heritage Conservation Steve Miller - Director, Bureau of Facilities and Lands Dan Schuller - Director, Bureau of Parks and Recreation Paul Cunningham - Director’s designee, Bureau -

USRWA NEWS for Friends of the Upper Sugar River

USRWA NEWS For Friends of the Upper Sugar River The American Pearl Rush: Spring 2011 The Sugar River’s Moment of Fame In This Issue Submitted by George Johnson Page 1- The American Pearl Rush: The Sugar River’s In the 1940s, I often fished for channel catfish in the Sugar River near Du- Moment of Fame rand, Illinois. The preferred bait at that time was “sour” clams and involved a clamming expedition a few days before going fishing. Several misshapen Page 2-The American Pearl pearls were a byproduct of those clam gathering days, but what stayed with me Rush: The Sugar River’s longest was a vague tale of a fortune once being paid in London for a cache of Moment of Fame pearls from the Sugar River. In 2002, I chanced upon a book about pearls and found this sentence: “One shipment made from the Sugar River to London Page 3- USRWA, New Century in September, 1890 contained 93 pearls weighing 28 grains each, for which School, City of Verona Team Up 11,700 pounds was received in payment.” That was equal to $1,300,000 in on Environmental Education today’s dollars. Grant Application The book was a reprint of the 1908 The Book of the Pearl by George Kunz and Page 4- USRWA, New Century William Stevenson. The sentence was part of a section describing an event School, City of Verona Team Up which they called “the pearl excitement”. They described the discovery of on Environmental Education pearls in the Pecatonica River in August, 1889 which overnight turned into Grant Application near hysteria with the populace of river towns descending into the shallows of the nearby stream in search of easy riches. -

CHAPTER 2 - Existing Resource Conditions

DRAFT 10/22/2019 Land & Water Resource Management Plan Rock County Land Conservation Department October 2019 i DRAFT 10/22/2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The development of Rock County’s Land and Water Resource Management Plan, 2019 involved a diverse group of individuals with a wide range of expertise. Their input was critical for the plans development and will continue to be important for achieving the goals of this Plan. Rock County Land Conservation Committee Richard Bostwick, Chair Alan Sweeney, Vice Chair Stephanie Aegerter Wesley Davis Brenton Driscoll Robert Potter James Quade, USDA-FSA Rep. Jeremy Zajac Rock County Land Conservation Department Tom Sweeney, County Conservationist Norman Tadt, Senior Conservation Specialist Chris Murphy, Conservation Specialist III Anne Miller, Conservation Specialist II Duane Collins, Conservation Specialist Mary Kubiak, Clerk Typist III Advisory Work Group Richard Bostwick, Chair Alan Sweeney, Vice Chair Andrew Baker, Planning and Development Dave Rebout, Rebout Farms Bill Barlass, Barlass Jerseys Jane Metcalf, Dairy and Grain Farmer George Andrew, Andrews Maple Hill Farms Patrick Mullooly, Ag Business Representative and Grain Farmer Brian Buenzow, Pheasants Forever Dave Gundlach, NRCS Nick Baker, UWEX Tom Sweeney, LCD Anne Miller, LCD Chris Murphy, LCD Dale Gasser, DNR Lisa Trumble, DATCP Principle Contributors: Authors: Tom Sweeney, County Conservationist and Anne Miller, Conservation Specialist II i DRAFT 10/22/2019 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................... -

Dane County W Ater Quality Plan

Appendix C Update Point Source Inventory and Analysis Dane County Water Quality Plan Dane County Water Prepared by the Capital Area Regional Planning Commission 2017 Capital Area Regional Planning Commission Larry Palm (Chair) Peter McKeever (Vice Chair) Mark Geller (Treasurer) Kris Hampton (Secretary) Steve Arnold Brad Cantrell Lauren Cnare Maureen Crombie Ken Golden Paul Lawrence Ed Minihan David Pfeiffer Caryl Terrell CARPC Staff: Steve Steinhoff, AICP, Deputy Director, and Director of Community and Regional Development Planning Kamran Mesbah, P.E. (ret.) , Deputy Director and Director of Environmental Resources Planning*† Mike Rupiper, P.E., ENV SP, Director of Environmental Resources Planning* Michael Kakuska, Senior Environmental Resources Planner* Sean Higgins, AICP, Senior Community Planner Matt Covert, Community Planner Malissa Dietsch, Community Planner Tony Vandermuss, PE, LEED AP, Environmental Engineer (Principle Author)* Phillip Gaebler, PE, Environmental Engineer *† Greg Orum, PE, Environmental Engineer*† Aaron Krebs, GIS Specialist* Linda Firestone, Administrative Services Manager* The preparation of this document has been financially aided by funds from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. * Project Staff † Former CARPC Employee Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 Organization ................................................................................................................................................. -

Kark's Canoeing and Kayaking Guide to 309 Wisconsin Streams

Kark's Canoeing and Kayaking Guide to 309 Wisconsin Streams By Richard Kark May 2015 Introduction A Badger Stream Love Affair My fascination with rivers started near my hometown of Osage, Iowa on the Cedar River. High school buddies and I fished the river and canoe-camped along its lovely limestone bluffs. In 1969 I graduated from St. Olaf College in Minnesota and soon paddled my first Wisconsin stream. With my college sweetheart I spent three days and two nights canoe-camping from Taylors Falls to Stillwater on the St. Croix River. “Sweet Caroline” by Neil Diamond blared from our transistor radio as we floated this lovely stream which was designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1968. Little did I know I would eventually explore more than 300 other Wisconsin streams. In the late 1970s I was preoccupied by my medical studies in Milwaukee but did find the time to explore some rivers. I recall canoeing the Oconto, Chippewa, Kickapoo, “Illinois Fox,” and West Twin Rivers during those years. Several of us traveled to the Peshtigo River and rafted “Roaring Rapids” with a commercial company. At the time I could not imagine riding this torrent in a canoe. We also rafted Piers Gorge on the Menomonee River. Our guide failed to avoid Volkswagen Rock over Mishicot Falls. We flipped and I experienced the second worst “swim” of my life. Was I deterred from whitewater? Just the opposite, it seems. By the late 1970s I was a practicing physician, but I found time for Wisconsin rivers. In 1979 I signed up for the tandem whitewater clinic run by the River Touring Section of the Sierra Club’s John Muir Chapter. -

Strategic Plan 2014-2018

UPPER SUGAR RIVER WATERSHED ASSOCIATION Aquatic Invasive Species Strategic Plan 2014-2018 Written by Megan Phillips & Wade Moder Funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Dept. of Natural Resouces UPPER SUGAR RIVER WATERSHED ASSOCIATION Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Strategic Plan Table of Contents I. Introduction a. Purpose b. Scope c. Goals II. Background Information a. Summary of Upper Sugar River Watershed and unique plant communities/species threatened by AIS b. Overview of existing AIS in the watershed c. Summary of threats and impacts posed by AIS in Upper Sugar River corridor d. Proposed AIS management strategies III. Fact Sheets a. AIS of concern (high priority) b. AIS of concern (low priority) c. AIS to watch for (not yet present in the watershed) IV. Closing Comments 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Principal Authors: Megan Phillips and Wade Moder, Upper Sugar River Watershed Association Geographic Information Systems Specialist: Wade Moder, Upper Sugar River Watershed Association Advisors/Plant Specialists: Laura MacFarland, River Alliance of Wisconsin Patricia Cicero, Jefferson County Land and Water Conservation Department Cindy Ramseyer, Blue Mounds Area Project Joyce Powers, Botanist and USRWA member Carol Warden, University of Wisconsin/WDNR Monitoring Volunteers/Trainees: Bill Keen Rodd Wangen Jean Kringle Josh Sulman Aaryn Handel Erika Schorenbroch Cassie Anderson Scott Hausmann Anthony Wank Barb Neuser Marty Cieslik This project was funded by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2 INTRODUCTION: In August of 2011 the Upper Sugar River Watershed Association was awarded an Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Education, Prevention and Planning grant from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) to do a variety of education and volunteer promotion efforts to locate and map exotic species in the watershed, raise awareness and reduce new introduction and spread of AIS in the basin.