By Trent A. Fisher and Werner Lemberg ([email protected]) This Manual Documents GNU Troff Version 1.20.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GNU Emacs Manual

GNU Emacs Manual GNU Emacs Manual Sixteenth Edition, Updated for Emacs Version 22.1. Richard Stallman This is the Sixteenth edition of the GNU Emacs Manual, updated for Emacs version 22.1. Copyright c 1985, 1986, 1987, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with the Invariant Sections being \The GNU Manifesto," \Distribution" and \GNU GENERAL PUBLIC LICENSE," with the Front-Cover texts being \A GNU Manual," and with the Back-Cover Texts as in (a) below. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License." (a) The FSF's Back-Cover Text is: \You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software. Copies published by the Free Software Foundation raise funds for GNU development." Published by the Free Software Foundation 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor Boston, MA 02110-1301 USA ISBN 1-882114-86-8 Cover art by Etienne Suvasa. i Short Contents Preface ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 Distribution ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 1 The Organization of the Screen :::::::::::::::::::::::::: 6 2 Characters, Keys and Commands ::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 3 Entering and Exiting Emacs ::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 15 4 Basic Editing -

Downloads." the Open Information Security Foundation

Performance Testing Suricata The Effect of Configuration Variables On Offline Suricata Performance A Project Completed for CS 6266 Under Jonathon T. Giffin, Assistant Professor, Georgia Institute of Technology by Winston H Messer Project Advisor: Matt Jonkman, President, Open Information Security Foundation December 2011 Messer ii Abstract The Suricata IDS/IPS engine, a viable alternative to Snort, has a multitude of potential configurations. A simplified automated testing system was devised for the purpose of performance testing Suricata in an offline environment. Of the available configuration variables, seventeen were analyzed independently by testing in fifty-six configurations. Of these, three variables were found to have a statistically significant effect on performance: Detect Engine Profile, Multi Pattern Algorithm, and CPU affinity. Acknowledgements In writing the final report on this endeavor, I would like to start by thanking four people who made this project possible: Matt Jonkman, President, Open Information Security Foundation: For allowing me the opportunity to carry out this project under his supervision. Victor Julien, Lead Programmer, Open Information Security Foundation and Anne-Fleur Koolstra, Documentation Specialist, Open Information Security Foundation: For their willingness to share their wisdom and experience of Suricata via email for the past four months. John M. Weathersby, Jr., Executive Director, Open Source Software Institute: For allowing me the use of Institute equipment for the creation of a suitable testing -

Linux from Scratch Version 6.2

Linux From Scratch Version 6.2 Gerard Beekmans Linux From Scratch: Version 6.2 by Gerard Beekmans Copyright © 1999–2006 Gerard Beekmans Copyright (c) 1999–2006, Gerard Beekmans All rights reserved. Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions are met: • Redistributions in any form must retain the above copyright notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer • Neither the name of “Linux From Scratch” nor the names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products derived from this material without specific prior written permission • Any material derived from Linux From Scratch must contain a reference to the “Linux From Scratch” project THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIBUTORS “AS IS” AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE REGENTS OR CONTRIBUTORS BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE. Linux From Scratch - Version 6.2 Table of Contents Preface -

Curriculum Vitae

Vancouver, BC Canada +1.604.551.7988 KipWarner [email protected] Senior Software Engineer / Co-chairman OPMLWG 07 August 2021 *** WARNING: MANGLED TEXT COPY. DOWNLOAD PDF: www.thevertigo.com/getcv.php?fix Education 2007 Artificial Intelligence, BSc (Cognitive Systems: Computational Intelligence & Design) Department of Computer Science, University of British Columbia 2005 Associate of General Science Kwantlen Polytechnic University Professional Experience Jul 2015 - Cartesian Theatre, Vancouver, British Columbia Present Senior Software Engineer Techniques: Artificial intelligence, asymmetric cryptography, build automation, continuous integration testing, digital signal processing, machine learning, MapReduce, REST architecture, SIMD, and UNIX server daemon. Technologies: AltiVec / POWER Vector Media Extension; Apport; Assembly; AVX, Autopkgtest; Avahi / Apple’s Bonjour; Bash; C++17; CppUnit; cwrap (nss_wrapper); DBus; debhelper; GCC; GDB; Git; GNU Autotools; GNU/Linux; init.d; libav / FFmpeg; lsbinit; M4; OpenBMC; OpenSSL; Pistache; pkg-config; PortAudio; PostgreSQL; PPA; Python; QEMU; quilt; sbuild / pbuilder; setuptools; SQLite; STL; strace; systemd; Swagger; Umbrello; and Valgrind. Standards: Debian Configuration Management Specification; Debian Database Application Policy; Debian Policy Manual; Debian Python Policy; DEP-8; Filesystem Hierarchy Standard; freedesktop.org; GNU Coding Standards; IEEE 754; JSON; LSB; OpenAPI Specification; POSIX; RFC 4180; RSA; SQL; UNIX System V; UML; UPnP; and Zeroconf. Hardware: Ported to 64-bit PC -

This Book Doesn't Tell You How to Write Faster Code, Or How to Write Code with Fewer Memory Leaks, Or Even How to Debug Code at All

Practical Development Environments By Matthew B. Doar ............................................... Publisher: O'Reilly Pub Date: September 2005 ISBN: 0-596-00796-5 Pages: 328 Table of Contents | Index This book doesn't tell you how to write faster code, or how to write code with fewer memory leaks, or even how to debug code at all. What it does tell you is how to build your product in better ways, how to keep track of the code that you write, and how to track the bugs in your code. Plus some more things you'll wish you had known before starting a project. Practical Development Environments is a guide, a collection of advice about real development environments for small to medium-sized projects and groups. Each of the chapters considers a different kind of tool - tools for tracking versions of files, build tools, testing tools, bug-tracking tools, tools for creating documentation, and tools for creating packaged releases. Each chapter discusses what you should look for in that kind of tool and what to avoid, and also describes some good ideas, bad ideas, and annoying experiences for each area. Specific instances of each type of tool are described in enough detail so that you can decide which ones you want to investigate further. Developers want to write code, not maintain makefiles. Writers want to write content instead of manage templates. IT provides machines, but doesn't have time to maintain all the different tools. Managers want the product to move smoothly from development to release, and are interested in tools to help this happen more often. -

Latexsample-Thesis

INTEGRAL ESTIMATION IN QUANTUM PHYSICS by Jane Doe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mathematics The University of Utah May 2016 Copyright c Jane Doe 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Jane Doe has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Cornelius L´anczos , Chair(s) 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Hans Bethe , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Niels Bohr , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Max Born , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Paul A. M. Dirac , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved by Petrus Marcus Aurelius Featherstone-Hough , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Mathematics and by Alice B. Toklas , Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. -

The Linux Command Line

The Linux Command Line Second Internet Edition William E. Shotts, Jr. A LinuxCommand.org Book Copyright ©2008-2013, William E. Shotts, Jr. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit the link above or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Fran- cisco, California, 94105, USA. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. This book is part of the LinuxCommand.org project, a site for Linux education and advo- cacy devoted to helping users of legacy operating systems migrate into the future. You may contact the LinuxCommand.org project at http://linuxcommand.org. This book is also available in printed form, published by No Starch Press and may be purchased wherever fine books are sold. No Starch Press also offers this book in elec- tronic formats for most popular e-readers: http://nostarch.com/tlcl.htm Release History Version Date Description 13.07 July 6, 2013 Second Internet Edition. 09.12 December 14, 2009 First Internet Edition. 09.11 November 19, 2009 Fourth draft with almost all reviewer feedback incorporated and edited through chapter 37. 09.10 October 3, 2009 Third draft with revised table formatting, partial application of reviewers feedback and edited through chapter 18. 09.08 August 12, 2009 Second draft incorporating the first editing pass. 09.07 July 18, 2009 Completed first draft. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................xvi -

Pipenightdreams Osgcal-Doc Mumudvb Mpg123-Alsa Tbb

pipenightdreams osgcal-doc mumudvb mpg123-alsa tbb-examples libgammu4-dbg gcc-4.1-doc snort-rules-default davical cutmp3 libevolution5.0-cil aspell-am python-gobject-doc openoffice.org-l10n-mn libc6-xen xserver-xorg trophy-data t38modem pioneers-console libnb-platform10-java libgtkglext1-ruby libboost-wave1.39-dev drgenius bfbtester libchromexvmcpro1 isdnutils-xtools ubuntuone-client openoffice.org2-math openoffice.org-l10n-lt lsb-cxx-ia32 kdeartwork-emoticons-kde4 wmpuzzle trafshow python-plplot lx-gdb link-monitor-applet libscm-dev liblog-agent-logger-perl libccrtp-doc libclass-throwable-perl kde-i18n-csb jack-jconv hamradio-menus coinor-libvol-doc msx-emulator bitbake nabi language-pack-gnome-zh libpaperg popularity-contest xracer-tools xfont-nexus opendrim-lmp-baseserver libvorbisfile-ruby liblinebreak-doc libgfcui-2.0-0c2a-dbg libblacs-mpi-dev dict-freedict-spa-eng blender-ogrexml aspell-da x11-apps openoffice.org-l10n-lv openoffice.org-l10n-nl pnmtopng libodbcinstq1 libhsqldb-java-doc libmono-addins-gui0.2-cil sg3-utils linux-backports-modules-alsa-2.6.31-19-generic yorick-yeti-gsl python-pymssql plasma-widget-cpuload mcpp gpsim-lcd cl-csv libhtml-clean-perl asterisk-dbg apt-dater-dbg libgnome-mag1-dev language-pack-gnome-yo python-crypto svn-autoreleasedeb sugar-terminal-activity mii-diag maria-doc libplexus-component-api-java-doc libhugs-hgl-bundled libchipcard-libgwenhywfar47-plugins libghc6-random-dev freefem3d ezmlm cakephp-scripts aspell-ar ara-byte not+sparc openoffice.org-l10n-nn linux-backports-modules-karmic-generic-pae -

Integral Estimation in Quantum Physics

INTEGRAL ESTIMATION IN QUANTUM PHYSICS by Jane Doe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematical Physics Department of Mathematics The University of Utah May 2016 Copyright c Jane Doe 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Jane Doe has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Cornelius L´anczos , Chair(s) 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Hans Bethe , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Niels Bohr , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Max Born , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved Paul A. M. Dirac , Member 17 Feb 2016 Date Approved by Petrus Marcus Aurelius Featherstone-Hough , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Mathematics and by Alice B. Toklas , Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah blah. -

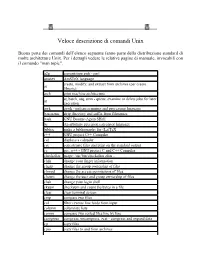

Unix Command

Veloce descrizione di comandi Unix Buona parte dei comandi dell’elenco seguente fanno parte della distribuzione standard di molte architetture Unix. Per i dettagli vedere le relative pagine di manuale, invocabili con il comando "man topic". a2p convertitore awk - perl amstex AmSTeX language create, modify, and extract from archives (per creare ar librerie) arch print machine architecture at, batch, atq, atrm - queue, examine or delete jobs for later at execution awk gawk - pattern scanning and processing language basename strip directory and suffix from filenames bash GNU Bourne-Again SHell bc An arbitrary precision calculator language bibtex make a bibliography for (La)TeX c++ GNU project C++ Compiler cal displays a calendar cat concatenate files and print on the standard output cc gcc, g++ - GNU project C and C++ Compiler checkalias usage: /usr/bin/checkalias alias .. chfn change your finger information chgrp change the group ownership of files chmod change the access permissions of files chown change the user and group ownership of files chsh change your login shell cksum checksum and count the bytes in a file clear clear terminal screen cmp compare two files col filter reverse line feeds from input column columnate lists comm compare two sorted files line by line compress compress, uncompress, zcat - compress and expand data cp copy files cpio copy files to and from archives tcsh - C shell with file name completion and command line csh editing csplit split a file into sections determined by context lines cut remove sections from each -

Var/Www/Apps/Conversion/Tmp

: gettext lvresize run_init ! gettextize lvs runlevel ./ gettext.sh lvscan running-circles [ gfortran lwp-download run-parts [[ ghostscript lwp-dump runuser ]] gif2tiff lwp-mirror rvi { gij lwp-request rview } gindxbib lwp-rget rvim a2p git lz s2p ab git-receive-pack lzcat sa abrt-backtrace git-shell lzcmp sadf abrt-cli git-upload-archive lzdiff safe_finger abrtd git-upload-pack lzegrep sandbox abrt-debuginfo-install gjar lzfgrep saned abrt-handle-upload gjarsigner lzgrep sane-find-scanner ac gkeytool lzless sar accept glibc_post_upgrade.x86_64 lzma saslauthd accton glookbib lzmadec sasldblistusers2 aclocal gls-dns-forward lzmainfo saslpasswd2 aclocal-1.11 gls-email-iptables lzmore saytime aconnect gls-grade-securevnc-backend lzop scanimage acpid gls-makebridge m4 scp acpi_listen gls-munge-grub magnifier script activation-client gls-munge-rootpw mail scriptreplay addftinfo gls-resetvm Mail scrollkeeper-config addgnupghome gls-vserver-network mailq scrollkeeper-extract addpart gls-vserver-network2 mailq.postfix scrollkeeper-gen-seriesid addr2line glxgears mailq.sendmail scrollkeeper-get-cl adduser glxinfo mailstat scrollkeeper-get-content-list agetty gmake mailstats scrollkeeper-get-extended-content-list alias gneqn mailx scrollkeeper-get-index-from-docpath alsactl gnome-about make scrollkeeper-get-toc-from-docpath alsa-info gnome-about-me MAKEDEV scrollkeeper-get-toc-from-id alsa-info.sh gnome-appearance-properties makedumpfile scrollkeeper-install alsamixer gnome-at-mobility makemap scrollkeeper-preinstall alsaunmute gnome-at-properties -

OSS Alphabetical List and Software Identification

Annex: OSS Alphabetical list and Software identification Software Short description Page A2ps a2ps formats files for printing on a PostScript printer. 149 AbiWord Open source word processor. 122 AIDE Advanced Intrusion Detection Environment. Free replacement for Tripwire(tm). It does the same 53 things are Tripwire(tm) and more. Alliance Complete set of CAD tools for the specification, design and validation of digital VLSI circuits. 114 Amanda Backup utility. 134 Apache Free HTTP (Web) server which is used by over 50% of all web servers worldwide. 106 Balsa Balsa is the official GNOME mail client. 96 Bash The Bourne Again Shell. It's compatible with the Unix `sh' and offers many extensions found in 147 `csh' and `ksh'. Bayonne Multi-line voice telephony server. 58 Bind BIND "Berkeley Internet Name Daemon", and is the Internet de-facto standard program for 95 turning host names into IP addresses. Bison General-purpose parser generator. 77 BSD operating FreeBSD is an advanced BSD UNIX operating system. 144 systems C Library The GNU C library is used as the C library in the GNU system and most newer systems with the 68 Linux kernel. CAPA Computer Aided Personal Approach. Network system for learning, teaching, assessment and 131 administration. CVS A version control system keeps a history of the changes made to a set of files. 78 DDD DDD is a graphical front-end for GDB and other command-line debuggers. 79 Diald Diald is an intelligent link management tool originally named for its ability to control dial-on- 50 demand network connections. Dosemu DOSEMU stands for DOS Emulation, and is a linux application that enables the Linux OS to run 138 many DOS programs - including some Electric Sophisticated electrical CAD system that can handle many forms of circuit design.