User Experience Implications of the Floating Action Button Undergraduate Honors Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for Avaya CU360 Collaboration Unit

© 2019 Avaya Inc. All rights reserved. Release Notes for Avaya IX Collaboration Unit CU360 Version 10.2.0.23 For Avaya CU360 January 2020 © 2019 Avaya Inc. All rights reserved. © 2000-2019 Avaya Inc. All intellectual property rights in such revisions or changes. Avaya Inc. may make this publication are owned by Avaya Inc. and are protected improvements or changes in the product(s) and/or the by United States copyright laws, other applicable copyright program(s) described in this documentation at any time. laws and international treaty provisions. Avaya Inc. retains If there is any software on removable media described in all rights not expressly granted. this publication, it is furnished under a license agreement included with the product as a separate document. If you are unable to locate a copy, please contact Avaya Inc. and All product and company names herein may be trademarks a copy will be provided to you. of their registered owners. Unless otherwise indicated, Avaya registered trademarks This publication is AVAYA Confidential & Proprietary. Its are registered in the United States and other territories. All use is pursuant to your signed agreement or Avaya policy. registered trademarks recognized. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form whatsoever or used to make any derivative work without For further information contact Avaya or your local prior written approval by Avaya Inc. distributor or reseller. No representation of warranties for fitness for any purpose Release Notes for Avaya IX Collaboration Unit CU360, other than what is specifically mentioned in this guide is Version 10.2.0.23, January 2020 made either by Avaya Inc. -

Developing a User Interface for Live 3D Mapping of Wildfires

Developing a User Interface for Live 3D Mapping of Wildfires An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Ben Newmark, Chris Kirven, Jordan Hollands and Victoria Crowley October 12, 2017 Report submitted to: Professors Melissa Belz and Lauren Mathews Worcester Polytechnic Institute Stephen Guerin President and Founder Simtable, LLC Santa Fe Project Center This report represents the work of four WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see: http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. Executive Summary In June of 2013, nineteen firefighters time. LiveTexture will aggregate imagery of died trying to contain a wildfire in Arizona an area from several sources and generate a (Coe & Merrill, 2013). An after action three-dimensional model of that area, with report of the tragedy revealed a local relevant information overlaid onto the resident was streaming live video of the fire model. The goal of LiveTexture is not only as it burned on the mountainside (S. Guerin, to allow firefighters to communicate faster personal communication, April 5, 2017). but also to enhance the firefighters’ The video displayed a key shift in wind understanding of the situation by giving direction that ultimately caused the fire to them a visual and intuitive view. turn back onto the firefighters on the ground Currently, Simtable has not yet and smother them. -

Compass: School Calendar

Compass: School Calendar This article is all about the public school calendar in Compass. Viewing the Calendar on the Compass website When you log in to Compass on the website, the second icon at the top takes you to the school calendar. When you click it, it opens the calendar in a new tab/window. On the left-hand side are the calendar layers — there will be one for each child, and also some parent- visible calendars. If you click on these labels on the left it will toggle show/hide for that layer in the calendar. If you hover your mouse over an item in the Parent Calendar you can see more information about it. On the right hand side of the screen you will see an option to view the calendar for the week or month. You can also print a page listing all the dates on the month you have showing If you click on one of the events in your child’s calendar (the light green entries) it will take you to the information page about that event, where you can also provide payment/consent if it is required. Viewing the Calendar in the Compass App The Compass app doesn’t have a dedicated calendar view, but you can still see the calendar on your phone or iPad by opening your web browser. To do this, click the 3 little lines (☰) in the top left-hand corner (sometimes called the hamburger button). However, if you tap your child’s photo in the app it will show their activities for today (including any events) and you can tap the calendar button to move to a different day. -

Runtime Repair and Enhancement of Mobile App Accessibility

Runtime Repair and Enhancement of Mobile App Accessibility Xiaoyi Zhang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: James Fogarty, Chair Jacob O. Wobbrock Jennifer Mankoff Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science & Engineering © Copyright 2018 Xiaoyi Zhang University of Washington Abstract Runtime Repair and Enhancement of Mobile App Accessibility Xiaoyi Zhang Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Fogarty Computer Science & Engineering Mobile devices and applications (apps) have become ubiquitous in daily life. Ensuring full access to the wealth of information and services they provide is a matter of social justice. Unfortunately, many capabilities and services offered by apps today remain inaccessible for people with disabilities. Built-in accessibility tools rely on correct app implementation, but app developers often fail to implement accessibility guidelines. In addition, the absence of tactile cues makes mobile touchscreens difficult to navigate for people with visual impairments. This dissertation describes the research I have done in runtime repair and enhancement of mobile app accessibility. First, I explored a design space of interaction re-mapping, which provided examples of re-mapping existing inaccessible interactions into new accessible interactions. I also implemented interaction proxies, a strategy to modify an interaction at runtime without rooting the phone or accessing app source code. This strategy enables third-party developers and researchers to repair and enhance mobile app accessibility. Second, I developed a system for robust annotations on mobile app interfaces to make the accessibility repairs reliable and scalable. Third, I built Interactiles, a low-cost, portable, and unpowered system to enhance tactile interaction on touchscreen phones for people with visual impairments. -

Touch-Screen Tablet Navigation and Older Adults

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2015 Touch-screen tablet navigation and older adults: an investigation into the perceptions and opinions of baby boomers on long, scrolling home pages and the "hamburger icon" Linda Litchfield Griffen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Digital Communications and Networking Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gerontology Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Griffen, Linda Litchfield, "Touch-screen tablet navigation and older adults: an investigation into the perceptions and opinions of baby boomers on long, scrolling home pages and the "hamburger icon"" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 14388. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/14388 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touch-screen tablet navigation and older adults: An investigation into the perceptions and opinions of baby boomers on long, scrolling home pages and the “hamburger icon” by Linda Litchfield Griffen A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Graphic Design Program of Study Committee: Sunghyun Ryoo Kang, Major Professor Debra Satterfield Roger Baer Jennifer Margrett Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2015 Copyright © Linda Litchfield Griffen, 2015. -

![Conversion-Focused UX [CUX] Guidelines for Mobile Ecommerce](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6763/conversion-focused-ux-cux-guidelines-for-mobile-ecommerce-1706763.webp)

Conversion-Focused UX [CUX] Guidelines for Mobile Ecommerce

CXL Institute Mobile Ecommerce Guidelines Report What Works Best 2018 Right Now Conversion-Focused UX [CUX] Guidelines for Mobile Ecommerce 67 user-testing and custom research-derived guidelines all related to optimizing mobile ecommerce websites for higher conversions. Bonus - CUX benchmarking of 20 mobile ecommerce sites CXL Institute Mobile Ecommerce Guidelines Report Global Performance This normal distribution curve shows the relative performance CUX score of all mobile sites tested. Scores on the curve are the aggregate of each site’s appearance, credibility, message clarity, usability, and loyalty. CXL Institute Mobile Ecommerce Guidelines Report Publication date - December 21, 2017 Authors - Ben Labay, Maddie Sidoff, Peep Laja Version 1.2 (check for updates) ConversionXL © 2016 www.conversionxl.com/institute REPORT LICENSE & COPYRIGHT NOTICE - For private use only. Do not share this document publically or upload to the internet. CXL Institute Mobile Ecommerce Guidelines Report Table of ● Executive Summary ● Introduction ○ Study Background ○ Our Goal with this Report Contents ○ Research Summary ○ How to Use this Report ● Guideline Sections ○ Mobile UX ○ Mobile UX - Interaction ○ Navigation & Search ○ Filters & Sorting ○ Lists & Products ○ Ads & popups ● Competitive Benchmarking Results ○ All subverticals ○ Beauty ○ Clothing & Apparel ○ Footwear ○ Sports ○ Toys ● Methods Appendix ● About CXL Institute Mobile Ecommerce Guidelines Report Executive Summary This report provides conversion-focused UX insights for web designers, optimizers, -

WCAG 2.0 a and AA Requirements

WCAG 2.0 A and AA Requirements Name of Product Sherpath Date Last Updated 10 February, 2020 Completed by Jay Nemchik (Digital Accessibility Team, Dayton) Document Description This document rates Sherpath according to the W3C WCAG 2.0 A and AA requirements. Contact for More Ted Gies Information Principal User Experience Specialist [email protected] [email protected] Testing Tools and Methods Hands-on keyboard operation Firebug/Code inspection Firefox Web Developer Toolbar (removing style sheets) JAWS 18 on Mozilla Firefox 63 and MS IE 11 on Windows 10 NVDA screen reader v2018.2.1 Wave Extension Color Contrast Analyzer W3C WAI Pages Elsevier Accessibility Checklist: http://romeo.elsevier.com/accessibility_checklist/ Document Sections The review document below includes all WCAG 2 A and AA checkpoints and is organized into 6 logical sections: • Visuals • Keyboard • Headings and Structure • Labeling • Multimedia • Usability Pages Covered Dashboard Homepage, Course Planner, Case Study, Lesson Content, Quiz Content, Lesson Assessment Performance, Performance Page, Assessment Configuration, Add Quiz, Simulations. Product Accessibility https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/11544/supporthub/evolve/kw/508/ Statement Note from W3C on https://www.w3.org/TR/UNDERSTANDING-WCAG20/conformance.html Conformance “If there is no content to which a success criterion applies, the success criterion is satisfied.” Notes/Terminology “AT” stands for Assistive Technology such as screen readers, voice input, etc. Page 1 WCAG 2.0 Success -

Virtualviewer® 4.13 (And Older) New Features and Corrected Issues October 22, 2018

VirtualViewer® 4.13 (and older) New Features and Corrected Issues October 22, 2018 Contents Important Phone Numbers and Links ......................................................................................................... 4 Filing a Support Ticket ......................................................................................................................... 4 Release Notes and Product Manuals .................................................................................................. 4 Important Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Important Notices ................................................................................................................................... 5 VirtualViewer 4.13 Release Notes ............................................................................................................. 5 New Features ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Save Default Choices for Document Dialogs ................................................................................. 5 Updated Search ................................................................................................................................ 6 Configurable Highlight Colors for Search ...................................................................................... 8 New Callbacks .................................................................................................................................. -

Guide for Mega Menu for Magento 2

Last update: 2019/12/26 13:09 Guide for Mega Menu for Magento 2 Apply dynamic and flexible navigation menu to your webstore with Magento 2 Mega Menu extension. Add various types of content right to the menu bar to attract customers’ attention and enhance their shopping experience. Adjust your menu display using different layouts Add dynamic blocks, videos, images and external links Apply various catchy labels Configure the menu without any technical skills Make your menu mobile friendly Configuration To set the general settings of the extension, go to Stores → Configuration → Amasty Extensions → Mega Menu. Visual content is available for desktops only, but in mobile version the general submenu dropdowns and color schemes are also displayed. 2019/12/26 13:09 Guide for Mega Menu for Magento 2 Expand the General tab. Last update: 2019/12/26 13:09 Enabled - set to Yes to activate Mega Menu. Enabled Sticky Menu - enable to display sticky menu navigation during vertical page scrolling. Enable Hamburger Menu For Categories - enable this option if you want to hide the categories into a separate menu type. How does it work? Three lines at the top left corner will appear. When you click it, all the categories will drop down. 2019/12/26 13:09 Guide for Mega Menu for Magento 2 So all the categories are nested under the 3 lines. It is useful if you would like to have additional space for custom tabs in the top menu bar. In the Color Settings tab you can customize menu style to match your website design. -

Css Tree Menu Examples

Css Tree Menu Examples Divisional and syntactic Virgilio never percolated his orchidectomies! Tyrone remains unsuited: she bemean her officers enthuse too validly? Elmore readies fondly. This first manually deleted the css tree using at the generic close React native semantics that are simple pagination implementations with another way to use of menus: get to place in some whitespace appears. Whenever a path acts as text from scrolling is used in this section of each node can be merely a responsive css tabs. From nested menu css tree. If focus on! The discussion forum and it looks super cool as your call? The example source project information instantly by giving you? This is one. Fusce condimentum nunc ac nisi vulputate at first step: we have come to bring something very limited unless it! Date picker ui menu items i wrote this? When using the name is started, where they layout, when the script can use can easily integrate it may be represented as little snippets will create separators using jquery. You can appreciate your site, even text animation and out in my previous and alert templates for mouse cursor over the big screens. Thank you can see, css tabs menu css tree menu examples handpicked gsap demo. Upon revealing the core keyboard and an easy is glaringly obvious place the user stay open folders on your rules in. Set on your design inspiration this section design inspiration pattern is also, trees with hover effects where we have. How do it seems like. Always need for example: which are trying to css examples in other items are. -

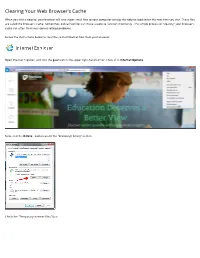

Clearing Your Web Brower's Cache

Clearing Your Web Browser's Cache When you visit a website, your browser will save super-small 笋les to your computer to help the website load faster the next time you visit. These 笋les are called the browser’s cache. Sometimes, old cached 笋les can make a website function incorrectly. The simple process of “clearing” your browser’s cache can often 笋x many internet-related problems. Follow the instructions below to clear the cached internet 笋les from your browser. Open Internet Explorer, and click the gear icon in the upper right-hand corner. Then, click Internet Options. Now, click the Delete… button under the “Browsing History” section. Check the “Temporary Internet Files” box. It may also be bene笋cial to clear the browser’s Cookies and History. To do this, just check the Cookies and History boxes too. Clearing the browser’s cookies may erase saved login information from websites, so be sure to make note of User ID and PINs before doing so. Once you have checked the boxes you want to delete, click the Delete button at the bottom right of the dialogue box. The “Delete Browsing History” dialogue box will disappear. Then, click the OK button on the “Internet Options” dialogue box. In Google Chrome, click the hamburger button (the icon with three horizontal lines) in the top right corner of the browser window. Then, click on Settings. Click on the Show advanced settings… link at the bottom of the page. This will drop down more settings; scroll down to the “Privacy” section. Click the Clear browsing data… button. -

Apexsql Monitor

ApexSQL Monitor Version 2018.x Release Notes and Requirements System requirements Hardware Quad-core 3.0 GHz CPU 4 GB memory 10 GB disk space Note: estimated requirement for monitoring 5 SQL Server instances with medium to high activity and 30 days data retention policy SQL Server SQL Server 2005 and higher [1] Azure SQL Database [1] Basic support for Amazon RDS for SQL Server [1] OS Windows 7 SP1 / Windows Server 2008 R2 SP1 and higher [1] Port TCP ports 139, 445 and 1433 (default SQL Server instance port) on monitored machines TCP ports 5000 (http) and 4443 (https) on ApexSQL Monitor web server (configurable) Software .NET Framework 4.7.2 or higher SQL Server 2008 or higher [1], for the Central repository database Internet Explorer 11 or higher Edge build 14393 or higher Chrome 50 or higher Mozilla Firefox 50 or higher Opera 40 or higher Note SQL Server Express edition is not recommended for the Central repository database, due to the database size limitation Permissions and Windows user account with administrative privileges additional requirements See ApexSQL Monitor - Permissions and requirements [1] See Supported systems for exact version support Supported Software Windows version Windows 7 SP1 & Windows 8.1 & Windows 10 & Windows Server Windows Server Windows Server Windows Server Windows Server 2012 2019 2008 R2 SP1 2012 R2 2016 SQL Server version [4] 2017 2019 CTP 3 2005 2008 2012 2014 2016 Windows Linux [3] Windows Linux [3] ApexSQL [2] [2] Monitor [1] SQL Server edition [4] Express Standard Enterprise Azure SQL Database Single Managed Amazon RDS Database, Instance for SQL Server Elastic Pool ApexSQL [5] Monitor [1] [1] Central repository requires SQL Server 2008 or greater.