Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chirang District

STATE: ASSAM AGRICULTURE CONTINGENCY PLAN: CHIRANG DISTRICT 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro –Climatic Region (Planning Commission) Eastern Himalayan Region Agro- Climatic/ Ecological Zone Lower Brahmaputra Valley Zone, Assam Agro Ecological Sub Region (ICAR) Assam & Bengal Plain, hot perhumid ecosystem with alluvium derived soils Agro Climatic Zone (NARP)* 011 Lower Brahmaputra Valley Zone List all the districts falling under the NARP Zone Kamrup, Nalbari, Barpeta, Bongaigaon, Baska, Chirang, Kokrajhar, Dhubri, Goalpara Geographic Coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude 26°28' to 26° 54' North 89.42° to 90°06' East 31 m MSL Name and address of the concerned Regional Agricultural Research Station, AAU, Gossaigaon ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRS/RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Chirang, Assam Agricultural University, Kajalgaon -783385 1.2 Rainfall Average (mm) Normal Onset Normal Cessation (specify week and (specify week and month) month) SW monsoon (June-Sep’2013) 1961.4 1st week of June 4th week of September NE Monsoon (Oct-Dec’2013) 171.6 Winter (Jan- Feb’2013) 34.6 Summer (March-May’2014) 670.5 1st week of April 4th week of may Annual 2838.1 Source: http://www.agriassam.in/rainfall/districtwise-rainfall-during-2012.pdf *If a district falls in two NARP zones, mention the zone in which more than 50% area falls 1 1.3 Land use pattern Geographical Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Under Barren and Current Other of the district area area non- pastures wasteland Misc. tree uncultivable fallows fallows (latest statistics) agricultural crops and land use groves Area (000’ ha) 109.0 9.7 7.0 6.8 2.6 1.6 0.5 4.1 0.5 (Source: SREP Chirang district) 1.4 Major Soils Major soil description Total Area (‘000 ha) Percent (%) of total 1. -

Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland By

Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland rishav kumar thakur !"#$$% 128 # Shahpur Jat, 1st &oor %'( )'*+, 110 049 '-$,*: [email protected] ('#.,/': www.zubaanbooks.com Published by Zubaan Publishers Pvt. Ltd 2019 In collaboration with the Sasakawa Peace Foundation fragrance of peace project All rights reserved Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi with a strong academic and general list. It was set up as an imprint of India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and carries forward Kali’s tradition of publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. Zubaan means tongue, voice, language, speech in Hindustani. Zubaan publishes in the areas of the humanities, social sciences, as well as in fiction, general non-fiction, and books for children and young adults under its Young Zubaan imprint. Typeset in Arno Pro 11/13 Tracing the Continuities of Violence in Bodoland INTRODUCTION The Bodoland Territorial Autonomous Districts (BTAD), renamed as Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) in 2020, was created in 2003 as an autonomous region within Assam in response to the long movement for Bodo autonomy. After decades of adopting peaceful means (with sporadic attacks on government property or staff), militant factions of the movement started targeting non-Bodo residents since the late 1980s. Over time, organizations and coalitions have emerged among non-Bodo communities – both recognized as indigenous or as marginalized immigrants such as Adivasis1 and Bengali-speaking Muslims2. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 10, Issue, 07, pp.71469-71478, July, 2018 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE BODOLAND TERRITORIAL COUNCIL A SIXTH SCHEDULE AREA: A MINI VIEW *Ashok Brahma (HOD) Dept. of Political Science, Vice-Principal Upendra National Academy, Kokrajhar, Jury Member of Upendra Nath Brahma Trust (UNBT) ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: In this study evaluate the Bodoland Territorial Council a Sixth Schedule Area and the working of the Received 19th April, 2018 Bodoland Territorial Council the Administrative powers, functions and the Achievements. The Received in revised form Autonomous District Councils or Regional Councils under the Sixth Schedule are looked upon as 06th May, 2018 instruments for welfare of the tribal people and to preserve their own tradition and culture. Accepted 15th June, 2018 Contribution to social, political, economic and cultural development is regarded to be the core Published online 30th July, 2018 strategy of the District Councils or Regional Councils in the North East India. Bodoland Territorial Council is an Autonomous Council within the State of Assam under the Sixth Schedule of the Key words: Constitution of India. It has been formed with the aim to fulfill the long pending aspiration of the Bodos, BTC, Sixth Schedule, area. The Memorandum of Settlement (2003) signed by the three parties- Government of India, Powers, Functions, Government of Assam and Bodo Liberation Tigers explores various aspects on the formation of BTC Development, Tribal. within the State of Assam. Important aspects as reflected in the Memorandum are being discussed. -

LIST of POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION and RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME ZONE CODE Search

LIST OF POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION AND RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME GUW ZONE CODE 70 Search: Commission Commissionerate Code Commissionerate Jurisdiction Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction erate Name Districts of Kamrup (Metro), Kamrup (Rural), Baksa, Kokrajhar, Bongaigon, Chirang, Barapeta, Dhubri, South Salmara- Entire District of Barpeta, Baksa, Nalbari, Mankachar, Nalbari, Goalpara, Morigaon, Kamrup (Rural) and part of Kamrup (Metro) Nagoan, Hojai, East KarbiAnglong, West [Areas under Paltan Bazar PS, Latasil PS, Karbi Anglong, Dima Hasao, Cachar, Panbazar PS, Fatasil Ambari PS, Areas under Panbazar PS, Paltanbazar PS & Hailakandi and Karimganj in the state of Bharalumukh PS, Jalukbari PS, Azara PS & Latasil PS of Kamrup (Metro) District of UQ Guwahati Assam. UQ01 Guwahati-I Gorchuk PS] in the State of Assam UQ0101 I-A Assam Areas under Fatasil Ambari PS, UQ0102 I-B Bharalumukh PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Gorchuk, Jalukbari & Azara PS UQ0103 I-C of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Nagarbera PS, Boko PS, Palashbari PS & Chaygaon PS of Kamrup UQ0104 I-D District Areas under Hajo PS, Kaya PS & Sualkuchi UQ0105 I-E PS of Kamrup District Areas under Baihata PS, Kamalpur PS and UQ0106 I-F Rangiya PS of Kamrup District Areas under entire Nalbari District & Baksa UQ0107 Nalbari District UQ0108 Barpeta Areas under Barpeta District Part of Kamrup (Metro) [other than the areas covered under Guwahati-I Division], Morigaon, Nagaon, Hojai, East Karbi Anglong, West Karbi Anglong District in the Areas under Chandmari & Bhangagarh PS of UQ02 Guwahati-II State of Assam UQ0201 II-A Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Noonmati & Geetanagar PS of UQ0202 II-B Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Pragjyotishpur PS, Satgaon PS UQ0203 II-C & Sasal PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Dispur PS & Hatigaon PS of UQ0204 II-D Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Basistha PS, Sonapur PS & UQ0205 II-E Khetri PS of Kamrup (Metropolitan) District. -

Introduction of the Bodos

Chapter 2 Introduction of the Bodos India is a meeting ground of diverse races, cultures, civilizations, religions, languages, ethnic groups and societies. Streams of different human races like Austro-Asiatic, Negritos, Dravidians, Alpines, Indo-Mongoloids, Tibeto-Burman and Aryans penetrated in India at different periods through different routes .They migrated and settled in different parts of India making their own history, culture and civilization. They had contributed to the structuring of the great Indian culture, history and civilization. The Tibeto-Burman people are predominant in whole North-Eastern region. The Bodos are one of the earliest settlers in Assam. The older generation of scholars used the term 'Bodo' to denote the earliest Indo- Mongoloid migrants to eastern India who subsequently spread over different regions of Bengal, Assam and Tripura. Grierson identifies the Bodos as a section of the Assam-Burma group of the Tibeto-Burman speakers belonging to the Sino-Tibetan speech family.1 S.K. Chatterjee subscribes to the same view. According to him these people migrated to eastern India in the second millennium B.C. and a large portion of them was absorbed within societies of plains-man at quite an early state.2 Isolation caused fragmentation of the original stock and ultimately the branches assumed independent tribal identities like the Tipra, the Bodo-Kachari, the Rabha, the Dimsasa, the Chutiya etc. Rev. Sydney Endle, in his monograph, The Kacharis, used 'The Kachari' in the same wider sense incorporating all these branches. In present day socio-political terminology 'the Bodo' means the plain tribes of the Brahmaputra Valley known earlier as 'the Bodo-Kachari'. -

Initial Environment Examination IND

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 41614-023 November 2017 Part A: Main Report (Pages 1-102) and Annexures IND: Assam Power Sector Enhancement Investment Program - Tranche 1 Submitted by Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, Guwahati This report has been submitted to ADB by the Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, Guwahati and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This report is an updated version of the IEE report posted in August 2009 available on http://www.adb.org/projects/documents/assam-power-sector-enhancement-investment- program-2. This updated initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ASSAM ELECTRICITY GRID CORPORATION LIMITED Loan 2592-IND (Tranche 1) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION TRANSMISSION SYSTEM EXPANSION ASSAM POWER SYSTEM ENHANCEMENT PROJECT GUWHATI NOVEMBER 2017 Assam Electricity Grid Corporation Limited EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 CHAPTER – 1 3 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT 3 1.2 BACKGROUND AND PRESENT SCENARIO -

Language, Part IV B(I)(A)-C-Series, Series-4, Assam

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 04 - ASSAM PART IV B(i)(a) - C-Series LANGUAGE Table C-7 State, Districts, Circles and Towns DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, ASSAM Registrar General of India (tn charge of the Census of India and vital statistics) Office Address: 2-A. Mansingh Road. New Delhi 110011. India Telephone: (91-11) 338 3761 Fax: (91-11) 338 3145 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.censusindia.net Registrar General of India's publications can be purchased from the following: • The Sales Depot (Phone: 338 6583) Office of the Registrar General of India 2-A Mansingh Road New Delhi 110 011, India • Directorates of Census Operations in the capitals of all states and union territories in India • The Controller of Publication Old Secretariat Civil Lines Delhi 110054 • Kitab Mahal State Emporium Complex, Unit No.21 Saba Kharak Singh Marg New Delhi 110 001 • Sales outlets of the Controller of Publication aU over India • Census data available on the floppy disks can be purchased from the following: • Office of the Registrar i3enerai, india Data Processing Division 2nd Floor. 'E' Wing Pushpa Shawan Madangir Road New Delhi 110 062, India Telephone: (91-11) 608 1558 Fax: (91-11) 608 0295 Email: [email protected] o Registrar General of India The contents of this publication may be quoted citing the source clearly PREFACE This volume contains data on language which was collected through the Individual Slip canvassed during 1991 Censlis. Mother tongue is a major social characteristic of a person. The figures of mother tongue were compiled and grouped under the relevant language for presentation in the final table. -

Derecognized

File No.21-2/2019-CZA(Vol.I)(E)-Part(1) Computer No. 153933 Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change CENTRAL ZOO AUTHORITY B-1 Wing, 6th Floor, Pandit Deendayal Antyodaya Bhawan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi – 110 003, Telephone: +91-11-24367846/51/52, E-mail: [email protected] Dated March 31, 2021 To The Chief Wildlife Warden, Department of Environment and Forest, Aranya Bhavan, Panjabari, Guwahati – 781 037, Assam, E-mail: [email protected] Subject: Renewal of recognition of the Bijni Deer Park, Bongaigaon, Assam, under Section 38-H of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972 – regarding Reference: 1. This Office Memorandum F.No.7-10/2020-CZA(PART-I) dated August 25, 2020 2. This Office letter F.No.21-2/2019-CZA(AK)/2039/2020 dated January 6, 2020 3. This Office letter F.No.19-96/92-CZA(26)(M) dated December 8, 2010 4. Application vide letter No.B/SFK/2/31/5/Bijni Park/41(B) dated June 22, 2016 from the DFO, Social Forestry Division, Kokrajhar Sir, With reference to above, the undersigned is directed to inform that recognition of the Bijni Deer Park, Bongaigaon, under Section 38-H of the Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, was valid till December 31, 2012. Application dated June 22, 2016 received in this office from the DFO, Social Forestry Division, Kokrajhar, for renewal of recognition. Shri T. Ajay Kumar, Evaluation and Monitoring Assistant in Office of the CZA deputed by this office has evaluated the zoo on January 29, 2020. -

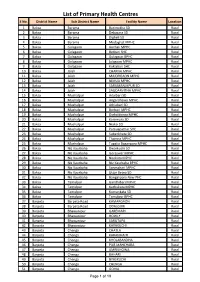

List of Primary Health Centres S No

List of Primary Health Centres S No. District Name Sub District Name Facility Name Location 1 Baksa Barama Barimakha SD Rural 2 Baksa Barama Debasara SD Rural 3 Baksa Barama Digheli SD Rural 4 Baksa Barama Medaghat MPHC Rural 5 Baksa Golagaon Anchali MPHC Rural 6 Baksa Golagaon Betbari SHC Rural 7 Baksa Golagaon Golagaon BPHC Rural 8 Baksa Golagaon Jalagaon MPHC Rural 9 Baksa Golagaon Koklabari SHC Rural 10 Baksa Jalah CHARNA MPHC Rural 11 Baksa Jalah MAJORGAON MPHC Rural 12 Baksa Jalah NIMUA MPHC Rural 13 Baksa Jalah SARUMANLKPUR SD Rural 14 Baksa Jalah SAUDARVITHA MPHC Rural 15 Baksa Mushalpur Adalbari SD Rural 16 Baksa Mushalpur Angardhawa MPHC Rural 17 Baksa Mushalpur Athiabari SD Rural 18 Baksa Mushalpur Borbori MPHC Rural 19 Baksa Mushalpur Dighaldonga MPHC Rural 20 Baksa Mushalpur Karemura SD Rural 21 Baksa Mushalpur Niaksi SD Rural 22 Baksa Mushalpur Pamuapathar SHC Rural 23 Baksa Mushalpur Subankhata SD Rural 24 Baksa Mushalpur Thamna MPHC Rural 25 Baksa Mushalpur Tupalia Baganpara MPHC Rural 26 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Dwarkuchi SD Rural 27 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Goreswar MPHC Rural 28 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Naokata MPHC Rural 29 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Niz Kaurbaha BPHC Rural 30 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Sonmahari MPHC Rural 31 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Uttar Betna SD Rural 32 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Bangalipara New PHC Rural 33 Baksa Tamulpur Gandhibari MPHC Rural 34 Baksa Tamulpur Kachukata MPHC Rural 35 Baksa Tamulpur Kumarikata SD Rural 36 Baksa Tamulpur Tamulpur BPHC Rural 37 Barpeta Barpeta Road KAMARGAON Rural 38 Barpeta Barpeta Road ODALGURI Rural 39 Barpeta -

Assam 1)Kamrup( Rural) District

Assam 1)Kamrup( Rural) district Major observations of Regional Evaluation Team, Kolkata about the Evaluation work in Kamrup (Rural) district of Assam in June, 2010. I. Details of the visited Institutions: District visited BPHCs, RH, PPCs and NGSCs visited visited Kamrup (Rural) BPHC: Uparholi Rajabaha, Maniari Tinali, Amranga Baihat, Tarap FRUs: Suailkuchi, Hajo Losana, Jamtal, Bongshser, Dampur, Bongshore CHC: Mirza Baradadhi, Damdama and Mirza II. Major Observations: 1. Health Human Resources: a. Some posts of medical personnel at the various health centres in the district were reported to be lying vacant i.e. 22 MOs (out of 206 sanctioned), 15 specialist (out of 38 sanctioned). b. Under the category of non-medical, 20 posts (out of 602 sanctioned) of ANM, 2 posts (out of 20 sanctioned) of MPW (M), 5 posts (out of 33 sanctioned) of LHV/HS (F), 19 post (out of 164 sanctioned) of Staff Nurse and 9 posts (out of 73 sanctioned) of Lab Technician were also lying vacant in the various institutions/ centres in the district. 2. Functioning of Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS): a. It was reported that as many as 70 RKS have been constituted and also were functioning in the district but only 3 RKS were registered till the time of visit. It was also reported that the members of RKS meet regularly. b. Funds provided to the RKSs and expenditure incurred were not made available to the team in the district. 3. Functioning of ASHA and VHSC: a. In view of total 991 villages in the district, 1615 ASHAs had been selected in the district and out of them 1523 ASHAs were provided training up to 5th modules. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Criticality of Capital Formation ‘In’ and ‘For’ Agriculture Need Not Be Over Emphasized

PLP 2016-17 Chirang District EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The criticality of capital formation ‘in’ and ‘for’ agriculture need not be over emphasized. However, the recent declining trend in investment credit vis-à-vis crop loan has serious implications for sustaining capital formation. The theme selected for the PLP 2015-16 is “Accelerating the pace of capital formation in agriculture and allied sector”. The PLP maps the potential in priority sectors which could be exploited with institutional credit within a specified time frame. PLP are intended to provide a meaningful direction to the flow of credit to different sectors at the ground level taking into account all relevant factors. The various linkage and other support required to be provided by line departments to facilitate credit flow as planned are also listed in the PLP. CHIRANG district is one of the four districts of Bodoland Territorial Area District (BTAD) under the Government of Assam. It is bounded by the Kingdom of Bhutan on the North, Bongaigaon district on the South, Baksa on the East and Kokrajhar on the West. The district has 2 sub-divisions Kajalgaon sadar and Bijni civil subdivision and 3 blocks – Sidli, Borobazar and Manikpur. The district Head quarters is well connected with other parts of the state. According to the 2011 census Chirang district has a population of 481,818. This gives it a ranking of 547th in India (out of a total of 640). The district has a population density of 244 inhabitants per square kilometre (630 /sq mi). Its population growth rate over the decade 2001-2011 was 11.26%. -

RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Spatial Pattern And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Goswami Barooah. Space and Culture, India 2014, 2:1 Page | 24 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Spatial Pattern and Variation in Literacy among the Scheduled Castes Population in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam Dr Momita Goswami Barooah† Abstract Scheduled Caste (SC) population constitutes a sizeable portion of the total population of Assam accounting for 6.32 per cent according to the 2011 Census. They comprise a socially backward class in the Indian society—downtrodden illiterate people of the Indian social fabric. Literacy and educational attainment are considered the hallmark of a modern society. The traits of the modern society, such as, industrialisation, modernisation and urbanisation are closely associated with the level of literacy and education. In the middle part of the 20th century, the literacy rate among them was very low. However, in the later part of the 20th century and in the current millennium due to the developmental measures implemented by both the Central as well as State Governments of India and due to the influence of mass media, there has been a change in the pattern of literacy. The literacy rate of the SC population in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam was 66.34 per cent in 2011 against 61.15 per cent for general population, which is slightly lower than the SC population in the Valley. The study of the pattern of literacy among various social groups of SCs in the study area provides an insight into the socio-economic situations. An attempt has been made in this paper to analyse the spatial pattern of literacy and its variations among the scheduled caste population in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam.