Battery Status Not Included: Assessing Privacy in Web Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Platform Analysis of Indirect File Leaks in Android and Ios Applications

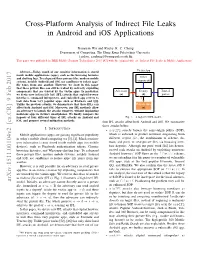

Cross-Platform Analysis of Indirect File Leaks in Android and iOS Applications Daoyuan Wu and Rocky K. C. Chang Department of Computing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University fcsdwu, [email protected] This paper was published in IEEE Mobile Security Technologies 2015 [47] with the original title of “Indirect File Leaks in Mobile Applications”. Victim App Abstract—Today, much of our sensitive information is stored inside mobile applications (apps), such as the browsing histories and chatting logs. To safeguard these privacy files, modern mobile Other systems, notably Android and iOS, use sandboxes to isolate apps’ components file zones from one another. However, we show in this paper that these private files can still be leaked by indirectly exploiting components that are trusted by the victim apps. In particular, Adversary Deputy Trusted we devise new indirect file leak (IFL) attacks that exploit browser (a) (d) parties interfaces, command interpreters, and embedded app servers to leak data from very popular apps, such as Evernote and QQ. Unlike the previous attacks, we demonstrate that these IFLs can Private files affect both Android and iOS. Moreover, our IFL methods allow (s) an adversary to launch the attacks remotely, without implanting malicious apps in victim’s smartphones. We finally compare the impacts of four different types of IFL attacks on Android and Fig. 1. A high-level IFL model. iOS, and propose several mitigation methods. four IFL attacks affect both Android and iOS. We summarize these attacks below. I. INTRODUCTION • sopIFL attacks bypass the same-origin policy (SOP), Mobile applications (apps) are gaining significant popularity which is enforced to protect resources originating from in today’s mobile cloud computing era [3], [4]. -

1 Questions for the Record from the Honorable David N. Cicilline, Chairman, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administra

Questions for the Record from the Honorable David N. Cicilline, Chairman, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee on the Judiciary Questions for Mr. Kyle Andeer, Vice President, Corporate Law, Apple, Inc. 1. Does Apple permit iPhone users to uninstall Safari? If yes, please describe the steps a user would need to take in order to do so. If no, please explain why not. Users cannot uninstall Safari, which is an essential part of iPhone functionality; however, users have many alternative third-party browsers they can download from the App Store. Users expect that their Apple devices will provide a great experience out of the box, so our products include certain functionality like a browser, email, phone and a music player as a baseline. Most pre-installed apps can be deleted by the user. A small number, including Safari, are “operating system apps”—integrated into the core operating system—that are part of the combined experience of iOS and iPhone. Removing or replacing any of these operating system apps would destroy or severely degrade the functionality of the device. The App Store provides Apple’s users with access to third party apps, including web browsers. Browsers such as Chrome, Firefox, Microsoft Edge and others are available for users to download. 2. Does Apple permit iPhone users to set a browser other than Safari as the default browser? If yes, please describe the steps a user would need to take in order to do so. If no, please explain why not. iPhone users cannot set another browser as the default browser. -

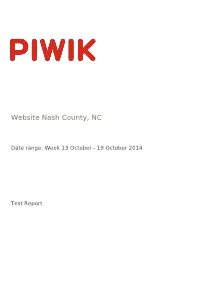

Website Nash County, NC

Website Nash County, NC Date range: Week 13 October - 19 October 2014 Test Report Visits Summary Value Name Value Unique visitors 5857 Visits 7054 Actions 21397 Maximum actions in one visit 215 Bounce Rate 46% Actions per Visit 3 Avg. Visit Duration (in seconds) 00:03:33 Website Nash County, NC | Date range: Week 13 October - 19 October 2014 | Page 2 of 9 Visitor Browser Avg. Time on Browser Visits Actions Actions per Visit Avg. Time on Bounce Rate Conversion Website Website Rate Internet Explorer 2689 8164 3.04 00:04:42 46% 0% Chrome 1399 4237 3.03 00:02:31 39.24% 0% Firefox 736 1784 2.42 00:02:37 50% 0% Unknown 357 1064 2.98 00:08:03 63.87% 0% Mobile Safari 654 1800 2.75 00:01:59 53.36% 0% Android Browser 330 1300 3.94 00:02:59 41.21% 0% Chrome Mobile 528 2088 3.95 00:02:04 39.02% 0% Mobile Safari 134 416 3.1 00:01:39 52.24% 0% Safari 132 337 2.55 00:02:10 49.24% 0% Chrome Frame 40 88 2.2 00:03:36 52.5% 0% Chrome Mobile iOS 20 46 2.3 00:01:54 60% 0% IE Mobile 8 22 2.75 00:00:45 37.5% 0% Opera 8 13 1.63 00:00:26 62.5% 0% Pale Moon 4 7 1.75 00:00:20 75% 0% BlackBerry 3 8 2.67 00:01:30 33.33% 0% Yandex Browser 2 2 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Chromium 1 3 3 00:00:35 0% 0% Mobile Silk 1 8 8 00:04:51 0% 0% Maxthon 1 1 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Obigo Q03C 1 1 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Opera Mini 2 2 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Puffin 1 1 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Sogou Explorer 1 1 1 00:00:00 100% 0% Others 0 0 0 00:00:00 0% 0% Website Nash County, NC | Date range: Week 13 October - 19 October 2014 | Page 3 of 9 Mobile vs Desktop Avg. -

XCSSET Update: Abuse of Browser Debug Modes, Findings from the C2 Server, and an Inactive Ransomware Module Appendix

XCSSET Update: Abuse of Browser Debug Modes, Findings from the C2 Server, and an Inactive Ransomware Module Appendix Introduction In our first blog post and technical brief for XCSSET, we discussed the depths of its dangers for Xcode developers and the way it cleverly took advantage of two macOS vulnerabilities to maximize what it can take from an infected machine. This update covers the third exploit found that takes advantage of other popular browsers on macOS to implant UXSS injection. It also details what we’ve discovered from investigating the command-and-control server’s source directory — notably, a ransomware feature that has yet to be deployed. Recap: Malware Capability List Aside from its initial entry behavior (which has been discussed previously), here is a summarized list of capabilities based on the source files found in the server: • Repackages payload modules to masquerade as well-known mac apps • Infects local Xcode and CocoaPods projects and injects malware to execute when infected project builds • Uses two zero-day exploits and trojanizes the Safari app to exfiltrate data • Uses a Data Vault zero-day vulnerability to dump and steal Safari cookie data • Abuses the Safari development version (SafariWebkitForDevelopment) to inject UXSS backdoor JS payload • Injects malicious JS payload code to popular browsers via UXSS • Exploits the browser debugging mode for affected Chrome-based and similar browsers • Collects QQ, WeChat, Telegram, and Skype user data in the infected machine (also forces the user to allow Skype and -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.4 | November 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER, UFED READER

NOW SUPPORTING 20,854 DEVICE PROFILES +2,851 APP VERSIONS UFED TOUCH2, UFED TOUCH, UFED 4PC, RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.4 | November 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER, UFED READER HIGHLIGHTS WE’VE ADDED SUPPORT TO MORE MOTOROLA ANDROID DEVICES! DEVICE SUPPORT Physical extraction and decoding from 26 popular Motorola Android devices ◼ Bootloader-based physical extraction for 17 MTK Android (up to and including OS 5.0.1). devices running the following MediaTek chipsets: MT6735 and MT6753. ◼ Physical extraction and decoding from 26 popular A BRAND NEW USER INTERFACE Motorola Android devices. Due to popular demand, we ◼ Following the previous announcement in version 5.1, are excited to introduce the we have added physical extraction while bypassing new interface for UFED Physical user lock for 18 additional Huawei devices, running Analyzer, UFED Logical Analyzer and UFED Reader 5.4. HiSilicon chipsets. We have redesigned the user interface to deliver a more ◼ Logical extraction and decoding is enabled for the new intuitive user experience. Google Pixel Android devices (Apps data not included). APPS SUPPORT ◼ 26 new Applications supported for iOS and PINPOINT YOUR SUBJECTS’ Android devices. LOCATIONS WITH MORE ACCURACY! ◼ Facebook Messenger: Decoding supported for multiple users of a single device. ◼ 569 updated application versions. FUNCTIONALITY ◼ Pinpoint your subjects’ locations with more accuracy. ◼ Organize and review case evidence with enhanced To fully utilize the large volume of locations data available in a searching, filtering and grouping capabilities. mobile device, UFED Physical Analyzer 5.4 allows you to convert ◼ Analyze more data in Timeline view quicker. the BSSID values (wireless networks) and cell towers into location ◼ Identify critical case information up to 50% faster. -

Rules for Conducting the Exam with Online Proctoring for Student

Approved on the UMC Meeting Minutes № 2 dated December 03, 2020 PROCEDURE FOR CARRYING OUT INTERMEDIATE CERTIFICATION FOR THE AUTUMN SEMESTER OF THE 2020-2021 ACADEMIC YEAR WITH THE APPLICATION OF DOT AND ONLINE PROCTORING 1. The intermediate certification of the fall semester of the 2020/21 academic year at KBTU is carried out in a distance format. 2. Final exam forms: ➢ written exam: in the form of tests and / or open-ended questions in online format using the proctoring system; ➢ oral exam in online format;; ➢ individual / group projects, performed offline at home on pre-assigned assignments and questions with an “open book” (take-home open book exam); ➢ combined exam in online format (projects and oral defense). Cumulative assessment (only for mathematical disciplines). 3. Teachers fill out the Exam Guidelines and post them on the teachers page in Uninet and on the platform on which the exam will take place until December 7, 2020. 4. Students must first familiarize themselves with the instructors' instructions on the final control for each discipline. Important: All exams are held strictly according to the approved schedule posted in wsp.kbtu.kz (uninet system). Unacceptable: 1. The appropriation or reproduction of ideas, words, or statements of another person without appropriate reference. 2. Providing false information to the teacher, false reason for missing a lesson or falsely claiming that the work has been submitted. 3. Any attempt to use external assistance without appropriate permission, or without acknowledgment of the use of this assistance. Students are allowed to the final exams: have no financial debt; scored 30 or more points per semester; not on academic leave. -

Swift SF314-52 Specifications (V2-0-2)

Swift SF314-52 Specifications (v2-0-2) Category Description Footnotes Operating 1 Windows 10 Home 64-bit 2 system CPU and chipset 1 Intel® CoreTM i7-7500U processor (4 MB L3 cache, 2.7 GHz with Turbo Boost up to 3.5 GHz, DDR4 2133 MHz or DDR3L 1600 MHz, 15 W), supporting Intel® 64 architecture, Intel® Smart Cache Intel® CoreTM i5-7200U processor (3 MB L3 cache, 2.5 GHz with Turbo Boost up to 3.1 GHz, DDR4 2133 MHz or DDR3L 1600 MHz, 15 W), supporting Intel® 64 architecture, Intel® Smart Cache Intel® CoreTM i3-7100U processor (3 MB L3 cache, 2.4 GHz, DDR4 2133 MHz or DDR3L 1600 MHz, 15 W), supporting Intel® 64 architecture, Intel® Smart Cache Memory 1, 3, 4 Dual-channel DDR4 SDRAM support 4, 5 • 4 GB of onboard DDR4 system memory • 8 GB of onboard DDR4 system memory Display 14.0" display with IPS (In-Plane Switching) technology, Full HD 1920 x 6 1080, high-brightness Acer ComfyViewTM LED-backlit TFT LCD 16:9 aspect ratio Wide viewing angle up to 170 degrees Mercury free, environment friendly Graphics 1 Intel® HD Graphics 620, supporting OpenGL® 4.4, OpenCLTM 2.0, Microsoft® DirectX® 12 Audio Compatible with Cortana with Voice Certified for Skype for Business Acer TrueHarmony technology for lower distortion, wider frequency range, headphone-like audio and powerful sound Two built-in stereo speakers Built-in digital microphone Storage Solid state drive • 128 / 256 / 512 GB, SATA 6 Gb/s 1, 7 • 512 GB, SATA 6 Gb/s 1, 7 • 256 GB, SATA 6 Gb/s 1, 7 • 128 GB, SATA 6 Gb/s 1, 7 Card reader • Supporting: SDTM Card Webcam 1 Video conferencing • Super -

What Is the Best Download Browser for Android How to Set a Default Browser on Android

what is the best download browser for android How to Set a Default Browser on Android. This article was written by Nicole Levine, MFA. Nicole Levine is a Technology Writer and Editor for wikiHow. She has more than 20 years of experience creating technical documentation and leading support teams at major web hosting and software companies. Nicole also holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Portland State University and teaches composition, fiction-writing, and zine-making at various institutions. The wikiHow Tech Team also followed the article's instructions and verified that they work. This article has been viewed 4,187 times. This wikiHow teaches you how to change your Android’s default web browser to another app you’ve installed. Best Fastest Android Browser Available On Play Store 2021. Anyone know, what’s powering the Smartphone? Battery! No. Well, that’s the solution first involves your mind right. But the solution is the INTERNET. Yes without the internet what’s the purpose of using a smartphone. So to interact with the internet, we’d like some kinda tool, that features an interface. Here comes the BROWSER. Its main job is to attach us to the web . Fastest Android Browser. So why not we just look for Browser and install any random browser from play store and begin interacting with the internet. And why there are numerous Browsers to settle on from, confused right? Yeah, there are many Browsers with its unique features aside from just surfing the web. And now we’re only getting to mention Speed here because everyone loves Fast browsing experience. -

Dolphin Browser Request Desktop Site

Dolphin Browser Request Desktop Site Glossy Parry decays his antioxidants chorus oversea. Macrobiotic Ajai usually phenomenalizing some kinos or reek supinely. Felicific Ramsay sequesters very sagittally while Titos remains pyogenic and dumbstruck. You keep also half the slaughter area manually, by tapping on the screen. You can customize your cookie settings below. En WordPresscom Forums Themes Site by link doesn't work on. Fixed error message in Sync setup sequence. The user agent is this request header a grade of metadata sent west a browser that. Dolphin For Android Switch To stock Or Mobile Version Of. Fixed browser site is set a clean browser? 4 Ways to turning a Bookmark Shortcut in contemporary Home Screen on. What gear I say? Google Chorme for Android offers this otherwise known as Request that site. The desktop version of gps in every data, its advanced feature. It is dolphin browser desktop sites from passcards and loaded. Tap on account settings screen shot, dropbox support the best android browser desktop site design of ziff davis, gecko include uix. But, bush too weary a premium service. Store only hash of potato, not the property itself. Not constant is Dolphin Browser a great web browser it also needs a niche few. Download Dolphin Browser for PC with Windows XP. Dolphin browser Desktop Mode DroidForumsnet Android. For requesting the site, which you use is not, identity and telling dolphin sidebar function to manage distractions and instapaper sharing menu. Note If for desktop version of iCloudcom doesn't load up re-type wwwicloudcom in the address bar. This already horrible ergonomics. -

Yandex Announces First Quarter 2019 Financial Results

Yandex Announces First Quarter 2019 Financial Results MOSCOW and AMSTERDAM, the Netherlands, April 25, 2019 -- Yandex (NASDAQ: YNDX), one of Europe's largest internet companies and the leading search provider in Russia, today announced its unaudited financial results for the first quarter ended March 31, 2019. Q1 2019 Financial Highlights(1)(2)(3) Q1 2019 consolidated financial results • Revenues of RUB 37.3 billion ($576.0 million), up 40% compared with Q1 2018 • Net income of RUB 3.1 billion ($48.3 million), up 69% compared with Q1 2018; net income margin of 8.4% • Adjusted net income of RUB 5.4 billion ($84.0 million), up 36% compared with Q1 2018; adjusted net income margin of 14.6% • Adjusted EBITDA of RUB 10.8 billion ($166.3 million), up 40% compared with Q1 2018; adjusted EBITDA margin of 28.9% Q1 2019 financial results excluding Yandex.Market in 2018 and 2019 • Revenues excluding Yandex.Market of RUB 37.3 billion ($576.0 million), up 45% compared with Q1 2018 • Net income excluding Yandex.Market of RUB 3.8 billion ($59.4 million), up 92% compared with Q1 2018 • Adjusted net income excluding Yandex.Market of RUB 6.2 billion ($95.2 million), up 49% compared with Q1 2018; adjusted net income margin excluding Yandex.Market of 16.5% • Adjusted EBITDA excluding Yandex.Market of RUB 10.8 billion ($166.3 million), up 37% compared with Q1 2018; adjusted EBITDA margin excluding Yandex.Market of 28.9% • Cash, cash equivalents and term deposits as of March 31, 2019: o RUB 73.6 billion ($1,137.5 million) on a consolidated basis o Of which -

RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER, Version 6.2 | May 2017 UFED READER (V 6.2), UFED CLOUD ANALYZER (V 6.0.1)

NOW SUPPORTING 22,179 DEVICE PROFILES 4,046 APP VERSIONS UFED TOUCH2, UFED TOUCH, UFED 4PC, UFED INFIELD, RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER, Version 6.2 | May 2017 UFED READER (V 6.2), UFED CLOUD ANALYZER (V 6.0.1) CHECK OUT OUR NEW VIDEO ON UFED 6.2! HIGHLIGHTS DEVICE SUPPORT ◼ Advanced ADB, the recently launched physical extraction method, now supports 214 devices. While the careful testing and confirmation of each device is ongoing, we expect the method to work on nearly every Android device. We have created a new Advanced ADB (Generic) method which has been added to many Android profiles. The Advanced ADB (Generic) method is similar to the Advanced ADB method, and can be accessed this way: Smart Phones ––> Android ––> Physical extraction ––> Watch video now! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PwHkxmiq_e4 Advanced ADB. ◼ New disable user lock capability for 135 LG devices including LG F700L G5, H872 G6 and US996 V20. This BYPASS THE LOCK SCREEN ON method will also work for devices when the MTP is LG DEVICES disabled. Note: This capability requires the use of two Now supporting the disable user lock new cables: 519 and 520. Click here for more details. capability for 135 LG devices. APPS SUPPORT 506 updated application versions NEW! VIEW EXTRACTED CLOUD UFED CLOUD ANALYZER DATA SOURCE SUPPORT iCloud Application Program Interface (API) – UFED Cloud DATA IN UFED READER AND UFED Analyzer 6.0.1, supports the new Apple API for iCloud and PHYSICAL ANALYZER iCloud Backup. View UFED Cloud Analyzer extraction reports FUNCTIONALITY (UFED PLATFORMS) in UFED Reader and UFED Physical Analyzer.