Disintegration and Repetition: an Analysis Based on William Basinski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance and Installation by William Basinski and James Elaine

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ! ! MEDIA CONTACT Connie McAllister ALWAYS FRESH Director of Community Engagement ALWAYS FREE Tel 713 284 8255 [email protected] The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston presents a performance and installation by acclaimed composer William Basinski and artist James Elaine. Performance and installation by William Basinski and James Elaine At CAMH: Installation on view: Tuesday, October 8 – Sunday, October 13, 2013 Live Performance: Friday, October 11 | 7PM At Texas Contemporary Art Fair*: Special Installation: Thursday, October 10 – Sunday, October 13, 2013 *Location: George R. Brown Convention Center Houston, TX (August 19, 2013)—The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston is pleased to present a performance and installation by acclaimed composer William Basinski and artist James Elaine. An installation by the duo will be on view at CAMH as well as a site-specific installation for the Texas Contemporary Art Fair. A live performance by the two will take place at CAMH on Friday, October 11 at 7PM. Since 1978, James Elaine and William Basinski have worked together closely, creating some of the most visually poetic and aurally arresting installation and theatrical experiences. Using original compositions, found sound, tape loops, and delay devices, Basinski’s experimental music compositions provide a brilliant accompaniment to Elaine’s fragmented and painterly moving images recorded using super-8 video. By using obsolete technology and analogue tape loops, Basinki and Elaine explore the temporal nature of life, the reverberations of memory, and the mystery of time. The result of their collaboration provides a melancholic meditation on the passing of time and the decay that remains in its wake. -

DISINTEGRATION Loop 1.1

SVILOVA | WILLIAM BASINSKI DISINTEGRATION LOOP 1.1 WILLIAM BASINSKI JUNE 18–JULY 31, 2014 www.svilova.org 1 SVILOVA | WILLIAM BASINSKI SCALE BE THY KING: THE BLACK Mirror OF William Basinski By David Keenan 1. Scalle Bee Thie Kynge. There is a magical idea, rarely articulated, that imagination is the world-creating matrix of desire, in other words that imagination is what translates a sensation into a thought. Disintegration Loops, still the central, emblematic work of the artist and composer William Basinski, conflates the biological with the constructed, the historical with the personal, by a creative act of imagination that would attempt to mimic the function of memory via accidental processes of auto-forgetting while connecting it with historical trauma –the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers as a head wound – and romantic portraiture, through the back cover recreation of Henry Wallis’s 1856 painting, The Death Of Chatterton, with Basinski posed as the dead 18th Century English poet, who poisoned himself in 1770, aged 17. Thomas Chatterton’s reputation as a forger of mystical poetry is of note here. From the age of 12 onwards he produced a run of strange, visionary verse that he claimed was the work of a 15th century monk of his own invention, Thomas Rowley. Indeed, a particular adjective, “Rowliean”, has been coined to describe the works of this historical figment, this shade birthed of an intoxicated imagination. Rowley’s verse is difficult, its language being largely derived from Chatterton’s study of the English philologist John Kersey’s Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, “comprehending a brief explication of all sorts of difficult words”. -

Age of Displacement As the U.S

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | FEBRUARY | FEBRUARY CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Mayoral Spotlight on Bill Daley Nate Marshall 11 Aldermanic deep dives: DOOR TO DOOR IN THE 25TH Anya Davidson 12 THE SOCIALIST RAPPER IN THE 40TH Leor Galil 8 INSIDE THE 46TH Maya Dukmasova 6 Astra Taylor asks what democracy is Sujay Kumar 22 Age of displacement As the U.S. government grinds to a halt and restarts over demands for a wall, two exhibitions examine what global citizenship looks like. By SC16 THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | FEBRUARY | VOLUME NUMBER TR - A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR @ HAPPYVALENTINE’SDAY! To celebrate our love for you, we got you a LOT lot! FOUR. TEEN. LA—all of it—only has 15 seats on its entire city council. PTB of stories about aldermanic campaigns. Our election coverage has been Oh and it’s so anticlimactic: in a couple weeks we’ll dutifully head to the ECAEM so much fun that even our die-hard music sta ers want in on it. Along- polls to choose between them to determine who . we’ll vote for in the ME PSK side Maya Dukmasova’s look at the 46th Ward, we’re excited to present runo in April. But more on that next week. ME DKH D EKS Leor Galil’s look at the rapper-turned-socialist challenger to alderman Also in our last issue, there were a few misstatements of fact. Ben C LSK Pat O’Connor in the 40th—plus a three-page comics journalism feature Sachs’s review of Image Book misidentifi ed the referent of the title of D P JR CEAL from Anya Davidson on what’s going down in the 25th Ward that isn’t an part three. -

Drone Music, Fiction, and Composition As Apocalypse

MMus Creative Practice 201819 MU71075B: Creative Project DRONE MUSIC, FICTION, AND COMPOSITION AS APOCALYPSE Varun Kapoor Kishore A thesis submitted to the Department of Music at Goldsmiths, University of London in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music. September 10, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 CONTEXT A BRIEF HISTORY OF DRONE 3 FURTHER CONTEXT: PHILL NIBLOCK, ALTERNATIVE NOTATION, IMPROVISATION 5 DRONE & APOCALYPSE 7 COMMENTARY APOCALYPTIC PROCESS 9 TOOLS: SYSTEM 11 THOUGHT-FICTIONS AND DRONE MAPS: BESŹELCOMA 12 PHONETIC TEXT SCORES FOR DRONE MUSIC: DRONETICS 22 CONCLUSION 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY REFERENCE LIST 27 DISCOGRAPHY 30 APPENDICES TRACK LIST 31 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS 32 INTRODUCTION We are all philosophers here where I am, and we debate among many other things the question of where it is that we live . I live in the interstice yes, but I live in both the city and the city. (Miéville 2009, 312) Literature, particularly fiction, has always been a part of my creative process in some form or another. From my first sciencefantasy concept album to my work with spoken word poetry and theatre, music inspired by or based on various kinds of text has permeated my practice for many years—I have always relied on a narrative approach akin to film scoring. While this approach has its place, my goal here was to engage with text in ways that relied less on semantics and more on the properties of text. This led to experiments with Morse code, time signatures based on word lengths, various attempts at correlating letters to pitch—treating text as physical material rather than a “meaningful” sum of its parts. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Time and Technology in William Basinski's the Disintegration Loops

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 18:17 Intermédialités Histoire et théorie des arts, des lettres et des techniques Intermediality History and Theory of the Arts, Literature and Technologies (De)compositions: Time and Technology in William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops (2002) Jakko Kemper restituer (le temps) Résumé de l'article rendering (time) Cet article analyse l’album The Disintegration Loops (2002), de William Numéro 33, printemps 2019 Basinski, et soutient que son interprétation esthétique de la temporalité et de la finitude est pertinente au regard de la relation entre technologie et perception URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065020ar humaine du temps pour trois raisons. Premièrement, l'appareil technologique DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1065020ar responsable de sa création reflète les concepts derridéens d'espacement et d'auto-immunité. Deuxièmement, l’appel affectif de l’album illustre la notion de chronolibido de Martin Hägglund. Troisièmement, la musique donne lieu à Aller au sommaire du numéro une expérience médiatique temporelle qui contraste avec l'expérience médiatique offerte par ce que Mark B.N. Hansen appelle les « médias du 21e siècle ». Ensemble, ces trois dimensions font de The Disintegration Loops un Éditeur(s) objet qui permet de donner une base empirique aux théories discutées du temps et des médias. Revue intermédialités ISSN 1920-3136 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Kemper, J. (2019). (De)compositions: Time and Technology in William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops (2002). Intermédialités / Intermediality, (33). https://doi.org/10.7202/1065020ar Tous droits réservés © Revue Intermédialités, 2019 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

An Aesthetic of the Irreducible Ryan Patrick Maguire

An Aesthetic of the Irreducible Ryan Patrick Maguire Milwaukee, WI Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2015 Master of Arts, Dartmouth College, 2013 Undergraduate Diploma, New England Conservatory, 2010 Bachelor of Arts, Beloit College, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music University of Virginia May, 2019 Edward Coffey (chair) A.D. Carson Luke Dahl Mona Kasra Noel Lobley Contents Table of Contents ii List of Figures iii Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Inhalation vii Chapter 1: A Capella 1 moDernisT 2 Verse One 8 BRK 17 BCKSTRY 26 TCHNCS 35 Vision 38 Materiality 43 Meditation 51 Chapter 2: Accumulation 54 Ghost/Ambient 54 $†@® 58 freeLanguage 62 Harvest Light 65 white, pink, brown 66 Rest, 1-3 68 Ghost in the Codec 69 Pure Beauty 74 Resolution Disputes 75 Live/Improvisation 76 Photography, Clothing, Stickers, etc. 77 Sample Library 78 In Progress 79 Exhalation 82 Code 84 Audio Detritus 84 Image Detritus 89 Video Detritus 89 Interactive Detritus 91 Bibliography 103 ii List of Figures Figure 1. MPEG-4 detritus from the video “Tom’s Diner” xi Figure 2. Sections of the song “Tom’s Diner” 2 Figure 3. The opening breath in moDernisT as adaptive spectrogram 4 Figure 4. moDernisT in the digital audio workstation 4 Figure 5. 9 Figure 6. moDernisT as waveform 12 Figure 7. moDernisT spectral flux 15 Figure 8. Spectral flux during verse two 16 Figure 9. moDernisT zero-crossing rate 21 Figure 10. Inharmonicity in verses three and four 22 Figure 11. -

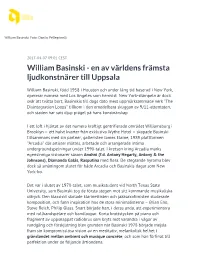

William Basinski

William Basinski. Foto: Danilo Pellegrinelli 2017-04-07 09:01 CEST William Basinski - en av världens främsta ljudkonstnärer till Uppsala William Basinski, född 1958 i Houston och under lång tid baserad i New York, opererar numera med Los Angeles som hemvist. New York-stämpeln är dock svår att tvätta bort; Basinskis till dags dato mest uppmärksammade verk ”The Disintegration Loops” tillkom i den omedelbara skuggan av 9/11-attentaten, och staden har satt djup prägel på hans konstnärskap. I ett loft i hjärtat av det numera kraftigt gentrifierade området Williamsburg i Brooklyn – ett halvt kvarter från exklusiva Wythe Hotel – skapade Basinski tillsammans med sin partner, galleristen James Elaine, 1989 plattformen ”Arcadia” där artister möttes, arbetade och arrangerade intima undergroundspelningar under 1990-talet. I kretsen kring Arcadia märks egensinniga visionärer såsom Anohni (f.d. Antony Hegarty, Antony & the Johnsons), Diamanda Galás, Rasputina med flera. De stegrande hyrorna blev dock så småningom slutet för både Arcadia och Basinskis dagar som New York-bo. Det var i slutet av 1970-talet, som musikstudent vid North Texas State University, som Basinski tog de första stegen mot sitt kommande musikaliska uttryck. Den klassiskt skolade klarinettisten och jazzsaxofonisten studerade komposition, och fann inspiration hos de stora minimalisterna – Brian Eno, Steve Reich, Philip Glass. Snart började han, i deras anda, att experimentera med rullbandspelare och bandloopar. Korta brottstycken på piano och fragment av uppsnappat radiobrus som bryts mot varandra i vågor av rundgång och förskjutning blev grunden när Basinski 1978 började mejsla fram sin kompromisslösa vision av en meditativ, melankolisk helhet i gränslandet mellan ambient och musique concrète, och som han förfinat till perfektion under de följande årtiondena. -

ALONZO-THESIS-2021.Pdf

Alone In The Ethereal Haze by Noah Alonzo, A.A., B.S. A Thesis In Composition Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Jennifer Jolley Chair of the Committee Hideki Isoda Dr. David Forrest Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 © 2021, Noah Alonzo Texas Tech University, Noah Alonzo, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This album would not be possible without the help and support of my professors, Dr. Jolley and Professor Isoda. Thank you to all my family and friends who have encouraged me while working on this project. ii Texas Tech University, Noah Alonzo, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... iv I. DETAILED STATEMENT .............................................................................. 1 Liner Notes to Alone in the Ethereal Haze ....................................................... 2 O .................................................................................................................. 3 dreams and ambitions crumble .................................................................... 3 eremophobia ................................................................................................ 3 rain in b ...................................................................................................... -

Every Sound You Can Imagine

Perspectives 163 Every Sound You Can Imagine Perspectives 163 Perspectives 163 This publication has been prepared in conjunction with Perspectives 163: Every Sound You Can Imagine, organized by guest curator Christoph Cox in association with Toby Kamps, senior curator, and Robert Shimshak, guest curator, for the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, October 3–December 7, 2008. Every Sound You Can Imagine The Perspectives Series is made possible by major grants from Fayez Sarofim; The Studio, the young professionals group of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston; and by donors to the Museum’s Perspectives Fund: Anonymous Fund at the Kerry Inman and Denby Auble Community Foundation of Abilene Solange Knowles Suzette and Darrell Betts Marley Lott COADE Engineering Software Mike and Leticia Loya Susie and Sanford Criner Belinda Phelps and Randy Howard Heidi and David Gerger William F. Stern Leslie and Mark Hull Vitol Inc. Perspectives catalogues are made possible by a grant from The Brown Foundation, Inc. The Museum’s operations and programs are made possible through the generosity of the Museum’s trustees, patrons, members, and donors. The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston receives partial operating support from the Houston Endowment, Inc., the City of Houston through the Houston Museum District Association, and the Texas Commission on the Arts. Official airlines of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston ISBN 978-1-933619-15-6 Design: Don Quaintance, Public Address Design © 2008 Contemporary Arts Museum Houston Design/Production Assistant: Elizabeth Frizzell All rights reserved. Printing: University of Texas Printing Services Contemporary Arts Museum Houston 5216 Montrose Blvd. Houston, Texas 77006-6598 tel. 713/284-8250 fax 713/284-8275 www.camh.org Reproductions © the artists, the composers, and the Back cover: John Cage, “Fontana Mix,” 1958. -

William Basinski, the Disintegration Loops. De L'érosion De L

WILLIAM BASINSKI PAR CHRISTOPHE LEVAUX The Disintegration Loops. – © Damon Lobel De l’érosion de l’espace sonore. L’antithèse totaliste. 24 I R&C 101 HISTOIRE DES DISINTEGRATION découvrant le schéma de mise en boucle de alors à s’extirper de la raideur structurelle LOOPS DE WILLIAM BASINSKI bandes magnétiques affi ché sur la pochette qui marquait ses premières œuvres (Reich, EST DÉSORMAIS IMPRIMÉE de Discreet Music (1975) du même Eno que p. 94). Philip Glass, dernier maillon de la SUR BIEN DES PAGES (VOIR L’ BASINSKI décide de se procurer le matériel chaîne minimaliste et le plus “mécaniste” de NOTAMMENT BOISSEL : 2009, P.149- nécessaire à l’élaboration des paysages sonores tous, ne prendra même plus la peine de passer 154). DURANT L’ÉTÉ 2001, LE COMPOSITEUR EXHUME UNE SÉRIE DE qui feront sa marque de fabrique. Il développe par la bande pour continuer à développer sa BOUCLES DE BANDES MAGNÉTIQUES alors sa musique pour bandes à New York dès musique pulsée et additive. le début des années 1980. Alternant travail QU’IL AVAIT LAISSÉES DEPUIS Au début des années 1970, l’étiquette de composition et collaborations éphémères QUELQUES ANNÉES DE CÔTÉ. AFIN DE “minimaliste” est collée sur les œuvres de LES PRÉSERVER DE LEUR DÉGRADATION avec la scène musicale underground de Young, Riley, Reich et Glass. L’entreprise GRADUELLE, IL LES TRANSFÈRE Williamsburg, il peine à faire publier et est alors menée par Michael Nyman, l’un SUR SUPPORT NUMÉRIQUE. AU FIL entendre sa musique. Le XXIe siècle se profi le des premiers compositeurs de la seconde DE L’OPÉRATION POURTANT, LES à l’horizon. -

The Kitchen Videos and Records, 1971-2011 (Bulk 1971-1999)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8jh3rrr Online items available Finding aid for The Kitchen videos and records, 1971-2011 (bulk 1971-1999) Judy Chou, Mark Simon Haydn, Emmabeth Nanol and Laura Schroffel. Finding aid for The Kitchen 2014.M.6 1 videos and records, 1971-2011 (bulk 1971-1999) Descriptive Summary Title: The Kitchen videos and records Date (inclusive): 1967-2011 (bulk 1971-1999) Number: 2014.M.6 Creator/Collector: Kitchen Center for Video, Music, Dance, Performance, Film, and Literature (New York, N.Y.) Physical Description: 426 Linear Feet(446 boxes, 7 flat file folders, 1 boxed roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The Kitchen has been a center for innovative artistic activity since its founding in 1971. Operating as a meeting place between disciplines in New York, the space has fostered the development of experimental artwork across music, video, dance, performance, and installation art. The archive predominantly contains extensive video and audio recordings documenting performances at the space; artist files; posters; and printed ephemera. Audio and video recordings are unavailable until reformatted. Contact the repository for information regarding access. Some audiovisual material is currently available for on-site use only. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The Kitchen was founded in 1971 as an artist collective by video artists Steina and Woody Vasulka.