International Migration Outlook – Sri Lanka 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka Annual Performance

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS SRI LANKA ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2017 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Contents Page No 1. Mission, Subjects and Functions of the Ministry of Foreign 1 Affairs 2. Preface 3 - 5 3. Organizational Chart of the Ministry 7 4. Progress Report of the Divisions - Africa Division 9 - 27 - Consular Affairs Division 29 - 35 - East Asia and Pacific Division 37 - 80 - Economic Affairs and Trade Division 81 - 88 - European Union, Multilateral Treaties and Commonwealth 89 - 95 Division - Finance Division 97 - 102 - General Administration Division 103 - 106 - Legal Division 107 - 112 - Middle East 113 - 134 - Ocean Affairs and Climate Change Division 135 - 142 - Overseas Administration Division 143 - 149 - Overseas Sri Lankan Division 151 - 154 - Policy Planning Division 155 - 157 - Protocol Division 159 - 167 - Public Communications Division 169 - 172 - South Asia and SAARC Division 173 - 184 - United Nations and Human Rights Division 185 - 192 - United States of America and Canada Division 193 - 201 - West Division 203 - 229 5. Network of Diplomatic Missions Abroad 231 6. Revenue collected by Sri Lanka Missions Abroad in 2017 233 - 235 7. Consular activities carried out by Sri Lanka Missions Abroad - 236 - 238 2017 Vision To be a responsible nation within the international community and to maintain friendly relations with all countries. Mission The Promotion, Projection and Protection of Sri Lanka’s national interests internationally, in accordance with the foreign policy of the Government and to advise the Government on managing foreign relations in keeping with Sri Lanka’s national interests. Subjects and Functions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Implementation of political plans and programmes in respect of Foreign Affairs; Representation of Sri Lanka abroad; International Agreements and Treaties; Foreign Government and international organization’s representation in Sri Lanka; External publicity; Diplomatic immunities and privileges and Consular functions. -

Talks on for Producing Sinovac Vaccine Locally Organic Fertilizer For

Chemical fertilizer, pesticides and weedicides import ban confirmed ISHARA MUDUGAMUWA The Cabinet has approved Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s pro- posal as Finance Minister to sub- SRI LANKa’S NATIONAL NEWSPAPER I SINCE 1918 mit Import and Export (Control) WEDNESDAY JUNE 02, 2021 I 17 PAGES I VOLUME - 103 - NO 129 RS. 30.00 I REGISTERED AS A NEWSPAPER IN SRI LANKA I E-PAPER Regulations to implement the pro- posed ban on the import of chemi- cal fertilizer, pesticides and weedi- cides declared under the Imports and Exports (Control) Act No. 1 of 1969, to Parliament. Talks on for producing Sinovac vaccine locally Co-Cabinet Spokesman Mass Media Minister Keheliya Rambuk- MOHAMMED RASOOLDEEN the Daily News that initial discus- cination in Sri Lanka and the world for such vaccines on a daily wella said the Cabinet of Ministers Preliminary discussions were held sions were held on Tuesday at his production of vaccines in Sri basis. on April 27 this year, decided to in Colombo for the setting up of a Ministry to plan out the legal frame- Lanka, where it was decided that It was also felt that there is an ban importing chemical fertilizer, plant to manufacture the Chinese work needed for the establishment of the production of vaccines is the urgent need for the manufacture of pesticides and weedicides with the Sinovac COVID vaccines in Sri a manufacturing plant in Sri Lanka. best solution to end and control these vaccines because of the rising intention of promoting organic fer- Lanka. The focus of the discussions the pandemic successfully since prices of vaccines in all parts of the tilizer. -

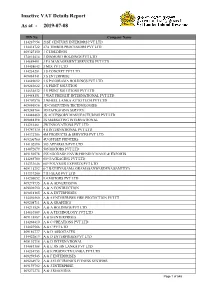

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Suspended Sentence Over Prison for Statutory Rape

www.themorning.lk LATE CITY VOL 01 | NO 01 | Rs. 30.00 { MONDAY } MONDAY, JANUARY 25, 2021 ‘THERE IS ABSOLUTELY NO DISCIPLINE IN THIS COUNTRY’ ILLUSION ART SL TARGETS A HISTORICAL, BREACHES THE $ 13 B EXPORTS SOCIOLOGICAL IN 2021 ANALYSIS LANKAN INTERWEBS »SEE PAGE 4 »SEE PAGE 10 »SEE PAGE 18 »SEE PAGE 15 Suspended sentence over GOSL to quantify prison for statutory rape z Proposals to allow underage love marriages and teen abortions in exceptional cases BY RUWAN LAKNATH JAYAKODY age of 16, has consented to of Justice Udaya Rohan De missing persons A legal amendment is sexual intercourse. Silva PC told The Morning. being drafted to change the If necessary, compensation Currently, Section 363(e) provisions in the Penal Code too can be ordered to be of the existing Penal Code, z Why now, Wigneswaran z Govt. duty is to find out what regarding statutory rape to paid in connection with the as amended through Act No. asks President happened: Dr. Paikiasothy allow for magistrates to offence. 22 of 1995, defines statutory be afforded the power to, “These alternatives, rape as “with or without her BY PAMODI WARAVITA However, Secretary to the allege that there are 40,000 depending on the individual proposed as amendments in consent when she is under The Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI) appointed Ministry of Foreign Affairs missing persons. This is a hugely circumstances of each such this regard, mean that young 16 years of age, unless the recently to probe the findings made by various previously Admiral Prof. Jayanath Colombage exaggerated and unsubstantiated case, grant suspended jail persons (understood in law to woman is his wife who is instituted commissions and committees of inquiry into told The Morning on 22 January figure. -

Mas Akansyčl Celebrates One Year in Haiti We Are Family

the active03rd Issue - September 2018 focuswww.masholdings.com AF SPOKE TO MAS ACTIVE LUSHAN MOTHER'S MAS AKANSYÈL WE ARE DAY 2018 CELEBRATES ONE FAMILY YEAR IN HAITI P-07 1 P-02 P-10 03rd Issue - September 2018 02 MAS Akansyèl we are one WE ARE MAS Akansyèl celebrates one year in Haiti 1 THE JOURNEY HAS JUST BEGUN... MAS Akansyèl, Haiti proudly is an intrinsic part of the MAS celebrated its 1-year anniversary Western Hemisphere footprint marking a significant milestone and to-date has created over 700 in the journey of MAS Active. direct jobs. Understanding customer needs and requirements has always The success of Haiti is directly helped MAS raise the bar and owed to the teams involved, make us front runners in the both based in Sri Lanka and apparel manufacturing arena. Haiti. MAS Akansyèl is a story which encompasses passion, MAS Akansyèl S.A, was commitment, hard work, incorporated in April 2017 collaboration and sacrifice! As and is situated within the Akansyèl turns one, we look Caracole Industrial Park in back at their journey thus far… Northern Haiti. MAS Akansyèl 03rd Issue - September 2018 03 we are one WHY HAITI Haiti’s consideration as a potential manufacturing location for MAS goes back to 2013, when Nike indicated interest in this location as it could offer preferential duty benefits and shorter lead-times. However, having visited the country, Nike decided it’s too perilous at the time to approve the location owing to several reasons. Then some years later, lululemon in 2016, in its endeavor to elevate the world from mediocrity to greatness, saw Haiti as a potential location to manufacture its premium products and invited MAS to partner them. -

Annual Report of the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation for the Year

1 P.O. Box : 2204 , Independence Square , Colombo 07 , Sri Lanka Telephone : 0112501050 -53 / 0112599505 – 9 Fax : 0112580131 Email : [email protected] Website : www.rupavahini.lk Y%S ,xld rEmjdyskS ixia:dj SRI LANKA RUPAVAHINI CORPORATION ,yq;if >h`pdpf; $l;Lj;jhgdk 2 To: Hon. Minister of Mass Media and Information We, the Chairman and the Members of the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation present herewith the Annual Report for the year 2011, in accordance with Section 14 (1) of the Finance Act No. 38 of 1971, along with the financial reports. On behalf of the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation, Mohan Samaranayake Chairman Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation Independence Square Colombo 07. 3 Vision To be the flagship broadcaster of all Sri Lankans Mission Achieve excellence in creative content and dissemination of timely and valued, educational, entertaining and informative programmes through dedicated team work and state-of-the-art technology to exceed the expectation of Sri Lankans everywhere. Aims To produce informative, educational and entertaining programmes while maintaining the highest standards and creativity To attract maximum number of viewers through excellent transmission To achieve financial stability and growth to run as a commercially viable autonomous state enterprise To protect the national identity of Sri Lankans the world over 4 Contents Message from the Chairman 6 The Board of Directors 8 The Senior Management 9 The Directors 10 Award Winning Achievements 11 Programmes Division 13 News and Current Affairs Division 24 Production Services Division 27 Engineering Division 36 Marketing Division 45 Administration Division 47 Airtime Analysis 54 Finance Division 58 Statement of Directors’ Responsibility 60 The Financial Report 61 The Audit Report 96 5 Message from the Chairman…. -

Di-P11-12-09-(P)

Tuesday 12th September, 2006 11 Is Sri Lanka women’s tennis wilting? Fact File Name: Jithmie Jayawickrema Born on June 7, 1991 School: Bishop’s College, Colombo Women’s National Champion 2005 and 2006 I’ll go on and Retained the title this year beating Amritha Muttiah in the final Present International Tennis Federation (ITF) U-18 World Rank: 962 The only child of Hirantha and Raji Jayawickrema Started Playing Tennis in 2000 Beginning of Career: Junior – Jithmie Beginners’ Squad at SL Tennis on ..... Association in 2000 by Revata S. Silva You’ve to win there to earn ITF ranking Coaches: Sylvester Francis (at he says it is difficult to hang on. points. You should be at least below 500 to school), Ganendran Subramaniam, Arul After winning two back-to-back sin- get a good foreign scholarship for tennis. Amalnathan, Shalini de Silva, Lasantha S gles titles in women’s nationals, So, it’s only now that I face the toughest Fernando and Chrishantha Perera S (SLTA Advanced Squad) this 15-year-old Bishopian says it’ll be a times,” Jithmie told “The Island” last two way fight from here for her: for spon- week. Achievements in SL Junior and sorship and for international ranking “I was the 4th seed when I won the Senior Nationals: points. The young Jithmie Jayawickrema nationals last year. It was very satisfy- U-12 winner in 2001 and 2002, and her parents, who sweated to make ing,” said the agile youngster. “But the U-14 runner-up in 2004 and 2005, their only child a champion tennis player pressure was immense this time as I was U-16 winner in both singles and dou- after four or five years of hard work, have the top seed. -

Events Calendar 2020

EVENTS CALENDAR 2020 No Event Name Date Venue Event Promoter/ Description of the Event Organizer 01 Colombo Marathon 05th January Colombo NEB Sports (PVT)LTD ● NEB sports PVT LTD is an organization which conducts and promotes 2020 Sports in India ● Colombo Marathon is conducts for promote tourism in country as well as to promote health and fitness in urban lifestyle. 02 Duruthu Perahera 07th – 09th Kelaniya Raja Sri Kelaniya Raja Maha ● The Duruthu Perahera is one of the most culturally glorious celebrated 07th – 9th January January Maha Viharaya Viharaya, by devotees annually during the month of January. 2020 2020 Kelaniya ● This event is primarily focused on showcasing the unique culture and heritage of Sri Lanka. ● This event will consist of three processions which will happen at night on three consecutive days. ● Many tourists and locals arrive to watch the parade since it is held in a suburb of Colombo. ● The Perahera is broadcasted via local and international media. 03 Navam Perahera 07th & 08th Gangaramaya Gangaramaya Temple ● Navam Maha Perahera happens to be the most colorful and prestigious 07th & 08th February Temple Buddhist cultural pageant held in Sri Lanka. Navam Maha Perahera is February 2020 2020 Tel:0112327084 celebrated once a year. Navam Maha Perahera is one of the most important religious and cultural events in Sri Lanka. 1 | P a g e ● Millions of people witness this Navam Maha Perahera event every year, Email:gt@gangaramaya including an estimated 10,000 tourists who land in Colombo during .com Navam Maha Perahera event. ● The highlight of this festival is the colorful elephant pageant when the Web:www.gangaramay streets of Colombo transform under the weight of 100 decorated a.com elephants. -

Aviation College

VOICE AVIATION 1 aviationvoiceblog.blogspot.com www.aviationvoice.lk www.facebook.com/AviationVoice Explore the skies with a World Class Qualification in Aviation Aliated to Kingston University - London Private Pilot Licence - PPL Commercial Pilot Licence - CPL Airline Transport Pilot Licence - ATPL Colombo Airport, Ratmalana. Information Centre, N0.14, Trelawney Place, Colombo 04, Sri Lanka. Tel. +94 11 451 0303/4, Fax: +94 11 451 0303 Email: [email protected] Contents Aircraft 5 Marshalling EDITORIAL BOARD Managing Editor Chathura Ranaweera Consultancy Sky Fiesta 2015 12 H. L. G. Saminda Saluka (English) Deputy Editors Aviation alphabet N. Nusha Gaffoor Gayanga Wijesena Vindya Niyangama 14 Janisha Gunarathne Lankesh Hesudeera Contributors Suhara De Fonseka It’s all hot air Anjalee Edirisinghe 19 Weemansa Dias Sathya Wijewardena Learning to Benuri Wickramarathne Kalani Wickramasinghe fly 21 Marketing & Advetising Tharaka Jayathilake Photography The flight back home Chandika Lakmal from Lahore 22 Lahiru Gurusinghe Kasun Prabath Sri Lankan Women Design in Aviation Banuka Sachintha 30 Print Neo Graphics Flight of The Publisher Aviation Voice 27 Double Sunrise No: 263B, Stanley Tillekeratne Mawatha, Nugegoda. T/P : 0711 277 769/ 0766 769 111 46 Email : [email protected] Web : www.aviationvoice.lk FB : www.facebook.com/AviationVoice Blog : aviationvoiceblog.blogspot.com VOICE SriLankan g+ : plus.google.com/+AviVoice AVIATION Aviation College twitter : twitter.com/Aviation_Voice 5 aviationvoiceblog.blogspot.com www.aviationvoice.lk www.facebook.com/AviationVoice Aviation Voice was fortunate to have Mr. H M C Nimalsiri, Director General of Civil Aviation Authority of Sri Lanka grace the occasion as the Chief Guest. Aviation Voice is a voluntary group A large number of invitees related who are working so hard in aviation to aviation industry, students from to prepare our next generation in Sri various schools and a general crowd Lanka to lead the aviation industry. -

COVID-19 Regulations Toughened

Failure to arrest Bathiudeen AG tells CID DIG to FRIDAY 16 october 2020 uphold rule of law LATEST EDITION VOL: 09/254 PRICE : Rs 30.00 BY HANSI NANAYAKKARA Attorney General (AG), Dappula de Livera has given instructions In Sports to the DIG in charge of the CID, to take measures to always uphold Sri Lankan-Venezuelan the rule of law and to act in a manner in which the public could couple in action place their implicit trust in them, in Poland rather than acting in a manner that would result in the trust Sri Lanka and South Asian record being lost. holder of the women’s Marathon, This was said by the AG’s Hiruni Keshara Wijayaratne, made Coordinating Officer, State yet another unusually long journey to Counsel Nishara Jayaratne,... Gdynia Poland on... A16 Story Continued on PAGE 2 Using Intel Units to trace COVID-19 infected National Security COVID-19 not jeopardised – Army Chief Regulations Army Commander Lt Gen Shavendra Silva said the use of Intelligence Units to detect COVID-19 infected persons throughout the country will in no way leave National Security in jeopardy. “Ensuring national security does not mean soldiers being deployed at strategic places, Toughened brandishing firearms. There are several aspects to national security. Some of those aspects are food security, power security, political protection, war security, environmental security and cyber security. Minister signs Authorities enabled What the Army does is to look into aspects such as the security side of things. Health protection also Special Gazette to prosecute violators falls under national security. -

FR Page 5.Qxd

Wednesday 08th September, 2010 Travel The Island Page 5 FFeeleel SriSri Lanka...Lanka... Sizzling Shanghai Hot Pot Promotion at Cinnamon Grand Imagine a sizzling hot pot placed in front of you with the opportu- nity to create a feast of flavours from an assortment of imported items! The Cinnamon Grand brings you this one-of-a-kind experi- ence with its Shanghai Hot Pot Promotion held from the 9th to the 19th of September at The Courtyard. Toss in seasoned meats sliced to perfection and fresh seafood into a simmering broth brimming with aromatic herbs and exotic vegetables. At just Rs. 1250/-+++, this unique hands-on promotion gives patrons a taste of distant Shanghai, right here in Colombo. The hot pot cooking method is simple but results in an abundance of flavour and taste, according to the various spices, sauces, oils and condiments used. Frozen meat is sliced deli-thin to prepare it for hot pot cooking. Slicing frozen meat this way causes it to roll up during cooking, and it is often presented as such. Meat or vegetables are loaded individually into the hot cooking broth by chopsticks, and cooking time is brief. Meat often only takes 15 to 30 seconds to cook. Guests can place items into the hot pot at a relaxed, leisurely pace, enjoying the cooking process, or throw everything in at once and wait for the hotpot to return to a boil. The Chinese hot pot boasts a history of more than 1000 years. Hot pot cooking seems to have spread to northern China during the Tang Dynasty. -

Trinity Takes Milo Trophy to the Hills Kingswood to Form Past Cricketers

Tuesday 7th October 2008 15 Mahanama College Ananda College Front row from left: Udaka Supun, Chathura Fernando, Oshan Chandula, Sajith Ruberu, Randika Welikannage. Front row from left: Udesh Nadeeranga, Geshan Wimaladharma, Lucky Rogers (Coach), Sachin Devage, Matheesha Second row from left: Manjuka Perera (Asst Coach), Rusiru Dilshan, Hashan Perera, Chanuka Rupasinghe, Perera (Captain), Priyankara Nandasena (MiC), Rasith Jayaratne, Aravinda Amarasekara (Asst. Coach), Minura de Silva. Danushka Gunathilaka, Lahiru Weerakoon, Aravinda de Silva, Pasindu Madushan, Dulan Chathuranga, Lesley Standing from left: Ruvinda Shamen, Asanka Ranthilakage, Sachithra Perera, Thisura Godahewa, Naleen Silva, Mayuka Harischandra (MiC) and Vipul Sittimige (Coach) Perera, Sanjeewa Udawatte, Tharaka Palihakkara, Chamith Deemantha and Pasindu Madushan. (Pic by Sajith Jayasekara) (Pic by Nishan S. Priyantha) Under-17 Division I Tournament Ananda-Mahanama clash for plum by Reemus Fernando they beat Kegalu Vidyalaya, In the absence of Jayaratne, left St. Benedict’s College to 130 runs to And the teams batting first have Dharmapala College, Pannipitiya arm paceman Ruvinda Shamen will earn a 43 run victory. struggled to score runs. Teams bat- A formidable Ananda College will and Thurstan College in a row to spearhead the attack with Sanjeewa On both occasions, the outstand- ting second have won four matches. meet Mahanama College in the earn their final spot. The most Udawatte and Thisara Kanishka. ing performance of all rounder And the only teams to have won the grand final of the Inter School remarkable victory during that stage Their spin department is strength- Danushka Gunathilaka was the key match after batting first are Under-17 Division I Tournament was their win against Dharmapala, ened by Minura Janadhi, Matheesha to the wins.