Kingdom of Tonga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budget Statement 2012-2013.Pdf

Budget Statement 2012‐2013 Government of the Kingdom of Tonga “CREATING OPPORTUNITY IN EXTRAORDINARY TIMES” ‘Ikale Tahi players rejoicing after victory over France at the 2011 Rugby World Cup, 1st October 2011, Wellington Regional Stadium Ministry of Finance & National Planning, Nuku’alofa, June 2012. Government of Tonga Budget Statement for year ending 30th June 2013 Table of Contents FIGURES .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 TABLES .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1 FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 2 THE NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT VISION ........................................................................................................... 7 2.1 OUTCOME OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 ENABLING THEMES ..................................................................................................................................... 7 3 BUDGET ESTIMATE AT A GLANCE .................................................................................................................... 8 4 MAIN BUDGET EXPENDITURE CHANGES ...................................................................................................... -

Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Mangrove and Coastal Ecosystems and Community Livelihoods in • Solomon Islands •

Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Mangrove and Coastal Ecosystems and Community Livelihoods in Solomon Islands Vanuatu Fiji Tonga Samoa September 2013 List of Abbreviations AOGCM Atmospheric-ocean general circulation model AR4 (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report (2007) BMU German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety BOM Bureau of Meteorology (Australia) CGPS Continuous Global Positioning System COSPPac Climate and Oceans Support Program in the Pacific GCM Global climate model ICCAI International Climate Change Adaptation Initiative IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IUCN ORO International Union for Conservation of Nature Oceania Regional Office MESCAL Mangrove Ecosystems for Climate Change Adaptation and Livelihoods PCCSP Pacific Climate Change Science Program PMI Pacific Mangroves Initiative PSLM Pacific Sea Level Monitoring (formerly known as SPSLCMP) SEAFRAME Sea Level Fine Resolution Acoustic Measuring Equipment SimCLIM SimCLIM Open Framework Modelling System SOPAC-SPC Applied Geoscience and Technology Division of the Secretariat of the Pacific Coummunity SPREP Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme SPSLCMP South Pacific Sea Level and Climate Monitoring Project (now known as PSLM) UNCBD United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change i Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... -

Integrated Strategic Planning, Medium-Term Fiscal Framework and Budgeting (Financed by the Technical Assistance Special Fund)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 38159 May 2006 Tonga: Integrated Strategic Planning, Medium-Term Fiscal Framework and Budgeting (Financed by the Technical Assistance Special Fund) Prepared by VINSTAR Consulting, Broad Horizons Limited, KVAConsult Limited For the Government of Tonga and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. TA No.4510 Tonga Integrated Strategic Planning, Medium-Term Fiscal Framework and Budgeting Final Report Presented to the Asian Development Bank and the Government of Tonga 5 May 2006 KINGDOM OF TONGA STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN EIGHT, 2006/07—2008/09: LOOKING TO THE FUTURE, BUILDING ON THE PAST SDP8 Third Draft May 2006 Table of Contents Page No. Map of Tonga vi Basic Information on Tonga vii Abbreviations viii Note x Foreword xi 1 Development Performance and Reforms 1 1.1 Overview of Economic and Social Development 1 1.2 Economic and Public Sector Reforms in 2000―2005 3 1.2.1 SDP7 4 1.2.2 EPSRP 5 1.2.3 Environmental Conservation 11 1.2.4 Summary 12 1.3 Economic Performance, FY2000―FY2006 12 1.4 Key Observations for Planners 19 2 The People’s Perspective on Development 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Community Consultations 21 2.2.1 Tongatapu 21 2.2.2 Vava’u 24 2.2.3 Ha’apai 26 2.2.4 ‘Eua 28 2.2.5 Niuafo’ou 29 2.2.6 -

Annual Report

CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Foreword ......................................................................................................................................... 4 3 OFFICE OF THE HON MINISTER. ...................................................................................................... 6 4 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER ................................................................................... 6 5 CORPORATE SERVICES DIVISION ..................................................................................................... 7 5.1 Workforce ............................................................................................................................... 7 5.1.1 Organisational Structure ................................................................................................. 8 5.2 Human Resource Development and Training ......................................................................... 8 5.2.1 Staff Appointments / Promotions/Resigned/Dismissed/Death ...................................... 8 5.2.2 Long-Term Study ............................................................................................................. 9 5.2.3 Short-Term Training, Workshops, Local and Overseas Meetings ................................... 9 5.3 Financial Section .................................................................................................................. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Introduction of Clean Energy by Solar Home System In

Ministry of Land Survey and Natural Resources Kingdom of Tonga PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR INTRODUCTION OF CLEAN ENERGY BY SOLAR HOME SYSTEM IN THE KINGDOM OF TONGA MARCH 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. ICONS INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION INC. SHIKOKU ELECTRIC POWER CO., INC. IDD CR(1) 10-035 Ministry of Land Survey and Natural Resources Kingdom of Tonga PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR INTRODUCTION OF CLEAN ENERGY BY SOLAR HOME SYSTEM IN THE KINGDOM OF TONGA MARCH 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. ICONS INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION INC. SHIKOKU ELECTRIC POWER CO., INC. PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) conducted the preparatory survey on the Project for Introduction of Clean Energy by Solar Home System in the Kingdom of Tonga. JICA sent to Tonga a survey team from 24th August to 19th September, 2009. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of Tonga, and conducted a field study at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. Then, a mission was sent to Tonga in order to discuss a draft outline design, and as this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Kingdom of Tonga for their close cooperation extended to the teams. March 2010 Kazuhiro YONEDA Director General Industrial Development Department Japan International Cooperation Agency March 2010 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL We are pleased to submit to you the preparatory survey report on the Project for Introduction of Clean Energy by Solar Home System in the Kingdom of Tonga. -

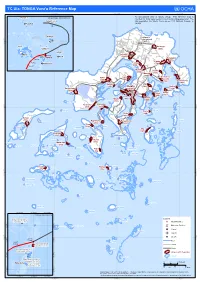

TC Ula: TONGA Vava'u Reference Map

TC Ula: TONGA Vava'u Reference Map 174°5'0"W 174°0'0"W 173°55'0"W TC Ula passed close to Vava'u Group. This reference map is TUVALU REGIONAL REFERENCE intended for initial reponse planning showing village population. The TOKELAU total population for Vava'u Group as per 2011 National Census is Funafuti 14,922. COOK ISLANDS Matu'anua WALLIS SAMOA AND FUTUNA Lupepau'u S S " Intermational " 0 0 ' ' 5 AMERICAN Airport 5 3 Apia 3 ° ° 8 SAMOA 8 1 1 FIJI Holonga TONGA (453) NIUE Leimatu'a Suva 01/18Z Vava'u 02/06Z Alofi (1105) Vava'u Ha'alaufuli 02/18Z (412) Ta'anea 03/06Z Nuku'alofa Feletoa (706) (388) 03/18Z Pousini 04/18Z Mataika Ha'akio (490) NEW Mangia (139) CALEDONIA (104) Houma mo Tefisi Taoa Faleono (588) (496) (136) Tu'anekivale (487) Vaimalo 'Utui (95) (302) Holeva Neiafu Tulie Longomapu (4051) (116) (613) Okoa Koloa (266) (197) Halaevalu Makave 'Utulei Wharf (443) Tu'ungasika Lotuma (132) S S " Tu'anuku 'Utungake " 0 0 ' ' 0 (311) Faioa 0 4 (313) 4 ° ° 8 8 1 'Olo'ua 1 Luafatu 'Olo'ua Toula (140) Tuita Pangaimotu Hunga (411) Hunga (119) Luamoko Kitu Nga'unoho Pangaimotu Mafana 'Umuna (218) (661) 'Otea (125) Mala Kalau Luakapa Nuapapu Ofu (161) Kenutu Nuapapu Ofu Fofoa (135) 'Oto A'a Kapa Afo Alinonga Falevai (113) Foelifuka Matamaka (147) Tapana Fafine Foeata Vaka'eitu Lape Nuku Kulo Lua'ofa Kapa Tu'anukulau (69) Langito'o Lautala Fanautapu Fonualei Sisia Katafanga Ovaka Taunga Taunga Ovaka Ta'uta S (85) (39) S " " 0 0 ' ' 5 5 4 4 ° ° 8 8 1 Avalau Mounu 1 Ngau Tokokafonua 'Euakafa Lekelela Fonua'unga Totokamaka 'Euaiki Lua'ui Fonuafo'ou -

An Assessment of the Skipjack and Baitfish Resources of the Kingdom of Tonga

AN ASSESSMENT OF THE SKIPJACK AND BAITFISH RESOURCES OF THE KINGDOM OF TONGA Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme Final Country Report No. 11 South Pacific Commission Noumea, New Caledonia September 1983 LIBRARY -2 DEC. 1983 AN ASSESSMENT OF THE SKIPJACK AND BAITFISH RESOURCES OF THE KINGDOM OF TONGA Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme Final Country Report No.11 South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia September 1983 iii PREFACE The Skipjack Survey and Assessment Programme was an externally funded part of the work programme of the South Pacific Commission. Governments which provided funding for the Programme were Australia, France, Japan, New Zealand, United Kingdom and the United States of America, and the generosity of these governments is gratefully acknowledged. The Skipjack Programme has been succeeded by the Tuna and Billfish Assessment Programme which is receiving funding from Australia, France, New Zealand and the-United States of America. The Tuna Programme is designed to improve understanding of the status of the stocks of commercially important tuna and billfish species in the region. Publication of final results from the Skipjack Programme, including results from the Programme's investigation of yellowfin tuna resources of the region, is continuing under the Tuna Programme. Reports for each of the countries and territories for which the South Pacific Commission works have been prepared in a final country report series. Most of these reports have been co-operative efforts involving all members of the Tuna Programme staff in some way. The staff of the Programme at the time of preparation of this report comprised the Programme Co-ordinator, R.E. -

IFAD Operations in the Kingdom of Tonga

Kingdom of Tonga Type of report: Mid-term Review Report Report No.: 3395-TO Date: 18 May – 5 June 2015 Briefing Paper IFAD operation in the Kingdom of Tonga 1 August 2017 2 Kingdom of Tonga Briefing Paper IFAD operation in the Kingdom of Tonga August 2017 Document Date: August 2017. Project No.: 1628 Document No.: 170317-TO Ministry of Finance & National Planning / IFAD Asia and Pacific Division / Mainstreaming of Rural Development Innovation Tonga Trust; 3 Table of Content 1. IFAD as an Organisation ……………………………………………………………….4 2. IFAD Strategic Frameworks for 2016-2025 ……………..……………………………4 3. IFAD Goal ………………………………………………….……………………………4 4. IFAD Objectives …………………………………………….…………………………..4 5. IFAD working in partnership to eradicate rural poverty.……..….…………………4 6. IFAD membership ………………………………………………………………………5 7. IFAD key people …………………………………………………….…………………5 8. IFAD operation in Asia and the Pacific ………………………………………………6 9. IFAD operation in Tonga ……………………………………………………………..7 9.1 Tonga Rural Innovation Project I …………………………………………….8 9.2 Outer Islands Credit Project …………………………………………………..9 9.3 Rural Credit Project ……………………………………………..…………….10 9.4 Agriculture Credit Project ………………………………….………………….11 10. Tonga Rural Innovation Project II ………………………………..………………12-21 4 International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD) The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), a specialized agency of the United Nations, was established as an international financial institution in 1977 as one of the major outcomes of the 1974 World Food Conference. The conference -

Kingdom of Tonga

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE BUILDING ON THE PAST KINGDOM OF TONGA STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 8 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN EIGHT 2006/07—2008/09 Strategic Development Plan 8 2006/07-2008/09 Table of Contents Page No. Map of Tonga vi Basic Information on Tonga vii Abbreviations viii Note x Minister’s Foreword xi 1 Development Performance and Reforms 1 1.1 Overview of Economic and Social Development 1 1.2 Economic and Public Sector Reforms in 2000-2005 3 1.2.1 SDP7 4 1.2.2 EPSRP 5 1.2.3 Environmental Conservation 12 1.2.4 Summary 12 1.3 Economic Performance, FY2000-FY2006 13 1.4 Key Observations for Planners 19 2 The People’s Perspective on Development 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Community Consultations 21 2.2.1 Tongatapu 21 2.2.2 Vava’u 23 2.2.3 Ha’apai 25 2.2.4 ‘Eua 27 2.2.5 Niuafo’ou 28 2.2.6 Niuatoputapu 29 2.3 Non-Government Organisations 30 2.4 Church Leaders 30 2.5 Private Sector 31 2.5.1 Consultation and Communication 31 2.5.2 Business Environment 31 2.6 Key Observations for Planners 31 3 National Development Vision and Goals 33 3.1 Development Challenges 33 3.2 Development Vision and Goals 34 3.3 Achieving SDP8’s Goals: A Summary of Strategies 40 Looking to the Future, Building on the Past ii Strategic Development Plan 8 2006/07-2008/09 4 Creating a Better Governance Environment 50 4.1 The Meaning of Governance 50 4.2 Tonga’s Governance Environment 50 4.3 Governance Strategies 52 4.3.1 Voice and Accountability 52 4.3.2 Government Effectiveness 52 4.3.2.1 Public Administration 52 4.3.2.2 Public Financial Management 55 4.3.2.3 Public Enterprise -

A Study of the Rain Water Harvesting of the Outer

A Study of Rainwater Harvesting in Tonga April 2010 A STUDY OF THE RAIN WATER HARVESTING OF THE OUTER ISLANDS REGIONS IN TONGA REPORT: FEBRUARY – MARCH, 2010 Simione Silapelu & Sione Faka’osi Tonga Association of Non Governmental Organisations (TANGO) And Tonga Community Development Trust (TCDT) Kingdom of Tonga 1 A Study of Rainwater Harvesting in Tonga April 2010 PREFACE As many of us involved in many years in promoting and strengthening the drinking water harvesting in Tonga began to share our experiences through working very closely with community, donor agencies and organizations, we discovered that serious questions were emerging about why the majority of the population of Tonga somehow need or prefer water from the tanks to drink more so than water from any other sources. One particular donor agency was very curious and requested a specific answer for this. The answer is pure and simple the people have confidence that rain water in the tank is “good” to drink. Water is life and life is water without a doubt. This commodity is for every living thing and human beings are included. This particular product can break or make a country financially, socially, and also politically. Therefore our individual experiences and notions are not enough for such an essential creation so we must begin to share and analyze the situation in depth to discover the trends and patterns of our work and knowledge of water and in particular the drinking water so that our future action may be relevant to the EU‐EDF9 Water Harvesting key objective that is for the population of the outer islands regions to have sufficient drinking water in time of drought.