The Legal Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fritz-Walter-Medaille 2016

FRITZ-WALTER-MEDAILLE 2016 INHALT FRITZ WALTER – EIN LEBEN FÜR DEN FUSSBALL 3 GRUSSWORT DFB 4 GRUSSWORT FRITZ-WALTER-STIFTUNG 5 DIE FRITZ-WALTER-MEDAILLE – EINE BESONDERE AUSZEICHNUNG FÜR HERAUSRAGENDE TALENTE 6 DIE PREISTRÄGER DER FRITZ-WALTER-MEDAILLE 7 DREAM-TEAM DER MÄNNER 8 DIE PREISTRÄGER 2016 10 INTERVIEW JOSHUA KIMMICH 16 DAS DREAM-TEAM DER FRAUEN 18 STIMMEN ZUR FRITZ WALTER – FRITZ-WALTER-MEDAILLE 20 OLYMPIA 2016 22 EIN LEBEN FÜR DEN FUSSBALL PREISTRÄGER 2015 24 PREISTRÄGER 2014 26 PREISTRÄGER 2013 28 GEBURTSTAG 31. Oktober 1920 in Kaiserslautern PREISTRÄGER 2012 30 TODESTAG 17. Juni 2002 PREISTRÄGER 2011 32 FAMILIENSTAND verheiratet mit Ehefrau Italia PREISTRÄGER 2010 34 VEREIN 1. FC Kaiserslautern von 1928 bis 20. Juni 1959 PREISTRÄGER 2009 36 (Abschiedsspiel gegen Racing Paris) PREISTRÄGER 2008 38 POSITION Halbrechts PREISTRÄGER 2007 40 PREISTRÄGER 2006 42 RÜCKENNUMMER 8 PREISTRÄGER 2005 44 LÄNDERSPIELE / TORE 61 / 33 – Weltmeister 1954 DIE FRITZ-WALTER-STIFTUNG 46 FCK-SPIELE / TORE 384 / 327 – Deutscher Meister 1951 und 1953 IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: AUSZEICHNUNGEN UND EHRUNGEN Deutscher Fußball-Bund Otto-Fleck-Schneise 6 · 60528 Frankfurt/Main 1953 Silbernes Lorbeerblatt (als erster Fußballer) www.dfb.de Fritz-Walter-Stiftung 1955 Goldene Ehrennadel des Deutschen Fußball-Bundes c/o Ministerium des Innern, für Sport und Infrastruktur des Landes Rheinland-Pfalz 1970 Großes Verdienstkreuz des Verdienstordens Schillerplatz 3-5 · 55116 Mainz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Fritz Walter ist der erste www.fritz-walter-stiftung.de Ehrenspielführer der Deutschen Verantwortlich für den Inhalt: 1975 Bundesverdienstkreuz mit Stern Nationalmannschaft und des 2 Ralf Köttker (DFB), Michael Desch (FWS) Redaktion: 1995 Verdienstorden des Fußball-Weltverbandes FIFA 1. -

Uefa Women's Champions League

UEFA WOMEN'S CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2015/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadio Città del Tricolore - Reggio Emilia Thursday 26 May 2016 VfL Wolfsburg 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Olympique Lyonnais Matchday 14 - Final Last updated 25/05/2016 03:07CET UEFA WOMEN'S CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 6 Match officials 8 Fixtures and results 10 Match-by-match lineups 13 Legend 16 1 VfL Wolfsburg - Olympique Lyonnais Thursday 26 May 2016 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Stadio Città del Tricolore, Reggio Emilia Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers VfL Wolfsburg - Olympique 23/05/2013 F 1-0 London Müller 73 (P) Lyonnais Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA VfL Wolfsburg 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 Olympique Lyonnais 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 VfL Wolfsburg - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Paris Saint-Germain - VfL 1-2 Kaci 6; Müller 71, 26/04/2015 SF Paris Wolfsburg agg: 3-2 Jakabfi 74 VfL Wolfsburg - Paris Saint- Delannoy 12 (P), Cruz 18/04/2015 SF 0-2 Wolfsburg Germain Traña 26 Olympique Lyonnais - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Women's Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Olympique Lyonnais - 1. -

Vfl Wolfsburg Mi, 3

Nr. 9 SAISON 2019/20 VfL Wolfsburg Mi, 3. Juni 2020 // DFB-Pokal Viertelfi nale 19:00 Uhr // Tönnies-Arena www.fsv-gt.net Liebe Freunde des Frauenfußballs, es sind denkwürdige und außergewöhnliche Einsatz und Leidenscha alle ungewöhnli- Zeiten. Die Corona-Pandemie hat gravie- chen Maßnahmen mitgemacht haben, sodass rende Einschnitte in unser gesell- die Partie heute angep en werden scha liches Leben vorgenom- kann. Mein Dank gilt ferner Ihnen men und auch der Frauenfuß- als Freunde, Verwandte, Eltern, ball ist davon nicht verschont Unterstützer und Fans, die uns geblieben. So wurde die Spiel- weiterhin den Rücken stärken und zeit 2019/20 in der letzten Wo- die mit ihrem persönlichen En- che beendet. Umso mehr freu- gagement und Verständnis unseren en wir uns, dass nun im Rahmen Spielerinnen einen sicheren Rück- der Lockerungen zumindest noch halt geben. Auch an unsere U17-Mann- das Viertel nale des DFB-Pokals statt- scha geht der Dank, aus deren Mitte hilfs- nden kann. Dazu mussten unsere Spielerin- bereite Spielerinnen unseren Personalkader nen und der gesamte Betreuerstab allerdings für das Pokalspiel ergänzen. Und zu guter einen immensen organisatorischen Aufwand Letzt möchte ich mich bei allen Sponsoren betreiben, um die Bedingungen für die Teil- bedanken, die uns erneut die gesamte Saison nahme einzuhalten. Damit ist dieses Vier- so tatkrä ig unterstützt haben und die uns tel nale gegen den Deutschen Meister VfL auch in diesen schweren Krisenzeiten weiter Wolfsburg schon jetzt auch ein historischer begleiten und auf diverse Weise helfen wol- Moment in der jungen Geschichte des FSV len. Gütersloh. Dafür möchte ich mich zunächst bei unse- Mit sportlichen Grüßen verbleibt ren Spielerinnen bedanken, die mit großem Ihr Michael Horstkötter STARKER SERVICE • Reifenservice • Inspektion HU/AU • Unfallabwicklung • Mietwagen • Zubehör u.v.m. -

The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Dissertations Theses & Dissertations Fall 10-2017 The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes Christopher James Kohl Lindenwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons Recommended Citation Kohl, Christopher James, "The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes" (2017). Dissertations. 199. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/dissertations/199 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses & Dissertations at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Academic and Behavioral Impact of Multiple Sport Participation on High School Athletes by Christopher James Kohl October, 2017 A Dissertation submitted to the Education Faculty of Lindenwood University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education School of Education Acknowledgements I would like to thank my wife, Ashley, for her loving support through this process. I would also like to thank my children, Adam and Grace, for being patient with Daddy while he “works on his paper.” My appreciation goes to Dr. Hanson, Dr. Henderson, and my committee for all of the guidance and direction they provided through this adventure. The inspiration for this work was fueled by all of the student athletes I have seen who should have been encouraged to participate in multiple sports and by my grandfather, Joseph Edward, who always encouraged me to do my best. -

2014 Women's Soccer Guide.Indd Sec1:87 10/17/2014 12:43:12 PM Bbuffsuffs Inin Thethe Leagueleague

BBuffsuffs InIn thethe LeagueLeague Th e National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) is the top level professional women’s soccer league in the United States. It began play in spring 2013 with eight teams: Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, FC Kansas City, Portland Th orns FC, Seattle Reign FC, Sky Blue FC, the Washington Spirit and the Western New York Flash. Th e Houston Dash joined the league in 2014. Based in Chicago, the NWSL is supported by the United States Soccer Federation, Canadian Soccer Association and Federation of Mexican Football. Each of the league’s nine clubs will play a total of 24 games during a 19-week span, with the schedule beginning the weekend of April 12-13 and concluding the weekend of Aug. 16-17. Th e top four teams will qualify for the NWSL playoff s and compete in the semifi nals on Aug. 23-24. Th e NWSL will crown its inaugural champion aft er the fi nal on Sunday, Aug. 31. Nikki Marshall (2006-09): Defender, Portland Th orns FC At Colorado: Holds 20 program records ... Th e all-time leading scorer with 42 goals ... Leads the program with 93 points, 18 game-winning goals and 261 shots attempted ... Set class records as a freshman and sophomore with 17 and nine goals, respectively ... Scored the fastest regulation and overtime goals in CU history, taking less than 30 seconds to score against St. Mary’s College in 2009 (8-1) and against Oklahoma in 2007 (2-1, OT) ... Ranks in the top 10 in 32 other career, season and single game categories .. -

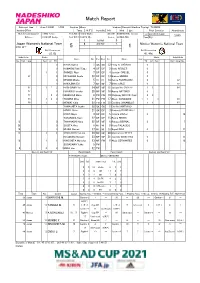

Match Report

Japan Football Association Match Report MS&AD CUP 2021 Date and Time June 13,2021 14:02Duration 90min Stadium Kanseki Stadium Tochigi,TOCHIGI Weather Fine Temp 29.5℃ Humidity 39% Wind Light Pitch Condition Attendances Match Commissioner HIRAI Tetsu Asst.Ref.1 HAGIO Maiko 4th Off. KANEMATSU Haruna Lawn Excellent Lawn 3,890 Referee KOIZUMI Asaka Asst.Ref.2 OGATA Mio Scorer HONDA Miki Damp Dry 1 1st Half 0 Japan Women's National Team 42nd Half 1 Mexico Women's National Team KICK OFF 5 1 Ball Possession Ball Possession 52.6% 47.4% Substitute Shots Shots Substitute Goal Name No.Pos. Pos. No. Name Goal No.OUT Time 2nd 1st Ttl Ttl 1st 2ndOUT Time No. 0 IKEDA Sakiko 1 GK GK 12 Emily ALVARADO 0 0 KUMAGAI Saki (Cap.) 4 DF DF 2 Kenti ROBLES 0 1 1 SHIMIZU Risa 2 DF DF 4 Jocelyn OREJEL 0 81' 0 MIYAGAWA Asato 16 DF DF 13 Bianca SIERRA 0 0 MINAMI Moeka 5 DF DF 14 Karina RODRIGUEZ 0 52' 0 NAKAJIMA Emi 7 MF MF 7 Belen CRUZ 0 77' 81' 1 1 2 HASEGAWA Yui 14 MF MF 11 Jacqueline OVALLE 1 1 84' 71' 0 HAYASHI Honoka 20 MF MF 16 Nancy ANTONIO 0 71' 2 2 1 IWABUCHI Mana 8 FW FW 10 Stephany MAYOR (Cap.) 2 2 58' 1 2 3 1 TANAKA Mina 11 FW FW 17 Alison GONZALEZ 1 1 1 84' 58' 1 1 1 MOMIKI Yuka 10 FW FW 18 Carolina JARAMILLO 1 1 63' YAMASHITA Ayaka 18 GK GK 1 Cecilia SANTIAGO HIRAO Chika 21 GK DF 3 Kimberly RODRIGUEZ DOKO Mayo3 DF DF 5 Jimena LOPEZ 0 14 TAKARADA Saori 22 DF DF 15 Reyna REYES 16 0 TAKAHASHI Hana15 DF MF 6 Rebeca BERNAL 0 7 20 0 SUGITA Hina 6 MF MF 8 Kiana PALACIOS 14 0 MIURA Narumi17 MF MF 19 Nayeli DIAZ 0 17 11 1 1 SHIOKOSHI Yuzuho 19 MF MF 20 Maricarmen REYES KITAMURA Nanami 23 MF MF 21 Joseline MONTOYA 0 11 10 1 1 1 KINOSHITA Momoka 13 MF FW 9 Alicia CERVANTES 0 18 SUGASAWA Yuika 9 FW 8 2 2 1 ENDO Jun 12 FW Caution and Sent-off Head Coach Head Coach Caution and Sent-off TAKAKURA Asako Monica VERGARA 2nd 1st Team Total 1st 2nd 8 5 13Shots 5 4 1 2 3 5GK 11 4 7 0 2 2CK 7 4 3 1 3 4Dir.FK 4 2 2 0 0 0Ind.FK 1 1 0 0 0 0(Off-side) 1 1 0 0 0 0PK 0 0 0 Time Team No. -

SLOVENSKO - NEMECKO KVALIFIKÁCIA MS 2015 2 | Oficiálny Bulletin NÁŠ SÚPER

Základné vyhotovenie „circle dark“ Základné vyhotovenie „circle dark“ SLOVENSKO - NEMECKO KVALIFIKÁCIA MS 2015 2 | Oficiálny bulletin NÁŠ SÚPER Deutscher Fussbal-Bund dfb.de Prezident: Wolfgang NIERSBACH Generálny sekretár: Helmut SANDROCK Rok založenia: 1900 Člen FIFA od: 1904 Člen UEFA od: 1954 FIFA ranking: 2 KÁDER BRANKÁRKY Almuth SCHULT 09.02.1991 Vfl Wolfsburg Laura BENKARTH 14.10.1992 SC Freiburg OBRANKYNE Bianca SCHMIDT 23.01.1990 1. FFC Frankfurt Saskia BARTUSIAK 09.09.1982 1. FFC Frankfurt Linda BRESONIK 07.12.1983 Paris St. Germain (Francúzsko) Leonie MAIER 29.09.1992 FC Bayern München Annike KRAHN 01.07.1985 Paris St. Germain (Francúzsko) Tabea KEMME 14.12.1991 1. FFC Turbine Potsdam STREDOPOLIARKY Simone LAUDEHR 12.07.1986 1. FFC Frankfurt Melanie BEHRINGER 18.11.1985 1. FFC Frankfurt Nadine KESSLER 04.04.1988 VfL Wolfsburg Melanie LEUPOLZ 14.04.1994 SC Freiburg Fatmire BAJRAMAJ 01.04.1988 1. FFC Frankfurt Sara DÄBRITZ 15.02.1995 SC Freiburg ÚTOČNÍČKY Dzsenifer MAROSZAN 18.04.1992 1. FFC Frankfurt Anja MITTAG 16.05.1985 LdB FC Malmö Celia ŠAŠIĆ 27.06.1988 1. FFC Frankfurt Alexandra POPP 06.04.1991 VfL Wolfsburg Hlavná trénerka: Silvia NEID NEMECKO Oficiálny bulletin | 3 Kvalifikácia MS 2015 v Kanade Nemecko - Rusko 9:0 (Kessler 2, Maroszán 2, Šašić, Bajramaj, Leupolz, Goessling, Schmidt) Írsko - SLOVENSKO 2:0 (Russell, D. O‘Sullivan) Chorvátsko – Írsko 1:1 (Calwell (vl.) - Scurich (vl.) SLOVENSKO – Slovinsko 1:3 (Škorvánková – Rybárová (vl.), Nikl, Zver) Chorvátsko – SLOVENSKO 0:1 (Bartovičová) Slovinsko – Nemecko 0:13 (Šašić 3, Mittag 3, Goessling 2, Maier, Krahn, Laudehr, Bajramaj, Popp) Slovinsko – Írsko 0:3 (F. -

2020 UNC Women's Soccer Record Book

2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book 1 2020 UNC Women’s Soccer Record Book Carolina Quick Facts Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. 2020 UNC Soccer Media Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents, Quick Facts........................................................................ 2 Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2019 Roster, Pronunciation Guide................................................................... 3 2020 Schedule................................................................................................. 4 Enrollment: 18,814 undergraduates, 11,097 graduate and professional 2019 Team Statistics & Results ....................................................................5-7 students, 29,911 total enrollment Misc. Statistics ................................................................................................. 8 Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz Chancellor: Losses, Ties, and Comeback Wins ................................................................. 9 Bubba Cunningham Director of Athletics: All-Time Honor Roll ..................................................................................10-19 Larry Gallo (primary), Korie Sawyer Women’s Soccer Administrators: Year-By-Year Results ...............................................................................18-21 Rich (secondary) Series History ...........................................................................................23-27 Senior Woman Administrator: Marielle vanGelder Single Game Superlatives ........................................................................28-29 -

1998 NCAA Champions •20 NCAA Championship Appearances 14-Time SEC Champions ▪1996, ’97, ’98, ’99, ’00, ’01, ’06, ’07, ’08, ’09, ’10, ’12, ’13, ‘15

1998 NCAA Champions •20 NCAA Championship Appearances 14-time SEC Champions ▪1996, ’97, ’98, ’99, ’00, ’01, ’06, ’07, ’08, ’09, ’10, ’12, ’13, ‘15 Today’s Match: What’s Happening? Florida (7-9-4, 4-4-2 SEC) versus Arkansas (12-4-3, 6-3-1 SEC) Two teams meet again in the span of a week Thursday when the Gators face Arkansas in 2018 Date & Time: Thursday, Nov. 1 at 4:30 p.m. ET Southeastern Conference Tournament semifinal play. Site: Orange Beach Sportsplex (1,500) The Coaches: Becky Burleigh, 29th season overall (496-142-42) Florida has advanced to the SEC Tournament each year of the program’s history, winning 12 titles and 24th season at UF (414-119-36/UF), Colby Hale, seventh including the 2015 and 2016 crowns. This is the sixth time the two teams play in SEC Tournament season overall and at Arkansas (70-56-15) action and the first semifinal meeting. The two teams last met during tournament play in the 2016 final, Series Record: UF leads 22-1 with UF taking a 2-1 overtime win. Television: SEC Network Radio: ESPN Gainesville 98.1 FM / 850 AM When the two teams met last Thursday in Gainesville for the regular-season finale, Florida took a 3-0 th Streaming video: SEC Network win over Arkansas. Senior Briana Solis gave UF an early lead with a 20-yard strike in the 10 minute. Internet: live stats and audio for UF vs. Arkansas match available Deanne Rose hit her first two goals of 2018 within a four-minute second-half span to give her four double goal matches in her two seasons as a Gator. -

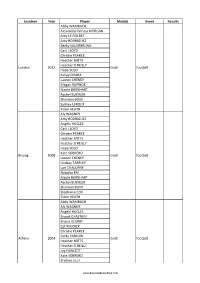

List of All Olympics Prize Winners in Football in U.S.A

Location Year Player Medals Event Results Abby WAMBACH Alexandra Patricia MORGAN Amy LE PEILBET Amy RODRIGUEZ Becky SAUERBRUNN Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY London 2012 Gold football Hope SOLO Kelley OHARA Lauren CHENEY Megan RAPINOE Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Sydney LEROUX Tobin HEATH Aly WAGNER Amy RODRIGUEZ Angela HUCLES Carli LLOYD Christie PEARCE Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Hope SOLO Kate SOBRERO Beijing 2008 Gold football Lauren CHENEY Lindsay TARPLEY Lori CHALUPNY Natasha KAI Nicole BARNHART Rachel BUEHLER Shannon BOXX Stephanie COX Tobin HEATH Abby WAMBACH Aly WAGNER Angela HUCLES Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Cat REDDICK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Athens 2004 Gold football Heather MITTS Heather O REILLY Joy FAWCETT Kate SOBRERO Kristine LILLY www.downloadexcelfiles.com Lindsay TARPLEY Mia HAMM Shannon BOXX Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carla OVERBECK Christie PEARCE Cindy PARLOW Danielle SLATON Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kate SOBRERO Sydney 2000 Silver football Kristine LILLY Lorrie FAIR Mia HAMM Michelle FRENCH Nikki SERLENGA Sara WHALEN Shannon MACMILLAN Siri MULLINIX Tiffeny MILBRETT Brandi CHASTAIN Briana SCURRY Carin GABARRA Carla OVERBECK Cindy PARLOW Joy FAWCETT Julie FOUDY Kristine LILLY Atlanta 1996 Gold football 5 (4 1 0) 13 Mary HARVEY Mia HAMM Michelle AKERS Shannon MACMILLAN Staci WILSON Tiffany ROBERTS Tiffeny MILBRETT Tisha VENTURINI Alexander CUDMORE Charles Albert BARTLIFF Charles James JANUARY John Hartnett JANUARY Joseph LYDON St Louis 1904 Louis John MENGES Silver football 3 pts Oscar B. BROCKMEYER Peter Joseph RATICAN Raymond E. LAWLER Thomas Thurston JANUARY Warren G. BRITTINGHAM - JOHNSON Claude Stanley JAMESON www.downloadexcelfiles.com Cormic F. COSTGROVE DIERKES Frank FROST George Edwin COOKE St Louis 1904 Bronze football 1 pts Harry TATE Henry Wood JAMESON Joseph J. -

What Employers Should Consider About the Women Soccer Players' Wage Discrimination Claim

04.07.16 What Employers Should Consider about the Women Soccer Players' Wage Discrimination Claim What would you say if you were paid less money for winning than someone else was paid just for showing up? Is that wage discrimination? Yes it is, according to the stars of U.S. Women's National Soccer Team. Last week, five stars of World Cup Champion women's team filed a wage discrimination claim with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) against U.S. Soccer. Hope Solo, Carli Lloyd, Becky Sauerbrunn, Alex Morgan and Megan Rapinoe claim that despite winning more, they are paid less than the men. According to the complaint: − The women's yearly salary is $72,000, compared to the men's yearly salary of $100,000 − The women are paid less for winning exhibition games than men get for simply showing up. The base pay for women to play in exhibition games is $3,600 and they get a bonus of $1,350 if they win; compared to the men who get paid a base of $5,000, with a bonus of $8,166 if they win; − The women receive a lower per diem rate for daily travel expenses. The women receive $50 per day for domestic travel and $60 per day for international travel, whereas the men receive $62.50 and $75.00 respectively; and − "The pay structure for advancement through the rounds of World Cup was so skewed that, in 2015, the men earned $9 million for losing in the round of 16, while the women earned only $2 million for winning the entire tournament. -

Frauen-Bundesliga Extra • Schutzgebühr 1.- €

OFFIZIELLES MAGAZIN DES DEUTSCHEN FUSSBALL-BUNDES • FRAUEN-BUNDESLIGA EXTRA • SCHUTZGEBÜHR 1.- € Frauen-Bundesliga www.dfb.de www.fussball.de all passion facebook.com/adidasfootball Liebe Freunde des Fußballs, die FIFA Frauen-Weltmeisterschaft 2011 hat dem Frauenfußball in Deutschland eine enorme Aufmerksamkeit gebracht. 782.000 Zuschauer haben die Spiele live in den Stadien verfolgt, zudem haben das Fernsehen, der Hörfunk und die Presse umfangreich über das Turnier berichtet. Allein die wunderbaren TV-Einschaltquoten dokumentieren, mit welchem Interesse das Thema verfolgt wurde. All dies spiegelt eine sensationelle Rückmeldung für unseren Sport wider, aus der jeder, der sich in der Frauen-Bundesliga engagiert, neue Motivation für die Zukunft ziehen kann. Denn mit dem Start der Frauen-Bundesliga in die Saison 2011/2012 bietet sich die nächste Möglichkeit, den Frauenfußball von seiner schönsten Seite zu präsentieren. Schließlich steht diese Spielklasse für hochwertigen und attraktiven Sport. Auch wenn es der DFB- Auswahl nicht gelungen ist, den Traum vom dritten WM-Titelgewinn in Folge zu ver - wirklichen, bleibt die Bundesliga die Liga der Weltmeisterinnen. Nicht nur weil weiterhin viele Spielerinnen aktiv sind, die zu den WM-Triumphen 2003 und 2007 beigetragen haben, sondern auch weil in Saki Kamagui, Yuki Nagasato und Kozue Ando mittlerweile drei japanische Weltmeisterinnen ihre fußballerische Heimat in Deutschland gefun - den haben. Ihre Wechsel zu den Klubs der Frauen-Bundesliga sprechen für das Ansehen und die Leistungsstärke unserer Vereine. Das wird natürlich insbesondere durch die Vergleiche auf internationaler Ebene dokumentiert. Die Erfolge der deutschen Vertreter in der UEFA Women’s Champions League sind ein starkes Argument. In den zehn Jahren seit Bestehen des Wettbewerbs standen deutsche Klubs acht Mal im Endspiel und konnten sechs Mal den Titel gewinnen.