The Painted Turtle Or the Egg?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys Picta)

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta) Class: Reptilia Order: Testudines Family: Emydidae Characteristics: The most widespread native turtle of North America. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The adult painted turtle female is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long; the male is smaller. The turtle's top shell is dark and smooth, without a ridge. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities. The subspecies can be distinguished by their shells: the eastern has straight-aligned top shell segments; the midland has a large gray mark on the bottom shell; the southern has a red line on the top shell; the western has a red pattern on the bottom shell (Washington Nature Mapping Program). Behavior: Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators. Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud at the bottom of water bodies. Reproduction: The turtles mate in spring and autumn. Females dig nests on land and lay eggs between late spring and mid- summer. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Diet: Wild: aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish Zoo: Algae, duck food Conservation: While habitat loss and road killings have reduced the turtle's population, its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. -

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

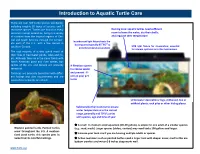

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina Rylen Nakama FISH 423: Olden 12/5/14 Figure 1. The Common Snapping Turtle, one of the most widespread reptiles in North America. Photo taken in Quebec, Canada. Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/yorthopia/7626614760/. Classification Order: Testudines Family: Chelydridae Genus: Chelydra Species: serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) Previous research on Chelydra serpentina (Phillips et al., 1996) acknowledged four subspecies, C. s. serpentina (Northern U.S. and Figure 2. Side profile of Chelydra serpentina. Note Canada), C. s. osceola (Southeastern U.S.), C. s. the serrated posterior end of the carapace and the rossignonii (Central America), and C. s. tail’s raised central ridge. Photo from http://pelotes.jea.com/AnimalFact/Reptile/snapturt.ht acutirostris (South America). Recent IUCN m. reclassification of chelonians based on genetic analyses (Rhodin et al., 2010) elevated C. s. rossignonii and C. s. acutirostris to species level and established C. s. osceola as a synonym for C. s. serpentina, thus eliminating subspecies within C. serpentina. Antiquated distinctions between the two formerly recognized North American subspecies were based on negligible morphometric variations between the two populations. Interbreeding in the overlapping range of the two populations was well documented, further discrediting the validity of the subspecies distinction (Feuer, 1971; Aresco and Gunzburger, 2007). Therefore, any emphasis of subspecies differentiation in the ensuing literature should be disregarded. Figure 3. Front-view of a captured Chelydra Continued usage of invalid subspecies names is serpentina. Different skin textures and the distinctive pink mouth are visible from this angle. Photo from still prevalent in the exotic pet trade for C. -

Leatherback Turtle New.Indd

Sea Turtles of the Wider Caribbean Region Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea General Description Nesting Distribution and Behavior The leatherback turtle, also known as the leathery Leatherbacks are the most migratory of the sea turtle or trunkback, is the largest and most distinctive turtles, are globally distributed, feed in temperate waters, of the sea turtles. and nest on tropical shores. The major Caribbean nesting beaches are in Trinidad and French Guiana. Other It is the only sea turtle which lacks a important sites are in Costa Rica, the Dominican hard, bony carapace (top shell), Republic, Puerto Rico, Suriname, the scutes and claws. Instead, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Venezuela. the leatherback has a rubbery “shell” The main Caribbean which is strongly nesting season begins tapered and char- in March and con- acterized by tinues to July. seven prominent Leatherbacks ridges. The back, like beaches head and fl ippers with deep, un- are often marked by obstructed access irregular blotches of and avoid abrasive rock white or pale blue. The or coral. The nesting plastron (bottom shell) ranges track width is 180-230 cm (82- from white to grey/black. The 92 in). Leatherbacks nest every dark upper and lighter lower surfaces 2-5 years or more, laying an average of in combination with the mottled coloration is 5-7 clutches per nesting season at 9-10 day effective camoufl age for this open-ocean inhabitant. intervals. Typically between 70-90 fertile (yolked) eggs The leatherback has a deeply notched upper jaw. are laid, as well as a variable number of smaller, infertile (yolkless) eggs. -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae. -

Conservation Biology of the European Pond Turtle Emys Orbicularis (L) in Italy 219-228 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stapfia Jahr/Year: 2000 Band/Volume: 0069 Autor(en)/Author(s): Zuffi Marco A. L. Artikel/Article: Conservation biology of the European pond turtle Emys orbicularis (L) in Italy 219-228 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Conservation biology of the European pond turtle Emys orbicularis (L) in Italy M.A.L. ZUFFI Abstract Key words The updated situation and knowledge Emys orbicularis, distribution, ecology, of the biology, ecology, behaviour and pro- conservation, Italy, tection of the European pond turtle, Emys orbicularis (L.) in Italy is presented and discussed in the light of conservation bio- logical issues. Stapfia 69, zugleich Kataloge des OÖ. Landesmuseums, Neue Folge Nr. 149 (2000), 219-228 219 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction In this last decade, a "Big Bang" of interest in Italian populations of E. orbiculans enabled Populations of Emys orbicularis in Italy are to build up a consistent data set. Information distributed mainly in coastal areas and inter- on biometry (Zum & GARIBOLDI 1995a, b), nal plains. Most regions of Italy have been systematics (FRITZ & OBST 1995; FRITZ 1998), mapped, but in some cases the information is population structure (KELLER et al. 1998; KEL- incomplete (Fig. 1, Societas Herpetologica LER 1999), space usage (LEBBOROM & CHELA - Italica 1996). An uncomplete knowledge of ZZI 1991), reproductive biology (ZUFFI & habitat use leads to a biased view on the ODETTI 1998; ZUFFI et al. 1999; KELLER 1999), and thermal ecology (Dl TRAM & ZUFFI 1997), have become available. -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Box Turtle (Terrapene Carolina) Phillip Demaynadier

STATE ENDANGERED Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) Phillip deMaynadier Description would most likely occur in the southwestern part of Box turtles are well-known for their remarkable the state. A few individual box turtles have been ability to seal themselves tightly in their shell during found in the last 20 years as far north as New times of danger. The box turtle is distinguished by a Vinyard in Franklin County and Hermon in brownish carapace (upper shell). Each scute (seg- Penobscot County, although these may have been ment of the shell) has yellow or orange radiating released pets. lines, spots, or blotches. The legs and neck have Box turtles are the most terrestrial turtle in the black to reddish-brown skin with yellow, red, or state. They prefer moist woodlands and wet, brushy orange spots and streaks. The plastron (lower shell) fields, especially where sandy soils are prevalent. Box is tan to dark brown. The box turtle’s most distinc- turtles occasionally are found in meadows, bogs, and tive feature is a hinged plastron, allowing the animal marshes. to withdraw its legs and head entirely within a tightly closed shell. Males have red eyes, a concave Life History and Ecology plastron, a thick tail, and long, curved claws on the Box turtles emerge from hibernation in late hind feet. Females have yellowish-brown eyes; a flat April or early May following the first warm spring or slightly convex plastron; a carapace that is more rains. They attain sexual maturity at 5-10 years old. domed than the male’s; short, slender, straighter Once they reach maturity, they mate anytime claws on the hind feet; and a shorter, thinner tail. -

Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys Picta Picta Description Painted Turtles Are Commonly Found Around Quiet Bodies of Water

WILDLIFE IN CONNECTICUT WILDLIFE FACT SHEET Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta picta Description Painted turtles are commonly found around quiet bodies of water. These brightly colored turtles gain their name J. FUSCO © PAUL from colorful markings along the head, neck, and shell. They often can be observed basking on logs and rocks around a body of water and will quickly scoot into water if threatened or disturbed. The medium-sized painted turtle can be distinguished by its dark shell, which has olive lines running across the carapace (upper shell), dividing the large scutes (scales). The margin of both the carapace and plastron (bottom shell) have black and red markings. The head, neck, and limbs have yellow stripes. The plastron is typically yellow, but may be stained a rust/red color. Males can be distinguished from females by their long front claws, long tail, and smaller size. The carapace of an adult usually measures from 4.5 to 6 inches in length. Range The painted turtle is the most widely distributed North basking on rocks and logs, even on top of one another. American turtle, and the only one to range across the Opportunistic, painted turtles can be found in brackish entire continent. This species ranges from coast to tidal waters and salt marshes. Much of their time is spent coast through the northern United States and southern concealed in submerged vegetation. The turtles spend Canada, south to the Gulf of Mexico from Louisiana to the winter hibernating in mud or decayed vegetation southwestern Alabama. on pond bottoms, emerging earlier than other turtles, The painted turtle is Connecticut's most numerous turtle typically in March.