Redalyc.Some Remarks on Mangroves in the Lesser Antilles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caribbean Caribbean

The Association of Former Students of Texas A&M Treasures of the CCaribbeanaribbean cruising the Windward Islands Grenada u St. Vincent and the Grenadines u Martinique u Iles des Saintes u St. Lucia u Barbados aboard the Exclusively Chartered, Five-Star Le Champlain Feb. 22-29, 2020 Y JULY E B 2 V 5, R 2 E 0 S EARLY 1 E 9 BOOKING R N N N N S A SAVINGS ! E V L E P $ U 2 , O 000 P E R C Howdy, Ags! Elude the depths of winter in the idyllic Windward Islands, a remote archipelago of dramatic volcanic peaks, lush gardens and white-sand beaches, the southern most islands of the Caribbean. Enjoy the intimate atmosphere of the exclusively chartered, Five-Star, small ship Le Champlain, featuring only 92 Suites and Staterooms, each with a private balcony—and the extraordinary Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory underwater Observation Lounge, for viewing the Caribbean’s abundant marine life through clear water. Experience exclusive access to small ports, picturesque islands and secluded bays and cays inaccessible to large ships—truly the best way to see the authentic Caribbean. Relax with warm tropical breezes amid turquoise waters and revel in the sublime charm of island life on Zodiac excursions to encounter the natural treasures of the Caribbean. This custom-designed, unique itinerary spans the boundlessly lush natural landscapes of the Windward Islands from Grenada to Martinique to Barbados. Visit Kingstown, home to the oldest botanic garden in the Western Hemisphere, and travel amid waving coconut palm trees alongside the Caribbean Sea on the most captivating isle of Bequia. -

Lowrie, K., M. Friesen, D. Lowrie, and N. Collier. 2009. Year 1 Results Of

2009 Year 1 Results of Seabird Breeding Atlas of the Lesser Antilles Katharine Lowrie, Project Manager Megan Friesen, Research Assistant David Lowrie, Captain and Surveyor Natalia Collier, President Environmental Protection In the Caribbean 200 Dr. M.L. King Jr. Blvd. Riviera Beach, FL 33404 www.epicislands.org Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 3 GENERAL METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Field Work Overview ........................................................................................................................... 4 Water‐based Surveys ...................................................................................................................... 4 Data Recorded ................................................................................................................................. 5 Land‐based Surveys ......................................................................................................................... 5 Large Colonies ................................................................................................................................. 6 Audubon’s Shearwater .................................................................................................................... 7 Threats Survey Method ................................................................................................................. -

Treasuresof the Caribbean

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Treasures OF THE Caribbean Sailing THE Windward Islands NORTH AMERICA Îles des Saintes UNESCO World Heritage Site Windward Cruise Itinerary Islands Air Routing SOUTH AMERICA Fort-de-France Martinique ST. VINCENT Rodney Bay AND THE Soufrière GRENADINES St. Lucia Kingstown St. Vincent Bequia Bridgetown Barbados St. George’s Tobago Cays Caribbean Sea Grenada February 26 to March 5, 2022 Barbados u St. Lucia u Îles des Saintes u Martinique Experience seafaring in its most timeless form on this St. Vincent and the Grenadines u Grenada custom-designed, seven-night cruise of the Caribbean’s 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada/ Arrive Bridgetown, Barbados/Embark Wind Star tropical Windward Islands aboard the exclusively 2 Rodney Bay, St. Lucia/Soufrière chartered Wind Star. This Five-Star, four-masted small sailing ship features all ocean-view accommodations. 3 Terre-de-Haut, Îles des Saintes Sail into secluded harbors inaccessible to larger vessels, 4 Fort-de-France, Martinique exploring the Windward Islands’ natural, cultural and 5 Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines/ Admiralty Bay, Port Elizabeth, Bequia historical treasures. Visit Grenada, the “Spice Island,” replete with historical landmarks and rare herbs; 6 St. George’s, Grenada Martinique’s rum distillery and Balata Gardens; St. Lucia’s 7 St. Vincent and the Grenadines/Tobago Cays majestic waterfall and volcanic Sulphur Springs; and 8 Bridgetown, Barbados/Disembark ship/ Return to the U.S. or Canada St. Vincent and the Grenadines, including Tobago Cays Itinerary is subject to change. Marine Park. Barbados Pre-Program Option is offered. Exclusively Chartered Five-Star Sailing Ship Wind Star Treasures of the Caribbean Included Features* On Board the Exclusively Chartered, Five-Star reserve early! Approximate Early Booking pricing from $3995 per person, Small Sailing Ship Wind Star double occupancy for land/cruise program. -

Treasures of Caribbean: Cruising the Windward Islands

distinguished travel for more than 35 years EMY ALUMN D I A CA S A S L O A C V IA A T N I O . S N OF THE . Treasures Caribbean U YEARS ALUMNI TRAVEL • THE E • X 2 Sailing Windward Islands PL 97 50O E 1 RING SINC NORTH AMERICA Îles des Saintes UNESCO World Heritage Site Windward Cruise Itinerary Islands Air Routing SOUTH AMERICA Fort-de-France Martinique ST. VINCENT Rodney Bay AND THE Soufrière GRENADINES St. Lucia Kingstown St. Vincent Bequia Bridgetown Barbados Saline Bay Mayreau St. George’s Tobago Cays Caribbean Sea Grenada February 26 to March 5, 2022 Barbados u St. Lucia u Îles des Saintes u Martinique Experience seafaring in its most timeless form on this St. Vincent and the Grenadines u Grenada custom-designed, seven-night cruise of the Caribbean’s 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada/ Arrive Bridgetown, Barbados/ tropical Windward Islands aboard the exclusively Embark Wind Star chartered Wind Star. This Five-Star, four-masted small 2 Rodney Bay, St. Lucia/Soufrière sailing ship features all ocean-view accommodations. 3 Terre-de-Haut, Îles des Saintes Sail into secluded harbors inaccessible to larger vessels, 4 Fort-de-France, Martinique exploring the Windward Islands’ natural, cultural and 5 Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines/ historical treasures. Visit Grenada, the “Spice Island,” Admiralty Bay, Port Elizabeth, Bequia replete with historical landmarks and rare herbs; 6 St. George’s, Grenada 7 Saline Bay, Mayreau, St. Vincent and the Grenadines/ Martinique’s rum distillery and Balata Gardens; St. Lucia’s Tobago Cays majestic waterfall and volcanic Sulphur Springs; and 8 Bridgetown, Barbados/Disembark ship/ St. -

SAINT LUCIA: a Case Study

UNCTAD National Workshop Saint Lucia 24 – 26 May 2017, Rodney Bay, Saint Lucia “Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation for Coastal Transport Infrastructure in Caribbean SIDS” SAINT LUCIA: A Case study By Isavela Monioudi University of the Aegean, Greece Vasantha Chase Chase Consulting Ltd., Saint Lucia This expert paper is reproduced by the UNCTAD secretariat in the form and language in which it has been received. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD. Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Transportation Infrastructure in the Caribbean: Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) SAINT LUCIA: A Case study Isavela Monioudi, Vasantha Chase Synopsis 1. Introduction 1.1 SIDS vulnerability to CV & C 1.2 CV & C impacts on transport/tourism 2. St Lucia country overview 2.1 Socio-economic profile 2.2 Climate projections 3. Transport infrastructure: Criticality 4. Description of major assets 5. Climate Variability and Change Impacts 5.1 Historical impacts/disruptions 5.2 Future impacts/disruptions 5.2.1 Methodology 5.2.2 Direct Impacts 5.2.3 Indirect Impacts 6. Conclusions 1 Scope of the study • SIDS are sea-locked and rely on the transport sector (especially airports & seaports). • Transport infrastructure is vulnerable to CV & C, especially in Caribbean SIDS. The scope of the present study is the assessment of the criticality of the major transportation assets of Saint Lucia and their potential vulnerabilities to Climate Variability and Change. SIDS vulnerability -

Treasuresof the Caribbean

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Treasures OF THE Caribbean Sailing THE Windward Islands NORTH AMERICA Îles des Saintes UNESCO World Heritage Site Windward Cruise Itinerary Islands Air Routing SOUTH AMERICA Fort-de-France Martinique ST. VINCENT Rodney Bay AND THE Soufrière GRENADINES St. Lucia Kingstown St. Vincent Bequia Bridgetown Barbados Saline Bay Mayreau St. George’s Tobago Cays Caribbean Sea Grenada February 26 to March 5, 2022 Barbados u St. Lucia u Îles des Saintes u Martinique Experience seafaring in its most timeless form on this St. Vincent and the Grenadines u Grenada custom-designed, seven-night cruise of the Caribbean’s 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada/ Arrive Bridgetown, Barbados/ tropical Windward Islands aboard the exclusively Embark Wind Star chartered Wind Star. This Five-Star, four-masted small 2 Rodney Bay, St. Lucia/Soufrière sailing ship features all ocean-view accommodations. 3 Terre-de-Haut, Îles des Saintes Sail into secluded harbors inaccessible to larger vessels, 4 Fort-de-France, Martinique exploring the Windward Islands’ natural, cultural and 5 Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines/ historical treasures. Visit Grenada, the “Spice Island,” Admiralty Bay, Port Elizabeth, Bequia replete with historical landmarks and rare herbs; 6 St. George’s, Grenada 7 Saline Bay, Mayreau, St. Vincent and the Grenadines/ Martinique’s rum distillery and Balata Gardens; St. Lucia’s Tobago Cays majestic waterfall and volcanic Sulphur Springs; and 8 Bridgetown, Barbados/Disembark ship/ St. Vincent and the Grenadines, including Tobago Cays Return to the U.S. or Canada Marine Park. Barbados Pre-Program Option is offered. Itinerary is subject to change. -

Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 291 Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles Fort-de-France, Martinique (France) 18–20 March 2019 UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 291 Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles Fort-de-France, Martinique (France) 18–20 March 2019 UNESCO 2020 IOC Workshop Reports, 291 Paris, September 2020 English only The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this publication and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information in this publication. However, neither UNESCO, nor the authors will be liable for any loss or damaged suffered as a result of reliance on this information, or through directly or indirectly applying it. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariats of UNESCO and IOC concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of the frontiers of any country or territory. For bibliographic purposes this document should be cited as follows: IOC-UNESCO. 2020. Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles. Fort-de- France, Martinique (France), 18–20 March 2019. Paris, UNESCO. (Workshop Reports, 291). Published in 2020 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP (IOC/2020/WR/291) IOC Workshop Reports, 291 page (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS page Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ -

Certified Tours and Excursions Calabash Cove Resort &

Certified Tours and Excursions Calabash Cove Resort & Spa January 13, 2021 Exodus Boat Charters Half Day Sight Seeing & Snorkel Charter Cruise along Saint Lucia’s west coast on a 31’ Bowen speed boat with retractable bikini canvas top. Leave from Rodney Bay Marina past Castries our capital, Marigot Bay one of the most beautiful bays in the Caribbean, through the colonial fishing village of Anse la Raye, then Canaries and on to Soufriere; home of the majestic Pitons declared by Oprah Winfrey as “One of the five places to see in your lifetime.” Swim and snorkel in the Marine Reserve then relax on board while you cruise back to Rodney Bay. Cost: US$650.00 from 1-6persons Time: 8:00am to 12:00pm or 1:00pm to 5:0pm / Duration: 4 hrs Tour is available daily with refreshments water, sodas, Beer and rum punch Transfers are not included Full Day Sight Seeing & Snorkel Charter Cruise down the picturesque coastline one a 31ft. Bowen Speed Boat are at leisure to choose your stops from a number of the island’s beautiful locations like Marigot Bay, one of the most sheltered bays in the Caribbean. Sail past some of the island’s vibrant fishing villages like Anse La Raye home to the famous Friday Night Sea food fiesta and Canaries. Your final stop along the coast is the Island’s former capital city the town of Soufriere. Dip beneath the surface into the pristine turquoise waters of St. Lucia from you Boat. Masks, Snorkels and Fins are supplied on board for your use as you dive down a host of colourful coral reefs. -

Visitor Arrivals Report

VISITOR ARRIVALS REPORT Stay Over Arrivals by Market (February, 2018) 18,000 16,000 14,000 12,000 10,000 8,000 No. Arrivals of 6,000 4,000 2,000 0 Rest of Rest of USA UK Caribbean Canada Germany France Europe World 2017 13,793 5,931 4,627 6,266 1,039 417 761 568 2018 15,680 6,462 4,697 6,187 999 230 746 535 Source: Saint Lucia Tourism Authority Research & Planning Department TOTAL STAY OVER ARRIVALS BY MONTH MONTH 2017 2018 ACT. CHG. % CHANGE January 31,649 32,755 1,106 3.5% February 33,402 35,536 2,134 6.4% TOTAL 65,051 68,291 3,240 5.0% Stay Over Arrivals, by Month 40,000 35,000 30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 No. of Arrivals of No. 10,000 5,000 0 January February 2017 31,649 33,402 2018 32,755 35,536 STAY OVER ARRIVALS BY MARKET (February 2017/2018) Markets 2017 2018 ACT.CHG. % CHANGE USA 13,793 15,680 1,887 13.7% UK 5,931 6,462 531 9.0% Caribbean 4,627 4,697 70 1.5% Canada 6,266 6,187 (79) -1.3% Rest of Europe 1,039 999 (40) -3.8% Germany 417 230 (187) -44.8% France 761 746 (15) -2.0% Rest of World 568 535 (33) -5.8% Total 33,402 35,536 2,134 6.4% Notes: 1. Rest of Europe includes among others, Holland, Italy, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland 2.This data is obtained from the international ED Cards 3. -

Guida St Lucia

Le guide di CaraibiOnline SAINT LUCIA www.stlucia.it Table of contents WHAT'S ST LUCIA LIKE..................................................................................... 3 PRACTICAL GUIDE 13 Geography and landscapes........................................................................... 3 Where to stay.............................................................................................. 13 Beaches and seaside.................................................................................... 3 Car rental/Taxi............................................................................................. 14 Activities and sports..................................................................................... 4 Restaurants................................................................................................. 14 Emerald forest of St Lucia ........................................................................... 5 Activities and sports..................................................................................... 15 A little bit of history...................................................................................... 5 Useful numbers............................................................................................ 16 St Lucia, an independent state...................................................................... 5 Culture and population................................................................................. 6 Economy.................................................................................................... -

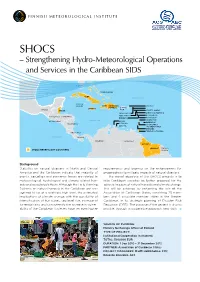

Strengthening Hydro-Meteorological Operations and Services in the Caribbean SIDS

SHOCS – Strengthening Hydro-Meteorological Operations and Services in the Caribbean SIDS FLORIDA THE BAHAMAS Gulf of Mexico CUBA Atlantic Ocean CAYMAN ISLANDS HAITI DOMINICAN VIRGIN IS. REPUBLIC PUERTO JAMAICA RICO MEXICO BELIZE ST. KITTS & NEVIS SAINT MARTIN ANTIGUA & BARBUDA GUADELOUPE GUATEMALA HONDURAS MONSTERRAT DOMINICA MARTINIQUE Carribean Sea SAINT LUCIA EL SALVADOR ARUBA BARBADOS CURACAO NICARAGUA ST. VINCENT & BONAIRE THE GRENADINES GRENADA TRINIDAD & TOBAGO COSTA RICA Pasific Ocean PANAMA COLOMBIA VENEZUELA GUYANA SURINAME FRENCH SHOCS BENEFICIARY COUNTIRES GUIANA Background Statistics on natural disasters in North and Central requirements and urgency on the enhancement for America and the Caribbean indicate that majority of preparedness to mitigate impacts of natural disasters. events, casualties and economic losses are related to The overall objective of the SHOCS projects is to meteorological, hydrological and climate related haz- help Caribbean societies be better prepared for the ards and associated effects. Although the Early Warning adverse impacts of natural hazards and climate change. Systems on natural hazards in the Caribbean are rec- This will be achieved by enhancing the role of the ognized to be at a relatively high level, the estimated Association of Caribbean States, consisting 25 mem- implications of climate change with the possibility of bers and 4 associate member states in the Greater intensification of hurricanes, sea level rise, increase of Caribbean, in its strategic planning of Disaster Risk torrential -

SEABOURN IS BACK in the CARIBBEAN 2021 Summer Voyages Open for Booking

SEABOURN IS BACK IN THE CARIBBEAN 2021 Summer voyages open for booking WORLD’S BEST BEST SMALL-SHIP BEST CRUISE BEST LUXURY GOLD BEST LUXURY MIDSIZE-SHIP CRUISE LINE LINE UNDER CRUISE LINE LIST CRUISE LINE OCEAN CRUISE LINE Condé Nast Traveler 1,000 BERTHS Luxury Travel Advisor US News & World Report Condé Nast Traveler Travel + Leisure Readers’ Choice Awards Guide Travel Weekly Awards of Excellence Readers Choice Our highest priorities are compliance, environmental protection, and protecting the health, safety and well-being of our guests, crew and the people in the destinations we visit. Visit Seabourn.com/TravelSafe to learn more. WE ARE EXCITED TO WELCOME YOU BACK TO YACHTING HARBORS AND TROPICAL COVES OF THE LEEWARD AND WINDWARD ISLANDS The wait is over. Join us on board Seabourn Odyssey this summer with new 7-day itineraries sailing round-trip Barbados. Or treat yourself to the ultimate Caribbean vacation experience and combine sailings for a 14-day combination voyage. From sparkling blue waters to white sand beaches, paradise awaits. Relax and rejuvenate as you enjoy our signature Caviar in the Surf®, Marina Day and Beach Barbecue along with the intuitive, personalized service only Seabourn can deliver. Jost Van Dyke Tortola “Have had 3 fabulous trips. Seabourn is the best!” St. Maarten – Libby H. St. itts Antigua 2021 SUMMER CARIBBEAN VOYAGES ON SEABOURN ODYSSEY CARIBBEAN YACHT ODYSSEY CARIBBEAN YACHT GEMS Round-trip Barbados | 7 Days Round-trip Barbados | 7 Days Jul 18; Aug 1, 15, 29; Sep 12, 26; Oct 10, Jul 25; Aug 8, 22; Sep 5, 19; Oct 3, 17, 24, 2021 31*, 2021 Bridgetown, Barbados Bridgetown, Barbados 1 Rodney Bay, St.