Grace Crowley's Contribution to Australian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emu Island: Modernism in Place

Emu Island: Modernism in Place Visual Arts Syllabus Stages 5 - 6 CONTENTS 3 Introduction to Emu Island: Modernism in Place 4 Introduction to education resource Syllabus Links Conceptual framework: Modernism 6 Modernism in Sydney 7 Gerald and Margo Lewers: The Biography 10 Timeline 11 Mud Map Case study – Sydney Modernism Art and Architecture Focus Artists 13 Tony Tuckson 14 Carl Plate 16 Frank Hinder 18 Desiderius Orban 20 Modernist Architecture 21 Ancher House 23 Young Moderns 24 References 25 Bibliography Front Page Margel Hinder Frank Hinder Currawongs Untitled c1946 1945 shale and aluminium collage and gouache on paper 25.2 x 27 x 11 24 x 29 Gift of Tanya Crothers and Darani Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers, 1980 Lewers Bequest Collection Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Margel Hinder Emu Island: Modernism in Place Emu Island: Modernism in Place celebrates 75 years of Modernist art and living. Once the home and studio of artist Margo and Gerald Lewers, the gallery site, was, as it is today - a place of lively debate, artistic creation and exhibitions at the foot of the Blue Mountains. The gallery is located on River Road beside the banks of the Nepean River. Once called Emu Island, Emu Plains was considered to be the land’s end, but as the home of artist Margo and Gerald Lewers it became the place for new beginnings. Creating a home founded on the principles of modernism, the Lewers lived, worked and entertained like-minded contemporaries set on fostering modernism as a holistic way of living. -

DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION from PICTURES to OBJECTS Monica Amor

REVIEW ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/3/2/101/720214/artm_r_00083.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION FROM PICTURES TO OBJECTS monica amor suárez, osbel. cold america: geometric abstraction in latin america (1934–1973). exhibition presented by the Fundación Juan march, madrid, Feb 11–may 15, 2011. crispiani, alejandro. Objetos para transformar el mundo: Trayectorias del arte concreto-invención, Argentina y Chile, 1940–1970 [Objects to Transform the World: Trajectories of Concrete-Invention Art, Argentina and Chile, 1940–1970]. buenos aires: universidad nacional de Quilmes, 2011. The literature on what is generally called Latin American Geometric Abstraction has grown so rapidly in the past few years, there is no doubt that the moment calls for some refl ection. The fi eld has been enriched by publications devoted to Geometric Abstraction in Uruguay (mainly on Joaquín Torres García and his School of the South), Argentina (Concrete Invention Association of Art and Madí), Brazil (Concretism and Neoconcretism), and Venezuela (Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art). The bulk of the writing on these movements, and on a cadre of well-established artists, has been published in exhibition catalogs and not in academic monographs, marking the coincidence of this trend with the consolidation of major private collections and the steady increase in auction house prices. Indeed, exhibitions of what we can broadly term Latin American © 2014 ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Annual Report 2012 – 13

ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL REPORT 2012 – 13 1 CONTENTS 4 Vision and strategic direction 2010 – 15 5 President’s foreword 9 Director’s statement 13 At a glance 15 Access 15 Exhibitions and audience programs 19 Future exhibitions 21 Publishing 23 Engaging 23 Digital engagement 23 Community 30 Education 35 Outreach Regional NSW 40 Stewarding 40 Building and environmental management 42 Corporate Governance 58 Collecting 58 Major collection acquisitions 67 Other collection activity 70 Appendices 123 General Access Information 131 Financial statements 2 ART GALLERY OF NSW ANNUAL REPORT 12-13 The Hon George Souris MP Minister for Tourism, Major Events, Hospitality and Racing, and Minister for the Arts Parliament House Macquarie Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister It is our pleasure to forward to you for presentation to the NSW Parliament the annual report for the Art Gallery of NSW for the year ended 30 June 2013. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions of the Annual Report (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Regulations 2010. Yours sincerely Steven Lowy Michael Brand President Director Art Gallery of NSW Trust 21 October 2013 3 VISION AND STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2010 – 2015 Vision The Gallery is dedicated to serving the widest possible audience, both nationally and internationally, as a centre of excellence for the collection, preservation, documentation, . interpretation and display of Australian and international art. The Gallery is also dedicated to providing a forum for scholarship, art education and the exchange of ideas. Strategic Directions Access To continue to improve access to our collection, resources and expertise through exhibitions, publishing, programs, new technologies and partnerships. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017

PenrithIan Milliss: Regional Gallery & Modernism in Sydney and InternationalThe Lewers Trends Bequest Emu Island: Modernism in Place 26 August — 19 November 2017 Emu Island: Modernism in Place Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 1 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction 75 Years. A celebration of life, art and exhibition This year Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest celebrates 75 years of art practice and exhibition on this site. In 1942, Gerald Lewers purchased this property to use as an occasional residence while working nearby as manager of quarrying company Farley and Lewers. A decade later, the property became the family home of Gerald and Margo Lewers and their two daughters, Darani and Tanya. It was here the family pursued their individual practices as artists and welcomed many Sydney artists, architects, writers and intellectuals. At this site in Western Sydney, modernist thinking and art practice was nurtured and flourished. Upon the passing of Margo Lewers in 1978, the daughters of Margo and Gerald Lewers sought to honour their mother’s wish that the house and garden at Emu Plains be gifted to the people of Penrith along with artworks which today form the basis of the Gallery’s collection. Received by Penrith City Council in 1980, the Neville Wran led state government supported the gift with additional funds to create a purpose built gallery on site. Opened in 1981, the gallery supports a seasonal exhibition, education and public program. Please see our website for details penrithregionalgallery.org Cover: Frank Hinder Untitled c1945 pencil on paper 24.5 x 17.2 Gift of Frank Hinder, 1983 Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest Collection Copyright courtesy of the Estate of Frank Hinder Penrith Regional Gallery & The Lewers Bequest 2 Spring Exhibition Suite 26 August — 19 November 2017 Introduction Welcome to Penrith Regional Gallery & The of ten early career artists displays the on-going Lewers Bequest Spring Exhibition Program. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Making 18 01–20 05

artonview art o n v i ew ISSUE No.49 I ssue A U n T U o.49 autumn 2007 M N 2007 N AT ION A L G A LLERY OF LLERY A US T R A LI A The 6th Australian print The story of Australian symposium printmaking 18 01–20 05 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra John Lewin Spotted grossbeak 1803–05 from Birds of New South Wales 1813 (detail) hand-coloured etching National Gallery of Australia, Canberra nga.gov.au InternatIonal GallerIes • australIan prIntmakInG • modern poster 29 June – 16 September 2007 23 December 2006 – 6 May 2007 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra National Gallery of Australia, Canberra George Lambert The white glove 1921 (detail) Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney purchased 1922 photograph: Jenni Carter for AGNSW Grace Crowley Painting 1951 oil on composition board National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 1969 nga.gov.au nga.gov.au artonview contents 2 Director’s foreword Publisher National Gallery of Australia nga.gov.au 5 Development office Editor Jeanie Watson 6 Masterpieces for the Nation appeal 2007 Designer MA@D Communication 8 International Galleries Photography 14 The story of Australian printmaking 1801–2005 Eleni Kypridis Barry Le Lievre Brenton McGeachie 24 Conservation: print soup Steve Nebauer John Tassie 28 Birth of the modern poster Designed and produced in Australia by the National Gallery of Australia 34 George Lambert retrospective: heroes and icons Printed in Australia by Pirion Printers, Canberra 37 Travelling exhibitions artonview ISSN 1323-4552 38 New acquisitions Published quarterly: Issue no. 49, Autumn 2007 © National Gallery of Australia 50 Children’s gallery: Tools and techniques of printmaking Print Post Approved 53 Sculpture Garden Sunday pp255003/00078 All rights reserved. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

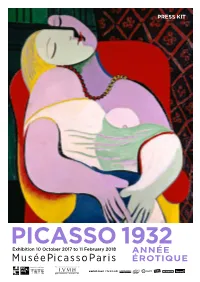

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Ii: Mary Alice Evatt, Modern Art and the National Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cultivating the Arts Page 394 CHAPTER 9 - WAGING WAR ON THE ESTABLISHMENT? II: MARY ALICE EVATT, MODERN ART AND THE NATIONAL ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES The basic details concerning Mary Alice Evatt's patronage of modern art have been documented. While she was the first woman appointed as a member of the board of trustees of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, the rest of her story does not immediately suggest continuity between her cultural interests and those of women who displayed neither modernist nor radical inclinations; who, for example, manned charity- style committees in the name of music or the theatre. The wife of the prominent judge and Labor politician, Bert Evatt, Mary Alice studied at the modernist Sydney Crowley-Fizelle and Melbourne Bell-Shore schools during the 1930s. Later, she studied in Paris under Andre Lhote. Her husband shared her interest in art, particularly modern art, and opened the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne 1939, and an exhibition in Sydney in the same year. His brother, Clive Evatt, as the New South Wales Minister for Education, appointed Mary Alice to the Board of Trustees in 1943. As a trustee she played a role in the selection of Dobell's portrait of Joshua Smith for the 1943 Archibald Prize. Two stories thus merge to obscure further analysis of Mary Alice Evatt's contribution to the artistic life of the two cities: the artistic confrontation between modernist and anti- modernist forces; and the political career of her husband, particularly knowledge of his later role as leader of the Labor opposition to Robert Menzies' Liberal Party. -

Art Gallery of New South Wales 2017: Our Year in Review

Art Wales South Gallery New of ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 201 7 2017 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 2017 2 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2017 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2017 3 Our year in review 4 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2017 6 OUR VISION 7 FROM THE PRESIDENT David Gonski 8 FROM THE DIRECTOR Michael Brand 10 2017 AT A GLANCE 12 SYDNEY MODERN PROJECT 16 ART 42 IDEAS 50 AUDIENCE 62 PARTNERS 78 PEOPLE 86 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 88 EXECUTIVE 89 CONTACTS 90 2018 PREVIEW The Gadigal people of the Eora nation are the traditional custodians of the land on which the Art Gallery of New South Wales stands. We respectfully acknowledge their Elders past, present and future. Our vision From its base in Sydney, the Art Gallery of New South Wales is dedicated to serving the widest possible audience as a centre of excellence for the collection, preservation, documentation, interpretation and display of Australian and international art, and a forum for scholarship, art education and the exchange of ideas. page 4: A view from the Grand Courts to the entrance court showing Bertram Mackennal’s Diana wounded 1907–08 and Emily Floyd’s Kesh alphabet 2017. 6 Art Gallery of New South Wales 2017 DAVID GONSKI AC PRESIDENT ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES TRUST and the Hon Adam Marshall MP, Glenfiddich, Herbert Smith Freehills, Minister for Tourism and Major Events. JCDecaux, J.P. Morgan, Macquarie Group, Macquarie University, The funding collaboration between McWilliam’s Wines & Champagne government and philanthropists for Taittinger, Paspaley Pearls, Sofitel our expansion will be the largest in FROM Sydney Wentworth, the Sydney the history of Australian arts.