Downloadable Copies of the Application Forms for Both Return and Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIPSTAFF Volume II Issue

WARREN COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION, INC. TIPSTAFF Volume II Issue Dear Sisters and Brothers of the Bar: It is with great enthusiasm that I welcome you to the 2020 Fall edition of the Tipstaff. It is my hope that you and your families are safe and healthy in these troubling times. In the midst of this pandemic and the hostile political environment, I believe that practices and activities, such as the Tipstaff which we are able to continue and enjoy from the past, are more important than ever. Since taking the reins in June, Kate and the Board have been working diligently to prepare for the upcoming year in a way and format that has never been done before. We were able to meet in person, with proper masks and semi- social distancing, on the lawn of Morgan & Co. in September. This event was enjoyed by all who attended as we were finally able to have a bit of normalcy and see each other in person. On October 29, 2020, Kate and Maria Nowotny arranged to have Attorney James Long present a CLE on the topic of the New York Shield Act, which was attended by 20 of our members. Maria and Kate are busy preparing a CLE for December discussing the re-opening of the courts to be presented by our local justices and judges and other court staff. Upon the idea of Judge Kershko, Kate and I have worked with the Legal Aid Society of Northeastern New York to partner in the presentation of a CLE for volunteer assistance to pro-se litigants in foreclosure actions. -

BLM 2010-11.Pdf

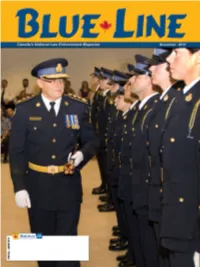

NOVEMBER 2010 2 BLUE LINE MAGAZINE November 2010 Volume 22 Number 9 Passing of the tipstaff: Former Ontario Provincial Police Com- missioner Julian Fantino, right, passes the tipstaff to newly appointed Commissioner Chris Lewis during the Change of Command ceremony in Toronto Tuesday, August 31, 2010. The tradition of passing the tipstaff has deep roots in policing and shows the authority of the Office of the Commissioner. The tipstaff used in this ceremony was designated as the Commissioner’s official symbol of authority by an Order in Council on October 13, 1969. It is engraved with of the Latin phrase Salus Populi which means “Let the good of the people be the supreme law.” See page 6. Features 6 Building upon the foundation New OPP Commisioner accepts the tipstaff 16 Empowering present and future challenges police leaders 8 Breaking the cycle 22 Dispelling myths and moving forward Vancouver Police undergo transformational change with PEACE 12 RCMP tested by Newfoundland hurricane Departments Case Law 38 Blue Links Advertisers Index 31 Charter breaches can be addressed at sentencing 35 Blue Pages 33 Search on arrest does not require urgency 18 Deep Blue 19 Dispatches 36, 37 Market Place 5 Publisher’s Commentary 28 Technology BLUEBLUE LLINEINE MMAGAZIAGAZINNEE 33 NOVEMBERNOVEMBER 20102010 NOVEMBER 2010 4 BLUE LINE MAGAZINE PUBLISHER’S COMMENTARY by Morley Lymburner Discretion is yours, sayeth the law Blue Line has always considered it impor- asked me to explain my rationale. I explained tant to provide our readers with plenty of case it was a new school zone that had just been law because modern police officers need to changed to a 40 km/h limit. -

Adams County Rules of Judicial Administration

ADAMS COUNTY RULES OF JUDICIAL ADMINISTRATION 1 - 99. Applicability 1. Offices To Which Rules Apply. The Rules adopted under this chapter shall apply to all offices in the Adams County court system unless the context indicates otherwise. Offices in the court system shall include the offices of Magisterial District Judges, the Clerk of Courts, Orphans' Court Division, Criminal and Miscellaneous Sections, and the Prothonotary. In some instances these rules will also apply to the Sheriff, Register of Wills and Recorder of Deeds. 2. Supplement To State Rules. Local rules are intended to supplement State rules and shall be read in context with those rules. In case of a conflict the rules adopted by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court shall prevail. 3. Citation To Local Rules. Local rules may be cited: Adams C.R.J.A. (number)-- Rules of Judicial Administration Adams C.Civ.R. (number)-- Rules of Civil Procedure Adams C.Crim.R. (number)-- Rules of Criminal Procedure Adams C.Juv.R. (number)-- Rules of Juvenile Court Procedure Adams C.O.R.(number)-- Rules of Orphans' Court Procedure They may also be cited as Local (R.J.A., Civ., Crim., Juv., O.C.) Rule (number). 100- 199. Administrative Matters 101. Court Calendar. The Court shall promulgate a court calendar annually. There shall be included therein no less than twelve {12) weeks set aside for criminal jury trials and no less than seven (7) weeks set aside for civil jury trials. The Prothonotary and Clerk shall prepare a list of cases scheduled for hearing, trial argument or other action at lease five (5) days prior to a specified calendar day and provide each judge presiding over such cases with a copy thereof. -

Allegheny County Council Committee on Budget And

ALLEGHENY COUNTY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ON BUDGET AND FINANCE 2015 BUDGET HEARING - - - BEFORE: John P. DeFazio - President Nicholas Futules - Vice President, District 7 Heather S. Heidelbaugh - Council-At-Large Tom Baker - District 1 Jan Rea - District 2 Ed Kress - District 3 Michael J. Finnerty - District 4 Sue Means - District 5 Robert J. Macey - District 9 Barbara Daly Danko - District 11 Allegheny County Courthouse Fourth Floor, Gold Room 436 Grant Street Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 Tuesday, October 28, 2014 - 5:00 p.m. SARGENT'S COURT REPORTING SERVICE, INC. 429 Forbes Avenue, Suite 1300 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 (412) 232-3882 FAX (412) 471-8733 IN ATTENDANCE: Jared Barker - Director of Legislative Services Walter Szymanski - Budget Director CHAIR FINNERTY: I'd like to call the meeting of Committee on Budget and Finance to order. This is a public hearing, and we're going to start with the Pledge of Allegiance; so would you please rise? (Pledge of Allegiance.) CHAIR FINNERTY: I'd just like to make a note of it. Today is the birthday of the Statue of Liberty, which was dedicated in 1886, over 120 years ago. And it's just been --- has been just restored in the last four or five years. MS. DANKO: Is this where I get to say it's my son's 25th birthday? And I'm here. CHAIR FINNERTY: Yeah, just raise your hand first. Okay. Walt? MR. SZYMANSKI: Yes, sir. CHAIR FINNERTY: We need somebody to take roll. MR. SZYMANSKI: Jared's not here. CHAIR FINNERTY: I guess Jared is not here. PRESIDENT DEFAZIO: Yeah, he'll be back. -

Crime (International Co-Operation) Act 2003

Source: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/32 Crime (International Co-operation) Act 2003 2003 CHAPTER 32 An Act to make provision for furthering co-operation with other countries in respect of criminal proceedings and investigations; to extend jurisdiction to deal with terrorist acts or threats outside the United Kingdom; to amend section 5 of the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981 and make corresponding provision in relation to Scotland; and for connected purposes. [30th October 2003] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART 1 MUTUAL ASSISTANCE IN CRIMINAL MATTERS CHAPTER 1 MUTUAL SERVICE OF PROCESS ETC. Service of overseas process in the UK 1Service of overseas process (1)The power conferred by subsection (3) is exercisable where the Secretary of State receives any process or other document to which this section applies from the government of, or other authority in, a country outside the United Kingdom, together with a request for the process or document to be served on a person in the United Kingdom. (2)This section applies— (a)to any process issued or made in that country for the purposes of criminal proceedings, (b)to any document issued or made by an administrative authority in that country in administrative proceedings, (c)to any process issued or made for the purposes of any proceedings on an appeal before a court in that country against a decision in administrative proceedings, (d)to any document issued or made by an authority in that country for the purposes of clemency proceedings. -

Court Administration Systems

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of key characteristics of COURT ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS Presented to the Canadian Judicial Council Administration of Justice Committee Administrative Efficiency in Trial and Appeal Courts Sub-Committee By Karim Benyekhlef Cléa Iavarone-Turcotte Nicolas Vermeys Université de Montréal Centre de recherche en droit public July 6th, 2011 © Canadian Judicial Council Catalogue Number JU14-24/2013E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-21994-3 Available from: Canadian Judicial Council Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0W8 (613) 288-1566 (613) 288-1575 (facsimile) and at: www.cjc-ccm.gc.ca FOREWORD | iii Foreword In 2006, the Canadian Judicial Council published a report entitled Alternative Models of Court Administration. In exploring the trend towards governments granting greater administrative autonomy to the courts, the report offered seven different models present in a number of jurisdictions. In 2011 the Administration of Justice Committee of Council commissioned a research study which would present a comparison of key characteristics of court administrative systems against those models in common law countries including Australia, England and Wales, New Zealand, North Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and Scotland. Key to this comparative analysis was the collection of legislation, memoranda of understanding and other forms of written agreements between the Judiciary and the Executive. They outline which level of government is responsible for certain or all aspects of court administration. The report consists of two documents. Presented here is the first part, namely, a comparative analysis building on the seven models presented in the 2006 report and further analysing how each of the selected jurisdictions advances their work according to six specific characteristics of court administration. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3. -

6328 Supplement to the London Gazette, Sth June 1968

6328 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, STH JUNE 1968 Harold Ambrose TOLHURST. For services to Basil Ebenezer HENDERSON, Welfare Officer, amateur sport. Central Housing and Planning Authority. For Arthur UPJOHN, Honorary Secretary, United services to the community of St. Kitts. Charities Fund. Miss Myrtle Mercedes WOODS. For voluntary social services in St. Kitts. STATE OF VICTORIA James Athonasus Daniel MASON, Steward Ronald Edward BLOOD, Captain, Upwey Rural Government House, St. Lucia. Fire Brigade. John Henry COSTAR. For services with Corps of Commissionaires. HOME OFFICE William John COX. For services to the Yarra WHITEHALL, LONDON, S.W.I Bend Park Trust. 8th June 1968 Colin James Henderson DRIFE, Lately Regional Secretary, Central Council Rural Fire Brigades THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on Association. the occasion of the Celebration of Her Majesty's Percy Alan GRAY, Deputy Chief Officer, Urban Birthday, to approve the award of the Queen's and Rural Fire Brigades. Police Medal for Distinguished Service to the Alan Charles HARDY, D.F.C., Group Officer, undermentioned: Mansfield Rural Fire Brigade. Queen's Police Medal William John JONES, Communications Officer, Moorooduc Rural Fire Brigade. ENGLAND AND WALES Lois, Mrs. KELLY, Radio Operator, Upwey and John Andrew McKAY, C.B.E., Her Majesty's Dandenong Ranges Fire Brigades Group. Inspector of Constabulary. William Herbert KYME, Member, State Service Robert WALTON, Chief Constable, Kingston- Concert Orchestra. upon-Hull City Police. Alexander William John McPHEE, Tipstaff to. Thomas Gwilym MORRIS, Chief Constable, Chief Justice. Cardiff City Police. Andrew O'BRIEN, Curator of the Gardens at David HOLDSWORTH, Deputy Chief Con- Government House, Melbourne. -

Twentieth Annual Report 1984-85

Scottish Law Commission (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 98) TWENTIETH ANNUALREPORT 1984-85 Laid before Parliament by the Lord Advocate under Section 3(3) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 20th November 1985 EDINBURGH HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE £4.90 net 20 The Scottish Law Commission was set up by section2of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law of Scotland. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Lord Maxwell, Chairman, Mr. R. D. D. Bertram, W.S., Dr. E. M. Clive, Mr. J. Murray, Q.C., Sheriff C. G. B. Nicholson, Q.C. The Secretary of the Commission is Mr. R. Eadie. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. ISBN 0 10 202086 8 SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 15TH JUNE 1985 To: The Right Honourable the Lord Cameron of Lochbroom, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate In accordance with section 3(3) as read with section 6(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, as amended,' we have the honour to submit this the Twentieth Annual Report of the Scottish Law Commission. (Signed) PETER MAXWELL, Chairman R. D. D. BERTRAM E. M. CLIVE JOHN MURRAY GORDON NICHOLSON R. EADIE, Secretary 2 September 1985 'Transfer of Functions (Secretary of State and Lord Advocate) Order 1972 (S.I. 1972, No. 2002). ... B 111 TWENTIETH ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Paragraph Page PREFACE . ix PART I GENERAL SURVEY OF THE PAST YEAR . 1.1 1 Our report on diligence and debtor protection . 1.1 1 Reports and consultative documents published . -

Fourteenth Report: Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 211) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 140) STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty April 1993 LONDON: HMSO E17.85 net Cm 2176 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Brooke, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge, Q.C. Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon. Its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Davidson, Chairman .. Dr E.M. Clive Professor P.N. Love, C.B.E. Sheriff I.D.Macphail, Q.C. Mr W.A. Nimmo Smith, Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr K.F. Barclay. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. .. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate. In pursuance of section 3(l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, we have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

Attending Court Supporting Members & Clients

ATTENDING COURT SUPPORTING MEMBERS & CLIENTS Courts and Tribunals have measures in place to conduct proceedings without the need for attending The Bar Association continues to actively monitor COVID-19 where possible, to respond to the developing COVID-19 pandemic. The Association is in constant contact developments and impacts on the Courts. Protecting the with the Courts and Tribunals. Click on the links below to jump to the latest information received about: health, safety and interests of members, while continuing to promote the administration of justice and serve the public The Supreme Court of New South Wales good, is our priority at this difficult time. The Land and Environment Court of New South Wales The District Court of New South Wales We are consistently updating our website and this point-in- The Local Court of New South Wales time resource as information comes to hand. However, The Children’s Court of NSW please always double-check the latest Court resources NSW Coroners Court directly as developments are changing quickly at this time NCAT and do not make any assumptions regarding your case NSW Industrial Relations Commission without first doing so. Workers Compensation Commission High Court of Australia Federal Court of Australia Key contacts Family Court of Australia & Federal Circuit Court of Australia Administrative Appeals Tribunal For the latest health information, please visit: Fair Work Commission Copyright Tribunal of Australia Australian Government, Department of Health – Alternative Dispute Resolution -

Information Document of October 2006

ENLÈVEMENT INTERNATIONAL D’ENFANTS INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUCTION Doc. d’information No 1 Information Document No 1 octobre / October 2006 L’EXÉCUTION DES DÉCISIONS FONDÉES SUR LA CONVENTION DE LA HAYE DE 1980 - UNE ÉTUDE EMPIRIQUE - par le Professeur Nigel Lowe, Samantha Patterson et Katarina Horosova Centre for International Family Law Studies, Faculté de droit de Cardiff, Université de Cardiff * * * ENFORCEMENT OF ORDERS MADE UNDER THE 1980 CONVENTION - AN EMPIRICAL STUDY- COMMISSIONED BY THE PERMANENT BUREAU AND SPONSORED BY THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR MISSING AND EXPLOITED CHILDREN By Professor Nigel Lowe, Samantha Patterson and Katarina Horosova Centre for International Family Law Studies, Cardiff Law School, Cardiff University Document d’information No 1 d’octobre 2006 à l’intention de la Cinquième réunion de la Commission spéciale sur le fonctionnement de la Convention de La Haye du 25 octobre 1980 sur les aspects civils de l’enlèvement international d’enfants (La Haye, 30 octobre – 9 novembre 2006) Information Document No 1 of October 2006 for the attention of the Fifth meeting of the Special Commission to review the operation of the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (The Hague, 30 October – 9 November 2006) Permanent Bureau | Bureau Permanent 6, Scheveningseweg 2517 KT The Hague | La Haye The Netherlands | Pays-Bas telephone | téléphone +31 (70) 363 3303 fax | télécopieur +31 (70) 360 4867 e-mail | courriel [email protected] website | site internet http://www.hcch.net