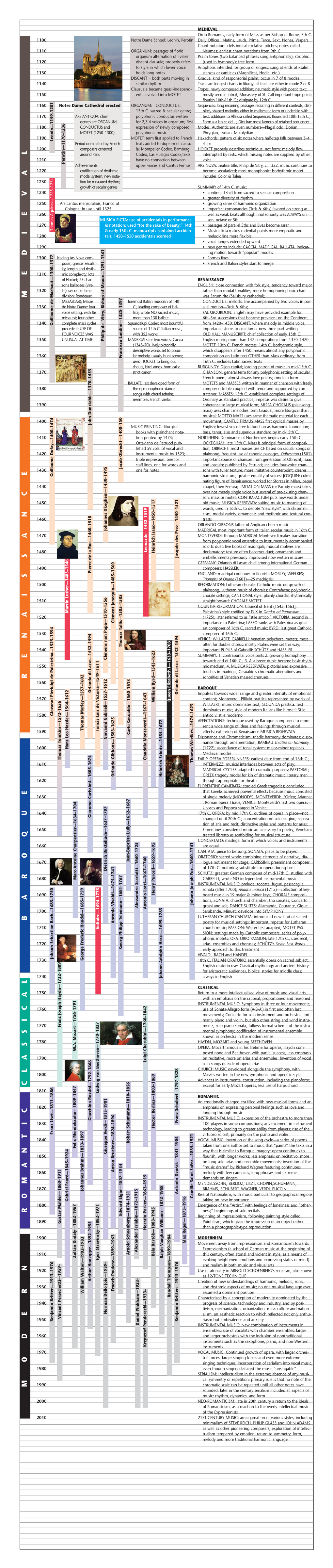

Music History Timeline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Johann Sebastian Bach's St. John Passion from 1725: a Liturgical Interpretation

Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion from 1725: A Liturgical Interpretation MARKUS RATHEY When we listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s vocal works today, we do this most of the time in a concert. Bach’s passions and his B minor Mass, his cantatas and songs are an integral part of our canon of concert music. Nothing can be said against this practice. The passions and the Mass have been a part of the Western concert repertoire since the 1830s, and there may not have been a “Bach Revival” in the nineteenth century (and no editions of Bach’s works for that matter) without Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s concert performance of the St. Matthew Passion in the Berlin Singakademie in 1829.1 However, the original sitz im leben of both large-scaled works like his passions, and his smaller cantatas, is the liturgy. Most of his vocal works were composed for use during services in the churches of Leipzig. The pieces unfold their meaning in the context of the liturgy. They engage in a complex intertextual relationship with the liturgical texts that frame them, and with the musical (and theological) practices of the liturgical year of which they are a part. The following essay will outline the liturgical context of the second version of the St. John Passion (BWV 245a) Bach performed on Good Friday 1725 in Leipzig. The piece is a revision of the familiar version of the passion Bach had composed the previous year. The 1725 version of the passion was performed by the Yale Schola Cantorum in 2006, and was accompanied by several lectures I gave in New Haven and New York City. -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

4970379-70Ef42-714439855734.Pdf

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT la messe nostre-dame - l ‘ amour courtois ARS ANTIQUA DE PARIS directed by michel sanvoisin Joseph Sage, countertenor Hugues Primard, tenor Pierre Eyssartier, tenor Marc Guillard, baritone Michel Sanvoisin, recorders Philippe Matharel, cornet Raymond Cousté, lute Colette Lequien, vièle Marie Jeanne Serero, organ La Messe Nostre-Dame 1. Kyrie I, Christe, Kyrie II, Kyrie III 06:52 2. Gloria 05:12 3. Credo 06:44 4. Sanctus 04:35 5. Agnus Dei 03:29 6. Gratias 01:44 L'Amour Courtois 7. De Toutes Flours (organ, vièle) 03:31 8. Quant Theseus (two tenors, vièle, organ, lute) 04:44 9. Plus Dure Que Un Dyamant (lute) 01:59 10. Ma Fin Est Mon Commencement (countertenor, recorder, lute) 06:14 11. Hoquet David (vièle, organ, lute) 02:16 12. Douce Dame Jolie (countertenor) 03:54 13. Ce Qui Soutient Moy (recorder, lute) 01:29 14. Rose, Liz (tenor, baritone, organ, vièle, cornet, lute) 04:16 15. Dame, Ne Regardes Pas (recorder, vièle) 01:51 16. Ma Chiere Dame (countertenor, recorder, vièle, lute) 01:46 17. Dame, Se Vous M'estes Lonteinne (baritone, organ, vièle, cornet) 02:55 18. Trop Plus Est Belle (vocal and intstrumental ensemble) 02:59 TOTAL PLAYING TIME 68:14 Recorded at Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, Venice 1990 Recording Engineers: Silvia and Giovanni Melloncelli p©20161Edelweiss Emission The Originals is a unique series that has once again been made available for audiophiles, so they can enjoy the stellar euphonic sound of EDELWEISS EMISSION. 2016 begins with the reissue of a previously sold out series of outstanding releases performed by a number of celebrated musicians. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

San Francisco Early Music Society

San Francisco Early Music Society Breathtaking: A Cornetto and a Voice Entwined WHEN: VENUE: Sunday, May 6, 2018 BInG 4:00 PM COnCERT HaLL Program Artists Maurizio Cazzati (1616 –1678) Hana Blažíková, Regina coeli soprano Bruce dickey, Nicolò Corradini (?–1646) cornetto Spargite flores Tekla Cunningham, Biagio Marini (1594 –1663) Ingrid Matthews, Sonata seconda a doi violini violin Joanna Blendulf, Sigismondo D’India (c1582 –1629) viola da gamba Dilectus meus Langue al vostro languir Michael Sponseller, organ and harpsichord Giovanni Battista Fontana (1589–1630) Stephen Stubbs, Sonata 11 a 2 theorbo and baroque guitar Tarquinio Merula (c 1594–1665) Nigra sum Giacomo Carissimi (1605 –1674) Summi regis puerpera —Intermission— Calliope Tsoupaki (b. 1963) Mélena imí (Nigra sum) , 2015 Gio. Battista Bassani (c1650 –1716) Three arias from La Morte Delusa (Ferrara, 1680) “Sinfonia avanti l’Oratorio” “Speranza lusinghiera” “Error senza dolor” Sonata prima a 3, Op. 5 Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725 Three arias from Emireno (Naples, 1697) Rosinda: “non pianger solo dolce usignuolo” Rosinda: “Senti, senti ch’io moro” Emireno: “Labbra gradite” PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE . Please be considerate of others and turn off all phones, pagers, and watch alarms. Photography and recording of any kind are not permitted. Thank you. 2 Notes Breathtaking: violoncelli. He was able, however, to which included innovative composers A Voice And A Cornetto Entwined attract excellent singers as well as such as Giovanni de Macque. d’India string players to the basilica. His travelled extensively, holding positions In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Regina coeli , from a collection of in Turin, Modena and Rome. His cornetto was fabled for its remarkable Marian antiphons published in 1667, monodies, for which he is primarily ability to imitate the human voice. -

PÉROTIN and the ARS ANTIQUA the Hilliard Ensemble

CORO hilliard live CORO hilliard live 1 The Hilliard Ensemble For more than three decades now The Hilliard Ensemble has been active in the realms of both early and contemporary music. As well as recording and performing music by composers such as Pérotin, Dufay, Josquin and Bach the ensemble has been involved in the creation of a large number of new works. James PÉROTIN MacMillan, Heinz Holliger, Arvo Pärt, Steven Hartke and many other composers have written both large and the and small-scale pieces for them. The ensemble’s performances ARS frequently include collaborations with other musicians such as the saxophonist Jan Garbarek, violinist ANTIQUA Christoph Poppen, violist Kim Kashkashian and orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra. John Potter’s contribution was crucial to getting the Hilliard Live project under way. John has since left to take up a post in the Music Department of York University. His place in the group has been filled by Steven Harrold. www.hilliardensemble.demon.co.uk the hilliard ensemble To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs, visit www.thesixteen.com cor16046 The hilliard live series of recordings came about for various reasons. 1 Vetus abit littera Anon. (C13th) 3:47 At the time self-published recordings were a fairly new and increasingly David James Rogers Covey-Crump John Potter Gordon Jones common phenomenon in popular music and we were keen to see if 2 Deus misertus hominis Anon. (C13th) 5:00 we could make the process work for us in the context of a series of David James Rogers Covey-Crump John Potter Gordon Jones public concerts. -

The Neumeister Collection of Chorale Preludes of the Bach Circle: an Examination of the Chorale Preludes of J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 "The eumeiN ster collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works Sara Ann Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Sara Ann, ""The eN umeister collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 77. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/77 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NEUMEISTER COLLECTION OF CHORALE PRELUDES OF THE BACH CIRCLE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHORALE PRELUDES OF J. S. BACH AND THEIR USAGE AS SERVICE MUSIC AND PEDAGOGICAL WORKS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts Sara Ann Jones B. A., McNeese State University -

B Ach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner

Bach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner 1 Bach Cantatas for Christmas Gardiner 2 The Bach Cantata Pilgrimage On Christmas Day 1999 a unique celebration of the new Millennium began in the Herderkirche in Weimar, Germany: the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists under the direction of Sir John Eliot Gardiner set out to perform all Johann Sebastian Bach’s surviving church cantatas in the course of the year 2000, the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. The cantatas were performed on the liturgical feasts for which they were composed, in a year-long musical pilgrimage encompassing some of the most beautiful churches throughout Europe (including many where Bach himself performed) and culminating in three concerts in New York over the Christmas festivities at the end of the millennial year. These recordings of cantatas for the Christmas season were made at the beginning and end of the Pilgrimage. 3 Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas for Christmas and New Year Pages 5-13 CD 1 For Christmas Day 63 / 191 14-24 CD 2 For Christmas Day 91 / 110 For the Second Day of Christmas 121 / 40 25-38 CD 3 For the Second Day of Christmas 57 For the Third Day of Christmas 64 / 151 / 133 39-50 CD 4 For the Sunday after Christmas Motet 225 / 152 / 122 / 28 For New Year’s Day 190 51-62 CD 5 For New Year’s Day 143 / 41 / 16 / 171 63-73 CD 6 For the Sunday after New Year 153 / 58 For Epiphany 65 / 123 The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Weimar / New York / Berlin / Leipzig 1999-2000 4 For Christmas Day Claron McFadden soprano Bernarda Fink alto Christoph Genz tenor Dietrich Henschel bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists 1 John Eliot Gardiner Herderkirche, Weimar, 25 December 1999 « Contents page 5 CD1 40:15 For Christmas Day 26:28 Christen, ätzet diesen Tag BWV 63 1 (4:48) 1. -

Stile Antico Josquin

Boston Early Music Festival in partnership with The Morgan Library & Museum present Stile Antico Josquin: Father of the Renaissance Ave Maria…virgo serena Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450–1521) Kyrie from Missa Pange lingua Josquin Vivrai je tousjours Josquin El grillo Josquin Inviolata, integra et casta es Maria Josquin Gloria from Missa Pange lingua Josquin Mille regretz Josquin Salve regina a5 Josquin O mors inevitabilis Hieronymus Vinders (fl. ca. 1525) Agnus Dei I and III from Missa Pange lingua Josquin Dum vastos Adriae fluctus Jacquet de Mantua (1483–1559) Friday, February 26, 2021 at 8pm Livestream broadcast Filmed concert from All Saints Church, West Dulwich, London, England BEMF.org Stile Antico Helen Ashby, Kate Ashby, Rebecca Hickey, soprano Emma Ashby, Cara Curran, Eleanor Harries, alto Andrew Griffiths, Jonathan Hanley, Benedict Hymas, tenor James Arthur, Will Dawes, Nathan Harrison, bass This concert is organized with the cooperation of Knudsen Productions, LLC, exclusive North American artist representative of Stile Antico. Stile Antico records for Decca. PROGRAM NOTES Our program tonight is devoted to the wonderful music of Josquin des Prez, marking 500 years since his death in 1521. Josquin was unquestionably a star in his own time: no lesser figure than Martin Luther praised him as “the master of the notes,” while for the theorist Glarean, “no one has more effectively expressed the passions of the soul in music…his talent is beyond description.” So what is it about Josquin that exerted such a spell on the generations that followed—and which still speaks so eloquently to us today? Much about Josquin’s biography and career remains shadowy: it isn’t always possible to pin down where he was working, and—with a few exceptions—the chronology of his works can only be attempted on stylistic grounds. -

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in JS Bach's Organ Fugues

A Study of Musical Rhetoric in J. S. Bach’s Organ Fugues BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao BFA, National Taiwan Normal University, 1999 MA, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2002 MEd, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2003 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA Abstract This study explores the musical-rhetorical tradition in German Baroque music and its connection with Johann Sebastian Bach’s fugal writing. Fugal theory according to musica poetica sources includes both contrapuntal devices and structural principles. Johann Mattheson’s dispositio model for organizing instrumental music provides an approach to comprehending the process of Baroque composition. His view on the construction of a subject also offers a way to observe a subject’s transformation in the fugal process. While fugal writing was considered the essential compositional technique for developing musical ideas in the Baroque era, a successful musical-rhetorical dispositio can shape the fugue from a simple subject into a convincing and coherent work. The analyses of the four selected fugues in this study, BWV 546, 552.2, 577, and 582, will provide a reading of the musical-rhetorical dispositio for an understanding of Bach’s fugal writing. ii Copyright © 2015 by Wei-Chun Liao All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements The completion of this document would not have been possible without the help and support of many people.