Hari Hari a Study of Land Use and a Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

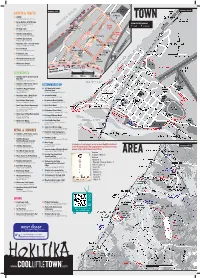

Hokitika Maps

St Mary’s Numbers 32-44 Numbers 1-31 Playground School Oxidation Artists & Crafts Ponds St Mary’s 22 Giſt NZ Public Dumping STAFFORD ST Station 23 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 7448 TOWN Oxidation To Kumara & 2 1 Ponds 48 Gorge Gallery at MZ Design BEACH ST 3 Greymouth 1301 Kaniere Kowhitirangi Rd. TOWN CENTRE PARKING Hokitika Beach Walk Walker (03) 755 7800 Public Dumping PH: HOKITIKA BEACH BEACH ACCESS 4 Health P120 P All Day Park Centre Station 11 Heritage Jade To Kumara & Driſt wood TANCRED ST 86 Revell St. PH: (03) 755 6514 REVELL ST Greymouth Sign 5 Medical 19 Hokitika Craſt Gallery 6 Walker N 25 Tancred St. (03) 755 8802 10 7 Centre PH: 8 11 13 Pioneer Statue Park 6 24 SEWELL ST 13 Hokitika Glass Studio 12 14 WELD ST 16 15 25 Police 9 Weld St. PH: (03) 755 7775 17 Post18 Offi ce Westland District Railway Line 21 Mountain Jade - Tancred Street 9 19 20 Council W E 30 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8009 22 21 Town Clock 30 SEAVIEW HILL ROAD N 23 26TASMAN SEA 32 16 The Gold Room 28 30 33 HAMILTON ST 27 29 6 37 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8362 CAMPCarnegie ST Building Swimming Glow-worm FITZHERBERT ST RICHARDS DR kiosk S Pool Dell 31 Traditional Jade Library 34 Historic Lighthouse 2 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 5233 Railway Line BEACH ST REVELL ST 24hr 0 250 m 500 m 20 Westland Greenstone Ltd 31 Seddon SPENCER ST W E 34 Tancred St. PH: (03) 755 8713 6 1864 WHARF ST Memorial SEAVIEW HILL ROAD Monument GIBSON QUAY Hokitika 18 Wilderness Gallery Custom House Cemetery 29 Tancred St. -

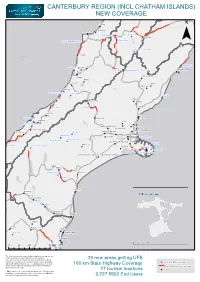

INCL CHATHAM ISLANDS) NEW COVERAGE ! ! Fairhall Granity !

CANTERBURY REGION (INCL CHATHAM ISLANDS) NEW COVERAGE ! ! Fairhall Granity ! Waimangaroa ! Carters Beach ! ! Lake Rotoroa Buller Gorge ! ! ! St Arnaud ! Maruia Falls Charleston GlowWorm Cave ¯ ! Blue Lake/ Lake Rotoroa ! ! Punakaiki ! Mangamaunu Ahaura Rapahoe Blackball ! ! ! Lewis Pass ! Entrances/exits to St Jam es Trail South Kaikoura Taylorville ! ! Hanmer Springs Dobson ! Moana ! Kumara Waiau ! Rotherham ! ! Kaniere ! Lake Mahinapua Lake Kaniere ! ! Gore Bay ! Ross Hawarden ! Arthurs Pass ! Waikari ! ! ! Pukekura Bealey ! Waipara ! Hari Hari ! Leithfield ! Okarito Lagoon ! Castle Hill ! Leithfield Beach ! Whataroa ! ! Cust ! Tuahiwi Lake Wahapo ! Waddington/Sheffield ! ! Mandeville ! West Eyreton ! Franz Josef/Waiau ! Belfast (Clearwater) Lake Heron Coalgate/Glentunnel Fox Glacier ! ! ! ! Kirwee Hornby Quadrant Mount Potts ! Hororata ! Taylors Mistake ! ! Lake Clearwater Prebbleton 1 ! ! Mount Sunday ! ! Jacobs River Dunsandel Prebbleton 2 TaiTapu ! ! ! Okains Bay Mt Somers Bruce Bay Tasman Glacier walks ! ! Doyleston Duvauchelle ! ! Little River ! ! ! Le Bons Bay ! ! Birdlings Flat ! Little River Takamatua Fairton/Ashburton Airport area and Ashburton Northpark ! Fairlie ! Limestone Valley Winchester ! ! ! Albury Pareora Omarama ! ! Otematata ! Waitaki Lakes area ! Kurow ! ! Duntroon ! Glenavy ! Naseby ! Omakau ! Ranfurly ! Maheno ! Moa Creek ! Taranui/Kakanui ! Hampden ! ! Moeraki Trotters Gorge 0 20 40 80 KM ! Palmerston ! *The blue tourism areas and red State Highway coverage on this map are indicative, representing coverage expected to be achieved with the first $150 million provided to the Rural 39 new areas getting UFB Connectivity Group (RCG). The RCG contract will be expanded ! Tourism New Cove rage* with another $100 m illion to cover remaining tourism areas (not 100 km State Highway Coverage shown on this map) and remaining State Highway blackspots State Highway New Coverage* (not shown on this map). ! UFB2+ **RBI2 end users are households and businesses. -

Wetlands Resource Has Been Developed to Encourage You and Your Class to Visit Wetlands in Your ‘Backyard’

WETLANDS for Education in the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservancy January 2005 Edition 2 WETLANDS for Education in the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservancy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A large number of people have been involved in the production and editing of this resource. We would like to thank them all and in particular the following: Area and Conservancy staff, especially Philippe Gerbeaux for their comments and assistance. Te Rüanga o Ngäi Tahu, Te Rünaka o Makäwhio and Te Rünaka o Ngäti Waewae for their comments and assistance through Rob Tipa. Compiled by Chrisie Sargent, Sharleen Hole and Kate Leggett Edited by Sharleen Hole and Julie Dutoit Illustrations by Sue Asplin ISBN 0-478-22656-X 2nd Edition January 2005 Published by: Department of Conservation Greymouth Mawheranui Area Office PO Box 370 Greymouth April 2004 CONTENTS USING THIS RESOURCE 5 THE CURRICULUM 5 WHY WETLANDS? 8 RAMSAR CONVENTION 9 SAFETY 9 BE PREPARED ACTIVITY 10 PRE VISIT ACTIVITIES 11 POST VISIT ACTIVITIES 12 FACT SHEETS What is a wetland? 15 Types of wetlands 17 How wetlands change over time 19 Threats to wetlands 21 Wetland uses & users 23 The water cycle is important for wetlands 24 Catchments 25 Water quality 27 Invertebrates 29 Wetland soils 30 Did you know that coal formed from swamps? 31 Wetland plants 32 Wetland fish 33 Whitebait-what are they? 34 Wetland birds 35 Food chains & food webs 37 Wetlands - a 'supermarket' for tai poutini maori 39 ACTIVITY SHEETS Activity 1: What is . a wetland? 43 Activity 2: What is . a swamp? 44 Activity 3: What is . an estuary? 45 Activity 4: What is . -

The New Zealand Gazette. 497

MAR. 4.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 497 MILITARY DISTRICT No. 9 ,(NELSON)--oontmued. MILITARY DISTRICT No. 9 (NELSON)--oontinued. 383641 Home, Earl Reid, religious worker, Greenwood St., Motueka. 284958 Johnston, John Marcus, herd-tester, Budge St., Blenheim. 271736 Hooper, Vernon Graham, grocer's assistant, Wakefield, 287372 Johnstone, John Murdoch Sidney Merewether, engineer and Nelson. fitter, North Revell St., Hokitika. 427329 Hope, Harry Beresford, stores labourer, Public Works De 265106 Johnstone, John Smith, orchard worker, Haslep Rd., Tasman partment, Bruce Bay, South Westland. RurA.1 Mail Delivery, Upper Moutere. 261221 Hope, Pat McKellar, shepherd and drover, Deep Bay, French 425997 Jones, Edward Lloyd, miner, 17 Richmond St., Cobden, Pass. Greymouth. 276659 Hopgood, Walter Francis, lime-worker, Cape Foulwind. 276757 Jones, Frederick; loco-driver, Granity. 426079 Hopley, William James, coal-miner, Dawson's Hotel, 249413 Jones, George William, bus-driver, Premier Garage, Grey Reefton. mouth. 286081 Hornal, Robert James, miner, Wallsend, Brunnerton. 285309 Jones, Innes Ralph Rutland, dairy-farm!'r, Havelock, Marl- 177942 Hornby, William Charles, sawmiller, Ruru, West Coast. borough. 287125 Horne, Douglas Louis, builder, care of Hannah and Dyer, 238937 Jones, Jack, yard hand, Moorehouse St., Ross. Builders, Mental Hospital, Hokitika. 287458 Jones, Lemuel David, labourer, Jackson's Bay. 427260 Hornell, Arthur Thomas, timber-worker, Karangarua, South 264592 Jones, 'William Peter, farm labourer, Kokatahi. · Westland. 426688 Jope, George Edwa.rd, lorry-driver, Cape Foulwind. 050884 Horner, James Muir, farm-assistant, Murchison. 426061 Jope, Thomas Richard, labourer, care of Mr. A. E. Taylor, 233611 Horrell, Norman Nelson, sawmill hand, Upper Moutere Disraeli St., Westport. Rural Delivery. 373503 Jordan, Frederick Williams, constable, Hokitika. -

FT1 Australian-Pacific Plate Boundary Tectonics

Geosciences 2016 Annual Conference of the Geoscience Society of New Zealand, Wanaka Field Trip 1 25-28 November 2016 Tectonics of the Pacific‐Australian Plate Boundary Leader: Virginia Toy University of Otago Bibliographic reference: Toy, V.G., Norris, R.J., Cooper, A.F., Sibson, R.H., Little, T., Sutherland, R., Langridge, R., Berryman, K. (2016). Tectonics of the Pacific Australian Plate Boundary. In: Smillie, R. (compiler). Fieldtrip Guides, Geosciences 2016 Conference, Wanaka, New Zealand.Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 145B, 86p. ISBN 978-1-877480-53-9 ISSN (print) : 2230-4487 ISSN (online) : 2230-4495 1 Frontispiece: Near-surface displacement on the Alpine Fault has been localised in an ~1cm thick gouge zone exposed in the bed of Hare Mare Creek. Photo by D.J. Prior. 2 INTRODUCTION This guide contains background geological information about sites that we hope to visit on this field trip. It is based primarily on the one that has been used for University of Otago Geology Department West Coast Field Trips for the last 30 years, partially updated to reflect recently published research. Copies of relevant recent publications will also be made available. Flexibility with respect to weather, driving times, and participant interest may mean that we do not see all of these sites. Stops are denoted by letters, and their locations indicated on Figure 1. List of stops and milestones Stop Date Time start Time stop Location letter Aim of stop Notes 25‐Nov 800 930 N Door Geol Dept, Dunedin Food delivery VT, AV, Nathaniel Chandrakumar go to 930 1015 N Door Geology, Dunedin Hansens in Kai Valley to collect van 1015 1100 New World, Dunedin Shoping for last food supplies 1115 1130 N Door Pick up Gilbert van Reenen Drive to Chch airport to collect other 1130 1700 Dud‐Chch participants Stop at a shop so people can buy 1700 1900 Chch‐Flockhill Drive Chch Airport ‐ Flockhill Lodge beer/wine/snacks Flockhill Lodge: SH 73, Arthur's Pass Overnight accommodation; cook meal 7875. -

GNS Science Miscellaneous Series Report

NHRP Contestable Research Project A New Paradigm for Alpine Fault Paleoseismicity: The Northern Section of the Alpine Fault R Langridge JD Howarth GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 121 November 2018 DISCLAIMER The Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) and its funders give no warranties of any kind concerning the accuracy, completeness, timeliness or fitness for purpose of the contents of this report. GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any actions taken based on, or reliance placed on the contents of this report and GNS Science and its funders exclude to the full extent permitted by law liability for any loss, damage or expense, direct or indirect, and however caused, whether through negligence or otherwise, resulting from any person’s or organisation’s use of, or reliance on, the contents of this report. BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Langridge, R.M., Howarth, J.D. 2018. A New Paradigm for Alpine Fault Paleoseismicity: The Northern Section of the Alpine Fault. Lower Hutt (NZ): GNS Science. 49 p. (GNS Science miscellaneous series 121). doi:10.21420/G2WS9H RM Langridge, GNS Science, PO Box 30-368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand JD Howarth, Dept. of Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2018 www.gns.cri.nz ISSN 1177-2441 (print) ISSN 1172-2886 (online) ISBN (print): 978-1-98-853079-6 ISBN (online): 978-1-98-853080-2 http://dx.doi.org/10.21420/G2WS9H CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... IV KEYWORDS ......................................................................................................................... V KEY MESSAGES FOR MEDIA ............................................................................................ VI 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 7 2.0 RESEARCH AIM 1.1 — ACQUIRE NEW AIRBORNE LIDAR COVERAGE .............. -

West Coast Sexual Health Services

West Coast Sexual Health Services Listed below are some of the options for sexual health services available on the West Coast. Family Planning For appointments 0800 372 546 Family Planning Nurses can provide advice over the phone on ECP, contraception, and sexual health. Buller District Buller Sexual Health Clinic Outpatients Department (Buller Health) Specialist Sexual Health Service WESTPORT FREE service for all ages for assessment and 03 788 9030 ext 8756 (during clinic hours) treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. FREE Condoms. Drop-In Clinic and nurse-led Clinic hours appointments available. Mondays 10.30 to 11.30am. Drop-in Clinic hours Mondays 11.30am to 4.30pm Buller Health 45 Derby Street A Doctor, Rural Nurse Specialist and Practice WESTPORT Nurses provide medical services including sexual 03 788 9277 health. Appointments essential. Coast Medical 61 Palmerston Street A Doctor and Practice Nurses provide medical WESTPORT services including sexual health. Appointments 03 789 5000 essential. Karamea Medical Centre 126 Waverley Street A Rural Nurse Specialist and a Doctor provide KARAMEA medical services including sexual health. Available 03 782 6710 at various times. Appointments essential. Ngakawau Health Centre 1a Main Road A Rural Nurse Specialist and a Doctor provide HECTOR medical services including sexual health. Available 03 788 5062 at various times. Appointments essential. Reefton Integrated Family Health Centre 103 Shiel Street A Doctor, Rural Nurse Specialist and Practice REEFTON Nurses provide medical services including sexual 03 732 8605 health. Appointments essential. Grey District WCDHB Sexual Health Clinic Link Clinic (Grey Base Hospital) Specialist Sexual Health Service GREYMOUTH FREE service for all ages for assessment and 03 769 7400 extn 2874 (during clinic hours) treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections. -

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper for West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board

WEST COAST STATUS REPORT Meeting Paper For West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board TITLE OF PAPER STATUS REPORT AUTHOR: Mark Davies SUBJECT: Status Report for the Board for period ending 15 April 2016 DATE: 21 April 2016 SUMMARY: This report provides information on activities throughout the West Coast since the 19 February 2016 meeting of the West Coast Tai Poutini Conservation Board. MARINE PLACE The Operational Plan for the West Coast Marine Reserves is progressing well. The document will be sent out for Iwi comment on during May. MONITORING The local West Coast monitoring team completed possum monitoring in the Hope and Stafford valleys. The Hope and Stafford valleys are one of the last places possums reached in New Zealand, arriving in the 1990’s. The Hope valley is treated regularly with aerial 1080, the Stafford is not treated. The aim is to keep possum numbers below 5% RTC in the Hope valley and the current monitor found an RTC of 1.3% +/- 1.2%. The Stafford valley is also measured as a non-treatment pair for the Hope valley, it had an RTC of 21.5% +/- 6.2%. Stands of dead tree fuchsia were noted in the Stafford valley, and few mistletoe were spotted. In comparison, the Hope Valley has abundant mistletoe and healthy stands of fuchsia. Mistletoe recruitment plots, FBI and 20x20m plots were measured in the Hope this year, and will be measured in the Stafford valley next year. KARAMEA PLACE Planning Resource Consents received, Regional and District Plans, Management Planning One resource consent was received for in-stream drainage works. -

Franz Josef Glacier Township

Mt. Tasman Mt. Cook FRANZ JOSEF IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS www.glaciercountry.co.nz EMERGENCY Dial 111 POLICE (Franz Josef) 752 0044 D Franz Josef Health Clinic 752 0700 GLACIER TOWNSHIP Glacier The Visitor Centre at Franz Josef is open 7 days. I After hours information is available at the front I I entrance of the Visitor Centre/DOC offi ce. H Times given are from the start of track and are approximate I 1 A A. GLACIER VALLEY WALK 1 1 hour 20 mins return following the Waiho riverbed 2 20 G B to the glacier terminal. Please heed all signs & barriers. 14 B. SENTINEL ROCK WALK Condon Street 21 C 3 15 24 23 20 mins return. A steady climb for views of the glacier. 5 4 Cron Street 16 C. DOUGLAS WALK/PETERS POOL 25 22 43 42 12 26 20 mins return to Peter’s Pool for a fantastic 13 9 6 31 GLACIER E refl ective view up the glacier valley. 1 hour loop. 11 7 17 30 27 45 44 10 9 8 Street Cowan 29 28 ACCESS ROAD F D. ROBERTS POINT TRACK 18 33 32 Franz Josef 5 hours return. Climb via a rocky track and 35 33 State Highway 6 J Glacier Lake Wallace St Wallace 34 19 Wombat swingbridges to a high viewpoint above glacier. 40 37 36 Bus township to E. LAKE WOMBAT TRACK 41 39 38 Stop glacier carpark 40 State Highway 6 1 hour 30mins return. Easy forest walk to small refl ective pond. 46 is 5 km 2 hour F. -

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1

Overview of the Westland Cultural Heritage Tourism Development Plan 1. CULTURAL HERITAGE THEMES DEVELOPMENT • Foundation Māori Settlement Heritage Theme – Pounamu: To be developed by Poutini Ngāi Tahu with Te Ara Pounamu Project • Foundation Pākehā Settlement Heritage Theme – West Coast Rain Forest Wilderness Gold Rush • Hokitika - Gold Rush Port, Emporium and Administrative Capital actually on the goldfields • Ross – New Zealand’s most diverse goldfield in terms of types of gold deposits and mining methods • Cultural Themes – Artisans, Food, Products, Recreation derived from untamed, natural wilderness 2. TOWN ENVIRONMENT ENHANCEMENTS 2.1 Hokitika Revitalisation • Cultural Heritage Precincts, Walkways, Interpretation, Public Art and Tohu Whenua Site • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 2.2 Ross Enhancement • Enhancement and Experience Plan Development • Wayfinders and Directional Signs (English, Te Reo Māori, Chinese) 3. COMMERCIAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT • Go Wild Hokitika and other businesses at TRENZ 2020 • Chinese Visitor Business Cluster • Mahinapua Natural and Cultural Heritage Iconic Attraction 4. COMMUNITY OWNED BUSINESSES AND ACTIVITIES • Westland Industrial Heritage Park Experience Development • Ross Goldfields Heritage Centre and Area Experience Development 5. MARKETING • April 2020 KUMARA JUNCTION to GREYMOUTH Taramakau 73 River Kapitea Creek Overview of the Westland CulturalCHESTERFIELD Heritage 6 KUMARA AWATUNA Londonderry West Coast Rock Tourism Development Plan Wilderness Trail German Gully -

The Ecology of Whataroa Virus, an Alphavirus, in South Westland, New Zealand by J

J. Hyg., Camb. (1973), 71, 701 701 Printed in Great Britain The ecology of Whataroa virus, an alphavirus, in South Westland, New Zealand BY J. A. R. MILES Department of Microbiology, Medical School, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand (Received 6 March 1973) SUMMARY The findings of a survey on the ecology of an alphavirus over the years 1964-9 are reviewed. Evidence is presented to show that wild birds constitute a vertebrate reservoir of the virus and that mosquitoes, primarily Culiseta tonnoiri and Gulex pervigilans, which are both endemic New Zealand species, are responsible for summer transmission. Serological evidence of infection was obtained in all years and evidence is presented to indicate that the virus is enzootic rather than being reintroduced each spring. The number of birds with antibody increased before mosquitoes became active in the spring and possible explanations of this are discussed. The mean temperature in the hottest month in the study area is substantially below that in other areas with enzootic mosquito-borne viruses and experimental studies showed that Whataroa virus was able to replicate more rapidly in mos- quitoes at low temperatures than any arboviruses previously studied. The main natural focus of infection appeared to be in a modified habitat and the introduced song thrush (Turdus philomelos) to be the main vertebrate reservoir host. INTRODUCTION In New Zealand a number of rural summer epidemics of influenza-like disease suggestive of an arbovirus aetiology have occurred. Because of this a serological survey covering a variety of climatic and biological zones throughout the country was initiated in 1959-60. -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day.