How Baseball Informs Legal Argument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUGS Sports Actual Practice Or Game Situations

Contents 04 — Baseball & Softball Pitching Machines 27 — Accessories 28 — Packages 32 — Batting Cage Nets 35 — Batting Cage Frames NEW Low Cost, High Quality Batting Cage 36 — Free-Standing Cages Netting for Baseball and Softball: Page 32 38 — Hitting Tee Collection 41 — Protective Screens 46 — Sports Radar 47 — Backyard Bullpen 48 — Practice Baseballs & Softballs 50 — Football, Lacrosse, Soccer and Cricket ! WARNING The photographs and pictures shown in this catalog were chosen for marketing purposes only and therefore are not intended to depict © 2017 JUGS Sports actual practice or game situations. YOU MUST READ THE PRODUCT INFORMATION AND SAFETY SIGNS BEFORE USING JUGS PRODUCTS. TRADEMARKS AND REGISTERED TRADEMARKS • The following are registered trademarks of JUGS Sports: MVP® Baseball Pitching Machine, Lite-Flite® Machine, Lite-Flite®, Small-Ball® Pitching Machine, Sting-Free®, Pearl®, Softie®, Complete Practice Travel Screen®, Short-Toss®, Quick-Snap®, Seven Footer®, Instant Screen®, Small-Ball® Instant Protective Screen, Small-Ball® , Instant Backstop®, Multi-Sport Instant Cage®, Dial-A-Pitch® , JUGS®, JUGS Sports®, Backyard Bullpen®, BP®2, BP®3, Hit at Home® and the color blue for pitching machines. • The following are trademarks of JUGS Sports: Changeup Super Softball™ Pitching Machine, Super Softball™ Pitching Machine, 101™ Baseball Pitching Machine, Combo Pitching Machine™, Jr.™ Pitching Machine, Toss™ Machine, Football Passing Machine™, Field General™ Football Machine, Soccer Machine™, Dial-A-Speed™, Select-A-Pitch™, Pitching -

Base Ball En Ban B

,,. , Vol. 57-No. 2 Philadelphia, March 18, 1911 Price 5 Cents President Johnson, of the American League, in an Open Letter to the Press, Tells of Twentieth Century Advance of the National Game, and the Chief Factors in That Wonderful Progress and Expansion. SPECIAL TO "SPORTING LIFE." race and the same collection of players in an HICAGO, 111., March 13. President exhibition event in attracting base ball en Ban B. Johnson, of the American thusiasts. An instance in 1910 will serve to League, is once more on duty in illustrate the point I make. At the close C the Fisher Building, following the of the American League race last Fall a funeral of his venerable father. While in Cincinnati President John team composed of Cobb, the champion bats son held a conference with Chair man of the year; Walsh, Speaker, White, man Herrmann, of the National Commission, Stahl, and the pick of the Washington Club, relative to action that should be taken to under Manager McAleer©s direction, engaged prevent Kentucky bookmakers from making in a series with the champion Athletics at a slate on American and National League Philadelphia during the week preceding the pennant races. The upshot is stated as fol opening game of the World©s Series. The lows by President Johnson: ©©There is no attendance, while remunerative, was not as need for our acting, for the newspapers vir large as that team of stars would have at tually have killed the plan with their criti tracted had it represented Washington in the cism.- If the promoters of the gambling syn American League. -

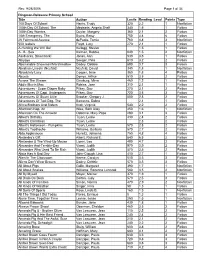

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points

Rev. 9/28/2006 Page 1 of 34 Dingman-Delaware Primary School Title Author Lexile Reading Level Points Type 100 Days Of School Harris, Trudy 320 2.2 1 Nonfiction 100th Day Of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 340 1.5 1 Fiction 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 360 2.1 2 Fiction 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 750 4.4 6 Fiction 26 Fairmount Avenue dePaola, Tomie 760 4.8 3 Nonfiction 500 Isabels Floyd, Lucy 270 2.1 1 Fiction A-Hunting We Will Go! Kellogg, Steven 1.5 1 Fiction A...B...Sea Kalman, Bobbie 640 1.5 2 Nonfiction Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 3.5 1 Fiction Abiyoyo Seeger, Pete 610 3.2 2 Fiction Abominable Snowman/Marshmallow Dadey, Debbie 690 3.7 3 Fiction Abraham Lincoln (Neufeld) Neufeld, David 340 1.8 1 Nonfiction Absolutely Lucy Cooper, Ilene 360 1.8 4 Fiction Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 3.5 2 Fiction Across The Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 460 1.2 1 Fiction Addie Meets Max Robins, Joan 310 2.1 1 Fiction Adventures - Super Diaper Baby Pilkey, Dav 270 3.1 2 Fiction Adventures Of Capt. Underpants Pilkey, Dav 720 3.5 3 Fiction Adventures Of Stuart Little Brooker, Gregory J. 500 2.8 2 Fiction Adventures Of Taxi Dog, The Barracca, Debra 2.1 1 Fiction Africa Brothers And Sisters Kroll, Virginia 540 2.2 2 Fiction Afternoon Nap, An Wise, Beth Alley 450 1.6 1 Nonfiction Afternoon On The Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 290 3.1 3 Fiction Albert's Birthday Tryon, Leslie 430 2.4 2 Fiction Albert's Christmas Tryon, Leslie 2.3 2 Fiction Albert's Halloween - Pumpkins Tryon, Leslie 570 2.8 2 Fiction Albert's Toothache Williams, Barbara 570 2.7 2 Fiction Aldo Applesauce Hurwitz, Johanna 750 4.8 4 Fiction Alejandro's Gift Albert, Richard E. -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections

Rocky Mountain Classical Christian Schools Speech Meet Official Selections Sixth Grade Sixth Grade: Poetry 3 anyone lived in a pretty how town 3 At Breakfast Time 5 The Ballad of William Sycamore 6 The Bells 8 Beowulf, an excerpt 11 The Blind Men and the Elephant 14 The Builders 15 Casey at the Bat 16 Castor Oil 18 The Charge of the Light Brigade 19 The Children’s Hour 20 Christ and the Little Ones 21 Columbus 22 The Country Mouse and the City Mouse 23 The Cross Was His Own 25 Daniel Boone 26 The Destruction of Sennacherib 27 The Dreams 28 Drop a Pebble in the Water 29 The Dying Father 30 Excelsior 32 Father William (also known as The Old Man's Complaints. And how he gained them.) 33 Hiawatha’s Childhood 34 The House with Nobody in It 36 How Do You Tackle Your Work? 37 The Fish 38 I Hear America Singing 39 If 39 If Jesus Came to Your House 40 In Times Like These 41 The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers 42 Live Christmas Every Day 43 The Lost Purse 44 Ma and the Auto 45 Mending Wall 46 Mother’s Glasses 48 Mother’s Ugly Hands 49 The Naming Of Cats 50 Nathan Hale 51 On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer 53 Partridge Time 54 Peace Hymn of the Republic 55 Problem Child 56 A Psalm of Life 57 The Real Successes 60 Rereading Frost 62 The Sandpiper 63 Sheridan’s Ride 64 The Singer’s Revenge 66 Solitude 67 Song 68 Sonnet XVIII 69 Sonnet XIX 70 Sonnet XXX 71 Sonnet XXXVI 72 Sonnet CXVI 73 Sonnet CXXXVIII 74 The Spider and the Fly 75 Spring (from In Memoriam) 77 The Star-Spangled Banner 79 The Story of Albrecht Dürer 80 Thanksgiving 82 The Touch of the -

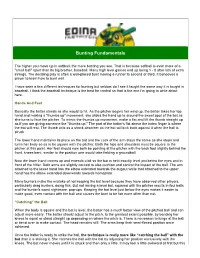

Bunting Fundamentals

Bunting Fundamentals The higher you move up in softball, the more bunting you see. That is because softball is even more of a "small ball" sport than its big brother, baseball. Many high level games end up being 1 - 0 after lots of extra innings. The deciding play is often a well-placed bunt moving a runner to second or third. It behooves a player to learn how to bunt well. I have seen a few different techniques for bunting but seldom do I see it taught the same way it is taught in baseball. I think the baseball technique is the best for control so that is the one I'm going to write about here. Hands And Feet Basically the batter stands as she would to hit. As the pitcher begins her wind up, the batter takes her top hand and making a "thumbs up" movement, she slides the hand up to around the sweet spot of the bat as she turns to face the pitcher. To mimic the thumbs up movement, make a fist and lift the thumb straight up as if you are giving someone the "thumbs up." The part of the batter's fist above the index finger is where the bat will rest. The thumb acts as a shock absorber as the bat will kick back against it when the ball is struck. The lower hand maintains its place on the bat and the cock of the arm stays the same as she steps and turns her body so as to be square with the pitcher. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

2015 Event Information

2015 Event Information Event Partners www.BaseballCoachesClinic.com January 2015 Dear Coach, We are excited to welcome you as we celebrate our twelfth year of the Mohegan Sun World Baseball Coaches’ Convention. Beginning with the first clinic in 2004, we have sought to provide you with the very best in coaching education. We want this clinic to be something special and we have spent considerable time securing the best clinicians and designing a curriculum that addresses all levels of play and a range of coaching areas. Each year, we seek to improve your clinic experience and this year we've made two major improvements: we've redesigned the event layout to improve traffic flow and we are introducing an event App for your smartphone or tablet to put critical clinic information at your fingertips. We believe our clinic is more than just three days of coaching instruction; it is a chance to exchange ideas and learn from each other. Our convention staff, exhibitors and guest speakers will be available to you throughout the clinic. Please don’t hesitate to introduce yourself, ask a question or provide your own perspective on the game. A special thanks goes to the staff and management of the Mohegan Sun - our title sponsor - who have welcomed us and allowed us to use their outstanding facilities and amenities. We also thank our other sponsors for their important support, including: Extra Innings, Rawlings, On Deck Sports, Hitting Guru 3D, Baseball Heaven, Louisville Slugger, Baseball America, Club Diamond Nation, Lux Bond & Green, Jaypro Sports, The Coaches Insider and Geno’s Fastbreak Restaurant. -

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature As Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature as Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012 List compiled by: Michelle Faught, Aldine ISD, Sheri McDonald, Conroe ISD, Sally Rasch, Aldine ISD, Jessica Scheller, Aldine ISD. April 2012 2 Enhancing the Curriculum with Children’s Literature Children’s literature is valuable in the classroom for numerous instructional purposes across grade levels and subject areas. The purpose of this bibliography is to assist educators in selecting books for students or teachers that meet a variety of curriculum needs. In creating this handout, book titles have been listed under a skill category most representative of the picture book’s story line and the author’s strengths. Many times books will meet the requirements of additional objectives of subject areas. Summaries have been included to describe the stories, and often were taken directly from the CIP information. Please note that you may find some of these titles out of print or difficult to locate. The handout is a guide that will hopefully help all libraries/schools with current and/or dated collections. To assist in your lesson planning, a subjective rating system was given for each book: “A” for all ages, “Y for younger students, and “O” for older students. Choose books from the list that you will feel comfortable reading to your students. Remember that not every story time needs to be a teachable moment, so you may choose to use some of the books listed for pure enjoyment. The benefits of using children’s picture books in the instructional setting are endless. The interesting formats of children’s picture books can be an excellent source of information, help students to understand vocabulary words in different contest areas, motivate students to learn, and provide models for research and writing. -

Weber Writes 2010 Weber Writes 2010 I 2

1 Weber Writes 2010 2 Weber Writes 2010 i Table of Contents Foreword .............................................................................................ii Research and Argument .................................................................1 Maryam Ahmad, “France’s War on Religious Garb” .............3 Liz Borg, “When it Comes to Sex and Jr.” ..............................9 Brandi Christensen, “Communism and Civil War”............. 13 Casey Crossley, “Integrity Deficit: The Scarcity of Honor in Cable News” .................................................... 18 Chris Cullen, “The Power of Misconception” .................... 28 Chase Dickinson, “Are Kids on a One-Way Path to Violence?” ............................................................ 35 Melissa Healy, “Lessons from a Lionfish”............................ 39 Feliciana Lopez, “The Low Cost of Always Low Prices” .......................................................... 43 Sarah Lundquist, “Women in the Military: The Army Combat Exclusion” ............................................... 48 Jamie Baer Mercado, “Radical or Rational?” ........................ 57 Olivia Newman, “Science Friction” ...................................... 63 Jason Nightengale, “Cheating and Steroids” ........................ 68 Paulette Padilla, “Grotesque Entertainment: Should It Be Legal?” ........................................................ 76 Dolly Palmer, “The Social and Physiological Separation of Space” ....................................................... 82 Michael Porter, “Are -

Classics Lists

Classics Lists To enhance your experience with Leadership Education, click on the following: • This Week In History: Kidschool Resources and Top Picks from Rachel DeMille • Free downloads from TJEd.org • The TJEdOnline Community • The Leadership Library Product Store • The TJEd Online Forum *Affiliate links: While your price remains the same, any purchases made on Amazon.com that originate from these links result in tjed.org receiving a portion of the proceeds. So if you’re planning to shop Amazon, please start here! Thanks for supporting TJEd. 2 o one can deny the value of a great idea well-communicated. The inspiration, innovation and ingenuity inherent in great ideas elevate those who study them. N Great ideas are most effectively learned directly from the greatest thinkers, historians, artists, philosophers and prophets, and their original works. Great works inspire greatness, just as mediocre or poor works usually inspire mediocre and poor achievement. The great accomplishments of humanity are the key to quality education. A “classic” is a work — be it literature, music, art, etc. — that’s worth returning to over and over because you get more from it each time. There are many popular lists of classics; and each person, as he or she logs time with the great works of history will hopefully develop his or her own personal classics list. Family Education Reading List: To edify your family culture of life-long learning, we especially recommend the following titles. Each of these exemplifies a family that is unified in their vision and application of the principles of Leadership Education. Plus, they’re fun to read together! • Little Britches, Moody (this whole series is fabulous) • Farmer Boy, Wilder (again–the whole series has wonderful lessons to shape and heal families) • Laddie, Stratton-Porter (starts a little slow, but the treasures in this book are soooo worth it!) • Cheaper by the Dozen, Gilbreth (energetic and parent-inspired excellence!) 3 Classics for Young Children & Family Reading There is treasure in the shared experience of family reading. -

Bi-Weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020

INTEGRITY IN SPORT Bi-weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020 Photos International Olympic Committee INTERPOL is not responsible for the content of these articles. The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not represent the views of INTERPOL or its employees. INTERPOL Integrity in Sport Bi-Weekly Bulletin 17-30 March 2020 INVESTIGATIONS Pakistan PCB Charges Umar Akmal for Breaching Anti-Corruption Code Controversial Pakistan batsman Umar Akmal has been charged on Friday for two separate breaches of the Pakistan Cricket Board's Anti-Corruption Code. Umar, who was provisionally suspended on February 20 and barred from playing for his franchise, Quetta Gladiators in the Pakistan Super League, has been charged for failing to disclose corrupt approaches to the PCB Vigilance and Security Department (without unnecessary delay). If found guilty, Akmal could be banned from all forms of cricket for anywhere between six months and life. He was issued the charge sheet on March 17 and has been given time to respond until March 31. This was a breach under 2.4.4 for PCB's anti- corruption code. A Troubled Career Umar, 29, has had a chequered career since making his debut in August, 2009 and has since just managed to play 16 Tests, 121 ODIs and 84 T20 internationals for his country despite making a century on Test debut. His last appearance came in last October during a home T20 series against Sri Lanka and before that he also played in the March- April, 2019 one-day series against Australia in the UAE.