Lymantria Dispar Asiatica*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

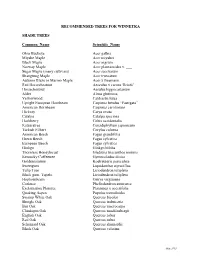

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Beyond the Fringe

Beyond the Fringe By Margaret Klein Wilson, Fairfax Master Gardener Intern The final flourish of native spring flowering trees belongs to fringe trees (Chionanthus virginicus). The measured parade of seasonal color — dogwoods and redbuds, flowering cherry and plum — is neatly capped by the fluttering grace of abundant white blossoms that engulf this small, often edge habitat tree beginning in mid-May. Encountering a fringe tree on a breezy spring day is to see masses of white corollas of petals casting their light perfume across the landscape. Is it any wonder Linnaeus named Yale ©2021 Copyright and noted this genus Chionanthus (chion = University snow; anthos = flower) as he compiled the photo: Genera Plantarum (1753)? Less poetically, fringe tree’s common names include Old Man’s Beard, Grancy graybeard, flowering ash and white fringe tree. Genus Chionanthus is a member of the Olive Family, the Olaceae, which includes 29 genera and over 600 species of trees and shrubs common in southeastern Asia and Australasia. Trees in this genus have uses both practical and ornamental: olive for food, ash for its lumber, and forsythia, gardenia and privets for sheer domestic beauty. In North America, ash trees in the genus Fraxinus, devilwood (Osmantus americanus) and Forestiera (swampprivet) are fringe tree’s near relatives. Only two species of fringe tree exist: C. virginicus in eastern North America and C. retusus, native to China. In his citation naming fringe tree the Virginia Native Plant Society 1997 Wildflower of the Year, C. F. Saachi explains this geographic disconnect: “This unusual biogeographic pattern, with different species within a genus … separated by several thousand miles, is a product of major geologic events including mountain building and the effects of glaciation. -

Range Expansion of Lymantria Dispar Dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) Along Its North‐Western Margin in North America Despite Low Predicted Climatic Suitability

Received: 22 December 2017 | Revised: 9 August 2018 | Accepted: 11 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13474 RESEARCH PAPER Range expansion of Lymantria dispar dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) along its north‐western margin in North America despite low predicted climatic suitability Marissa A. Streifel1,2 | Patrick C. Tobin3 | Aubree M. Kees1 | Brian H. Aukema1 1Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota Abstract 2Minnesota Department of Agriculture, Aim: The European gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar dispar (L.), (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) St. Paul, Minnesota is an invasive defoliator that has been expanding its range in North America follow- 3School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, ing its introduction in 1869. Here, we investigate recent range expansion into a Washington region previously predicted to be climatically unsuitable. We examine whether win- Correspondence ter severity is correlated with summer trap captures of male moths at the landscape Brian Aukema, Department of Entomology, scale, and quantify overwintering egg survivorship along a northern boundary of the University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. Email: [email protected] invasion edge. Location: Northern Minnesota, USA. Funding information USDA APHIS, Grant/Award Number: Methods: Several winter severity metrics were defined using daily temperature data A-83114 13255; National Science from 17 weather stations across the study area. These metrics were used to explore Foundation, Grant/Award Number: – ‐ 1556111; United States Department of associations with male gypsy moth monitoring data (2004 2014). Laboratory reared Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection egg masses were deployed to field locations each fall for 2 years in a 2 × 2 factorial Service, Grant/Award Number: 15-8130- / × / 0577-CA; USDA Forest Service, Grant/ design (north south aspect below above snow line) to reflect microclimate varia- Award Number: 14-JV-11242303-128 tion. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

Gypsy Moth CP

INDUSTRY BIOSECURITY PLAN FOR THE NURSERY & GARDEN INDUSTRY Threat Specific Contingency Plan Gypsy moth (Asian and European strains) Lymantria dispar dispar Plant Health Australia December 2009 Disclaimer The scientific and technical content of this document is current to the date published and all efforts were made to obtain relevant and published information on the pest. New information will be included as it becomes available, or when the document is reviewed. The material contained in this publication is produced for general information only. It is not intended as professional advice on any particular matter. No person should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained in this publication without first obtaining specific, independent professional advice. Plant Health Australia and all persons acting for Plant Health Australia in preparing this publication, expressly disclaim all and any liability to any persons in respect of anything done by any such person in reliance, whether in whole or in part, on this publication. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of Plant Health Australia. Further information For further information regarding this contingency plan, contact Plant Health Australia through the details below. Address: Suite 5, FECCA House 4 Phipps Close DEAKIN ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6215 7700 Fax: +61 2 6260 4321 Email: [email protected] Website: www.planthealthaustralia.com.au PHA & NGIA | Contingency Plan – Asian and European gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) 1 Purpose and background of this contingency plan .............................................................. 5 2 Australian nursery industry .................................................................................................... 5 3 Eradication or containment determination ............................................................................ 6 4 Pest information/status .......................................................................................................... -

Gypsy Moths (Lymantria Spp.) Gypsy Moths Are an Exotic Plant Pest Not Present in Australia

Fact sheet Gypsy moths (Lymantria spp.) Gypsy moths are an exotic plant pest not present in Australia. Originating from China and Far East Russia the Asian gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar asiatica) has now spread and established in Korea, Japan and Europe. The European gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar dispar) which originated from southern Europe and Northern Africa has spread to North America. Gypsy moths pose a high biosecurity risk to Australia because of their tendency to hitchhike and their high reproductive rate. If gypsy moths established in Australia they would be extremely difficult and expensive to manage, partly because of their broad host range. European strains of the gypsy moth hold great potential for damage to commercial radiata pine plantations where Asian gypsy moth female [40-70 mm] (top) male 30-40 mm (bottom) this species is utilised in plantation forestry, such as in Photo: USDA APHIS PPQ Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org New Zealand or Australia. How will it get here? There is a high risk of exotic gypsy moths arriving on ships carrying cargo containers. The gypsy moth is attracted to light, so there is the potential for eggs to be deposited on ships, aircraft and vehicles at brightly lit urban parking lots, airports and seaports. The likelihood of gypsy moth being transported to Australia from any particular country is dependent on a number of factors such as volume of trade, previous ports of call and number of passengers. The four main potential gypsy moth entry pathways identified are imported vehicles and machinery, cargo containers, sea vessels and aircraft, and military equipment. -

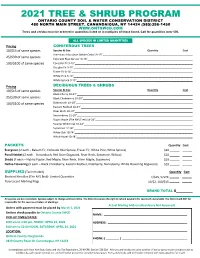

2021 Tree & Shrub Program

2021 TREE & SHRUB PROGRAM ONTARIO COUNTY SOIL & WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT 480 NORTH MAIN STREET, CANANDAIGUA, NY 14424 (585)396-1450 WWW.ONTSWCD.COM Trees and shrubs must be ordered in quantities listed or in multiples of those listed. Call for quantities over 500. ALL SPECIES IN LIMITED QUANTITIES Pricing CONIFEROUS TREES 10/$15 of same species Species & Size Quantity Cost American Arborvitae (White Cedar) 9-15”______________________________________________________________ 25/$30 of same species Colorado Blue Spruce 10-16”_________________________________________________________________________ 100/$100 of same species Concolor Fir 9-15”__________________________________________________________________________________ Douglas Fir 9-15”_________________________________________________________________________________ Fraser Fir 8-14”____________________________________________________________________________________ White Pine 6-14”___________________________________________________________________________________ White Spruce 9-15”_________________________________________________________________________________ Pricing DECIDUOUS TREES & SHRUBS 10/$15 of same species Species & Size Quantity Cost Black Cherry 18-24”________________________________________________________________________________ 25/$30 of same species Black Chokeberry 10-20”____________________________________________________________________________ 100/$100 of same species Buttonbush 10-18”_________________________________________________________________________________ -

Liquidambar Styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia

43 Banisteria, Number 9, 1997 © 1997 by the Virginia Natural History Society An Abnormal Variant of Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia Bruce L. King Department of Biology Randolph Macon College Ashland, Virginia 23005 Leaves of individuals of Liquidambar styraciflua L. Similar measurements were made from surrounding (sweetgum) - are predominantly 5-lobed, occasionally 7- plants in three height classes:, early sapling, 61-134 cm; lobed or 3-lobed (Radford et al., 1968; Cocke, 1974; large seedlings, 10-23 cm; and small seedlings (mostly first Grimm, 1983; Duncan & Duncan, 1988). The tips of the year), 3-8.5 cm. All of the small seedlings were within 5 lobes are acute and leaf margins are serrate, rarely entire. meters of the atypical specimen and most of the large In 1991, I found a seedling (2-3 yr old) that I seedlings and saplings were within 10 meters. The greatest tentatively identified as a specimen of Liquidambar styrac- distance between any two plants was 70 meters. All of the iflua. The specimen occurs in a 20 acre section of plants measured were in dense to moderate shade. In the deciduous forest located between U.S. Route 1 and seedling classes, three leaves were measured from each of Waverly Drive, 3.2 km south of Ladysmith, Caroline ten plants (n = 30 leaves). In the sapling class, counts of County, Virginia. The seedling was found at the middle leaf lobes and observations of lobe tips and leaf margins of a 10% slope. Dominant trees on the upper slope were made from ten leaves from each of 20 plants (n include Quercus alba L., Q. -

General-Poster

XXIV International Congress of Entomology General-Poster > 157 Section 1 Taxonomy August 20-22 (Mon-Wed) Presentation Title Code No. Authors_Presenting author PS1M001 Madagascar’s millipede assassin bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Ectrichodiinae): Taxonomy, phylogenetics and sexual dimorphism Michael Forthman, Christiane Weirauch PS1M002 Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Papilio memnon complex suggests multiple origins of mimetic colour pattern and sexual dimorphism Chia-Hsuan Wei, Matheiu Joron, Shen-HornYen PS1M003 The evolution of host utilization and shelter building behavior in the genus Parapoynx (Lepidoptera: Crambidae: Acentropinae) Ling-Ying Tsai, Chia-Hsuan Wei, Shen-Horn Yen PS1M004 Phylogenetic analysis of the spider mite family Tetranychidae Tomoko Matsuda, Norihide Hinomoto, Maiko Morishita, Yasuki Kitashima, Tetsuo Gotoh PS1M005 A pteromalid (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) parasitizing larvae of Aphidoletes aphidimyza (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) and the fi rst fi nding of the facial pit in Chalcidoidea Kazunori Matsuo, Junichiro Abe, Kanako Atomura, Junichi Yukawa PS1M006 Population genetics of common Palearctic solitary bee Anthophora plumipes (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae) in whole species areal and result of its recent introduction in the USA Katerina Cerna, Pavel Munclinger, Jakub Straka PS1M007 Multiple nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analyses support a cryptic species complex of the global invasive pest, - Poster General Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Chia-Hung Hsieh, Hurng-Yi Wang, Cheng-Han Chung, -

Effects of Rearing Density on Developmental Traits of Two Different Biotypes of the Gypsy Moth, Lymantria Dispar L., from China and the USA

insects Communication Effects of Rearing Density on Developmental Traits of Two Different Biotypes of the Gypsy Moth, Lymantria Dispar L., from China and the USA Yiming Wang 1, Robert L. Harrison 2 and Juan Shi 1,* 1 Sino-France Joint Laboratory for Invasive Forest Pests in Eurasia, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] 2 Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD 20705, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-13011833628; Fax: +86-10-62336423 Simple Summary: The gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, is a forest pest that is grouped into two biotypes: the European gypsy moth (EGM), found in Europe and North America; and the Asian gypsy moth (AGM), found in China, Russia, Korea, and Japan. Outbreaks of this pest result in high-density populations of larvae that can cause enormous damage to trees and forests. Studies have identified an influence of larval population density on gypsy moth development, but it is not known how EGM and AGM populations differ in their response to changing larval densities. We examined the effects of varying larval density on three colonies established from one EGM population and two AGM populations. All three colonies exhibited an optimal degree of larval survival and optimal rates of pupation and adult emergence at an intermediate density of five larvae/rearing container. The duration of larval development was fastest at the same intermediate density for all three colonies. Although differences in larval development time, survival, pupation and emergence were observed among the three colonies under the conditions of our study, our findings indicate Citation: Wang, Y.; Harrison, R.L.; that density-dependent effects on the development of different gypsy moth biotypes follow the Shi, J. -

Pdf/Curvefit.Pdf) (Retrieved 1 Affect Preference and Performance of Gypsy Moth Caterpillars

Environmental Entomology, 46(4), 2017, 1012–1023 doi: 10.1093/ee/nvx111 Advance Access Publication Date: 4 July 2017 Physiological Ecology Research Effects of Temperature on Development of Lymantria dispar asiatica and Lymantria dispar japonica (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) Samita Limbu,1 Melody Keena,2 Fang Chen,3 Gericke Cook,4 Hannah Nadel,5 and Kelli Hoover1,6 1Department of Entomology and Center for Chemical Ecology, The Pennsylvania State University, 501 ASI Bldg., University Park, PA 16802 ([email protected]; [email protected]), 2U. S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, 51 Mill Pond Rd., Hamden, CT 06514 ([email protected]), 3Forestry Bureau of Jingzhou, –14 Jingzhou North Rd., Jingzhou, Hubei, China 434020 ([email protected]), 4USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, PPQ CPHST, 2301 Research Blvd, Suite 108, Fort Collins, CO 80526 ([email protected]), 5USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, PPQ S & T, 1398 West Truck Rd., Buzzards Bay, MA 02542 ([email protected]), and 6Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the Forest Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. Subject Editor: Kelly Johnson Received 18 January 2017; Editorial decision 1 June 2017 Abstract Periodic introductions of the Asian subspecies of gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar asiatica Vnukovskij and Lymantria dispar japonica Motschulsky, in North America are threatening forests and interrupting foreign trade. -

Check List of Noctuid Moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae And

Бiологiчний вiсник МДПУ імені Богдана Хмельницького 6 (2), стор. 87–97, 2016 Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University, 6 (2), pp. 87–97, 2016 ARTICLE UDC 595.786 CHECK LIST OF NOCTUID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE AND EREBIDAE EXCLUDING LYMANTRIINAE AND ARCTIINAE) FROM THE SAUR MOUNTAINS (EAST KAZAKHSTAN AND NORTH-EAST CHINA) A.V. Volynkin1, 2, S.V. Titov3, M. Černila4 1 Altai State University, South Siberian Botanical Garden, Lenina pr. 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology, Lenina pr. 36, 634050, Tomsk, Russia 3 The Research Centre for Environmental ‘Monitoring’, S. Toraighyrov Pavlodar State University, Lomova str. 64, KZ-140008, Pavlodar, Kazakhstan. E-mail: [email protected] 4 The Slovenian Museum of Natural History, Prešernova 20, SI-1001, Ljubljana, Slovenia. E-mail: [email protected] The paper contains data on the fauna of the Lepidoptera families Erebidae (excluding subfamilies Lymantriinae and Arctiinae) and Noctuidae of the Saur Mountains (East Kazakhstan). The check list includes 216 species. The map of collecting localities is presented. Key words: Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Erebidae, Asia, Kazakhstan, Saur, fauna. INTRODUCTION The fauna of noctuoid moths (the families Erebidae and Noctuidae) of Kazakhstan is still poorly studied. Only the fauna of West Kazakhstan has been studied satisfactorily (Gorbunov 2011). On the faunas of other parts of the country, only fragmentary data are published (Lederer, 1853; 1855; Aibasov & Zhdanko 1982; Hacker & Peks 1990; Lehmann et al. 1998; Benedek & Bálint 2009; 2013; Korb 2013). In contrast to the West Kazakhstan, the fauna of noctuid moths of East Kazakhstan was studied inadequately.