An Exploration Into What Extent the Filmmakers of Making a Murderer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chavez 1 Kayla Chavez Peters Engl 499 29 September 2012 The

Chavez 1 Kayla Chavez Peters Engl 499 29 September 2012 The Purpose of Law in Literature “Forgive me, gentlemen of the jury, but there is a human life here, and we must be more careful.” -The Brothers Karamazov Law is an attempt to make order out of chaos, to focus and define a small part of our world which, as a whole, we may never comprehend. It is necessary to every society, as a way of organizing our world and making sense of our interactions with each other. We submit to law, trusting it will protect us from each other, and defend our property and lives, so that we can function in society without constant worry. Inevitably however, law will sometimes fail our expectations, and because of this, many lose sight of law's importance, alienating the field with accusations of inhumanity because they are so disappointed. The emerging field of Law and Literature recognizes the flaws in the legal system and seeks to remind people of law's intention to uphold order and protect people. Law and Literature does this by examining legal scenes in literature to determine what their meaning is in the story, as well as what insights the literature provides into the nature of the legal profession. While literature should not be looked at as a savior of law's purpose, using literary theory to look at law, or looking at literary depictions of law, can help us understand that the legal process is an imperfect human creation. Using ideas from the relatively new field of Law and Literature to analyze legal scenes from classic texts, (Herman Melville's Billy Budd, Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, and Franz Chavez 2 Kafka's The Trial respectively) I will turn the elements of despair or cruelty into spotlights which point out the necessity of law, and support the belief that we should constantly work towards its improvement. -

Usability and User Experience in the True Crime

Running head: SERIALIZED KILLING 1 SERIALIZED KILLING: USABILITY AND USER EXPERIENCE IN THE TRUE CRIME GENRE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY CATHERINE M. TRAYLOR DR. KEVIN T. MOLONEY – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2019 SERIALIZED KILLING 2 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Kevin Moloney, who consistently allowed this paper to be my own work while steering me in the right direction, providing a fresh perspective, and patiently responding to a multitude of emails. I would also like to acknowledge my committee members Dr. Jennifer Palilonis and Dr. Kristen McCauliff. I am grateful to them for their valuable comments on my work and support throughout the process. My deep appreciation goes to my survey respondents and focus group participants for their candid responses and willingness to give of their time. Special thanks to my parents, who always made education a priority in our home and a possibility in my life. Finally, thank you to Zach McFarland for enduring countless nights of thesis edits and reworks. Your patience and encouragement did not go unnoticed. SERIALIZED KILLING 3 Abstract THESIS: SerialiZed Killing: Usability and User Experience in the True Crime Genre STUDENT: Catherine M. Traylor DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication, Information and Media DATE: July 2019 PAGES: 31 True crime, a genre that has piqued the interest of individuals for decades, has taken on a new form in the age of digital media. Through television shows, podcasts, books, and community- driven online forums, investigations of the coldest of cases are met with newfound enthusiasm and determination from professional storytellers and armchair detectives alike. -

Fundamental Fairness Denied

RAINING ON THE WEST MEMPHIS PARADE: FUNDAMENTAL FAIRNESS DENIED The West Memphis 3 are free!! Yea! Three men convicted in the 1993 murders of three boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, were ordered released after entering new pleas following a court hearing, prosecutor Scott Ellington said Friday. Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley Jr. and Jason Baldwin pleaded guilty and were sentenced to 18 years in prison with credit for time served, a prosecutor said. They were to be released on Friday. The three entered what is known as an Alford plea, which allows a defendant to maintain innocence while simultaneously acknowledging that the state has evidence to convict, Ellington said. Cause for celebration, right? Not here; I feel nothing but sweet sorrow because, while Damien Echols (who had actually been on death row most all of the intervening time), Jessie Misskelley Jr. and Jason Baldwin are free, a solid little chunk of the American justice system, due process and fundamental fairness was sacrificed in the process. Let one of the three, Mr. Baldwin, speak for himself and me here: This was NOT justice. I did not want to take this deal, but they were going to kill Damien an I couldn’t let that happen. And therein lies the huge rub. The facts had never been particularly solid against these three once young men. They were brow beaten by avaricious prosecutors, sought to be lynched by a southern community ginned up on fear, horror and emotion and poorly served by their attorneys at the original trial level. In short, every facet of the American system of due process was compromised and tainted, and they have sat convicted, one on death row, ever since as a result. -

Habeas Corpus: the Wrongful Imprisonment of Steven Avery

Peer Reviewed Proceedings of the 7th Annual Conference Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand (PopCAANZ), Sydney, 29 June–1 July, 2016, pp. 11-20. ISBN: 978-0-473-38284-1. © 2016 RACHEL FRANKS State Library of New South Wales; The University of Sydney KIM D. WEINERT Bond University Habeas Corpus: the wrongful imprisonment of Steven Avery ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The politics of the body have been debated at length; ideas of moral and Steven Avery natural rights to protect individual autonomy have been presented in the Habeas context of class, gender and race for centuries. Such sovereignty has been Corpus entrenched in law through the recourse of habeas corpus: the right of Imprisonment redress for unlawful detention or imprisonment before a court. This paper Making a looks at habeas corpus through the lens of the recent ten-part documentary, Murderer Making a Murderer (2015), created by Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, Social media and streamed on Netflix. This web-television series unpacks the wrongful Television imprisonment of Steven A. Avery (who served eighteen years for rape), and posits the recent imprisonments of Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey, both serving life sentences for murder, are also wrongful. This paper also provides a brief overview of the history of the writ of habeas corpus and offers an outline for the continuing importance – within the justice system and within popular culture – of this legal right. INTRODUCTION The politics of the body have been debated at great length; lawyers, philosophers, politicians and sociologists often jostling for position around ideas of moral and natural rights to protect individual autonomy. -

Damien Echols

HIGH MAGICK A GUIDE TO THE SPIRITUAL PRACTICES THAT SAVED MY LIFE ON DEATH ROW DAMIEN ECHOLS BOULDER, COLORADO CONTENTS List of Illustrations . xi Acknowledgments . xiii Foreword by Eddie Vedder . xv PREFACE My Story . xvii PART I AN INTRODUCTION TO MAGICK 1 Why Learn Magick? . 3 2 What Magick Is and What Magick Isn’t . 5 PART II PRELIMINARIES 3 Why Spell Books Don’t Work . 17 4 As Above, So Below: The Power of Attention . 19 PRACTICE Directing Your Attention . 24 5 Training Your Mind . 27 PRACTICE Five Basic Meditations . 29 6 The Magick of Visualization . 33 PRACTICE Visualization . 34 7 Raising and Directing Energy . 37 PRACTICE Raising Energy: Phase 1 . 38 PRACTICE Raising Energy: Phase 2 . 39 vii CONTENTS 8 Working with Doubt . 43 9 Personalizing Your Practice and Getting Started . 45 PART III FUNDAMENTAL PRACTICES OF MAGICK 10 Practicing Variations of the Fourfold Breath . 51 PRACTICE The Fourfold Breath: Quick Version . 52 PRACTICE The Fourfold Breath with Visualization . 53 Solar Application . 55 PRACTICE The Fourfold Solar Breath Application: Version 1 . 56 PRACTICE The Fourfold Solar Breath Application: Version 2 . 59 Lunar Application . 60 PRACTICE The Fourfold Lunar Breath Application: Version 1 . 61 PRACTICE The Fourfold Lunar Breath Application: Version 2 . 62 Seasonal Application . 63 PRACTICE The Fourfold Seasonal Breath Application. 65 INTERLUDE Some History of Magick . 69 11 The Middle Pillar . 73 PRACTICE Performing the Middle Pillar Ritual . 76 PRACTICE Circulating Energy with the Middle Pillar . 81 12 The Qabalistic Cross . 85 PRACTICE Qabalistic Cross Meditation: Version 1 (Traditional) . 91 PRACTICE Qabalistic Cross Meditation: Version 2 . 94 13 The Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram . -

Ethics in the American Criminal Justice System

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Honors Program Theses Honors Program 2016 Liberty and justice for all? : Ethics in the American criminal justice system Haley Hasenstein University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Haley Hasenstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Hasenstein, Haley, "Liberty and justice for all? : Ethics in the American criminal justice system" (2016). Honors Program Theses. 245. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/hpt/245 This Open Access Honors Program Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIBERTY AND JUSTICE FOR ALL?: Ethics in the American Criminal Justice System A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Designation University Honors Haley Hasenstein University of Northern Iowa May 2016 This Study by: Haley Hasenstein Entitled: Liberty and Justice for All?: Ethics in the American Criminal Justice System has been approved as meeting the thesis or project requirement for the Designation University Honors __________ ______________________________________________________ Date Dr. Gayle Rhineberger-Dunn, Honors Thesis Advisor, Criminology ________ ______________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jessica Moon, Director, University Honors Program 2 Abstract The American Bar Association (ABA) claims a commitment to ethics for all that fall under its jurisdiction. As a part of the Bar Exam that lawyers must take to join the Association they are issued a character and fitness test, where some prior misbehavior may disqualify an individual from becoming barred. -

Maclauchlin, Scott a - DOC

MacLauchlin, Scott A - DOC From: Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 9:14 AM To: Meisner, Michael F - DOC; Tarr, David R - DOC Subject: RE: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Should mailroom be pulling any information that comes in from IWW addressed to inmates? From: Meisner, Michael F - DOC Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 7:42 AM To: Tarr, David R - DOC; Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Schwochert, James R - DOC Sent: Sunday, August 21, 2016 6:59 PM To: DOC DL DAI Wardens CO Dir Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Jess, Cathy A - DOC Sent: Friday, August 19, 2016 3:04 PM To: Schwochert, James R - DOC; Weisgerber, Mark L - DOC Cc: Hove, Stephanie R - DOC; Clements, Marc W - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI Indiana information on September 9 possible work stoppage of inmates. From: Basinger, James [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, August 18, 2016 7:44 PM To: Joseph Tony Stines Subject: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Just an FYI on Intel we got today. I would check your systems and databases for Randall Paul Mayhugh, of Terre Haute, IN. Mr. Mayhugh poses as a Union member for a group that call themselves Industrial Workers of the world (IWW). Let know if you find anything. Be safe ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Looks like Leonard McQuay and one of his outside associates are attempting to facilitate involve my in this movement. I know offender McQuay quite well and it doesn't surprise me that we would try to initiate this type of action. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

1 Planning to Binge: How Consumers Choose to Allocate Time to View

1 Planning to Binge: How Consumers Choose to Allocate Time to View Sequential Versus Independent Media Content PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM AUTHORS June 2017 Joy Lu Doctoral Candidate in Marketing University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Uma Karmarkar Assistant Professor Marketing Harvard Business School [email protected] Vinod Venkatraman Assistant Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management Temple University [email protected] Acknowledgement: The authors thank Deborah Small for providing helpful comments and suggestions. 2 Planning to Binge: How Consumers Choose to Allocate Time to View Sequential Versus Independent Media Content ABSTRACT As streaming media online has become more common, several firms have embraced the phenomenon of “binge-watching” by offering their customers entire seasons of a television-style series at one time instead of releasing individual episodes weekly. However, the popularity of binge-watching seems to conflict with prior research suggesting that consumers prefer to savor enjoyable experiences by delaying them or spreading them out. Here we demonstrate how to reconcile these issues using both experimental studies and field data. We examine binge- watching preferences both when people are planning to consume and in the moment of consumption. Our studies show that binge-watching is more likely to be preferred when individual episodes are perceived to be sequential and connected, as opposed to when events are independent with points of closure. Furthermore, this pattern may occur because consumers experience increased utility from completing sequential content. These findings have implications for how firms might frame or divide up their content in ways that allow them to tailor their promotion and pricing to a range of consumer preferences. -

West of Memphis

Mongrel Media Presents WEST OF MEMPHIS A film by Amy Berg (146 min., USA, 2012) Language: English Official Selection Sundance Film Festival 2012 Toronto Film Festival 2012 Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html WEST OF MEMPHIS Synopsis A new documentary written and directed by Academy Award nominated filmmaker, Amy Berg (DELIVER US FROM EVIL) and produced by first time filmmakers Damien Echols and Lorri Davis, in collaboration with the multiple Academy Award winning team of Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh, WEST OF MEMPHIS tells the untold story behind an extraordinary and desperate fight to bring the truth to light; a fight to stop the State of Arkansas from killing an innocent man. Starting with a searing examination of the police investigation into the 1993 murders of three, eight year old boys Christopher Byers, Steven Branch and Michael Moore in the small town of West Memphis, Arkansas, the film goes on to uncover new evidence surrounding the arrest and conviction of the other three victims of this shocking crime – Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley. All three were teenagers when they became the target of the police investigation; all three went on to lose 18 years of their lives - imprisoned for crimes they did not commit. How the documentary came to be, is in itself a key part of the story of Damien Echols’ fight to save his own life. -

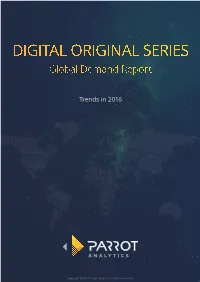

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report

DIGITAL ORIGINAL SERIES Global Demand Report Trends in 2016 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. All rights reserved. Digital Original Series — Global Demand Report | Trends in 2016 Executive Summary } This year saw the release of several new, popular digital } The release of popular titles such as The Grand Tour originals. Three first-season titles — Stranger Things, and The Man in the High Castle caused demand Marvel’s Luke Cage, and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the for Amazon Video to grow by over six times in some Life — had the highest peak demand in 2016 in seven markets, such as the UK, Sweden, and Japan, in Q4 of out of the ten markets. All three ranked within the 2016, illustrating the importance of hit titles for SVOD top ten titles by peak demand in nine out of the ten platforms. markets. } Drama series had the most total demand over the } As a percentage of all demand for digital original series year in these markets, indicating both the number and this year, Netflix had the highest share in Brazil and popularity of titles in this genre. third-highest share in Mexico, suggesting that the other platforms have yet to appeal to Latin American } However, some markets had preferences for other markets. genres. Science fiction was especially popular in Brazil, while France, Mexico, and Sweden had strong } Non-Netflix platforms had the highest share in Japan, demand for comedy-dramas. where Hulu and Amazon Video (as well as Netflix) have been available since 2015. Digital Original Series with Highest Peak Demand in 2016 Orange Is Marvels Stranger Things Gilmore Girls Club De Cuervos The New Black Luke Cage United Kingdom France United States Germany Mexico Brazil Sweden Russia Australia Japan 2 Copyright © 2017 Parrot Analytics. -

How “Making a Murderer” Went Wrong

Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter A Critic at Large JANUARY 25, 2016 ISSUE Dead Certainty How “Making a Murderer” goes wrong. BY KATHRYN SCHULZ A private investigative project, bound by no rules of procedure, is answerable only to ratings and the ethics of its makers. ILLUSTRATION BY SIMON PRADES rgosy began in 1882 as a magazine for children and ceased publication ninety-six years later as Asoft-core porn for men, but for ten years in between it was the home of a true-crime column by Erle Stanley Gardner, the man who gave the world Perry Mason. In eighty-two novels, six films, and nearly three hundred television episodes, Mason, a criminal-defense lawyer, took on seemingly guilty clients and proved their innocence. In the magazine, Gardner, who had practiced law before turning to writing, attempted to do something similar—except that there his “clients” were real people, already convicted and behind bars. All of them met the same criteria: they were impoverished, they insisted that they were blameless, they were serving life sentences for serious crimes, and they had exhausted their legal options. Gardner called his column “The Court of Last Resort.” To help investigate his cases, Gardner assembled a committee of crime experts, including a private detective, a handwriting analyst, a former prison warden, and a homicide specialist with degrees in both medicine and law. They examined dozens of cases between September of 1948 and October of 1958, ranging from an African-American sentenced to die for killing a Virginia police officer after a car chase—even though he didn’t know how to drive—to a nine-fingered convict serving time for the strangling death of a victim whose neck bore ten finger marks.