Benarkin National Park Management Statement 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GWQ4164 Qld Murray Darling and Paroo Basin Groundwater Upper

! ! ! ! ! ! 142°E 144°E 146°E 148°E ! 150°E 152°E A ! M lp H o Th h C u Baralaba o orn Do ona m Pou n leigh Cr uglas P k a b r da ee e almy iver o Bororen t Ck ! k o Ck B C R C l ! ia e a d C n r r r Isisford ds al C eek o r t k C ek Warbr ve coo Riv re m No g e C ecc E i Bar er ek D s C o an mu R i ree k Miriam Vale r C C F re C rik ree ree r ! i o e e Mim e e k ! k o lid B Cre ! arc Bulloc it o Cal ek B k a k s o C g a ! reek y Stonehenge re Cr Biloela ! bit C n B ! C Creek e Kroom e a e r n e K ff e Blackall e o k l k e C P ti R k C Cl a d la ia i Banana u e R o l an ! Thangool i r ive m c i ! r V n k n o B ! C ve e C e e C e a t g a o e k ar Ta B k Cr k a na Karib r k e t th e l lu o n e e e C G Nor re la ndi r B u kl e e k Cre r n Pe lly e c an d rCr k a e a M C r d i C m C e Winton Mackunda Central W y o m e r s S b re k e e R a re r r e ek C t iv Moura ! k C ek e a a e e C Me e e Z ! o r v r r r r r w e l r h e e D v k i e e ill Fa y e R C e n k C a a e R e a y r w l ! k o r to a C Bo C a l n sto r v r e s re r c e n e o C e k C ee o k eek ek e u Rosedale s Cr W k e n r k in e s e a n e r ek k R k ol n m k sb e C n e T e K e o e h o urn d o i r e r k C e v r R e y e r e h e e k C C e T r r C e r iv ! W e re e r e ! u k v Avondale r C k m e Burnett Heads C i ing B y o r ! le k s M k R e k C k e a c e o k h e o n o e e o r L n a r rc ek ! Bargara R n C e e l ! C re r ! o C C e o o w e C r r C o o h tl r k o e R r l !e iver iver e Ca s e tR ! k e Jundah C o p ! m si t Bundaberg r G B k e e k ap Monto a F r o e e e e e t r l W is Cr n i k r z C H e C e Tambo k u D r r e e o ! e k o e e e rv n k C t B T il ep C r a ee r in Cre e i n C r e n i G C M C r e Theodore l G n M a k p t r e Rive rah C N ! e y o r r d g a h e t i o e S ig Riv k rre olo og g n k a o o E o r e W D Gin Gin co e re Riv ar w B C er Gre T k gory B e th Stock ade re Creek R C e i g b ve o a k r k R e S k e L z re e e li r u C h r tleCr E tern re C E e s eek as e iv i a C h n C . -

South Burnett Health Service District Area

STAY ACTIVE, STAY INDEPENDENT StayStay OnOn YourYour FeetFeet Community Action Plan 2003-2006 SOUTHSOUTH BURNETTBURNETT DISTRICTDISTRICT COMMUNITIESCOMMUNITIES “STAY ON YOUR FEET” Central Public Health Unit Network – Wide Bay (CPHUN-WB) PO Box 724 HERVEY BAY QLD 4655 Ph: (07) 41977252 Fax: (07)41977299 THE STAY ON YOUR FEET TEAM: Darren Hauser (Project Manager) Ph: (07) 41977277 Email: [email protected] Sue Jones (Project Officer) Ph: (07) 41977265 Email: [email protected] Sue Volker (Administration Officer) Ph: (07) 41977252 Email: [email protected] Stay On Your Feet is funded by Injury Prevention and Control (Australia) Ltd. Injury Prevention and Control (Australia) Ltd has received grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council and Queensland Health (Quality Improvement Enhancement Program and Health Promotion Queensland) to assist in this project. STAY ON YOUR FEET COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN SOUTH BURNETT DISTRICT COMMUNITIES SECTION 1 : INTRODUCTION Page 3 FOCUS AREA: PUBLIC SAFETY Page 15 What is Stay On Your Feet all about? 1. Advocate for improved Public Safety How was this Community Action Plan developed? 2. Develop and support local awareness-raising activities What happens now? FOCUS AREA: HOME SAFETY Page 16 SECTION 2 : KEY STRATEGIES Page 9 1. Promote and support Home Safety audits (confirmed by all Local Planning Groups) 2. Promote information on Home Safety assistance 3. Promote education about home safety FOCUS AREA: AWARENESS AND INFORMATION Page 9 1. Coordinate, distribute and promote Awareness and FOCUS AREA: MEDICATIONS Page 17 Information resources 1. Encourage review of Medications 2. Train and support Stay On Your Feet Ambassadors 2. -

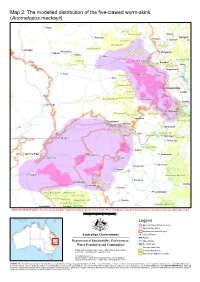

The Modelled Distribution of the Five-Clawed Worm-Skink (Anomalopus Mackayii)

Map 2: The modelled distribution of the five-clawed worm-skink (Anomalopus mackayii) Injune Koko SF Allies Creek SF Kilkivan Wandoan Proston Gympie Jarrah SF Goomeri Barakula SF Wondai SF Gurulmundi SF Mitchell Wallumbilla Roma Diamondy SF Kingaroy Yuleba Nudley SF Miles Chinchilla Conondale FR Yuleba SF Jandowae Blackbutt Bunya Mountains NP Kilcoy Benarkin SF Toogoolawah Surat Braemar SF Dalby Esk Tara Kumbarilla SF Toowoomba Dunmore SF Laidley Western Creek SF Boondandilla SF Millmerran Boonah St George Main Range NP Warwick Whetstone SF State Forest Durikai SF Border Ranges NP Inglewood Goondiwindi Toonumbar NP Boggabilla Yelarbon Stanthorpe Dthinna Dthinnawan CCAZ Texas Girraween NP Sundown NP Wallangarra Mungindi Girard SF Tenterfield Torrington SCA Ashford Lightning Ridge Moree Deepwater Collarenebri Warialda Glen Innes Inverell Bingara Walgett Guy Fawkes River NP Bundarra Wee Waa Mt Kaputar NP Dorrigo Narrabri Barraba Pilliga West CCAZ Pilliga CCAZ Armidale Pilliga East SF Pilliga West SF Euligal SF Pilliga East CCAZ Manilla Timallallie CCAZ Oxley Wild Rivers NP Coonamble Baradine Pilliga NR INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool at www.environment.gov.au/epbc/index.html km 0 20 40 60 80 100 Legend Species Known/Likely to Occur Species May Occur Brigalow Belt IBRA Region ! Cities & Towns Roads Major Rivers Perennial Lake ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! !! ! !! ! Non-perennial Lake Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN) Conservation Areas COPYRIGHT Commonwealth of Australia, 2011 Forestry & Indigenous Lands Contextual data sources: DEWHA (2006), Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data CAVEAT: The information presented in this map has been provided by a range of groups and agencies. -

Font: Times New Roman, 12Pt

Question on Notice No. 1854 Asked on 22 November 2005 MRS PRATT asked the Premier and Treasurer (MR BEATTIE)— QUESTION: Will he provide details of all Government grants for the Nanango Electorate by category for 2003, 2004 and 2005? ANSWER: To provide information on all Government grants within the Nanango Electorate would be an onerous process drawing resources from essential services. However, I have provided the following details on grants that have been made to assist the people of your electorate under my portfolio. Funding is allocated by financial year and the data has been provided in this format. 2002-03 (Rounded to nearest thousand) Minor Facilities Program 2002 Upgrade of four tennis courts from antbed to synthetic grass surface at Kingaroy - Kingaroy And District Tennis Association Inc - $56,000. Club Development Program 2002 Wide Bay Branch come and try days - Queensland Netball Association Wide Bay Branch Inc. - $3,000; Chicks claim their cattle - South Burnett Branch - The Australian Stock Horse Society Inc. - $3,000; Cricket coaching clinics - Kumbia Cricket Association Incorporated - $3,000; Intro to soccer comp - South Burnett Soccer Association Inc. - $3,000; South Burnett rugby recruit - South Burnett Rugby Union Club Incorporated - $3,000; Nanango netball junior development camp -Nanango And District Netball Association (Inc)- $3,000; Come 'n try fun days - South Burnett Branch Little Athletics Centre Inc. - $2,000; and Cactus program - Kingaroy Touch Association Inc - $1,000. Gambling Community Benefit Fund Purchase -

111Th Nanango Show

111111thth NanangoNanango ShowShow th Saturday the 18 of April 2020 CelebratingSaturday Youth the 18th of April 2020 Our hope for the Future 1 THE NANANGO AGRICULTURAL, PASTORAL AND MINING SOCIETY INC The Management Committee of the Nanango Agricultural, Pastoral & Mining Society Inc. would like to take this opportunity to welcome His Excellency the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Governor of Queensland, his wife Mrs. de Jersey, our Member of Parliament Mrs. Deb Frecklington, our Patron Mrs. Gloria Fleming, invited guests, Show Society Members and all other visitors to our 111th Annual Show to be held on Saturday 18th April 2020. We are looking forward to bringing you an entertaining day that caters for all ages. Whilst we strive to maintain our Agricultural Heritage, we continually work to ensure that the event is relevant for all visitors. Once again, the traditional features will be present: Pavilion & Trade Displays, Livestock & Horse Events, Rodeo Events, Wood Chopping Events, Post Splitting, the night time Fireworks and the fun filled Side Show Alley. There will be plenty of Food Stalls available throughout the show grounds, providing a variety of food and drinks to tempt your taste buds. This year, Harness Racing and Luke’s Snake Kingdom will be feature attractions. The initial stage of the Queensland Miss Showgirl Quest and the Rural Ambassador Award will be held in conjunction with our annual Show. The Pavilion Junior Judges and the Stud Beef Young Judges & Handlers competition will be held again this year. Exhibitors submitting entries in the Pavilion Section this year, will not be required to pay an entry fee due to the sponsorship from IGA Nanango. -

Brisbane Valley Rail Trail – Linville to Blackbutt

For your safety and comfort • Do not use the trail in extreme weather conditions. Code of conduct • Be cautious at all road and creek crossings. When using the trail, respect other users, the natural • Cyclists and horse riders must dismount at road crossings. environment and the privacy of adjacent landholders. • Cyclists and horse riders must wear an approved helmet and Sharing ride in control. • Do not approach pets or livestock in adjacent properties. • Park in designated areas. • Beware of swooping magpies in springtime. • Please leave all gates as found. • Carry drinking water and light snacks. • Observe local signs and regulations. • Wear appropriate clothing for the conditions. • Do not obstruct the trail. • Maintain your equipment, and carry repair and first-aid kits in www.dilgp.qld.gov.au/bvrt • Cyclists must alert other users on approach and pass at a case of emergencies. reduced speed. • Where possible, don’t travel by yourself. • Give way to horses and approach them with care. • Let someone know where you are going and when you expect • Keep dogs under control and on a lead. to return. • Jogging pace only. Emergencies 000 Environment State Emergency Services 0418 193 815 • Keep on the Rail Trail. For more information On the • Do not interfere with native plants or animals. Blackbutt Visitor Information Centre • Take your rubbish home with you. Hart Street, Blackbutt 07 4163 0633 • Clean up after your dog. Esk Visitor Information Centre • Do not light fires. 82 Ipswich Street, Esk 07 5424 2923 • Clean bikes, walking boots and other equipment after your right track trip to minimise the spread of plant and animal pests and Fernvale Futures and Visitor Information diseases. -

Southern Inland Queensland Visitor Guide

Department of National Parks, Recreation, Sport and Racing Visitor guide Featuring Bunya Mountains National Park Yarraman State Forest The Palms National Park Benarkin State Forest Ravensbourne National Park Crows Nest National Park Lake Broadwater Conservation Park Main Range National Park Girraween National Park Sundown National Park Balancing boulders and rugged gorges, rainforest-clad mountains and grassy plains, waterfalls and wetlands await discovery just a few hours inland from the beaches and busy cities of southern Queensland. Great state. Great opportunity. Secluded McAllisters Creek, Sundown National Park. Photo: Robert Ashdown Robert Photo: Welcome to Southern Inland Indigenous Australians have a long and ongoing relationship with many Queensland areas that are now national park or State forest. We acknowledge their important connection with country and ask that you treat the places you visit with care and respect. Whether for a short stroll or longer hike, a day trip or overnight stay, Queensland’s southern inland parks and forests are easy to get to and outstanding places to visit. Photo: Ken Chapman Ken Photo: Use this guide to help plan your trip. Each park or forest is different from the others, but all offer something special—from scenic views or distinctive features and wildlife, to glimpses into the past. Visitor facilities Camping Caravan/ Campervan Lookout and opportunities Dogs allowed allowed Dogs (on leash) Park office Park Toilets On-site information water Drinking shed Shelter table Picnic barbecueElectric barbecue/ -

Coal in Kingaroy

Coal in Kingaroy Briefing note A coal project proposed near Kingaroy, Queensland, is unlikely to provide benefit in a local economy based on services and agriculture. It imposes uncertainty and costs on other industries and the community. Policy makers should rule the project out on economic grounds. Tony Shields Rod Campbell Travis Hughes February 2019 Coal in Kingaroy 1 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute aims to foster informed debate about our culture, our economy and our environment and bring greater accountability to the democratic process. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. -

Discover South Burnett Tent and Trailer Based Camping

A step back in time Activities Roy Emerson Museum Brisbane Valley Rail Trail 31 Bowman Rd, Blackbutt 07 4163 0146 The longest rail trail in Australia, the Brisbane Valley The Roy Emerson Museum celebrates the Rail Trail (BVRT) is 161km in length, running from achievements of this locally-raised, international Yarraman in the North to Wulkuraka in the South. tennis champ. The adventure trail winds its way up the Brisbane Housed in the original Nukku State School where valley, uncovering a new experience around each tennis great Roy Emerson completed his primary bend. With breathtaking landscapes, open forests, years, are the photos and stories behind his unique country towns and local attractions awaiting success. to be discovered. Being on the old railway line, the BVRT can be accessed by horse, bike or on foot. Completing the collection is a selection of photos Suitable for day trippers, overnight camping or longer and memorabilia from the days of local timber term adventures. getting, early schooling, farming and the building of the railway. Les Muller Park Hart Street, Blackbutt Benarkin State Forest Authentic slab hut and wagon are the highlight of this local park. Located in the heart of town close to Take a scenic forest drive to picnic, camp, ride or walk shops and amenities this park features BBQ under towering forest trees or spot platypus in the facilities, picnic tables and a playground. local creek. Located on the Blackbutt Range the Benarkin State Kingaroy Visitor Information Centre Forest is a great spot to explore the natural rainforest, 128 Haly Street, Kingaroy hoop pine plantations and eucalypt forests. -

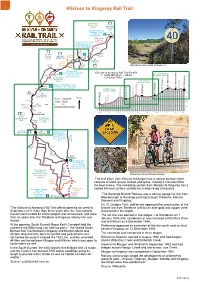

Kilkivan to Kingaroy Rail Trail

2 Kilkivan to Kingaroy Rail Trail Old railway sign south of Goomeri Sealed section by Denise Keelan The first 45km from Kilkivan to Murgon has a natural surface which consists of sand, gravel, ballast and grass, making a mountain bike the best choice. The remaining section from Murgon to Kingaroy has a sealed bitumen surface suitable for a wide range of bicycles. “The Nanango Branch Railway was a narrow-gauge rail line from Maryborough to Nanango passing through Theebine, Kilkivan, Goomeri and Kingaroy. On 31 October 1882, parliament approved the construction of the “The Kilkivan to Kingaroy Rail Trail official opening occurred in branch line from Theebine to Kilkivan after gold and copper were September 2017 more than three years after the Queensland discovered in the region. Government funded $2 million project was announced, and more The rail line was opened in two stages – to Dickabram on 1 than six years after the Theebine to Kingaroy railway line was January 1886 after completion of two crossings of the Mary River closed. and to Kilkivan on 6 December 1886. At the opening, South Burnett Mayor Keith Campbell told the Parliament approved an extension of the line south west to what audience the 88km long trail had two parts – the sealed South became Kingaroy on 12 December 1900. Burnett Rail Trail between Kingaroy and Murgon which was 43.5km long and only open to cyclists and pedestrians, but The extension was completed in three stages. not horses because it crossed the Tick Line, and the unsealed Kilkivan to Goomeri opened in August 1902 and had bridges 44.5km section between Murgon and Kilkivan which was open to across Wide Bay Creek and Kinbombi Creek. -

Visitor Information Bunya Mountains National Park

Visitor information National Park Bunya Mountains National Park Mountains Bunya was declared in 1908 and is Queensland's second oldest national park. For generations, people have gathered at the Bunya Mountains (Booburrgan Ngmmun) — where rainforest-clad peaks rising 500m above the plains shelter the world's largest stand of ancient bunya pines. Traditional Custodians from south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales gathered together for celebrations coinciding with heavy crops of bunya nuts. Today visitors picnic, camp, walk or relax in the cool climate of this isolated section of the Great Diving Range. Wildlife refuge Brilliantly coloured king parrots and crimson rosellas are sure to be seen on in the mountains your visit, as are red-necked wallabies With peaks reaching 1135m, moist feeding in grassy areas. Look carefully gullies and a variety of vegetation and you might also see satin bowerbirds, types, the Bunya Mountains has green catbirds and the huge tadpoles of sheltered and geographically isolated great barred-frogs. habitats in which a diversity of plants and animals thrive — including over Of the many animals that become active 30 rare and threatened species. at night, the Bunya Mountains ringtail possum is the only one you will not see Bunya pines Araucaria bidwillii anywhere else in the world. tower over tall moist rainforest along the range crest, while hoop pines Places to picnic and camp Araucaria cunninghamii dominate dry The park has three visitor areas — rainforest on lower slopes. Natural Dandabah, Westcott and Burton's Well. grassland "balds" containing rare All have toilets and picnic tables. Tracks across the mountains grass species are scattered across Enjoy weaving in and out of grasslands, the mountains. -

Key Reference Site 43: Coolabunia Research Site

Queensland Key Reference Sites Key Reference Site 43: Coolabunia Research Site Site details Site notes MGA Coordinates: 387113 mE 7056118 mN Zone 56 This reference site describes an upper slope posi- Lat/long: -26.53922 S 151.87243 E tion of the deeply weathered basalt landscapes of the South Burnett. Softwood scrub was Primary site: SALTE 744 cleared about 80 years ago (in the mid 1920s), 1 Geology: Tm - Main Range Volcanics and the land was used as pasture until crop- 2 Td/r - Tertiary ferricrete, red soils ping commenced in 1987. In this region, the Vegetation: Formerly softwood scrub. replacement of scrub and forest vegetation with Land use: Rainfed cultivation. First cropped mid crops and pasture has led to increased risk of 1990’s, after long term pasture. elevated groundwater and soil salinisation. This site has been used for research into the effects Site location of continuous cropping on soil properties and crop productivity5,6, for which it was regarded as permanent pasture site ‘paired’ with QKRS 40. This reference site consists of: • soil and regolith description to 6.4 m • measured electrical conductivity (EC), soluble chloride (Cl), extractable sulfur (SO4) and soil pH. • MIR laboratory analysis • measured bulk density5,6 • limited ‘wet’ chemistry including particle size analysis5,6 • soil moisture characteristics (and plant available water capacity)5,6 • aggregate stability5,6 • soil strength5,6 • infiltration5,6 QKRS 43 is therefore a key point of reference for understanding the soils formed on deeply weath- ered basalt in southern Queensland. Climate7 Compared to evaporation, a rainfall deficit is ex- Soil and landscape correlation perienced in every month of the year, and annual pan evaporation is 2.0 times the annual rain- Name Reference fall.