Hollywood Looks at the News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earth-11 Jumpchain Yes, This Is Just for Waifus

Earth-11 Jumpchain Yes, this is just for waifus This is a world of superhumans and aliens, one that may seem very familiar at first. However, this isn’t the normal world of DC Comics. No, this is one of its parallel dimensions, one where everybody is an opposite-gender reflection of their mainline counterparts. It’s largely the same besides that one difference, so the events that happened in the primary universe are likely to have happened here as well. The battle between good and evil continues on as it always does, on Earth, in space, and in other dimensions. Superwoman, Batwoman, Wonder Man, and the rest of the Justice League fight to protect the Earth from both from it’s own internal crime and corruption and from extraterrestrial threats. The Guardians of the Universe head the Green Lantern Corps to police the 3800 sectors of outer space, of which Kylie Rayner is one of the premier members. On New Genesis and Apokolips in the Fourth World, Highmother and Darkseid, the Black Queen vie for power, never quite breaking from their ancient stalemate. You receive 1000 CP to make your place in this world. You can purchase special abilities, equipment, superpowers, and friends to help you out on your adventures. Continuity You can start at any date within your chosen continuity. Golden Age The original timeline, beginning in 1938 with the first adventure of Superwoman. Before long she was joined by Batwoman, Wonder Man, and the Justice Society of America. The JSA is the primary superhero team of this Earth, comprised of the Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkwoman, Dr. -

Fact Or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News

FACT OR FICTION: HOLLYWOOD LOOKS AT THE NEWS Loren Ghiglione Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University Joe Saltzman Director of the IJPC, associate dean, and professor of journalism USC Annenberg School for Communication Curators “Hollywood Looks at the News: the Image of the Journalist in Film and Television” exhibit Newseum, Washington D.C. 2005 “Listen to me. Print that story, you’re a dead man.” “It’s not just me anymore. You’d have to stop every newspaper in the country now and you’re not big enough for that job. People like you have tried it before with bullets, prison, censorship. As long as even one newspaper will print the truth, you’re finished.” “Hey, Hutcheson, that noise, what’s that racket?” “That’s the press, baby. The press. And there’s nothing you can do about it. Nothing.” Mobster threatening Hutcheson, managing editor of the Day and the editor’s response in Deadline U.S.A. (1952) “You left the camera and you went to help him…why didn’t you take the camera if you were going to be so humane?” “…because I can’t hold a camera and help somebody at the same time. “Yes, and by not having your camera, you lost footage that nobody else would have had. You see, you have to make a decision whether you are going to be part of the story or whether you’re going to be there to record the story.” Max Brackett, veteran television reporter, to neophyte producer-technician Laurie in Mad City (1997) An editor risks his life to expose crime and print the truth. -

New Bebe Winans Musical 'BORN for THIS', Kathleen Turner and More Among Arena Stage's 2016-17 Lineup

broadwayworld.com http://www.broadwayworld.com/article/New-BeBe-Winans-Musical-BORN-FOR-THIS-Kathleen-Turner-and-More-Among-Arena-Stages- 2016-17-Lineup-20160215 New BeBe Winans Musical 'BORN FOR THIS', Kathleen Turner and More Among Arena Stage's 2016-17 Lineup by BWW News Desk Arena Stage just announced an exciting, starry 2016/17 season, which will showcase the theater's mission of American voices and artists. Spurred by its role as one of the seven originating theaters of D.C.'s Women's Voices Theater Festival, Arena Stage has embraced a commitment to inclusion with a season featuring seven titles by women, six playwrights of color and five female directors. On assembling the lineup Smith shares, "Arena has such a smart and diverse audience, so it is always a challenge to ensure everyone is energized. This season we leaned into that challenge and are welcoming a host of extremely talented artists both returning and new. This season is a celebration of Arena's broad shoulders, from our Lillian Hellman Festival, a Lorraine Hansberry classic and the gold-standard musical to world-premiere political dramas, a comedy and a new musical. The Mead Center was designed to have these different audiences unite in our flowing lobby, and I'm eager to experience this throughout our dynamic season." The season kicks off in July with the original world-premiere musical Born for This: The BeBe Winans Story by six- time Grammy Award winner BeBe Winans and veteran Arena Stage playwright/director Charles Randolph-Wright. Featuring new music by BeBe, the musical chronicles the early days of his career with sister CeCe and will star their niece and nephew, siblings Deborah Joy Winans and Juan Winans. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Jack London's Superman: the Objectification of His Life and Times

Jack London's superman: the objectification of his life and times Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kerstiens, Eugene J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:49:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319012 JACK LONDON'S SUPERMAN: THE OBJECTIFICATION OF HIS LIFE AND TIMES by Eugene J. Kerstiens A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1952 Approved: 7 / ^ ^ Director of Thesis date r TABLE OF OOHTEHTB - : ; : ■ ; ; : . ' . : ' _ pag® IHfRODUOTIOS a » 0 0 o o o » , » » * o a c o 0 0 * * o I FiRT I : PHYSICAL FORGES Section I 2 T M Fzontiez Spirit in- Amerioa 0 - <, 4 Section II s The lew Territories „,< . > = 0,> «, o< 11 Section III? The lew Front!@3?s Romance and ' Individualism * 0.00 0 0 = 0 0 0 13 ; Section IV g Jack London? Ohild of the lew ■ ■ '■ Frontier * . , o » ' <, . * , . * , 15 PART II: IDE0DY1AMI0S Section I : Darwinian Survival Values 0 0 0<, 0 33 Section II : Materialistic Monism . , <, » „= „ 0 41 Section III: Racism 0« « „ , * , . » , « , o 54 Section IV % Bietsschean Power Values = = <, , » 60 eoiOLDsioi o 0 , •0 o 0 0. 0o oa. = oo v 0o0 . ?e BiBLIOSRAPHY 0 0 0 o © © © ©© ©© 0 © © © ©© © ©© © S3 li: fi% O A €> Ft . -

2021 Conference Program (Draft)

Midwest Popular Culture Association and Midwest American Culture Association Annual Conference Thursday, October 7 – Sunday, October 10, 2021 MPCA/ACA website: http://www.mpcaaca.org #mpca21 Executive Secretary: Malynnda Johnson, Communication, Indiana State University, [email protected] Conference Coordinator: Lori Scharenbroich, Crosslake, MN, [email protected] Webmaster: Matthew Kneller, Communication, Aurora University, [email protected] Program Book Editors: [email protected] Jesse Schlotterbeck, Denison University Kathleen Turner, Ledgerwood, Vice-Chair, Lincoln University Pamela Wicks, Chair, Aurora University 1 PANELS AND PRESENTATIONS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7 TBD FRIDAY, OCTOBER 8 Friday 9:00 a.m. – 12:15 p.m. Manufacturing Registration/Exhibits Friday 1:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m. Manufacturing Registration/Exhibits Friday 9:00 a.m. – 10:30 a.m. 1101 Friday, 9:00-10:30 Agriculture Public Relations Contributions to 2021 Corona Vaccine Distribution in Popular Culture/ Beer 1 Advertising and Public Relations/Beer Culture “Covid-19 Vaccinations Enter Popular Culture Through Effective Public Relations Storytelling,” Patrick Karle, Independent Scholar, [email protected] “Effectively Engaging Generation Z,” Mark Beal, “Beer-Infused Czech Adaptations: Jiří Menzel’s Films and Bohumil Hrabal’s Prose,” Tanya Silverman, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Michigan, [email protected] “Community Memory: “Local” Brews and Hyperlocal History,” Josh Sopiarz, University Library, Governors State University, -

Oscar Host Ellen Degeneres Is Ready to Dance Cuaron's Oscar Nod

lifestyle SUNDAY, MARCH 2, 2014 Pharrell, U2, Idina Menzel rock Oscar rehearsals aving the nation’s No 1 song does not exempt an artist from Oscar rehearsals. Pharrell Williams ran through his Hcatchy hit “Happy” more than half a dozen times Friday in preparation for the Oscar telecast. He even shared the spotlight with a spate of stars: Jamie Foxx, Brad Pitt and Kate Hudson showed up to rehearse while he was on stage. All I care about is the fun,” Williams said to Hudson, who boogied in the audience as he practiced his dance-heavy number. A choir of high-school students and 20 professional dancers accompany his colorful performance. Also rehearsing Friday: Broadway star Idina Menzel, who’s set to sing “Let It Go” from animated film nominee “Frozen”; U2, which is nominated for its song from the Mandela movie, “Ordinary Love”; and rocker Karen O, who is nominated for “The Moon Song” from best-picture nominee “Her.” Menzel was awed by the technology that allowed the Oscar orchestra, playing off- site at the Capitol Records building, to coordinate with her live at the Dolby Theatre. “Hi, Bill, can you hear me?” she said into the microphone at conductor William Ross, whom she could see on a monitor from inside the theater. “I’m trying to get that telepathic vibe with you because I’m alone up here and this is my first time (on the Oscars). “You look very handsome,” she added. Karen O, front woman of the rock band Yeah Yeah Yeah’s, took notes from director Spike Jonze as she practiced her performance, “The Moon Song” from his best-picture nominee, “Her.” “Spike just asked me to hold the mic a little bit lower, so I need a little more level,” she told a sound engineer. -

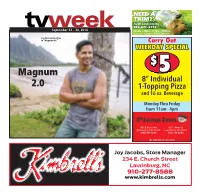

Magnum P.I.” Carry out Weekdaymanager’S Spespecialcial $ 2 Medium 2-Topping Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5And 16Each Oz

NEED A TRIM? AJW Landscaping 910-271-3777 September 22 - 28, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching Licensed – Insured – FREE Estimates 00941084 Jay Hernandez stars in “Magnum P.I.” Carry Out WEEKDAYMANAGEr’s SPESPECIALCIAL $ 2 MEDIUM 2-TOPPING Magnum Pizzas5 2.0 8” Individual $1-Topping99 Pizza 5and 16EACH oz. Beverage (AdditionalMonday toppings $1.40Thru each) Friday from 11am - 4pm 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, September 22, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Back to the well: ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to television with CBS reboot By Kenneth Andeel er One,” 2018) in the role of Higgins, dependence on sexual tension in TV Media the straight woman to Magnum’s the new formula. That will ultimate- wild card, and fellow Americans ly come down to the skill and re- ame the most famous mustache Zachary Knighton (“Happy End- straint of the writing staff, however, Nto ever grace a TV screen. You ings”) and Stephen Hill (“Board- and there’s no inherent reason the have 10 seconds to deduce the an- walk Empire”) as Rick and TC, close new dynamic can’t be as engrossing swer, and should you fail, a shadowy friends of Magnum’s from his mili- as its prototype was. cabal of drug-dealing, bank-rob- tary past. There will be other notable cam- bing, helicopter-hijacking racketeers The pilot for the new series was eos, though. -

Rourke, Daniel. 2019. the Practice of Posthumanism: Five Paradigmatic Figures for Human Mutation

Rourke, Daniel. 2019. The Practice of Posthumanism: Five Paradigmatic Figures for Human Mutation. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/26601/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] The Practice of Posthumanism: Five Paradigmatic Figures for Human Mutation Daniel Rourke Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted in fulfilment of a PhD in Art 2019 0 Declaration of Authorship I, Daniel Rourke, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. 14th January 2019 1 Acknowledgements With special thanks to Edgar Schmitz for being a great mentor and friend. Thanks also to Andrea Phillips, Yve Lomax, John Chilver, Kristen Kreider, and Michael Newman for their support and guidance, as well as Sarah Kember and John Russell for their thorough examination of the thesis in December 2017. Love to Holly Pester and my family for their unwavering generosity and understanding. This thesis would not have been possible without the minds of Holly Pester, Kyoung Kim, Zara Dinnen, Rob Gallagher, Morehshin Allahyari, Maria Fusco, Adrian Rifkin, Rosa Menkman, Nick Briz, Linda Stupart, Michael Connor and countless others who have enriched my intellectual and creative life over the past years. -

Movielistings

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 25, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESDAY’S SATURDAY EVENING MAY 26, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING MAY 27, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Family Jewels Family Jewels Gene Simmons Family The First 48 Burned Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Flip This House Profit chal- Flip This House (TV G) Jackpot Diaries, Part 2 Profile of lottery winners from Flip This House Profit chal- 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E lenge. (TV G) (R) (R) Texas and California. (TVPG) (N) lenge. (TV G) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) Jewels (TV14) (R) corpse. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero.