Atlanta Trap and the Current Directions of Afrofuturism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of the Timberland Corporation Jesse Levin

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1998 Transforming corporations to transform society : a case study of the Timberland Corporation Jesse Levin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Levin, Jesse, "Transforming corporations to transform society : a case study of the Timberland Corporation" (1998). Honors Theses. 1259. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1259 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. j UNIVERSITYOF RICHMOND LIBRARIES i 111111111~1mn~~~,~~m1rrn11 Transforming Corporations to Transform Society: A Case Study of the Timberland Corporation By Jesse Levin Jessica Horan Senior Project Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia May,1998 Transforming Corporations to Transform Society: A Case Study of The Timberland Corporation By Jesse Levin Jessica Horan Senior Project Jepson School of Leadership Studies University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia May 1998 Table of Contents I. Introduction 2 II. Literature Review 5 Historical Perspective 6 Economic Perspective 9 The Emergence of Social Enterprise 12 The Timberland Example 17 A Framework for Social Enterprise 18 III. Methodology 23 Limitations 30 IV. Results 33 Sample Group 36 Question 1. 37 Does Timberland's approach to capacity building facilitate multiple levels of transformation? If so, how? Question 2. 40 If Timberland effects internal transformation, does this change the external environment? If so, how? Question 3. -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

The Birdman of Colby: Eagle-Eyed Professor Herb Wilson Is Winging His Way Into the Hearts of Students and Birders Alike

Colby Magazine Volume 89 Issue 2 Spring 2000 Article 9 April 2000 The Birdman of Colby: Eagle-eyed Professor Herb Wilson is winging his way into the hearts of students and birders alike Robert Gillespie Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Gillespie, Robert (2000) "The Birdman of Colby: Eagle-eyed Professor Herb Wilson is winging his way into the hearts of students and birders alike," Colby Magazine: Vol. 89 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol89/iss2/9 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. The Birdman of Colby Eagle-eyed Professor Herb Wilson is winging his way into the hearts of students and birders alike By Robert Gillespie man studying turkey vultures lies next to a dead calf in the to learn how birds in the wild will respond to the made-up sound. A de ert for days, waiting fo r the birds to land on him. Is thi Maybe different syllables mean different thing , he says, or it scientific research, asks a newspaper reporter in an e-mail that may be the song itself that's important and not the individual reaches Colby's resident bird expert, or nutty obse ion? yllables in a particular order. Or certain bird "might hold a "He isn't going to have any success until he gives off ethyl syllable longer; they might drawl; they might have a different mercaptan-that's the smelly stuff, sulfur and mercury in one," pitch," he explained, making the birds sound like plain folk who Herb Wilson answered with amiable matter-of-factness-ex understand each other despite different regional dialects. -

Khalid Releases “Otw” Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign & 6Lack Today—Click Here to Listen Khalid Nominated for Five 2018 Billboard

KHALID RELEASES “OTW” FEAT. TY DOLLA $IGN & 6LACK TODAY—CLICK HERE TO LISTEN KHALID NOMINATED FOR FIVE 2018 BILLBOARD MUSIC AWARDS (Los Angeles, CA)—Today, Multi-platinum global superstar Khalid releases a brand-new track entitled “OTW” featuring Ty Dolla $ign and 6lack. The song is available now at all digital retail providers via Right Hand Music Group/RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. This past Tuesday, Khalid appeared on the Today Show (Click HERE) to announce the 2018 Billboard Music Award nominations for which he has been nominated for five awards including Top New Artist, Top R&B Artist, Top R&B Male Artist, Top R&B Album for American Teen, and Top R&B Song for “Young Dumb & Broke.” Khalid’s most recent release “Love Lies” with Keep Cool/RCA Records’ Normani is off to an explosive start having debuted at #43 on the Billboard Hot 100 and it has already received over 200 million streams worldwide since its release on February 14th. The track, which was just certified GOLD by the RIAA, is garnering critical acclaim with MTV calling it “a match made in musical heaven” and The FADER calling it a “slow-burning R&B ballad”. Since its release, the track has racked up over 150 million streams on Spotify alone, and the song’s official video has over 30 million views on YouTube. “Love Lies” also broke the Top 5 on the streaming platform’s US (#2) and Global (#3) Viral Charts. Additionally, Khalid he will be hitting the road again on “The Roxy Tour”, which will be making a number of stops in major cities including Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Philadelphia. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

Milli-Q Gradient and Milli-Q Gradient A10 User Manual

Milli-Q® Gradient and Milli-Q® Gradient A10® User Manual Notice The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Millipore Corporation. Millipore Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that might appear in this document. This manual is believed to be complete and accurate at the time of publication. In no event shall Millipore Corporation be liable for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising from the use of this manual. We manufacture and sell water purification systems designed to produce pure or ultrapure water with specific characteristics (μS/cm, T, TOC, CFU/ml, Eu/ml) when it leaves the water purification system provided that the Elix Systems are fed with water quality within specifications, and properly maintained as required by the supplier. We do not warrant these systems for any specific applications. It is up to the end user to determine if the quality of the water produced by our systems matches his expectations, fits with norms/legal requirements and to bear responsibility resulting from the usage of the water. Millipore’s Standard Warranty Millipore Corporation (“Millipore”) warrants its products will meet their applicable published specifications when used in accordance with their applicable instructions for a period of one year from shipment of the products. MILLIPORE MAKES NO OTHER WARRANTY, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED. THERE IS NO WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. The warranty provided herein and the data, specifications and descriptions of Millipore products appearing in Millipore’s published catalogues and product literature may not be altered except by express written agreement signed by an officer of Millipore. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

User Manual Milli-Q Integral 3/5/10/15 Systems

User Manual Milli-Q Integral 3/5/10/15 Systems About this User Manual Purpose x This User Manual is intended for use with a Milli-Q® Integral Water Purification System. x This User Manual is a guide for use during the installation, normal operation and maintenance of a Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System. It is highly recommended to completely read this manual and to fully comprehend its contents before attempting installation, normal operation or maintenance of the Water Purification System. x If this User Manual is not the correct one for your Water Purification System, then please contact Millipore. Terminology The term “Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System” is replaced by the term “Milli-Q System” for the remainder of this User Manual unless otherwise noted. Document Rev. 0, 05/2008 About Millipore Telephone See the business card(s) on the inside cover of the User Manual binder. Internet Site www.millipore.com/bioscience Address Manufacturing Millipore SAS Site 67120 Molsheim FRANCE 2 Legal Information Notice The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Millipore Corporation. Millipore Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that might appear in this document. This manual is believed to be complete and accurate at the time of publication. In no event shall Millipore Corporation be liable for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising from the use of this manual. We manufacture and sell water purification systems designed to produce pure or ultrapure water with specific characteristics (PS/cm, T, TOC, CFU/ml, Eu/ml) when it leaves the water purification system provided that the System is fed with water quality within specifications, and properly maintained as required by the supplier. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

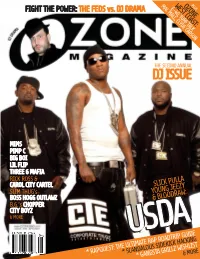

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

Dade County Radio December 2012 Playlist

# No Title Artist Length Count 1 Miami Bass FEST III CHICO 1:18 228 2 FreddieMcGregor_Da1Drop 0:07 126 3 dadecountyradio_kendrick DROP 0:05 121 4 DROP 0:20 104 5 daoneradiodrop 0:22 90 6 Black Jesus @thegame 4:52 52 7 In The End (new 2013) @MoneyRod305 ft @LeoBre 3:53 49 8 M.I.A. Feat. @Wale (Dirty) @1Omarion 3:57 48 9 Up (Remix) K Kutta , LoveRance, 50 Cent 2:43 47 10 Drop-DadeCounty Patrice 0:10 47 11 My Hood (Feat Mannie Fresh) B.G. 3:58 46 12 SCOOBY DOO JT MONEY 4:32 45 13 Stay High _Official Music Video_ Fweago Squad (Rob Flamez) Feat Stikkmann 3:58 45 14 They Got Us (Prod. By Big K.R.I.T.) Big K.R.I.T. 3:27 44 15 You Da One Rihanna 3:22 44 16 Love Me Or Not (Radio Version) @MoneyRod305 Ft @Casely 4:04 44 17 Haters Ball Greeezy 3:14 44 18 Playa A** S*** J.T. Money 4:35 44 19 Ni**as In Paris Jay-Z & Kanye West 3:39 43 20 Myself Bad Guy 3:26 43 21 Jook with me (dirty) Ballgreezy 3:46 42 22 Ro_&_Pat_Black_-_Soldier 05_Ridah_Redd_feat._Z 3:37 42 23 Go @JimmyDade 3:49 42 24 Keepa @Fellaonyac 4:43 41 25 Gunplay-Pop Dat Freestyle Gunplay 1:47 41 26 I Need That Nipsey Hussle ft Dom Kennedy 2:47 40 27 Harsh Styles P 4:18 40 28 American Dreamin' Jay-Z 4:48 40 29 Tears Of Joy (Ft.