“The Human Condition” in Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot Michiko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Beckett's Peristaltic Modernism, 1932-1958 Adam

‘FIRST DIRTY, THEN MAKE CLEAN’: SAMUEL BECKETT’S PERISTALTIC MODERNISM, 1932-1958 ADAM MICHAEL WINSTANLEY PhD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE MARCH 2013 1 ABSTRACT Drawing together a number of different recent approaches to Samuel Beckett’s studies, this thesis examines the convulsive narrative trajectories of Beckett’s prose works from Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1931-2) to The Unnamable (1958) in relation to the disorganised muscular contractions of peristalsis. Peristalsis is understood here, however, not merely as a digestive process, as the ‘propulsive movement of the gastrointestinal tract and other tubular organs’, but as the ‘coordinated waves of contraction and relaxation of the circular muscle’ (OED). Accordingly, this thesis reconciles a number of recent approaches to Beckett studies by combining textual, phenomenological and cultural concerns with a detailed account of Beckett’s own familiarity with early twentieth-century medical and psychoanalytical discourses. It examines the extent to which these discourses find a parallel in his work’s corporeal conception of the linguistic and narrative process, where the convolutions, disavowals and disjunctions that function at the level of narrative and syntax are persistently equated with medical ailments, autonomous reflexes and bodily emissions. Tracing this interest to his early work, the first chapter focuses upon the masturbatory trope of ‘dehiscence’ in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, while the second examines cardiovascular complaints in Murphy (1935-6). The third chapter considers the role that linguistic constipation plays in Watt (1941-5), while the fourth chapter focuses upon peristalsis and rumination in Molloy (1947). The penultimate chapter examines the significance of epilepsy, dilation and parturition in the ‘throes’ that dominate Malone Dies (1954-5), whereas the final chapter evaluates the significance of contamination and respiration in The Unnamable (1957-8). -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

The Use of Internal and External “Fire and Heat Metaphors” in Some Rock Lyrics

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of English Do You Really Want to Set Me on Fire, My Love ? The Use of Internal and External “Fire and Heat Metaphors” in some Rock Lyrics Kalle Larsen Linguistic C-essay Spring 2006 Supervisor: Christina Alm-Arvius Abstract The aim of this study has been to investigate whether metaphors in terms of fire and heat in rock lyrics can be interpreted figuratively as well as literally. The terms for these latter two categories are internal and external metaphors . Many rock lyrics are about love, a theme often described with the use of metaphors. One common type of metaphorisation for describing love is to use what in this study has been called “fire and heat metaphors”. These are metaphors that as their source use FIRE and HEAT/WARMTH and map some of these qualities on to the metaphorical target LOVE, which results in metaphorical constructions like I am on fire . Internal and external metaphors are terms coined by Alm-Arvius (2003:78) and they serve the purpose of separating the metaphors that cannot be taken literally from those that can also be given a literal meaning in another context. The main aim of this study has been to investigate whether a set of chosen metaphorical constructions taken from different rock songs can also be interpreted literally in relation to another universe of discourse. Moreover, the semantic and syntactic structures of the metaphor examples have been outlined, and some theories why the constructions should be regarded as internal or external metaphors have been presented. A number of related underlying cognitive structures ( conceptual metaphors ) were identified in this study, and (BEING IN) LOVE IS (EXPERIENCING) HEAT/WARMTH is a structure that allows external metaphorical constructions. -

Trauma, Company and Witnessing in Samuel Beckett's Post-War Drama

TRAUMA, COMPANY AND WITNESSING IN SAMUEL BECKETT’S POST-WAR DRAMA, 1952-61 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 ELECTRA GEORGIADES SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES 2 LIST OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Declaration 4 Copyright Statement 5 Acknowledgements 6 1. Introduction 7 1.1. Beckett and Trauma: The Theoretical Framework 12 1.2. Performing Testimony 25 1.3. Human Company: The Other as a Witness 36 1.4. Thesis Structure 41 2. In Need of a Witness: Beckett’s Testimonial Drama (1952-61) 45 2.1. Trauma, Testimony and the Theatre 48 2.2. Beside History: Beckett’s Testimonial Drama 66 2.2.1 Performing Trauma 69 2.2.2 Performing and Responding to Testimony 86 3. Acting out the Trauma: Memory, Language and the Body 99 3.1. Memory 109 3.2. Language 133 3.3. The Body 142 4. Reclaiming Witnessing in the Post-war Period: Human Company in Beckett’s Drama Trilogy 158 4.1. Human Company and Trauma 161 4.2. Resisting the Trauma: Company and Witnessing 189 5. Conclusion: Trauma, Company and Witnessing in Samuel Beckett’s Post-war Drama 205 5.1. Beckett and Trauma 208 5.2. The Human Other 212 Bibliography 217 Primary Sources 217 Secondary Sources 218 Words: 80,551 3 ABSTRACT The present thesis examines the interrelation between the dynamics of human company and the psychoanalytic concept of witnessing in Samuel Beckett’s major post-war drama. The analysis provided concentrates primarily on Waiting for Godot (1952), Endgame (1957), and Happy Days (1962) and situates these plays within a post-war framework, while examining their stylistic qualities and thematic concerns within the context of trauma studies. -

BAM Announces the Complete Cast of Beckett's Endgame, Featuring John Turturro and Directed by Andrei Belgrader Running April

BAM announces the complete cast of Beckett’s Endgame, featuring John Turturro and directed by Andrei Belgrader running April 25–May 18 Max Casella, Elaine Stritch, and Alvin Epstein to join cast BAM 2008 Spring Season is sponsored by Bloomberg Endgame Written by Samuel Beckett Directed by Andrei Belgrader Produced by BAM BAM Harvey Theater (651 Fulton St.) April 25 & 26 at 7:30 Apr 29—May 3, May 6—10, May 13—17 at 7:30pm (note: Apr 30 is the press opening) May 3, 10 & 17 at 2pm April 27, May 4, 11 & 18 at 3pm Tickets: $25, 45, 65, 75 BAM.org or 718.636.4100 Brooklyn, NY/March 11, 2008—BAM announces the complete cast of its upcoming production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame. Joining John Turturro (Hamm) will be acclaimed TV, stage, and screen actor Max Casella (“The Sopranos,” The Lion King) as Clov. Veteran classical actor Alvin Epstein (Waiting for Godot, The Three Penny Opera, Tuesdays with Morrie) will play Nagg and the legendary Broadway actress Elaine Stritch will play Nell. The one-act play, originally published in 1957, is considered to be one of Beckett’s most important works. Endgame will be directed by Andrei Belgrader (American Repertory Theatre’s Ubu Rock, Yale Repertory Theatre’s Scapin). Twenty-four performances of Endgame will take place in the BAM Harvey Theater (651 Fulton St.) from April 25 through May 18 (press opening: April 30). Tickets, priced at $25, 45, 65, 75, can be purchased by calling BAM Ticket Services at 718.636.4100 or by visiting BAM.org. -

Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable

83 Rhythms in Rockaby: Ways of Approaching the Unknowable. Leonard H. Knight Describing Samuel Beckett's later, and progressively shorter, pieces in a word is peculiarly difficult. The length of the average critical commentary on them testifies to this, and is due largely to an unravelling of compression in the interests of meaning: straightening out a tightly C9iled spring in order to see how it is made. The analogy, while no more exact than any analogy, is useful at least in suggesting two things: the difficulty of the endeavour; and the feeling, while engaged in it, that it may be largely counterproductive. A straightened out spring, after all, is no longer a spring. Aware of the pitfalls I should nevertheless like, in this paper, to look at part of the mechanism while trying to keep its overall shape relatively intact. The ideas in a Beckett play emerge, in general, from an initial image. A woman half-buried in a grass mound. A faintly spotlit, endlessly talking mouth. Feet tracing a fixed, unvarying path. Concrete and intensely theatrical, the image is immediately graspable. Its force and effectiveness come, above all, from its simpl icity. Described in this way Beckett's images sound arresting to the point of sen sationalism. What effectively lowers the temperature while keeping the excitement generated by their o.riginality is the simple fact that they cannot easily be made out. They are seen, certainly - but only just. In the dimmest possible light; the absolute minimum commensurate with sight. What is initially seen is only then augmented or reinforced by what is said. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRApHY PUBLISHED WORKS BY SAMUEL BECKETT Beckett, Samuel. “Dante… Bruno. Vico.. Joyce.” In Poems, Short Fiction, Criticism. Vol. 4 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 495–510. New York: Grove, 2006. ———. Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment. Edited by Ruby Cohn. London: Calder, 1983. ———. Eleutheria. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1995. ———. Eleutheria. Translated by Barbara Wright. London: Faber, 1996. ———. Fin de Partie. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1957. ———. “First Love.” In Poems, Short Fiction, Criticism. Vol. 4 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 229–246. ———. Ill Seen Ill Said. In Poems, Short Fiction, Criticism. Vol. 4 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 451–470. ———. “La Fin.” In Nouvelles et Textes pour rien, 77–123. ———. L’Innommable. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2004. ———. Malone Dies. In Novels II. Vol. 2 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 171–281. ———. Malone Meurt. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2004. ———. Mal vu mal dit. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1981. ———. Mercier and Camier. In Novels I. Vol. 1 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 381–479. ———. Mercier et Camier. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1970. ———. Molloy. In Novels II. Vol. 2 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 1–170. ———. Molloy. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1982. ———. Murphy. In Novels I. Vol. 1 of The Grove Centenary Edition, 1–168. ———. Murphy. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1965. © The Author(s) 2018 213 T. Lawrence, Samuel Beckett’s Critical Aesthetics, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75399-7 214 BIBLIOGRAPHY ———. Nouvelles et Textes pour rien, avec 6 illustrations d’Avigdor Arikha. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1958. ———. Pour finir encore et autres foirades. -

Travels with Samuel Beckett, 1928-1946

Beyond the Cartesian Pale: Travels with Samuel Beckett, 1928-1946 Charles Travis [I]t is the act and not the object of perception that matters. Samuel Beckett, “Recent Irish Poetry,” e Bookman (1934).1 Introduction he Irish Nobel laureate Samuel Beckett’s (1902-1989) early writings of the 1930s and 1940s depict the cities of Dublin, London and Saint-Lô Tin post-war France, with affective, comedic and existential flourishes, respectively. These early works, besides reflecting the experience of Beckett’s travels through interwar Europe, illustrate a shift in his literary perspective from a latent Cartesian verisimilitude to a more phenomenological, frag- mented and dissolute impression of place. This evolution in Beckett’s writing style exemplifies a wider transformation in perception and thought rooted in epistemological, cultural and philosophical trends associated with the Conti- nental avant garde emerging in the wake of the fin de siècle. As Henri Lefeb- vre has noted: Around 1910, the main reference systems of social practice in Eu- rope disintegrated and even collapsed. What had seemed estab- lished for good during the belle époque of the bourgeoisie came to an end: in particular, space and time, their representation and real- ity indissociably linked. In scientific knowledge, the old Euclidian and Newtonian space gave way to Einsteinian relativity. But at the same time, as is evident from the painting of the period—Cézanne first of all, then analytical Cubism—perceptible space and per- spective disintegrated. The line of horizon, optical meeting-point of parallel lines, disappeared from paintings.2 At the age of fourteen, Beckett, a son of the Protestant Anglo Irish bourgeoisie, witnessed in the largely Catholic nationalist uprising in Ireland, something Charles Travis is at Trinity College Dublin, Long Room Hub. -

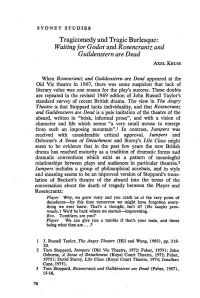

Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Axel KRUSI;

SYDNEY STUDIES Tragicomedy and Tragic Burlesque: Waiting for Godot and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead AxEL KRUSI; When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead appeared at the .Old Vic theatre' in 1967, there was some suspicion that lack of literary value was one reason for the play's success. These doubts are repeated in the revised 1969 edition of John Russell Taylor's standard survey of recent British drama. The view in The Angry Theatre is that Stoppard lacks individuality, and that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is a pale imitation of the theatre of the absurd, wrillen in "brisk, informal prose", and with a vision of character and life which seems "a very small mouse to emerge from such an imposing mountain".l In contrast, Jumpers was received with considerable critical approval. Jumpers and Osborne's A Sense of Detachment and Storey's Life Class might seem to be evidence that in the past few years the new British drama has reached maturity as a tradition of dramatic forms aitd dramatic conventions which exist as a pattern of meaningful relationships between plays and audiences in particular theatres.2 Jumpers includes a group of philosophical acrobats, and in style and meaning seems to be an improved version of Stoppard's trans· lation of Beckett's theatre of the absurd into the terms of the conversation about the death of tragedy between the Player and Rosencrantz: Player Why, we grow rusty and you catch us at the very point of decadence-by this time tomorrow we might have forgotten every thing we ever knew. -

Beckett in Black and Red: the Translations for Nancy Cunard's Negro

University of Kentucky UKnowledge French and Francophone Literature European Languages and Literatures 2000 Beckett in Black and Red: The Translations for Nancy Cunard's Negro Alan Warren Friedman University of Texas Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Friedman, Alan Warren, "Beckett in Black and Red: The Translations for Nancy Cunard's Negro" (2000). French and Francophone Literature. 10. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_french_and_francophone_literature/10 IRISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, AND CULTURE Jonathan Allison, General Editor Advisory Board George Bornstein, University of Michigan Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, University of Texas James S. Donnelly Jr., University ofWisconsin Marianne Elliott, University of Liverpool Roy Foster, Hertford College, Oxford David Lloyd, Scripps College Weldon Thornton, University of North Carolina This page intentionally left blank BECI<ETT . In BLACIZ and The Translations for RED Nancy Cunard's NEGRO (1934) EDITED BY ALAN WARREN FRIEDMAN THE UNIVERSrrY PRESS OF KENIUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2000 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

Disjecta Membra a Poetic Interplay of Fragments

disjecta membra disjecta membra A poetic interplay of fragments Lyna Ayr master of art & design 2012 contents page. attestation of authorship [011] intellectual property rights [013] acknowledgements [015] abstract [017] synopsis [019] introduction [021] chapter 1: positioning of the researcher [023] Illustrating poetics [024] Childhood and the fragment [035] Culture and fracture [036] John the Baptist [037] chapter 2: review of contextual knowledge [039] Disjecta Membra as a poetic concept [040] Constructions of the death of John the Baptist [041] Poetry-film as a media form [043] chapter 3: methodology [047] Heuristics [049] Design of the research [050] Reviewing and pattern finding [051] Breaking [052] Making and order [061] Reassembly and refinement [071] chapter 4: critical commentary [077] This exegesis is submitted to the Auckland University of Technology Poetry-film [078] for the Masters of Art & Design. Disjecta membra and textual fragments [080] Lyna Ayr B. Art & Design Honours, AUT University: Auckland. 2011 Lyna Ayr, B. Graphic Design, AUT University: Auckland. 2009 Iconography [082] Printed July 2013 Structure [088] © Lyna Ayr 2014 All rights reserved. conclusion This publication, may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, The work and its journey [090] mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the Post examination reflective statement [092] prior permission of the owner. Printed and bound by Printsprint, Wellesley, Auckland. 5 table of images chapter 1 [positioning of researcher] reference list [095] Creative texts relating to the beheading of John the Baptist [100] Figure 1:1 Ayr, L. (2009) Mother the Eternal [Photography, 376 mm x 1200mm]. -

The Work of Poverty

THE WORK OF POVERTY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • The Work of Poverty SAMUEL BECKEtt’S VAGABONDS AND THE THEATER OF CRISIS Lance Duerfahrd THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2013 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Duerfahrd, Lance Alfred, 1967– The work of poverty : Samuel Beckett's vagabonds and the theater of crisis / Lance Duerfahrd. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1237-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1237-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9339-3 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9339-5 (cd-rom) 1. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989. En attendant Godot. English—Criticism and interpreta- tion. 2. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Influence. I. Title. PQ2603.E378Z618 2013 842'.914—dc23 2013022653 Cover design by Jennifery Shoffey-Forsythe Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents • • • • • • • • • • • List of Illustrations vi Acknowledgments vii INTRODUCTION Begging Context 1 CHAPTER 1 Godot behind Bars 12 CHAPTER 2 Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo and New Orleans 63 CHAPTER 3 La Pensée Vagabonde: Vagabond Thought 112 CHAPTER 4 Textual Indigence: The Reader in an Aesthetics of Poverty 143 AFTERWORD Staging Godot in