Jennifer Worth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

70 NHS Years: a Celebration of 70 Influential Nurses and Midwives

0 A celebration of 7 influential nurses NHS YEARS20 and midwives from 1948 to 18 In partnership with Seventy of the most influential nurses and midwives: 1948-2018 nursingstandard.com July 2018 / 3 0 7 years of nursing in the NHS Inspirational nurses and midwives who helped to shape the NHS Jane Cummings reflects on the lives of 70 remarkable As chief nursing officer for England, I am delighted figures whose contributions to nursing and to have contributed to this publication on behalf of midwifery are summarised in the following profiles, the CNOs in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and on the inspiration they provide as the profession identifying some of the most influential nurses and Jane Cummings meets today’s challenges midwives who have made a significant impact across chief nursing officer the UK and beyond. for England I would like to give special thanks to the RCNi As a nurse, when I visit front-line services and and Nursing Standard, who we have worked in meet with staff and colleagues across the country partnership with to produce this important reflection I regularly reflect on a powerful quote from the of our history over the past 70 years, and to its American author and management expert Ken sponsor Impelsys. Blanchard: ‘The key to successful leadership today is influence, not authority.’ Tireless work to shape a profession I am a firm believer that everyone in our Here you will find profiles of 70 extraordinary profession, whatever their role, wherever they work, nursing and midwifery leaders. Many of them have has the ability to influence and be influenced by the helped shape our NHS. -

Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations Through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’

Article Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’ Chamion Caballero Department of Theatre and Performance, Goldsmiths, University of London, London SE14 6NW, UK; [email protected] Received: 19 November 2018; Accepted: 6 April 2019; Published: 17 April 2019 Abstract: The popular conception of interraciality in Britain is one that frequently casts mixed racial relationships, people and families as being a modern phenomenon. Yet, as scholars are increasingly discussing, interraciality in Britain has much deeper and diverse roots, with racial mixing and mixedness now a substantively documented presence at least as far back as the Tudor era. While much of this history has been told through the perspectives of outsiders and frequently in the negative terms of the assumed ‘orthodoxy of the interracial experience’—marginality, conflict, rejection and confusion—first-hand accounts challenging these perceptions allow a contrasting picture to emerge. This article contributes to the foregrounding of this more complex history through focusing on accounts of interracial ‘ordinariness’—both presence and experiences— throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, a time when official concern about racial mixing featured prominently in public debate. In doing so, a more multidimensional picture of interracial family life than has frequently been assumed is depicted, one which challenges mainstream attitudes about conceptualisations of racial mixing both -

Character: Nurse Jenny Lee Age: 22 Role: Viewpoint Character Actors: Jessica Raine - Young Jenny Vanessa Redgrave - Mature Jennifer (VO)

Call the Midwife Carla Habeeb Recurring Characters – Bios and Backstory December 7, 2015 Character: Nurse Jenny Lee Age: 22 Role: Viewpoint Character Actors: Jessica Raine - Young Jenny Vanessa Redgrave - Mature Jennifer (VO) Jenny Lee was born in Clacton-on-Sea in 1935 and grew up in the Buckinghamshire town of Amersham. During Christmas 1934, Jenny’s parents – Elsie and Gordon – had a runaway affair, and when they returned home, it was soon discovered that Elsie was pregnant. To hide the disgrace of expecting a baby prior to marriage, they had a summer wedding and then took a trip to a seaside resort, Clacton-on-Sea, a few weeks before the due date. Gordon Lee later bought a holiday bungalow at Jaywick Sands, near Clacton and the family returned there for many happy vacations. And by living in Amersham, Jenny’s family was sheltered from the harshness of World War II, and her father’s business thrived and provided the opportunity to negotiate extra with food rationing. There were always great parties hosted by her parents at their house. When Jenny was 10, she was spending a seaside break at the bungalow with her mother and aunts, and her father stayed at home because of work. Jenny’s mother decided to return home early to surprise her husband since she was missing him, and she found him in bed with his secretary, Judith. Her mother collapsed and suffered a severe near fatal stroke, and was rushed to the hospital where she was there for several days for treatment. Jenny and her sister returned from vacation to an eerily silent home and all of the adults were acting strangely. -

About This Book

Page 1 of 3 Georgetown Township Public Library Book Discussion Guide Call the Midwife Jennifer Worth (2011) About This Book Jennifer Worth gained her midwife training in the 1950s among an Anglican order of nuns dedicated to ensuring safer childbirth for the poor living amid the Docklands slums on the East End of London. Her engaging memoir retraces those early years caring for the indigent and unfortunate during the pinched postwar era in London, when health care was nearly nonexistent, antibiotics brand-new, sanitary facilities rare, contraception unreliable and families with 13 or more children the norm. Working alongside the trained nurses and midwives of St. Raymund Nonnatus (a pseudonym she’s given the place), Worth made frequent visits to the tenements that housed the dock workers and their families, often in the dead of night on her bicycle. Her well-polished anecdotes are teeming with character detail of some of the more memorable nurses she worked with, such as the six- foot-two Camilla Fortescue-Cholmeley-Browne, called Chummy, who renounced her genteel upbringing to become a nurse, or the dotty old Sister Monica Joan, who fancied cakes immoderately. Patients included Molly, only 19 and already trapped in poverty and degradation with several children and an abusive husband; Mrs. Conchita Warren, who was delivering her 24th baby; or the birdlike vagrant, Mrs. Jenkins, whose children were taken away from her when she entered the workhouse. - Publishers Weekly From: http://www.penguin.com/book About the Author JENNIFER WORTH (1935-2011) trained as a nurse at the Royal Berkshire Hospital in Reading, England. -

A Neal Street Production for BBC One Created and Written by Heidi

A Neal Street Production for BBC One Created and written by Heidi Thomas and based on the best-selling memoirs of the late Jennifer Worth, Call the Midwife returns for a Christmas special in December 2012 and a second series early in 2013. Introduction by Heidi Thomas (Series Creator and Writer) I think the audience response to the first series of Call the Midwife was the warmest I’ve ever known. From the word go, it seemed it was loved not just by midwives and by mothers, but by one group we thought would turn off straight away – men! In fact I think my favourite fan of the show was a chap in his 70’s who came up to me in my local supermarket. With tears in his eyes, he told me how he had been banished from the room when his children were born, and Call the Midwife had at last allowed him to share in the miracle of birth. For everyone involved, the prospect of returning to the world of Nonnatus House was irresistible. Series 2 - like Series 1- draws heavily on the original, bestselling trilogy of books by Jennifer Worth and blends her stories with original material to create a multi-layered whole. However, having a Christmas special and eight episodes has given us the chance to delve more deeply into the lives of our regular characters. Each week, compelling tales of midwifery and social medicine intertwine with the touching, intimate stories of the nurses and nuns who serve the community of Poplar. Secrets are revealed, and lessons learned, as we follow these dedicated, vibrant women through the run-up to Christmas 1957, and then the spring, summer and autumn of 1958. -

2017 Newsletter

Cholesbury-cum-St Leonards Local History Group NEWSLETTER No. 21 2017 - 18 Chairman’s Introduction I hope you will enjoy this Newsletter which is packed with interesting articles. I am most grateful to this year’s contributors. The aims of our History Group have always been to stimulate interest in local history with interesting talks from knowledgeable and entertaining speakers, and to discover more about the history of the Hilltop Villages. Once again we have assembled a varied selection of talks, spanning historical topics, both local and national and sometimes both. A good example is the first presentation from family members of Jennifer Worth, best known for her book about her career on which the BBC drama Call The Midwife is based. However, Jennifer was born very near us in Amersham which gives it two ticks. There are talks about the Civil War, a hoard of gold, some local spies, Chenies Palace and John Lewis to enjoy. Do encourage along others who might enjoy them too. The History Group’s founding members started an archive of photos and documents, and gathered stories about villagers. Over the years our archive has grown impressively but we know more could be done to find out from the wealth of, so far, unexplored documents, people, places, events etc related to our villages. No matter what knowledge or experience you have of research or history if you would like to get involved do get in touch. I look forward to seeing you all again for our 54th season. Please let our Treasurer have your subscription and membership form either ahead of, or at, the October meeting. -

Farewell to the East End

Dedicated to Cynthia for a lifetime of friendship Farewell to the East End JENNIFER WORTH Table of Contents Cover Dedication Title Page Acknowledgements ‘YOUTH’S A STUFF WILL NOT ENDURE’ THREE MEN WENT INTO A RESTAURANT … TRUST A SAILOR CYNTHIA LOST BABIES SOOT NANCY MEGAN’MAVE MEG THE GYPSY MAVE THE MOTHER MADONNA OF THE PAVEMENT THE FIGHT THE MASTER’S ARMS TUBERCULOSIS THE MASTER THE MISTRESS THE ANGELS TOO MANY CHILDREN THE ABORTIONIST BACK-STREET ABORTIONS STRANGER THAN FICTION THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER ON THE SHELF THE WEDDING TAXI! ADIEU FAREWELL TO THE EAST END GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Author biography Also by Jennifer Worth Copyright ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks and gratitude to: Terri Coates, the midwife who inspired me to write these books, Dr Michael Boyes, Douglas May, Jenny Whitefield, Joan Hands, Helen Whitehorn, Philip and Suzannah, Ena Robinson, Mary Riches, Janet Salter, Maureen Dring, Peggy Sayer, Mike Birch, Sally Neville, the Marie Stopes Society. Special thanks to Patricia Schooling of Merton Books for first bringing my writing to an audience. All names have been changed. ‘The Sisters of St Raymund Nonnatus’ is a pseudonym. In 1855 Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter Vicky, the Crown Princess of Prussia, who was expecting a baby: What you say about the pride of giving life to an immortal soul is very fine, but I own I cannot enter into all that. I think very much more of our being like a cow or a dog at such moments, when our poor nature becomes so very animal and unecstatic. ‘YOUTH’S A STUFF WILL NOT ENDURE’ Someone once said that youth is wasted on the young.1 Not a bit of it. -

H-Life 05-02-13.Indd

Page 8 HHeralderald Thursday, May 2, 2013 ★ © 2013013 Vespoint Publishing, Publishing Inc. In ★ HEERALDRALD ARROUNDOUND TTHEHE WOORLDRLD Arizona Clinton Connie Trenta takes a hike at the Prescott National Forest in Arizona, experiencing Brother and sister Gary and Courtney Nicholas of Barberton, both Army staff sergeants, nature’s beauty at 6,000 feet above sea level. She visited fellow Barberton native Lisa visit the Ohio Veterans Memorial Park while home on leave. Feingold (Robinson) and also went fi shing. ‘Call the Midwife’ by Jennifer Worth ahamas A memoir of birth, joy and hard times he B Reviewed by: Mary Kay home deliveries T Ball were still very common in Jennifer Lee Worth the East End. trained as a nurse at the Jenny, her fellow Royal Berkshire Hospital midwives, and in Reading, England. She the Sisters later moved to London worked tirelessly to train as a midwife. Th e to provide safe fi rst book in her three part and quality care memoir, Worth’s “Call the to their patients Midwife,” recalls stories, and families. coworkers and patients The midwives she nursed while at the often travelled Nonnatus House. Jenny, to their patients’ as she was called in her fl ats in the dead memoir, worked with the of night on a Sisters of St. Raymund bike carrying Nonnatus ( a pseudonym their supplies for the Sisters of St. John the and instruments Divine) who ministered to with them. Matthew Toth and his parents, Brian and Dana, take a break after getting off the the working poor in Poplar The memoir Disney Dream cruise ship in Nassau, Bahamas during spring break. -

Making Connections 2011-2012

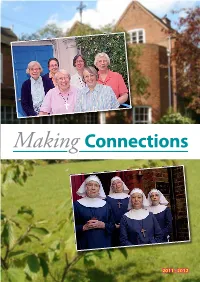

Making Connections 2011 - 2012 The Community of St. John The Divine The Mission Statement The Community of St. John the Divine, An Anglican Religious Community, live under the threefold Vows of Religious Life, establishing a centre of worship and prayer under the patronage of St. John the Divine, the Apostle of Love, and together with the Associates of the Community form a network of love, prayer and service. Within the ethos of healing,• wholeness and reconciliation, we exercise a ministry of hospitality for people to come for times of rest, retreat and renewal and to share in the life and worship of the Community. We seek to offer a ministry of spiritual accompaniment and pastoral care, and to respond to the needs of the poor and marginalised. The heart of our call• is to be a praying Community seeking God in our daily lives and serving Him in reaching out as channels of God’s love to others. Front cover photograph : Actresses as Sisters in “Call the Midwife” Copyright Neal Street Productions. Printed with• permission. Inset picture of the Real Sisters! Did you enjoy watching ‘Call the Midwife’? Did you wonder who inspired it? Well it was US, the Community of St. John the Divine This is how it really was Call The Midwife! Our Past Life and Work hits the TV Screen Monica and Marie Clare in the Clinic in the 1960’s he Community of St. John the presented with great sensitivity and national and local press, as well as Divine provided training for accurately portrayed the poverty in for features on television and radio. -

FEMINIST SAINTS Sermon by Rev

1 CALL THE MIDWIVES: FEMINIST SAINTS Sermon by Rev. Marti Keller Sunday, August 12, 2018 All Souls Church, New York City In the run-up to the (latest) Royal Wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle in May, PBS offered multiple Masterpiece episodes of Victoria, and her royal wedding, and The Crown was streamable on Netflix, reenacting Elizabeth II’s royal wedding. And there were assorted Diana bio pics and documentaries to put us in the mood for or to flesh out the back story of the internationally broadcast nuptials ahead. In the meantime, in another wing of the often beleaguered contemporary Windsor family, there was the other, rapidly being eclipsed Royal News, the very recent birth of a third child to Prince William and his Duchess, and the pull to stream another enormously popular British public television import, Call the Midwife, since it had been reported that Kate Middleton’s first two babies were delivered by, yes, she called in a midwife. Huge confession to a UU crowd: I am not a big PBS Masterpiece or any other British TV fan (John Lewis quote), but after having faithfully followed Downton Abbey, on the recommendation of my decidedly not a PBS devotee Gen X daughter, through its entire six seasons, I was searching around to fill that Sunday evening comfort television slot and ran across Call the Midwife. Same time, same station. This BBC series is based on a memoir by Jennifer Worth, who worked as a nurse midwife with the Community of St. John the Divine, an Anglican religious order founded in 1849. -

Volume 3 Issue 10 0 C I Autumn 2011

Aiscto;ii, NEWSLETTER Volume 3 Issue 10 Autumn 2011 0 C I OM MO -- _IMONM IMO NMI OM WIP alem1Wool IMO --."-r"._- WWI MO "" ..al don, •1•01 w•■• =MI(IBM solo - 4 ~ •=1/ 1M. MEM ■••• ..MI MM..=IP MIN IOW NM MI MIR .OW1 INN. =III •••• Oba.■1=0 p.m. •■■NM ow •••• MN MIS MI IMIGNIN NM OM AM Now mil•F MI Mg= um Nom 1... //Wm 1/40■112S2 NO=IN MN MI OMMN ■••••=1NO OM •=01.•14■ MO INIM Own ISM IMP ■•••■■ mo am.. OM aM. IMO MEI ....OM 0 ON =mom/ Nam Ma =. •M• iiir?.OM:elelffin.Ea ON— NION -■I, ■■• UM . =b■•■•■wm ••■■•••■•••••. anna MIN moll MN ...Kw/ .1•0 ••0 OM awl MN MO =M. IP ■■•••10 ••■• MID mono •■■•••••• mowma MIIINIMS .C77,4a (lenient Attlee statue restored and moved to Queen Mary, University of London, see John Rennie article CONTENTS: Cemetery Notes and News 2 Overshadowed by Churchill. hut rims 8 Attlee takes pride of place - John Rennie Programme Details 3 Correspondence 10 Obituaries - Res.Michael Peet and ♦ Book Revie‘%s 12 Jennifer Worth Cockney, and the Music Hall - Pat Francis S Mans Rents, Bromley St Leonard - 15 Robert Barber HMS Newsletter Autumn 21111 Editorial Note: Cemetery Notes and News The Committee members are as follows: Philip Merrick, Chairman. Doreen Kendall. fyou would like to join Doreen and Diane, Secretary. Harold Memick. Membership. and other volunteers of the East London David Behr. Programme, Ann Sansont. History Society in the Tower Hamlets Doreen Osborne. Howard Isenberg and Cemetery Park. on the second Sunday of every Rosemary Taylor. -

Mind, State and Society: Social History of Psychiatry and Mental Health In

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:47:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/113978B19265EDAD8CCA7567001475D1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:47:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/113978B19265EDAD8CCA7567001475D1 Mind, State and Society Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:47:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/113978B19265EDAD8CCA7567001475D1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:47:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/113978B19265EDAD8CCA7567001475D1 Mind, State and Society Social History of Psychiatry and Mental Health in Britain 1960–2010 Edited by George Ikkos Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital Nick Bouras King’s College London Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.234, on 25 Sep 2021 at 08:47:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/113978B19265EDAD8CCA7567001475D1 University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia 314–321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi – 110025, India 79 Anson Road, #06–04/06, Singapore 079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge.