Charles M. Russell's Historical Perspective in His Published Stories and Essays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

American Heritage Day

American Heritage Day DEAR PARENTS, Each year the elementary school students at Valley Christian Academy prepare a speech depicting the life of a great American man or woman. The speech is written in the first person and should include the character’s birth, death, and major accomplishments. Parents should feel free to help their children write these speeches. A good way to write the speech is to find a child’s biography and follow the story line as you construct the speech. This will make for a more interesting speech rather than a mere recitation of facts from the encyclopedia. Students will be awarded extra points for including spiritual application in their speeches. Please adhere to the following time limits. K-1 Speeches must be 1-3 minutes in length with a minimum of 175 words. 2-3 Speeches must be 2-5 minutes in length with a minimum of 350 words. 4-6 Speeches must be 3-10 minutes in length with a minimum of 525 words. Students will give their speeches in class. They should be sure to have their speeches memorized well enough so they do not need any prompts. Please be aware that students who need frequent prompting will receive a low grade. Also, any student with a speech that doesn’t meet the minimum requirement will receive a “D” or “F.” Students must portray a different character each year. One of the goals of this assignment is to help our children learn about different men and women who have made America great. Help your child choose characters from whom they can learn much. -

Dr. Sperling Blasts Kerr for Remarks

San n1E- Request Voucher Po- Today's Weather and Santa t Lira : No rain Students receising benefit% un- ar- today and tomorrow except der Public Law 634 (War go, light rain in extreme north; Orphans) should file souchers temperatures are expected to PARTAN I LY for November in the Regis- DA be near normal. Southwest trar's Office, ADM102 window winds 5-10 mph. SAN JOSE STATE COLLEGE No. 9. Vol. 63 1111110 SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA. MONDAY, DECEMBER 6, 1965 No. 48 Prof Blasts 'Make It Funny' e State College Dr. Sperling Blasts Hiring Policy Another Draft Story An SJS professor has accused By RICH THAW "You are hereby ordered for (c) deferment "might be ow state college administrators of en- Kerr for Remarks Spartan Daily Saigon(?) induction into the Armed Forces in the afternon mailing." couraging the hiring of student Corespondent of the United States, and to re- The opening to the featur, Dr. John Sperling, SJS assistant puses to institute sununer pro- ally, we will support it. If it does instructors to teach classes that Says the Editor: port at 1654 The Alameda, San story might be "A funny thin. professor of humanities, has ac- grams. not, we will insist on changes or should be taught by more experi- "Thaw, write another story Jose, California, on Dec. 15, happened to me on the way t, cused University of California Pres. Gov. Edmund Brown echoed the oppose it. We certainly will not enced professors, and the overload- on the draft. lalake it humorous. 1965 at 6 a.m. (morning). -

World Stage Curriculum

World Stage Curriculum Washington Irving’s Tour 1832 TEACHER You have been given a completed world stage and a world stage that your students can complete. This world stage is a snapshot of the world with Oklahoma, Cherokee Nation and Muscogee Creek Nation, at its center. The Pawnee, Comanche, and Kiowa were out to the west. Europe is to the north and east. Africa is to the south and east. South America is south and a bit east. Asia and the Pacific are to the west. Use a globe to show your students that these directions are accurate. Students - Directions 1. Your teacher will assign one of these actors to you. 2. After research, note the age of the actor in 1832, the year that Irving, Ellsworth, Pourtalès, and Latrobe took a Tour on the Oklahoma prairies. 3. Place the name and age of the actor in the right place on the World Stage. 4. Write a biographical sketch about the actor. 5. Make a report to the class, sharing the biographical sketch, the age of the actor in 1832, and the place the actor was at that time. 6. Listen to all the other reports and place all of the actors in their correct locations with their correct ages in 1832. Students - Information 1. The majority of the characters can be found in your public library in biographies and encyclopedia. You will need a library card to access this information. There is enough information about each actor for a biographical sketch. 2. Other actors can be found on the Internet. -

Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality George M

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The University of Montana: Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality George M. Dennison 2017 The University of Montana: Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality George M. Dennison Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/theuniversityofmontana Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dennison, George M., "The University of Montana: Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality" (2017). The University of Montana: Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality. 1. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/theuniversityofmontana/1 This Manuscript is brought to you for free and open access by the George M. Dennison at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Montana: Institutional Mythology and Historical Reality by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA: INSTITUTIONAL MYTHOLOGY AND HISTORICAL REALITY by George M. Dennison President and Professor Emeritus Senior Fellow The Carroll and Nancy O'Connor Center for the Rocky Mountain West The University of Montana 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..P. 3 VOLUME I INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………………..P. 12 CHAPTER I: THE FORMATIVE YEARS, 1893-1916..……………………………………………P. 41 CHAPTER II: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR THE FUTURE, 1916-1920………..….P. 136 CHAPTER III: THE MULTI-CAMPUS UNIVERSITY, 1921-1935…………….………………..P. 230 VOLUME II CHAPTER IV: THE INSTITUTIONAL CRISIS, WORLD WAR II, AND THE ABORTIVE EFFORT TO RE-INVENT THE MULTI-CAMPUS UNIVERSITY…….………….P. 1 CHAPTER V: MODERNIZATION AND GRADUATE EXPANSION, 1946-1972……………P. CHAPTER VI: THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA AND THE MONTANA UNIVERSITY SYSTEM, 1972-1995………………………………………………………………………….P. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected]

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University ETSU Faculty Works Faculty Works 1-1-2016 Mountain Men on Film Kenneth Estes Hall East Tennessee State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Citation Information Hall, Kenneth Estes. 2016. Mountain Men on Film. Studies in the Western. Vol.24 97-119. http://www.westernforschungszentrum.de/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETSU Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mountain Men on Film Copyright Statement This document was published with permission from the journal. It was originally published in the Studies in the Western. This article is available at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University: https://dc.etsu.edu/etsu-works/596 Peter Bischoff 53 Warshow, Robert. "Movie Chronicle: The Western." Partisan Re- view, 21 (1954), 190-203. (Quoted from reference number 33) Mountain Men on Film 54 Webb, Walter Prescott. The Great Plains. Boston: Ginn and Kenneth E. Hall Company, 1931. 55 West, Ray B. , Jr., ed. Rocky Mountain Reader. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1946. 56 Westbrook, Max. "The Authentic Western." Western American Literatu,e, 13 (Fall 1978), 213-25. 57 The Western Literature Association (sponsored by). A Literary History of the American West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1987. -

Download This

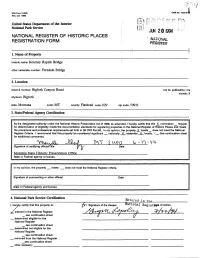

'/•""•'/• fc* NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-00 (Rev. Oct 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUN20I994 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES NATIONAL REGISTRATION FORM REGISTER 1. Name of Property historic name: Kearney Rapids Bridge other name/site number: Ferndale Bridge 2. Location street & number: Bigfork Canyon Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: X cityAown: Bigfork state: Montana code: MT county: Rathead code: 029 zip code: 59911 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally X statewide X locally. (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title \fjF~ Date Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification Entered in t I, hereby certify that this property is: Signature of the Keeper National Begistifte of Action ^/entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): ___________ Kcarnev Rapids Bridge Flathead County. -

Tough Paradise-Book Summaries

WHY AM I READING THIS? In 1995 the Idaho Humanities Council received an Exemplary Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct a special project highlighting the literature of Idaho and the Intermountain West. “Tough Paradise” explores the relationships between place and human psychology and values. Representing various periods in regional history, various cultural groups, various values, the books in this theme highlight the variety of ways that humans may respond to the challenging landscape of Idaho and the northern Intermountain West. Developed by Susan Swetnam, Professor of English, Idaho State University (1995) Book List 1. Balsamroot: A Memoir by Mary Clearman Blew 2. Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter by Janet Campbell Hale 3. Buffalo Coat by Carol Ryrie Brink 4. Heart of a Western Woman by Leslie Leek 5. Hole in the Sky by William Kittredge 6. Home Below Hell’s Canyon by Grace Jordan 7. Honey in the Horn by H. L. Davis 8. Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson 9. Journal of a Trapper Osborne Russell 10. Letters of a Woman Homesteader by Elinore Pruitt Stewart 11. Lives of the Saints in Southeast Idaho by Susan H. Swetnam 1 12. Lochsa Road by Kim Stafford 13. Myths of the Idaho Indians by Deward Walker, Jr. 14. Passages West: Nineteen Stories of Youth and Identity by Hugh Nichols 15. Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place by Terry Tempest Williams 16. Sheep May Safely Graze by Louie Attebery 17. Stories That Make the World by Rodney Frey 18. Stump Ranch Pioneer by Nelle Portrey Davis 19. -

Legend of Hugh Glass

Legend of Hugh Glass The story of Hugh Glass ranks as one of the most remarkable stories of survival in American history. So much so, that Hugh Glass became a legend in his own time. Little is actually known about Glass. It was said that he was a former pirate who gave up his life at sea to travel to the West as a scout and fur trapper. Exactly when is unknown. He is believed to have been born in Philadelphia around 1783. He had already been in the Western wilderness for several years when he signed on for an expedition up the Missouri River in 1823 with the company of William Ashley and Andrew Henry. The expedition used long-boats similar to those used by Lewis and Clark 19 years earlier to ascend the Missouri as far as the Grand River near present-day Mobridge, SD. There Glass along with a small group of men led by Henry started overland toward Yellowstone. At a point about 12 miles south of Lemmon, SD, now marked by a small monument, Glass surprised a grizzly bear and her two cubs while scouting for the party. He was away from the rest of the group at the time and the grizzly attacked him before he could fire his rifle. Using only his knife and bare hands, Glass wrestled the full-grown bear to the ground and killed it, but in the process he was badly mauled and bitten. His companions, hearing his screams, arrived on the scene to see a bloody and badly maimed Glass barely alive and the bear lying on top of him. -

Rocky Boy's Reservation Timeline

Rocky Boy’s Reservation Timeline Chippewa and Cree Tribes March 2017 The Montana Tribal Histories Reservation Timelines are collections of significant events as referenced by tribal representatives, in existing texts, and in the Montana tribal colleges’ history projects. While not all-encompassing, they serve as instructional tools that accompany the text of both the history projects and the Montana Tribal Histories: Educators Resource Guide. The largest and oldest histories of Montana Tribes are still very much oral histories and remain in the collective memories of individuals. Some of that history has been lost, but much remains vibrant within community stories and narratives that have yet to be documented. Time Immemorial – “This is an old, old story about the Crees (Ne-I-yah-wahk). A long time ago the Indians came from far back east (Sah-kahs-te-nok)… The Indians came from the East not from the West (Pah-ki-si-mo- tahk). This wasn’t very fast. I don’t know how many years it took for the Indians to move West.” (Joe Small, Government. Ethnic Heritage Studies Program: Plains Indians, Cheyenne-Cree-Crow-Lakota Sioux. Bozeman, MT: Center for Bilingual/Multicultural Education, College of Education, Montana State University, 1982. P. 4) 1851 – Treaty with the Red Lake and Pembina Chippewa included a land session on both sides of the Red River. 1855 – Treaty negotiated with the Mississippi, Pillager, and Lake Winnibigoshish bands of Chippewa Indians. The Tribes ceded a portion of their aboriginal lands in the Territory of Minnesota and reserved lands for each tribe. The treaty contained a provision for allotment and annuities. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

glacier. (It is but a few miles north to where Hudson River rock dips under upper silurian.) Evidences that they are masses of Drift are found in the irregular way in which the rocks lie at all angles, and in the fact that where the lower rock is exposed in the cut the under side is glaciated as if by moving over other rocks. Relation of Kings county traps to those <>i Cumberland county, N. S. By V. F. Marsters. An account of vegetable and mineral substances that fell in a snow storm in LaPorte county, Jan. 8-9, '92. By A. X. Somers. Some points in the geology of Mt. Orizaba. By J. T. Scovell, British Columbia glaciers. By C. H. Eigenmann. An account was given of the ascent of "The Glacier" in the Sel kirks in British Columbia. A number of photographs were shown of the foot of the glacier. Two-ocean pass. By Barton W. Evermann. [ Abstract.] It was probably in Pliocene times that the great lava-flow occurred in the region now known as the Yellowstone National Park, which covered hundreds of square miles of a large mountain valley with a vast sheet of rhyolite hundreds, perhaps in places, thousands of feet thick. It is certain that such streams and lakes as may have exis'ed there were wiped out of existence, and all terrestrial and aquatic life destroyed. It must have been many long years before this lava became sufficiently cooled to permit the formation of new streams ; but a time finally came when the rains, 31 falling upon the gradually cooling rock, were no longer converted into steam and thrown back into the air, only to condense and fall again, but being able to remain in liquid form upon the rock, sought lower levels, and thus new streams began to flow.