Discovering Old Huddersfield: Part 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oakland Drive, Dalton, Huddersfield, HD5 8PR

Oakland Drive, Dalton, Huddersfield, HD5 8PR Oakland Drive, Dalton, Huddersfield, HD5 8PR Asking Price: £169,500 This well presented semi detached property with driveway providing off road parking is perfect for a small family. Boasting three bedrooms, gardens. Converted garage. The property offers gardens to the front and rear with lawned area. Situated in this very popular residential area, Dalton is approximately one mile east of the town centre between Moldgreen and Kirkheaton. Dalton is located in a small valley surrounded by farmland, but having good access and transport links to Huddersfield Town Centre and motorway network to M62 Leeds and Manchester. The property briefly comprises of Entrance hall, Lounge, Dining Room, and Kitchen on the ground floor. The garage has been converted to make what is currently used as a music room and utility room. On the first floor you will find two double bedrooms, a single bedroom and the family bathroom. Outside to the front is a driveway for off street parking, and a lawned garden. To the rear is again a lawned garden, separate patio area and shed. Viewing is highly recommended to see the what is on offer with this property. ENERGY PERFORMANCE CERTIFICATE The energy efficiency rating is a measure of the overall efficiency of a home. The higher the rating the more energy efficient the home is and the lower the fuel bills will be. Hunters 44 John William Street, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, HD1 1ER | 01484 513777 [email protected] | www.hunters.com VAT Reg. No 205 5252 41 | Registered -

Newsletter No. 74 Autumn 2008 Editorial

NEWSLETTER NO. 74 AUTUMN 2008 EDITORIAL Welcome to the latest Newsletter; I hope you have had an enjoyable summer in spite of the dreadful weather, Due to a clash of dates I was unable to attend this year’s AIA Conference which was held in Wiltshire and I look forward to reading the report which will appear in Industrial Archaeology News. I am also looking forward to the forthcoming 2008-2009 Lecture Programme; full details are given on the separate sheet, meeting as usual on Saturday mornings at Claremont. In the past the Section has considered whether midweek evening meetings or Saturday afternoons would attract more members to join and attend but the general view from those who have expressed it, is that Saturday mornings are preferred. However please note that the 2009 AGM will be starting earlier at 10.30am. This is because we will have another local walk in the afternoon starting at 2pm and starting the AGM half an hour earlier gives a little more time for members’ contributions and lunch. I am sure that you will agree with me that our Lecture Secretary, Jane Ellis, has yet again organised an interesting and varied programme and I hope many of you will be able to attend at least a few lectures during the season. Robert Vickers will also lead a walk around Huddersfield on Sunday 10 May 2009, meeting at the Railway Station at 11am with a pub lunch. Let’s hope there is better weather for this than his walk around Bradford, which is reported on later in the Newsletter. -

Please Register As a Carer at Your GP Practice Now!

Carers really do count! Winter/Spring 2020 Newsletter Celebrating Carers in 2019 Carers Count held two carers celebration events this year. One was at Brian Jackson House in Huddersfield and the other was at Crow Nest Park in Dewsbury. Both events were well attended by carers and their loved ones and were a great day out for all. Both events provided food and entertainment. The activities included head massages donated by the White Rose Beauty College, Bollywood dancing from Salma Zaman and MMO Movement and Dance with Kirklees Council, to name a few. Food was provided by Cake Box in Dewsbury and Frankie’s Burgers in Batley and there were many raffle and tombola prizes donated from a number of organisations. “I would like to thank you all so “It was most enjoyable, it takes you “I’ve had fun and an absolutely much for all you do and for this out of your problems and gets you fantastic time! A thousand thanks.” lovely birthday celebration. It has thinking about other things. The been so much fun. You are all staff are all nice and helpful.” greatly appreciated.” Who are Carers Count? Carers Count works in the Kirklees area with carers over the age of 18 who look after either an adult over the age of 18 or a child with an additional need. It is a free, independent support service. This service is provided by Cloverleaf Advocacy. Contact us on 0300 012 0231 or email [email protected] Service Managers Steph, Heather and Rachael manage the Carers Count service in Kirklees across the Huddersfield and Dewsbury sites. -

Skelmanthorpe and District U3A a HISTORY of EDUCATION in THE

Skelmanthorpe and District U3A A HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN THE DISTRICT SEPTEMBER 2018 1 CONTENTS 1. Education Time line 2. Introduction 3. Education in the Upper Dearne Valley 4. Schools in Skelmanthorpe - “The Old Town School” - “Dame” schools - The National School - The Board School - Skelmanthorpe School Board - Methodist schools in Skelmanthorpe 5. Sunday Schools 6. Libraries 7. Schools in other villages - Kirkburton - Emley - High Hoyland and Clayton West - Cumberworth - Denby Dale 8. Education and the Society of Friends 9. Adult Education - Adult schools - Mechanics Institutes - Mutual Improvement Societies 10. Sir Percy Jackson APPENDICES 1. Original Sources and Extracts from Newspapers 2. Education of Women - Huddersfield Female Educational Institute 2 1. Education Time Line Pre-1700 Schools associated with some churches and monasteries 1700s Endowed charity schools for the poor Schools established by richer inhabitants by subscription: “Old Town Schools”, e.g. Kirkburton, Skelmanthorpe, Deneby High Flatts boarding school established by Society of Friends. 1800 Methodist schools started. Sunday Schools started. e.g. Wesleyan School, Skelmanthorpe. Enclosure Acts provided funding for charity schools, e.g. Skelmanthorpe Manor Inclosure Act, 1800 Dame” schools began. 1802 Peel’s Factory Act encouraged “education for the labouring class”. 1807 Parochial Schools Bill made provision for education of “labouring classes”. 1811 National Society started - CofE organisation aimed to provide a school in every parish. 1814 British and Foreign Schools Society started founded by “liberals” as alternative to National Society. British School started in Emley. 1820s National Schools in Skelmanthorpe, Kirkburton and other villages. 1832 Representation of the People Act 1833 First government grant of £20,000 for education. -

2006 Yorkshire

Top 20 Paid Attractions- Yorkshire Local Authority Adult Child County in which District in which Visitors Visitors Estimate/ % Change 06- Admission Admission Name of Attraction attraction located attraction is located Category 2005 2006 Exact 05 Charge Charge 1 Flamingo Land Theme Park & Zoo North Yorkshire RYEDALE leisure/theme park 1400210 1302195 estimate -7 £19.00 £19.00 2 York Minster UA York place of worship 803000 895000 estimate 11 £9.00 £0.00 3 Fountains Abbey & Studley Royal North Yorkshire HARROGATE historic house 312000 313388 exact 0 £6.50 £3.25 4 Eureka! Museum for Children West Yorkshire CALDERDALE museum/gallery 246195 250364 exact 2 £7.25 £7.25 5 Cannon Hall Open Farm South Yorkshire BARNSLEY farm 250000 250000 estimate 0 £3.25 £2.75 6 Harewood House West Yorkshire LEEDS historic house 302052 221880 exact -27 £11.30 £6.50 7 Castle Howard UA York historic house 188334 203932 exact 8 £9.50 £6.50 8 RHS Garden Harlow Carr North Yorkshire HARROGATE garden 179228 193889 exact 8 £6.00 £1.60 9 Sewerby Hall & Gardens UA East Riding of Yorkshire historic house 160000 175000 exact 9 £3.50 £1.50 10 Magna South Yorkshire ROTHERHAM science/technology 137439 155210 exact 13 £9.95 £7.95 11 Yorkboat UA York other historic 137157 130932 exact -5 £6.50 £3.30 12 Normanby Hall Country Park UA North Lincolnshire historic house 151582 129700 estimate -14 £4.20 £2.10 13 GUIDE FRIDAY LTD THE YORK YORK other historic 126228 125536 exact -1 £8.50 £4.00 14 Clifford's Tower UA York castle/fort 127239 122493 exact -4 £3.00 £1.00 15 Whitby Abbey North -

Engagement Event – December 2020

Engagement event report December 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. Background to the event ................................................................................................ 3 2. Promotion of the event ................................................................................................... 3 3. Attendance at the event ................................................................................................. 4 4. Presentations ................................................................................................................. 4 5. Questions / comments raised ......................................................................................... 4 6. Next steps ...................................................................................................................... 6 Appendix A - Groups / organisations signed up to attend the event ..................................... 7 Appendix B - Groups / organisations that attended the event ............................................... 9 Appendix C – Presentation - accessible version ................................................................. 10 Appendix D – Presentation - PowerPoint version ............................................................... 21 2 1. Background to the event NHS North Kirklees and Greater Huddersfield Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) hold regular events to give the public an opportunity to hear about the work that the CCGs have been doing, our priorities and plans for the future. The last event was held in -

Kirklees CCG Primary Care Commissioning Committee 9.00 Am, Wednesday 28 April 2021 to Be Held As a VIRTUAL Meeting

Kirklees CCG Primary Care Commissioning Committee 9.00 am, Wednesday 28 April 2021 To be held as a VIRTUAL meeting Agenda Members Initials Role Apologies Beth Hewitt (Chair) (BH) Lay Member: Patient and Public Involvement - Hilary Thompson (Vice- (HT ) Lay Member: Finance and Remuneration - Chair) Ian Currell (ICu) Chief Finance Officer - Carol McKenna (CM) Chief Officer - Penny Woodhead (PW) Chief Quality and Nursing Officer - Martin Wright (MW) Lay Member: Audit and Governance - In Attendance Dr Ibrar Ali (IA) Independent Medical Advisor - Stacey Appleyard (SA) Healthwatch Representative - Dr Dil Ashraf (DA) Chair, Council of Members - Dr N Chandra (NC) Local Medical Committee Representative - Laura Ellis (LE) Head of Corporate Governance - Jan Giles (JG) Senior Manager Practice Support and - Development Dawn Ginns (DG) NHSE Representative - Danielle Hodson (DH) Assistant Internal Audit Manager (agenda item - 9) Dr Abid Iqbal (AI) Independent GP Advisor - Dr Bert Jindal (BJ) Local Medical Committee Representative - Diane Lane (DL) Practice Support and Development Manager - (agenda item 10) John Laville (JL) Patient Representative - Dr Yasar Mahmood (YM) GP Member - Dr Steve Ollerton (SO) GP Member - Martin Pursey (MP) Head of Contracting and Procurement - Vacancy Health and Wellbeing Board Representative Catherine Wormstone (CW) Head of Primary Care Strategy and - Commissioning Rob Willis (RW) Head Of Financial Reporting and Accounting - Mahmood Yaqoob (MY) Other Primary Care Professional Practice - Member Primary Care Commissioning Committee Meeting – 28 April 2021 1 Agenda ITEM TIME BY PAGE 1. Welcome, Apologies and Declarations of Interest To open the meeting with introductions; note and record any apologies; 9:00 BH Verbal and declare any interests outside the committee. -

The Boundary Committee for England

THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF KIRKLEES Draft Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the Borough of Kirklees February 2003 Sheet 4 of 11 M 62 Sheet 4 1 "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission 2 with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. 43 A 6 Licence Number: GD03114G" 4 5 6 Upper Cote Farm North Lodge 3 Farm Only Parishes whose Warding has been altered by these Recommendations have been coloured. 7 8 9 10 11 ASHBROW WARD Und Und D Und OA E R US HO IG BR H O L L IN Golf Course S H E Y R O A D Middle Haigh G RIM House Farm ESC 2 AR 6 RO M AD Warren House Farm H a r ro w Wappy Spring Haig House C Farm Hill Farm H lo 3 A u 4 L g 6 I h A F Lower Burn Farm A X D A R O O R A R O D Middle Burn Farm O G M D R Y A I LE O M D R E AD N E S RO LI E SS R C CRO T A RTH W R NO E Y R O A KEY D C OA CH DISTRICT BOUNDARY RD Haig Cross BIRCHENCLIFFE G Farm rim EXISTING DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY (TO BE RETAINED) es ))) ca ))) Braeside Farm Cliffe Farm ))) ))) r ))) )) D EXISTING DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY (NO LONGER TO BE UTILISED) Peat Ponds ike Farm Reap Hurst PROPOSED DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY Farm PARISH BOUNDARY REAP HIRST RD HA LIF AX PARISH WARD BOUNDARY OL D R PW OA PARISH WARD COINCIDENT WITH OTHER BOUNDARIES D PRINCE ROYD PROPOSED WARD NAME ASHBROW WARD Crosland Road Farm Church NORWO EXISTING WARD NAME (TO BE RETAINED) OD ROA GOLCAR WARD B D IRKBY -

Windmill Inn, Skelmanthorpe N-923124

File Ref: N-923124 Windmill Inn 2 Busker Lane, Skelmanthorpe, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD8 9EP Tenure · Free of Tie lease Leasehold · Prominent corner position · Good quality residential area Price · 3 bedroom first floor accom Nil Premium · Good outside spaces Andrew Spencer Associate 0113 234 0304 [email protected] Windmill Inn 2 Busker Lane, Skelmanthorpe, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD8 9EP Google © Copyright (2019). All rights reserved. Location The Windmill is located in the village of Skelmanthorpe on a prominent corner plot. The village is surrounded by a number of other reasonable sizes of population of good quality and is approximately 8 miles south east of the town of Huddersfield and 11 miles south west of the city of Wakefield. Description A detached two storey property with colour washed elevations under a pitched roof with a single storey flat roof extension to the rear. There is a small beer patio area to the front and a car park for approximately 10 cars to the rear. Additionally there is a single garage, an enclosed garden area and a bowling green to the rear. Google © Copyright (2019). All rights reserved. Windmill Inn 2 Busker Lane, Skelmanthorpe, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD8 9EP External There is a beer patio area to the front, parking for approximately 10 cars, a single garage for storage, an enclosed garden and a separate bowling green. Tenure Leasehold: The premises are available by way of a free of tie lease for 20 years on full repairing and insuring terms the guide rent is to be advised per annum with rent reviews on a 5 yearly basis and annual RPI increases. -

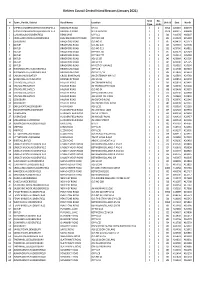

SL Inventory 5 Jan 21 Duplicates Removed.Xlsx

Kirklees Council Central Island Beacons (January 2021) Unit No. # Town , Parish, District Road Name Location Unit Id East North Type Units 1 UPPER CUMBERWORTH,HUDDERSFIELD BARNSLEY ROAD NR 54 C 1 S05A 420687 408779 2 UPPER CUMBERWORTH,HUDDERSFIELD BARNSLEY ROAD NR RESERVOIR C 1 S07A 420915 408698 3 LONGWOOD,HUDDERSFIELD BENN LANE OPP LC1 C 1 S01 410978 416607 4 CROSLAND MOOR,HUDDERSFIELD BLACKMOORFOOT ROAD OPP NO 330 C 1 S06 412224 415290 5 DEWSBURY BRADFORD ROAD O/S NO 50 C 1 S07 424437 422173 6 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD O/S NO 209 C 1 S13 424469 422798 7 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD O/S NO 513 C 1 S31 423796 424811 8 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD OPP NO 747 C 1 S37 423276 425349 9 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD OPP NO 777 C 1 S39 423212 425418 10 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD ADJ LC135 C 1 S40 423099 425505 11 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD ADJ LC150 C 1 S43 422696 425725 12 BATLEY BRADFORD ROAD NR 427 OP GARAGE C 1 S23 424559 424304 13 BIRCHENCLIFFE,HUDDERSFIELD BRIGHOUSE ROAD OPP LC8 C 1 S05 411748 419410 14 BIRCHENCLIFFE,HUDDERSFIELD BRIGHOUSE ROAD OPP LC11/12 C 1 S06 411843 419452 15 CARLINGHOW,BATLEY CROSS BANK ROAD JN CENTENARY WAY CIP C 1 S01 423564 424769 16 GOMERSAL,CLECKHEATON DEWSBURY ROAD ADJ LC216 C 1 S50 420853 426950 17 STAINCLIFFE,BATLEY HALIFAX ROAD JN COMMON ROAD C 1 S61 422819 423491 18 STAINCLIFFE,BATLEY HALIFAX ROAD JN THORNCLIFFE ROAD C 1 S66 423390 423100 19 STAINCLIFFE,BATLEY HALIFAX ROAD O/S NO 34 C 1 S68 423468 423035 20 STAINCLIFFE,BATLEY HALIFAX ROAD OPP LC300 ON C/RES C 1 S70 423536 422968 21 STAINCLIFFE,BATLEY HALIFAX ROAD ADJ LC304 ON C/RES C 1 S72 423660 -

Download Chapter

chapter two 43 The Ramsdens and the Public Realm in Huddersfield, 1671-1920 david griffiths Introduction TO A WELL-INFORMED visitor standing at Huddersfield’s market cross today, a century after the Ramsdens sold their Huddersfield estate, their impact on the townscape remains inescapable. The market cross itself, topped by the family arms, records the grant of market rights to John Ramsden (later the first baronet) in 1671. The four streets which meet there, Kirkgate, Westgate, New St and John William St, were named by the Ramsdens, and the last two were their creation. With New St, dating from about 1770, they initiated a small street grid to the south, dominated by the Ramsden-built Cloth Hall of 1765/6; from there the axis of Cloth Hall St and the early nineteenth century King St ran east to Aspley Basin, the terminal port of Sir John Ramsden’s Canal (1775-80). John William St, named after the fifth baronet, opened up a new Victorian grid to the north, with the Palladian railway station (1846-51) as its dominant feature. To the south of the cross is the handsome Georgian row of the Brick Buildings and to the north Waverley Chambers, one of three Queen Anne style office buildings along Byram St (named after the family seat near Pontefract); all four were built by the Ramsden estate as commercial developments. There is, then, a great deal of surviving evidence that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Huddersfield was a ‘Ramsden town’. Such was certainly the claim of the Ramsden estate at the time. -

Come Walking in and Around Denby Dale

Come walking in and around Denby Dale As well as maps and directions, the leaflets provide information on public transport and local facilities - Come walking in the beautiful countryside and an insight into our area’s heritage. Up-dates on of the Denby Dale district. Discover the the trails can be found at villages of Denby Dale itself; Birdsedge www.denbydale-walkersarewelcome.org.uk from and High Flatts; Clayton West; Upper where the 14 leaflets can also be downloaded. and Lower Cumberworth; Upper and For information on guided walks see Lower Denby; Emley and Emley Moor; www.upperdenby.org.uk/ddpwg and Scissett;and Skelmanthorpe, with their www.penline.co.uk rich and fascinating heritage...and an excellent network of public rights of way. A wide range of visitor information is available at the excellent These 14 accompanying leaflets describe walks www.denbydale-kirkburton.org.uk of varying length covering most of our area.12 We hope local residents and visitors will enjoy the of these are circular walks...3 starting in Denby walks and the amenities the area has to offer. Dale, 3 in Skelmanthorpe, 3 in Emley, 2 in Clayton West and 1 in High Flatts. The 2 linear Please use public transport if at all possible. The routes link Denby Dale station with Shepley and Penistone railway line and the local bus services Penistone stations respectively. provide an excellent means to access the area. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor The areas covered by the walks and their starting points.