Breeding Strategies with Outcross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animals Asia Foundation Dog Breeding - Position Paper

Animals Asia Foundation Dog Breeding - Position Paper February 2010 1 Dog Breeding - Position Paper Feb 2010: Each year across the world many millions of unowned and unwanted dogs are destroyed due to irresponsible dog breeders and owners. Animals Asia supports the de- sexing of all dogs and cats to reduce the number of unwanted companion animals and also supports the adoption of unowned dogs and cats. We are against the breeding and sale of dogs and cats from dog breeders and pet shops. Animals Asia is particularly opposed to individuals operating so-called ‘puppy farms’, where dogs are bred in appalling conditions purely for profit with a total disregard for the health and welfare of both the adult dogs and puppies. Adult bitches are kept in small pens with little or no access to daylight, no social contact with other dogs or other humans and no space to exercise or play. They are bred continuously until they become too old and are then discarded. Puppies bred under such intensive conditions often suffer from genetic abnormalities and other health-related issues. Puppies are frequently removed from their mothers when they are too young, leading to further potential health and behavioural issues. Puppies bred in such intensive conditions are often sold through newspaper adverts, via the internet, at pet shops or in pet superstores. The general promotion of purebred dogs and the desire to breed animals for specific physical and behavioural traits by many dog breeders has lead to significant health and welfare problems in many breeds. In addition to this the emphasis on pure breeds can cause or exacerbate disrespect for mixed breed animals within a community. -

Animal Welfare

57227 Rules and Regulations Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 181 Wednesday, September 18, 2013 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER and be exempt from the licensing and requirements and sets forth institutional contains regulatory documents having general inspection requirements if he or she responsibilities for regulated parties; applicability and legal effect, most of which sells only the offspring of those animals and part 3 contains specifications for are keyed to and codified in the Code of born and raised on his or her premises, the humane handling, care, treatment, Federal Regulations, which is published under for pets or exhibition. This exemption and transportation of animals covered 50 titles pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 1510. applies regardless of whether those by the AWA. The Code of Federal Regulations is sold by animals are sold at retail or wholesale. Part 2 requires most dealers to be the Superintendent of Documents. Prices of These actions are necessary so that all licensed by APHIS; classes of new books are listed in the first FEDERAL animals sold at retail for use as pets are individuals who are exempt from such REGISTER issue of each week. monitored for their health and humane licensing are listed in paragraph (a)(3) of treatment. § 2.1. DATES: Effective Date: November 18, Since the AWA regulations were DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE 2013. issued, most retailers of pet animals have been exempt from licensing by FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Dr. virtue of our considering them to be Service Gerald Rushin, Veterinary Medical ‘‘retail pet stores’’ as defined in § 1.1 of Officer, Animal Care, APHIS, 4700 River the AWA regulations. -

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

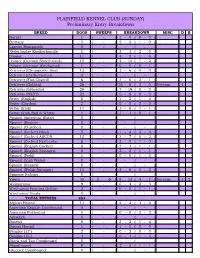

PLAINFIELD KENNEL CLUB (SUNDAY) Preliminary Entry Breakdown

PLAINFIELD KENNEL CLUB (SUNDAY) Preliminary Entry Breakdown BREED DOGS SWEEPS BREAKDOWN MISC D B Barbet 1 ( - ) 1 - 0 ( 0 - 0 ) Brittany 5 ( - ) 2 - 2 ( 1 - 0 ) Lagotto Romagnolo 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Nederlandse Kooikerhondje 5 ( - ) 2 - 1 ( 2 - 0 ) Pointer 11 ( - ) 4 - 2 ( 1 - 4 ) Pointer (German Shorthaired) 15 ( - ) 2 - 10 ( 1 - 2 ) Pointer (German Wirehaired) 1 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 0 - 1 ) Retriever (Chesapeake Bay) 12 ( - ) 2 - 6 ( 4 - 0 ) Retriever (Curly-Coated) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Retriever (Flat-Coated) 6 ( - ) 3 - 0 ( 2 - 1 ) Retriever (Golden) 26 ( - ) 16 - 6 ( 3 - 0 ) Veteran 1 Retriever (Labrador) 28 ( - ) 7 - 19 ( 0 - 2 ) Retriever (NSDT) 23 ( - ) 5 - 9 ( 9 - 0 ) Setter (English) 8 ( - ) 1 - 2 ( 1 - 4 ) Setter (Gordon) 2 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 2 - 0 ) Setter (Irish) 14 ( - ) 3 - 6 ( 4 - 1 ) Setter (Irish Red & White) 3 ( - ) 1 - 1 ( 0 - 1 ) Spaniel (American Water) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Boykin) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Clumber) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Cocker) Black 5 ( - ) 1 - 2 ( 2 - 0 ) Spaniel (Cocker) ASCOB 12 ( - ) 3 - 7 ( 0 - 2 ) Spaniel (Cocker) Parti-color 8 ( - ) 2 - 5 ( 1 - 0 ) Spaniel (English Cocker) 8 ( - ) 3 - 3 ( 1 - 1 ) Spaniel (English Springer) 6 ( - ) 2 - 2 ( 1 - 1 ) Spaniel (Field) 1 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 1 - 0 ) Spaniel (Irish Water) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Sussex) 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Spaniel (Welsh Springer) 15 ( - ) 2 - 6 ( 5 - 2 ) Spinone Italiano 0 ( - ) - ( - ) Vizsla 35 ( 5 - 6 ) 8 - 13 ( 4 - 7 ) Veteran 1 2 Weimaraner 9 ( - ) 0 - 4 ( 2 - 3 ) Wirehaired Pointing Griffon 2 ( - ) 0 - 0 ( 1 - 1 ) Wirehaired Vizsla 0 ( - ) - ( - -

Purebred Dog Breeds Into the Twenty-First Century: Achieving Genetic Health for Our Dogs

Purebred Dog Breeds into the Twenty-First Century: Achieving Genetic Health for Our Dogs BY JEFFREY BRAGG WHAT IS A CANINE BREED? What is a breed? To put the question more precisely, what are the necessary conditions that enable us to say with conviction, "this group of animals constitutes a distinct breed?" In the cynological world, three separate approaches combine to constitute canine breeds. Dogs are distinguished first by ancestry , all of the individuals descending from a particular founder group (and only from that group) being designated as a breed. Next they are distinguished by purpose or utility, some breeds existing for the purpose of hunting particular kinds of game,others for the performance of particular tasks in cooperation with their human masters, while yet others owe their existence simply to humankind's desire for animal companionship. Finally dogs are distinguished by typology , breed standards (whether written or unwritten) being used to describe and to recognize dogs of specific size, physical build, general appearance, shape of head, style of ears and tail, etc., which are said to be of the same breed owing to their similarity in the foregoing respects. The preceding statements are both obvious and known to all breeders and fanciers of the canine species. Nevertheless a correct and full understanding of these simple truisms is vital to the proper functioning of the entire canine fancy and to the health and well being of the animals which are the object of that fancy. It is my purpose in this brief to elucidate the interrelationship of the above three approaches, to demonstrate how distortions and misunderstandings of that interrelationship now threaten the health of all of our dogs and the very existence of the various canine breeds, and to propose reforms which will restore both balanced breed identity and genetic health to CKC breeds. -

The Kennel Club Breed Health Improvement Strategy: a Step-By-Step Guide Improvement Strategy Improvement

BREED HEALTH THE KENNEL CLUB BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY WWW.THEKENNELCLUB.ORG.UK/DOGHEALTH BREED HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY: A STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE 2 Welcome WELCOME TO YOUR HEALTH IMPROVEMENT STRATEGY TOOLKIT This collection of toolkits is a resource intended to help Breed Health Coordinators maintain, develop and promote the health of their breed.. The Kennel Club recognise that Breed Health Coordinators are enthusiastic and motivated about canine health, but may not have the specialist knowledge or tools required to carry out some tasks. We hope these toolkits will be a good resource for current Breed Health Coordinators, and help individuals, who are new to the role, make a positive start. By using these toolkits, Breed Health Coordinators can expect to: • Accelerate the pace of improvement and depth of understanding of the health of their breed • Develop a step-by-step approach for creating a health plan • Implement a health survey to collect health information and to monitor progress The initial tool kit is divided into two sections, a Health Strategy Guide and a Breed Health Survey Toolkit. The Health Strategy Guide is a practical approach to developing, assessing, and monitoring a health plan specific to your breed. Every breed can benefit from a Health Improvement Strategy as a way to prevent health issues from developing, tackle a problem if it does arise, and assess the good practices already being undertaken. The Breed Health Survey Toolkit is a step by step guide to developing the right surveys for your breed. By carrying out good health surveys, you will be able to provide the evidence of how healthy your breed is and which areas, if any, require improvement. -

Pedigree Analysis and Optimisation of the Breeding Programme of the Markiesje and the Stabyhoun

Pedigree analysis and optimisation of the breeding programme of the Markiesje and the Stabyhoun Aiming to improve health and welfare and maintain genetic diversity Harmen Doekes REG.NR.: 920809186050 Major thesis Animal Breeding and Genetics (ABG-80436) January, 2016 Supervisors/examiners: Piter Bijma - Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre, Wageningen University Kor Oldenbroek - Centre for Genetic Resources the Netherlands (CGN), Wageningen UR Jack Windig - Animal Breeding & Genomics Centre, Wageningen UR Livestock Research Thesis: Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre Pedigree analysis and optimisation of the breeding programme of the Markiesje and the Stabyhoun Aiming to improve health and welfare and maintain genetic diversity Harmen Doekes REG.NR.: 920809186050 Major thesis Animal Breeding and Genetics (ABG-80436) January, 2016 Supervisors: Kor Oldenbroek - Centre for Genetic Resources the Netherlands (CGN), Wageningen UR Jack Windig - Animal Breeding & Genomics Centre, Wageningen UR Livestock Research Examiners: Piter Bijma - Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre, Wageningen University Kor Oldenbroek - Centre for Genetic Resources the Netherlands (CGN), Wageningen UR Commissioned by: Nederlandse Markiesjes Vereniging Nederlandse Vereniging voor Stabij- en Wetterhounen Preface This major thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Animal Sciences of Wageningen University, the Netherlands. It comprises an unpublished study on the genetic status of two Dutch dog breeds, the Markiesje and the Stabyhoun. that was commissioned by the Breed Clubs of the breeds, the ‘Nederlandse Markiesjes Vereniging’ and the ‘Nederlandse Vereniging voor Stabij- en Wetterhounen’. It was written for readers with limited pre-knowledge. Although the thesis focusses on two breeds, it addresses issues that are found in many dog breeds. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

(HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association (HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013 Puppy mills are large-scale canine commercial breeding establishments (CBEs) where puppies are produced in large numbers and dogs are kept in inhumane conditions for commercial sale. That is, the dog breeding facility keeps so many dogs that the needs of the breeding dogs and puppies are not met sufficiently to provide a reasonably decent quality of life for all of the animals. Although the conditions in CBEs vary widely in quality, puppy mills are typically operated with an emphasis on profits over animal welfare and the dogs often live in substandard conditions, housed for their entire reproductive lives in cages or runs, provided little to no positive human interaction or other forms of environmental enrichment, and minimal to no veterinary care. This report reviews the following: • What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? • How are Puppies from Puppy Mills Sold? • How Many Puppies Come from Puppy Mills? • Mill Environment Impact on Dog Health • Common Ailments of Puppies from Puppy Mills • Impact of Resale Process on Puppy Health • How Puppy Buyers are Affected • Impact on Animal Shelters and Other Organizations • Conclusion • References What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? Emphasis on Quantity not Quality Puppy mills focus on quantity rather than quality. That is, they concentrate on producing as many puppies as possible to maximize profits, impacting the quality of the puppies that are produced. This leads to extreme overcrowding, with some CBEs housing 1,000+ dogs (often referred to as “mega mills”). When dogs live in overcrowded conditions, diseases spread easily. -

Livestock Department Premium Book

State of Illinois JB Pritzker, Governor Department of Agriculture Jerry Costello II, Director 2021 Illinois State Fair Livestock Department Premium Book DIVISION I LIVESTOCK DEPARTMENT PREMIUM BOOK OF THE 168th YEAR OF ILLINOIS STATE FAIR AUGUST 12-22, 2021 DIVISION I - LIVESTOCK DEPARTMENT PREMIUM BOOK DIVISION II - GENERAL PREMIUM BOOK DIVISION III - GENERAL 4-H PROJECTS DIVISION IV - NON-SOCIETY HORSE SHOWS PREMIUM BOOK DIVISION V - SOCIETY HORSE SHOW PREMIUM BOOK DIVISION VI - SPECIAL EVENTS PREMIUM BOOK JB PRITZKER GOVERNOR JERRY COSTELLO II DIRECTOR KEVIN GORDON MANAGER Printed by Authority of the State of Illinois #21-269/05-25/400 copies 1 Welcome to the 2021 Illinois Sta te Fa ir! Whether you’re joining us in Springfield or in Du Quoin, our state fairs bring together residents and visitors alike, to celebrate all that Illinois has to offer when we stand together – an all-the- more important mission this year. Illinois’ proud agricultural tradition has long been the force that drives our state forward, and the last 18 months have been no different. In March of 2020, when the world seemed to come to a halt, our state’s number one industry kept right on going. After all, there were still crops and animals to care for, deliveries to make, and people to feed. So, even in the face of a global pandemic, Illinois’ farmers, small businesses and commodity groups all came together to keep our food chain secure, a true testament to the vibrancy of the sector. And because no industry was immune to the pains of the last year, the Pritzker administration directed $5 million to help with livestock losses and other costs through our Business Interruption Grant program. -

Is This the Breed for You?

Alaskan Malamute Club Victoria Inc. Incorporations Registered No. A0016353X ALASKAN MALAMUTE About the Alaskan Malamute Club ..................................... Page 2 Information Pack Owning an Alaskan Malamute ............................................. Page 3 Malamute FAQs ..................................................................... Page 4 Personality of the Alaskan Malamute ................................... Page 5 Is this the Breed for You? ....................................................... Page 6 Activities for the Alaskan Malamute ..................................... Page 8 Obedience and your Malamute ........................................ Page 10 Health Problems in the Alaskan Malamute ......................... Page 11 Hip Dysplasia ........................................................................ Page 12 What makes a Breeder Professional? ................................. Page 13 Facts About Breeding .......................................................... Page 13 Selecting an Alaskan Malamute Puppy ............................ Page 14 Breeding your Malamute ..................................................... Page 16 Selecting a Breeder .............................................................. Page 17 Alaskan Malamute Breed Standard ................................... Page 18 AMCV Code of Ethics ........................................................... Page 19 AMCV Statement of Purposes ............................................ Page 19 Breeders Directory & Puppy Register ................................. -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present.