The Development and Improvement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents: Grades

TEXAS Table of Contents GRADES 6–8 Create Your Story 6 7 8 TEXAS Student Edition TryPearsonTexas.com/LiteracyK-8 6 7 8 TEXAS Student Edition 6 7 8 TEXAS Student Edition is a trademark of MetaMetrics, Inc., and is registered in the United States and abroad. The trademarks and names of other companies and products mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners. TEXA S TEXA S t u d e n t E d i t i o n S LitSam581L694 TEXA S t u d e n t E d i t i o n S 6 7 8 S t u d e n t E d i t i o n PearsonRealize.com 6 7 8 6 7 8 TryPearsonTexas.com/LiteracyK-8 Join the Conversation: 800-527-2701 Twitter.com/PearsonPreK12 Facebook.com/PearsonPreK12 Copyright Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All rights reserved. SAM: 9781418290467 Get Fresh Ideas for Teaching: Blog.PearsonSchool.com ADV: 9781418290603 TEXAS Table of Contents The Importance of Literature myPerspectives Texas ensures that students read and understand a variety As individuals we are the sum of the stories that we tell ourselves about of complex texts across multiple genres such as poetry, realistic fiction, ourselves—about love, about fear, about life, about longing. We are adventure stories, historical fiction, mysteries, humor, myths, fantasy, drawn to those stories outside of classrooms because those stories tell us science fiction, and short stories. something about ourselves. They affirm something inside of us. They help These texts have been carefully selected to enable students to encounter us learn more about ourselves and others. -

A Message for Lent from Rev. David Madden

10 Creative Ways to Explore a Bible Passage by Jeremy Steele (www.umcom.org)(Note: This is a helpful and interesting article. Since space is limited, this will be a two or three part article, spread out in two or three newsletters.) #1 #14 Last month (February 2017 Methodist Dimension), we covered 1) Decode the Story and 2) Decipher the Argument, as ways to explore the Bible. Here are additional suggestions of out-of-the-box ways to explore, study and better communicate the Bible’s message. Good to the last drop 3. Design a comic strip: This method can be great when used with the first two ideas. Break the passage into eight or fewer discrete scenes and draw the key action of each scene paired with dialogue or important narration. This is all about exploring the passage by imagining what else is happening in the surroundings. What are the reactions of the other people? Do any props come into play? How are they held/used? How does the setting shape the scene? Don’t be afraid to use stick figures! 4. Create a meme: The current trend of placing a catchy word or phrase on top of an image is not only fun, but can also help you explore the Bible. Imagine that you are encouraging people to read a specific passage of the Bible. What phrase would hook Volume V – Issue 3 March 2017 people to read more? What image both matches the theme of the verse, and inspires curiosity? sample of a ‘meme’ 2017 5. Become a Bible translator: Don’t worry; we’re not arguing that you need to take several years of biblical languages to understand the Bible. -

Louisiana Tech Women’S Basketball

2013-14 LOUISIANA TECH WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2013-14 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL OPENING TIP GAME 9 LOUISIANA TECH NORTHWESTERN ST LADY TECHSTERS VS. DEMONS Date: Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2013 (2-6, 0-0 C-USA) (4-3, 0-0 Southland) Tipoff : 6 p.m. CT Location: Ruston, La. Head Coach: Teresa Weatherspoon Stat Leaders (per game) Head Coach: Brooke/Scott Stoehr Stat Leaders (per game) Arena: Thomas Assembly Center Record at LA Tech: 89-57 (5th) Points: Frazier 17.0 Record at School: 16-21 (2nd) Points: Armstead 19.1 Series: LA Tech leads 21-6 Career Record: Same Rebounds: Frazier 7.6 Career Record: Same Rebounds: Armstead 7.0 Assists: Walter 5.6 Assists: Perez 5.0 Television: None Blocks: Langston 0.6 Blocks: Armstead 1.1 Radio: LA Tech Sports Network Steals: Walter 3.5 Steals: Lee 1.6 ESPN 97.7 FM (Ruston) Talent: Malcolm Butler (pxp) PROBABLE STARTERS Louisiana Tech Ht. Yr. Hometown PPG RPG Other G 10 Chrisstasia Walter 5-7 Jr. Texarkana, Ark. 12.6 5.7 5.6 apg G 00 JaQuan Jackson 5-8 Fr. Killeen, Texas 14.3 3.4 1.5 apg 2013-14 SCHEDULE G 21 Kanedria Andrews 5-8 Jr. El Dorado, Ark. 4.1 4.4 1.5 apg F 2 Whitney Frazier 6-0 Jr. El Dorado, Ark. 17.0 7.6 1.6 spg Date Opponent [TV] Time/Result F 42 Veanca Hall 6-2 So. Monroe, La. 3.6 2.4 Nov. 10 at #22/21 South Carolina L, 68-45 Nov. 16 at Virginia L, 95-82 Setting the Stage Nov. -

Games Go Global 2012 Get Ready

2012 Games Go Global 2012 Get Ready Introduction .........................................................................................................................01 The History of the Olympic Games .....................................................................................02 The Paralympics ...................................................................................................................02 The Games Go Global badge ...............................................................................................03 Guidelines for Leaders .........................................................................................................04 Get Set Warm Up Activities ..............................................................................................................05 GO! Activities Part One – Stadium ..............................................................................................08 2012 Olympic Sports ...........................................................................................................11 Activities Part Two – Temple ...............................................................................................12 2012 Paralympic Sports.......................................................................................................16 Activities Part Three – Theatre ............................................................................................17 Forms of Culture in the Cultural Olympiad .........................................................................20 -

Sports Quotes

SPORTS QUOTES The following quote library is provided as a service by Josephson Institute and its Pursuing Victory With Honor sportsmanship initiative. For more information on our campaign and materials, go to www.JosephsonInstitute.org/sports. The moment of victory is much too short to live for that and nothing else. – Martina Navratilova, tennis player If it is a cliché to say athletics build character as well as muscle, then I subscribe to the cliché. – Gerald Ford, 38th President Sports gives your life structure, discipline, and a pure fulfillment that few other areas of endeavor provide. – Bob Cousy, basketball player One man practicing good sportsmanship is far better than 50 others preaching it. – Knute Rockne, football coach I never thought about losing, but now that it’s happened, the only thing is to do it right. – Muhammad Ali, boxer Football is like life. It teaches work, sacrifice, perseverance, competitive drive, selflessness, and respect for authority. – Vince Lombardi, football coach World War II was a must win. – Marv Levy, football coach Dictators lead through fear; good coaches do not. – John Wooden, basketball coach A good coach will make his players see what they can be rather than what they are. – Ara Parseghian, football coach I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career, lost almost 300 games, missed the game- winning shot 26 times. I’ve failed over and over again in my life. That is why I succeed. – Michael Jordan, basketball player Champions keep playing until they get it right. – Billie Jean King, tennis player You miss 100 percent of the shots you never take. -

WOMEN in SPORTS Live Broadcast Event Wednesday, October 14, 2020, 8 PM ET

Annual Salute to WOMEN IN SPORTS Live Broadcast Event Wednesday, October 14, 2020, 8 PM ET A FUNDRAISING BENEFIT FOR Women’s Sports Foundation Sports Women’s Contents Greetings from the Women’s Sports Foundation Leadership ...................................................................................................................... 2 Special Thanks to Yahoo Sports ....................................................................................................................................................................4 Our Partners ....................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Benefactors ......................................................................................................................................................................................................6 Our Founder .....................................................................................................................................................................................................8 Broadcast Host ................................................................................................................................................................................................9 Red Carpet Hosts ............................................................................................................................................................................................10 -

A-050-Series-II Louisiana Tech University, Office of Special

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons University Archives Finding Aids University Archives 2019 A-050-Series-II Louisiana Tech University, Office of Special Programs, Photographs and Films, 1909-2002, Series II University Archives and Special Collections, Prescott eM morial Library, Louisiana Tech University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/archives-finding-aids Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Louisiana Tech University, Office of Special Programs, Photographs and Films, A-050-Series-II, Box Number, Folder Number, Department of University Archives and Special Collections, Prescott eM morial Library, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, Louisiana This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Louisiana Tech Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Archives Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Louisiana Tech Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A-050-Series-II-1 A-050-Series-II LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY, OFFICE OF SPECIAL PROGRAMS, PHOTOGRAPHS AND FILMS, 1909-2002, SERIES II. SCOPE AND CONTENT Photographs and negatives of students, campus activities and scenes; arranged chronologically. 50 boxes. BOX FOLDER DESCRIPTION NEGATIVES 001 001 Old Copy Prints; one photo each Typewriting Department, 1900's Domestic Science Department, 1900's Beta Psi Sorority [Feb. 1908] Basketball team, 1909-1910 (Coach Prince) Senior Class, 1910 Volley Club, 1910 002 Homecoming Court, 1936 Queen: Nelda Nobles Attendants: Carolyn Cupp Doris Davenport Evelyn Wall Mary Lee Lord Ruple (Mrs. Bill) Mardi Gras Dance, 1938 (one photo included) Best All-Around Athlete, 1938-1939 (Publicity shots) 003 Unidentified People, 1939 Lagniappe copy, November 1939 Pep Rally, 1939 Football, 1939 Pep Rally, Northwestern State Fair Game,1958 004 Graduation, 1940 Lagniappe Copy, 1940 Old President's House, 1940-1958 Tech Symphony Orchestra, Jan. -

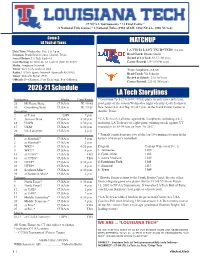

2020-21 Schedule MATCHUP LA Tech Storylines

2020-21 LOUISIANA TECH WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 27 NCAA Tournaments * 13 Final Fours * 8 National Title Games * 3 National Titles (1981 AIAW, 1982 NCAA, 1988 NCAA) Gamel 3 LA Tech at Texas MATCHUP LA TECH LADY TECHSTERS (2-0, 0-0) Date/Time: Wednesday, Dec. 2 at 7 p.m. Location: Frank Erwin Center (Austin, Texas) Head Coach: Brooke Stoehr Series History: LA Tech leads 8-3 Record at LA Tech: 68-57 (5th year) Last Meeting: #2 Texas 88, LA Tech 54 (Nov. 30, 2017) Career Record: 139-115 (9th year) Media: Longhorn Network Talent: Alex Loeb, Andrea Lloyd Texas Longhorns (2-0, 0-0) Radio: LA Tech Sports Network (Sportsalk 99.3 FM) Head Coach: Vic Schaefer Talent: Malcolm Butler (PxP) Record at School: 2-0 (1st Year) Officials: Dee Kantner, Scott Yarbrough, Roy Gulbeyan Career Record: 223-62 (9th year) 2020-21 Schedule LA Tech Storylines November Media Time/Result * Louisiana Tech (2-0, 0-0 C-USA) plays its only non-conference 25 McNeese State CUSA.tv W, 90-45 road game of the season Wednesday night when the Lady Techsters 30 Grambling State CUSA.tv W, 79-69 face Texas (2-0, 0-0 Big 12) at 7 p.m. at the Frank Erwin Center in December Austin, Texas. 2 at Texas LHN 7 p.m. 8 Jackson State CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. * LA Tech is 8-3 all-time against the Longhorns, including a 4-1 14 UAPB CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. in Austin. LA Tech saw its eight-game winning streak against UT 17 ULM CUSA.tv 6:30 p.m. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

Bayard Rustin by Monineath 28

ACHIEVING EQUALITY Student Profles of American Changemakers By the Students of Lowell High School’s Seminar on American Diversity Edited by Jessica Lander Lowell, Massachusetts Foreword Whose history do we study? Whose stories do we remember? Whose lives do we celebrate? These are some of the questions my students asked as we set out to research, edit, and write Achieving Equality. This year, I have had the privilege of guiding these students in a seminar that explores the history of diversity in America. My students are deeply qualifed to tackle this challenging and meaningful work. They attend Lowell High School in the historic mill city of Lowell, Massachusetts. The city is rich with the stories of immigrants who brought with them hopes and dreams for a more just future. From the Puritans in the mid-1600s, to the Polish in the early 1800s, to the Cambodians in the late 1900s, and to the Syrians who are arriving now, communities from around the world have always found a home in Lowell. More than one hundred years before the Little Rock Nine integrated Central High in 1957, Lowell High became the very frst integrated high school in the United States: open to all from its founding in the 1830s. Today, our school is one of the most diverse in the nation, home to students from more than 60 countries across fve continents. In our class, we have debated the long and often messy history of America’s fght for equality, justice, and recognition – a path that is rarely linear. Our understanding has been made richer by the diverse personal identities and histories of the students in our class. -

1999-00 NCAA Women's Basketball Championships Records

Bsktball_W (99-00) 11/28/00 12:03 PM Page 368 36 8 DIVISION I Ba s k e t b a l l DIVISION I 2000 Championship Hi g h l i g h t s Huskie Hustle: Pressure defense and quick hands helped Connecticut steal an early, insur- mountable lead over Tennessee and claim the Division I Women’s Basketball Championship April 2 in Philadelphia, 71-52. The Huskies built a 15-point lead a little more than 12 minutes into the first half, and Tennessee could never recover. The Lady Vols, who had been averaging 80 points per game, took 13 min- utes to reach 10 points in the national title game. The Huskies were led by the Final Four’s most outstanding player, Shea Ralph, who set the tone for her team defensively with six steals and added 15 points and seven assists to the victory. Connecticut earned its second national title five years to the day after its first championship win in 1995. The Huskies finished the season with a 36-1 record and avenged their only loss of the sea- son at the hands of the Lady Vols, February 2, 72-71. All-Tournament Team: Ralph was joined on the all-tournament team by teammates Sue Bird, Svetlana Abrosimova and Asjha Jones. Tennessee’s Tamika Catchings was also honored. TOURNAMENT SCORING LEADERS Player, Team G FG FG A Pc t . FT FT A Pc t . Rb . Av g . As t . Pt s . Av g . LaNeisha Caufield, Oklahoma.. 3 26 43 .6 0 5 18 22 .8 1 8 18 6. -

SCR156 Enrolled

Regular Session, 2014 ENROLLED SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 156 BY SENATORS LONG AND GALLOT AND REPRESENTATIVES BROWN AND COX A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commend Venus Lacy on being named to the 2014 Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame Induction Class. WHEREAS, each year Louisiana's sports writers select a limited number of athletes, past or present, who have become figures of national and international renown to be regarded as the state's immortals in the spheres of athletes and enshrined in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame; and WHEREAS, the 2014 Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame Class includes former Louisiana Tech basketball start Venus Lacy; and WHEREAS, after a successful start to her career at Brainerd High School, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where she was named Miss Basketball, she played for Old Dominion University; and WHEREAS, after her freshman year, she transferred to Louisiana Tech University, where she was a starting center for the Lady Techsters from 1988 to 1990 and was part of the national championship team that won the NCAA title in 1988; and WHEREAS, during her successful career as a Lady Techster, she was twice named Player of the Year for both the American South Conference and for the state of Louisiana; and WHEREAS, she maintains the top scoring average in Tech basketball history and is in the top five for career points, field goals made, field goals attempted, and blocked shots; and WHEREAS, before her retirement from basketball in 1998, Ms. Lacy played on the 1996 U.S. Olympic team that won a gold medal, played in the American Basketball League, and spent two seasons with the New York Liberty of the Women's National Basketball Association; and Page 1 of 2 SCR NO.