Jynx Torquilla)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 4 A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Madeeha Manzoor Center for Bioresource Research Adila Nazli Center for Bioresource Research, [email protected] Sabiha Shamim Center for Bioresource Research Fida Muhammad Khan Center for Bioresource Research Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Manzoor, M., Nazli, A., Shamim, S., & Khan, F. M. (2017). A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts, Journal of Bioresource Management, 4 (1). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.7102.0067 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: May 29, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study on Avifauna Present in Different Zones of Chitral Districts Erratum Added the complete list of author names © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal of Bioresource Management does not grant you any other rights in relation to this website or the material on this website. In other words, all other rights are reserved. For the avoidance of doubt, you must not adapt, edit, change, transform, publish, republish, distribute, redistribute, broadcast, rebroadcast or show or play in public this website or the material on this website (in any form or media) without appropriately and conspicuously citing the original work and source or Journal of Bioresource Management’s prior written permission. -

(Dendrocopos Syriacus) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocoptes Medius) Around Yasouj City in Southwestern Iran

Archive of SID Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics (IJAB) Vol.15, No.1, 99-105, 2019 ISSN: 1735-434X (print); 2423-4222 (online) DOI: 10.22067/ijab.v15i1.81230 Comparison of nest holes between Syrian Woodpecker (Dendrocopos syriacus) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocoptes medius) around Yasouj city in Southwestern Iran Mohamadian, F., Shafaeipour, A.* and Fathinia, B. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Yasouj University, Yasouj, Iran (Received: 10 May 2019; Accepted: 9 October 2019) In this study, the nest-cavity characteristics of Middle Spotted and Syrian Woodpeckers as well as tree characteristics (i.e. tree diameter at breast height and hole measurements) chosen by each species were analyzed. Our results show that vertical entrance diameter, chamber vertical depth, chamber horizontal depth, area of entrance and cavity volume were significantly different between Syrian Woodpecker and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (P < 0.05). The average tree diameter at breast height and nest height between the two species was not significantly different (P > 0.05). For both species, the tree diameter at breast height and nest height did not significantly correlate. The directions of nests’ entrances were different in the two species, not showing a preferentially selected direction. These two species chose different habitats with different tree coverings, which can reduce the competition between the two species over selecting a tree for hole excavation. Key words: competition, dimensions, nest-cavity, primary hole nesters. INTRODUCTION Woodpeckers (Picidae) are considered as important excavator species by providing cavities and holes to many other hole-nesting species (Cockle et al., 2011). An important part of habitat selection in bird species is where to choose a suitable nest-site (Hilden, 1965; Stauffer & Best, 1982; Cody, 1985). -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

A Eurasian Wryneck Speciment from Southern Indian

A EurasianWryneck specimen from southern Indiana JohnB. Dunning,Jr. Amanda Beheler head of the natural resources division at Crane. Andrews also did not rec- Michael Crowder ognizethe bird, and neither he norMr. Crowdercould find a goodmatch Departmentof Forestryand Natural Resources in the North Americanfield guides present at the naturalresource office PurdueUniversity Knowingthat wildlife faculty and students from Purdue University would WestLafayette, Indiana 47907-1159 be workingat Cranein the spring,Andrews placed the specimenin h•s office freezer. Several months later Beheler,then a Ph.D. candidate in the Steve Andrews Departmentof Forestryand Natural Resourcesat Purdue,arrived at NaturalResources Building NSWC Crane to begin her annualfield researchon EasternPhoebes Code 09228 (Sayornisphoebe).Andrews showed her the specimen, but shealso did not Naval Surface Warfare Center recognizeit. The detailsof itsdiscovery were vague, because the nameand Crane,Indiana 47522 contactinformation of thefinder had disappeared during the intervemng months.Beheler transported the bird to Purdue,while Andrews tried to Ron Weiss relocate the individual who found the bird. Ch•pperWoods Bird Observatory Bythe time Behder arrived home, she had checked a numberof North 10329North New Jersey Street andCentral American field guides to no avail..Shecalled Dunning, a fac- Indianapolis,Indiana 46280 tfitymember in her departmentat Purdue,and told him aboutthe find WhenDunning arrived at the Behelerhouse 30 minuteslater to seethe ABSTRACT specimen,Amanda and her husbandBrian had identifiedthe bird as a In February2000, a deadbird found by a workerat theCrane Naval Surface EurasianWryneck (Jynx torquilla) using a Europeanfield guide. Dunning WarfareCenter in southernIndiana proved to be a EurasianWryneck concurredwith theidentification, although neither he norBeheler had any (Jynxtorquilla), a species recorded only once before in NorthAmerica. -

Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, Member of Albatros Media Group, 2020

✹ Tomáš Tůma Tomáš ✹ ✹ We all know that there are many birds in the sky, but did you know that there is a similar Encyclopaedia vast number on our planet’s surface? The bird kingdom is weird, wonderful, vivid ✹ of Birds and fascinating. This encyclopaedia will introduce you to over a hundred of the for Young Readers world’s best-known birds, as well as giving you a clear idea of the orders in which birds ✹ ✹ are classified. You will find an attractive selection of birds of prey, parrots, penguins, songbirds and aquatic birds from practically every corner of Planet Earth. The magnificent full-colour illustrations and easy-to-read text make this book a handy guide that every pre- schooler and young schoolchild will enjoy. Tomáš Tůma www.b4upublishing.com Readers Young Encyclopaedia of Birds for © Designed by B4U Publishing, member of Albatros Media Group, 2020. ean + isbn Two pairs of toes, one turned forward, ✹ Toco toucan ✹ Chestnut-eared aracari ✹ Emerald toucanet the other back, are a clear indication that Piciformes spend most of their time in the trees. The beaks of toucans and aracaris The diet of the chestnut-eared The emerald toucanet lives in grow to a remarkable size. Yet aracari consists mainly of the fruit of the mountain forests of South We climb Woodpeckers hold themselves against tree-trunks these beaks are so light, they are no tropical trees. It is found in the forest America, making its nest in the using their firm tail feathers. Also characteristic impediment to the birds’ deft flight lowlands of Amazonia and in the hollow of a tree. -

Bird Observer VOLUME 37, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2009 HOT BIRDS

Bird Observer VOLUME 37, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2009 HOT BIRDS Marshall Iliff found and photographed this LeConte’s Sparrow (left) on October 20, 2009, at Cumberland Farms in Halifax/Middleboro. On October 21, 2009, Jeff Johnstone found a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (right) at the Orange Airport, and later that day Bob Stymeist took this photograph. Cumberland Farms is a fall hotspot. On November 4, 2009, Jim Sweeney discovered a Lark Bunting (left), and later that day Wayne Petersen took this image. On November 17, 2009, Paul Petersen discovered this MacGillivray’s Warbler (right) in the Victory Gardens in Boston’s Fenway. On November 22, Phil Brown took this fabulous portrait. Rick Heil found this Mew Gull (left), possibly of the Kamchatka race, on November 26, 2009, in Gloucester Harbor. Phil Brown took this great photo in Brace’s Cove on December 7, 2009. CONTENTS BIRDING BY BICYCLE ON THE NASHUA RIVER RAIL TRAIL David Deifik 333 HEY, CAPTAIN, THE BIRDS ARE OVER THERE Frederick Wasti 340 THE POLITICAL LANDSCAPE: DARK CITY Jennifer Ryan and Christina McDermott 344 NOT JUST ANOTHER BIRDING CONTEST —THIS IS THE SUPERBOWL! David Larson 346 FIELD NOTES Two Observations of Walking or Running by Northern Flickers, Colaptes auratus Jim Berry 349 Notes on Nestling Coloration and Feeding Frequency in the Eastern Wood-Pewee, Contopus virens Jim Berry 350 Update on Lesser Black-backed Gull Julie Ellis 362 Specimen of a Eurasian Tree Sparrow Found Dead in a Shipping Container from China Tom French 353 A COMPARISON OF THE AVIAN COMMUNITIES IN WINTER IN A FOREST AND ADJACENT SUBURB William E. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

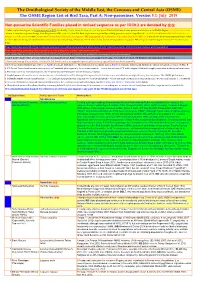

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Pdf 184.33 K

Iranian Journal of Animal Biosystematics (IJAB) Vol.15, No.1, 99-105, 2019 ISSN: 1735-434X (print); 2423-4222 (online) DOI: 10.22067/ijab.v15i1.81230 Comparison of nest holes between Syrian Woodpecker ( Dendrocopos syriacus ) and Middle Spotted Woodpecker ( Dendrocoptes medius ) around Yasouj city in Southwestern Iran Mohamadian, F., Shafaeipour, A.* and Fathinia, B. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Yasouj University, Yasouj, Iran (Received: 10 May 2019; Accepted: 9 October 2019) In this study, the nest-cavity characteristics of Middle Spotted and Syrian Woodpeckers as well as tree characteristics (i.e. tree diameter at breast height and hole measurements) chosen by each species were analyzed. Our results show that vertical entrance diameter, chamber vertical depth, chamber horizontal depth, area of entrance and cavity volume were significantly different between Syrian Woodpecker and Middle Spotted Woodpecker (P < 0.05). The average tree diameter at breast height and nest height between the two species was not significantly different (P > 0.05). For both species, the tree diameter at breast height and nest height did not significantly correlate. The directions of nests’ entrances were different in the two species, not showing a preferentially selected direction. These two species chose different habitats with different tree coverings, which can reduce the competition between the two species over selecting a tree for hole excavation. Key words: competition, dimensions, nest-cavity, primary hole nesters. INTRODUCTION Woodpeckers (Picidae) are considered as important excavator species by providing cavities and holes to many other hole-nesting species (Cockle et al ., 2011). An important part of habitat selection in bird species is where to choose a suitable nest-site (Hilden, 1965; Stauffer & Best, 1982; Cody, 1985). -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Nature for People a Biodiversity Action Plan for Enfield Adopted September 2011

Nature for People A Biodiversity Action Plan for Enfield Adopted September 2011 www.enfield.gov.uk Foreword Enfield is one of London’s greenest boroughs. With Partnership, Natural England and the Environment the Lee Valley Regional Park, private gardens and 123 Agency to get the action plan up and running, and are parks and public open spaces, 37 allotment sites, more already getting to work on some of the objectives. than 300 hectares of woodland and 100 kilometres of We need to do all we can to protect and enhance rivers and streams, we have a wealth of biodiversity Enfield’s rich wildlife heritage for everyone to enjoy, both right here on our doorstep. now and in the future. Enfield is home to some important populations of nationally and internationally scarce plant and animal species like the great crested newt, and the black redstart (a robin-sized bird) which has been spotted in the east of the borough, and some nationally scarce habitats such as our acid grassland. The Biodiversity Action Plan is about more than protecting our wildlife - conserving and enhancing biodiversity contributes to our health and wellbeing and our economic prosperity, ensuring that we are well placed to adapt to the threat of climate change. Providing quality and biodiverse green spaces for people to enjoy their free time improves the quality of Councillor Del Goddard life for everyone who lives here. Cabinet Member for Regeneration Maintaining and enhancing the borough’s biodiversity and Improving Localities is a task for us all. The Council has a community leadership role and responsibility to conserve, protect and enhance our natural habitats. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

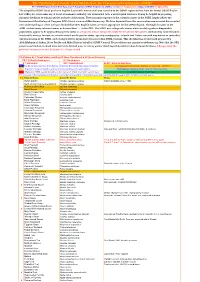

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

The Ecological Determinants of Wryneck Occurrence

Food or nesting place? Identifying factors limiting wryneck populations Master thesis der Philosophisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bern submitted by Valérie Coudrain 2009 Supervision Prof. Raphaël Arlettaz PD Michael Schaub Institute of Ecology and Evolution Division of Conservation Biology Table of contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 2. MATERIAL AND METHODS..................................................................................... 6 2.1 HABITAT REQUIREMENTS OF WRYNECKS ..................................................... 7 2.1.1 Sampling design ............................................................................................... 7 2.1.2 Habitat mapping ............................................................................................... 8 2.1.3 Food resources .................................................................................................. 9 2.1.4 Statistical analyses .......................................................................................... 9 2.2 ANT ABUNDANCE MODELLING ......................................................................... 10 2.2.1 Sampling design ............................................................................................. 10 2.2.2 Ant nest detection probability ..................................................................