Exhibition Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

Richard Marsh's the Beetle (1897): Popular Fiction in Late-Victorian Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Vuohelainen, M. (2006). Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): A Late-Victorian Popular Novel. Working With English: medieval and modern language, literature and drama, 2(1), pp. 89-100. City Research Online Original citation: Vuohelainen, M. (2006). Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): A Late-Victorian Popular Novel. Working With English: medieval and modern language, literature and drama, 2(1), pp. 89-100. Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16325/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897): a late-Victorian popular novel by Minna Vuohelainen Birkbeck, University of London This paper deals with the publication history and popular appeal of a novel which, when first published in 1897, was characterised by contemporary readers and reviewers as “surprising and ingenious”, “weird”, “thrilling”, “really exciting”, “full of mystery” and “extremely powerful”. -

Thje Story Jpajpjer Cojljljector N:.��1�:1�:�.4

THJE STORY JPAJPJER COJLJLJECTOR N:.��1�:1�:�.4 ···················································································· ···················································································· Research on Modern "Comics" HERE Is Buying Guidance investigators compared the num on almost everything today ber of beats of a comic on a T and the "comic paper" is window sill, before the paper no exception. The boys of became useless. One of the boys Form 2J at Wakefield Cathedral had the use of a fish and chip Secondary School in England shop, where resistance to grease, have put the modern "comic" salt, and vinegar was measured. under the microscope. Their At first I thought that these findings have been published in tests were something entirely Mitre, the school magazine. new, but on examining some of Five boys of thirteen years did the old comics in my collection the research out of school hours, I see that these, too, have ap and most thoroughly did they parently been used for fly-swat go to work. They nominated as ting, and from the food-stains the best comic one which they on some of them they have also found not only best to read, but been tested as table-cloths! also the best for holding fish and I still have in my possession a chips, for fly-swatting, and for frantic letter from a postal mem fire-lighting! ber of the Northern Section The winning comic-unfortu [Old Boys' Book Club] library nately the name is not given in telling me that his wife had lit the report-took 66 minutes, 38 the fire with a Magnet from the seconds to read, against 9 min Secret Society series. -

THE STOR Y Rarjer

THE STORy rArJER JAl\.LARY 1954 COLLECTOR No. 51 :: Vol. 3 6th Chri,tma' J,,ue, The Magner, i'o. 305, December 13, 191 "l From the Editor's NOTEBOOK HAVE Volume I, the first 26 name pictured in The Srory Paper issues, of the early Harms Collet!or No. 48, but the same I worth weekly paper for publisher, Rrett), a "large num· women, Forger-Me-Nor, which ber" of S11rpris�s, Plucks, Union was founded, I judge - for the Jacks, Marwls, and True Blues cover-pages are missing-late in were offereJ at one shilling for 1891. In No. 12, issued probably 48, post free to any address. Un in January 1892, there is mention like Forgec-Me-Nors in 1892, these of a letter from a member of papers must have been consi The Forget-Me-Not Club. ln the dered of little value in 1901. words of the Editress (as she What a difference today! calls herself): IF The Amalgamated Press A member of the Clul> tt•rites IO had issued our favorite papers inform me rha1 she inserted an ad in volumes, after the manner of vertisement in E x change and Mart, Chums in its earlier years, there offering Rider Haggard's "Jess" and would doubtless he a more Longfellow's poems for a copy of plentiful supply of Magnets and No. 1 of Forget-Me-Not, l>ut she Gems and the rest today. They did not receive an offer. This speaks did not even make any great 1'0lumes for 1he value of the earl: prndicc of providing covers for numbers of Forger-Me-Not. -

Examine the Presentation of Crime and Transgression in Any Two Modernist Texts

Ayling page 1 Examine the presentation of crime and transgression in any two modernist texts I often think of those lines of old Goethe: Schade dass die Natur nur einen Mensch aus dir schuf, 1 Denn zum würdigen Mann war und zum Schelmen der Stoff. Nature, alas, made only one being out of you, Although there was material for a good man and a rogue.2 Sherlock Holmes applies these words to himself at the end of The Sign of the Four. In this essay, I first demonstrate how Holmes represents transgression, and I examine how being presented with a transgressive hero alters our attitudes towards transgression. I look at the differing ways in which characters in The Sign of the Four and A Scandal in Bohemia3 present crime and I attempt to put this in the context of how crime can be presented. Watson charitably remarks of Holmes that he "had observed that a small vanity underlay [his] companion's quiet and didactic manner"4. It is closer to arrogance. "I abhor the dull routine of existence,"5 Holmes decries, evidently believing that his personal abilities elevate him above having to endure the mundanities of life. Holmes is misogynistic: "Women are never to be entirely trusted - not the best of them"6. He is self-centred: he responds to news of his friend's 1 1 Arthur Conan Doyle; The Sign of the Four; first edition; Christopher Roden; (Oxford; Oxford University Press; 1993); page 119. 2 2 Ibid.; p.137. 3 3 Quotations from A Scandal in Bohemia taken from: Arthur Conan Doyle; The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes; (London; George Newnes Ltd.; 1895). -

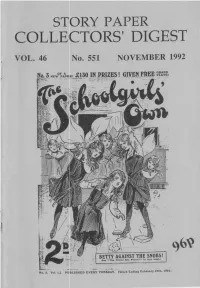

Colle1ctors' Digest

S PRY PAPER COLLE 1CTORS' DIGEST VOL. 46 No. 551 NOVEMBER 1992 BETTY AGAINST THE SNOBSI 8M u TIH Fri ... d atie ,..,,.,,d I'' II\ thi• IHllt.) - • ..a.... - No, 3, Vol . I ,) PU81. I SH£0 £VER Y TUESDAY, [Wnk End•nll f'~b,.,&ry l&th, 191 1, ONCORPORATING NORMAN SHAW) ROBIN OSBORNE, 84 BELVEDERE ROAD, LONDON SE 19 2HZ PHONE (BETWEEN 11 A.M . • 10 P.M.) 081-771 0541 Hi People, Varied selection of goodies on offer this month:- J. Many loose issues of TRIUMPH in basically very good condition (some staple rust) £3. each. 2. Round volume of TRIUMPH Jan-June 1938 £80. 3. GEM . bound volumes· all unifonn · 581. 620 (29/3 · 27.12.19) £110 621 . 646 (Jan· June 1920) £ 80 647 • 672 (July · Dec 1920) £ 80 4. 2 Volumes of MAGNET uniformly bound:- October 1938 - March 1939 £ 60 April 1939 - September 1939 £ 60 (or the pair for £100) 5. SWIFT - Vol. 7, Nos.1-53 & Vol. 5 Nos.l-52, both bound in single volumes £50 each. Many loose issues also available at £1 each - please enquire. 6. ROBIN - Vol.5, Nos. 1-52, bound in one volume £30. Many loose issues available of this title and other pre-school papers like PLA YHOUR, BIMBO, PIPPIN etc. at 50p each (substantial discounts for quantity), please enquire. 7. EAGLE - many issues of this popular paper. including some complete unbound volumes at the following rates: Vol. 1-10, £2 each, and Vol. 11 and subsequent at £1 each. Please advise requirements. 8. 2000 A.D. -

Pre-Immigration Screening for Pulmonary Tuberculosis

2 Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn MH, Waterhouse LM, 6 Sadeghnejad A, Karmaus W, Arshad SH, Matthews SM, Holgate ST, Arshad SH. Characterization of Kurukulaaratchy R, Huebner M, Ewart S. IL-13 gene wheezing phenotypes in the first 10 years of life. Clin Exp polymorphisms modify the effect of exposure to tobacco Allergy 2003; 33: 573–578. smoke on persistent wheeze and asthma of childhood. A 3 Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Matthews S, Holgate ST, Arshad SH. longitudinal study. Respir Res 2008; 9: 2. Predicting persistent disease among children who wheeze 7 Bottema RWB, Reijmerink NE, Kerkhof M, et al. Interleukin during early life. Eur Respir J 2003; 22: 767–771. 13, CD14, pet and tobacco smoke influence atopy in three 4 Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Matthews S, Arshad SH. Does envir- Dutch cohorts: the allergenic study. Eur Respir J 2008; 32: onment mediate earlier onset of the persistent childhood 593–602. asthma phenotype? Pediatrics 2004; 113: 345–350. 8 Conan Doyle A. The Return of Sherlock Holmes. London, 5 Arshad SH, Hide DW. Effects of environmental factors on George Newnes Ltd, 1905. the development of allergic disorders in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992; 90: 235–241. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00149408 Pre-immigration screening for pulmonary tuberculosis From the authors: and the clinical diagnosis prevails. Thus, in most cases, this is the immigrant’s first life-time exposure to radiography. The authors thank BHUNIYA [1] for his interesting comments on our article published in the European Respiratory Journal (ERJ) Most industrialised countries use a combination of CXR and [2]. Tuberculosis (TB) screening policies are influenced by the TST to screen immigrants originating from high-TB-incidence structure of the national TB programme, the existing financial countries [12–15]. -

Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry

Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry Howard Cox University of Worcester Paper prepared for the European Business History Association Annual Conference, Bergen, Norway, 21-23 August 2008. This is a working draft and should not be cited without first obtaining the consent of the author. Professor Howard Cox Worcester Business School University of Worcester Henwick Grove Worcester WR2 6AJ UK Tel: +44 (0)1905 855400 e-mail: [email protected] 1 Mass Circulation Periodicals and the Harmsworth Legacy in the British Popular Magazine Industry Howard Cox University of Worcester Introduction This paper reviews some of the main developments in Britain’s popular magazine industry between the early 1880s and the mid 1960s. The role of the main protagonists is outlined, including the firms developed by George Newnes, Arthur Pearson, Edward Hulton, William and Gomer Berry, William Odhams and Roy Thomson. Particular emphasis is given to the activities of three members of the Harmsworth dynasty, of whom it could be said played the leading role in developing the general character of the industry during this period. In 1890s Alfred Harmsworth and his brother Harold, later Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere respectively, created a publishing empire which they consolidated in 1902 through the formation of the £1.3 million Amalgamated Press (Dilnot, 1925: 35). During the course of the first half of the twentieth century, Amalgamated Press held the position of Britain’s leading popular magazine publisher, although the company itself was sold by Harold Harmsworth in 1926 to the Berry brothers in order to help pay the death duties on Alfred Harmsworth’s estate. -

David Cooper John Ayres the Babbacombe Cliff Railway

By David Cooper & John Ayres For and on behalf of the The Babbacombe Cliff Railway CIC 2 THE HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE BABBACOMBE CLIFF RAILWAY By David Cooper & John Ayres For and on behalf of the The Babbacombe Cliff Railway CIC 3 CONTENTS TECHNICAL DETAILS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 CHRONOLOGY .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6-7 SIR GEORGE NEWNES AND THE EARLY OFFER .. .. .. 8-9 GEORGE CROYDON MARKS .. .. .. .. .. .. 10-12 THE 1926 INSTALLATION .. .. .. .. .. .. 13-16 THE 1951 & 55 REFURBISHMENTS .. .. .. .. .. 16 1955-1993 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 THE 1993 REFURBISHMENT .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 THE 2005/6 REFURBISHMENT .. .. .. .. .. 19-23 THE TALCA BELL .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 24 BIBLIOGRAPHY .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 THE AUTHORS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 26-27 4 TECHNICAL DETAILS Track Length: 720 ft Gauge: 5 ft 10 in Rise: 256 ft Speed: 500 feet per minute Rated Load: 40 passengers per car Cover picture: The track limit switches 5 CHRONOLOGY 1890 George Newnes & George Croydon Marks team up. George Newnes offered to build a cliff railway at Babbacombe which was rejected. 1910 Sir George Newnes dies and is buried in Lynton 1922 George Croydon Marks consulted by Torquay Tramway Company about building a cliff railway at Babbacombe 1923 Torquay Tramway Company announce plans to build a cliff railway. Babbacombe Cliff Light Railway Order issued by Parliament 1924 Building work starts in the December. 1926 Cliff railway opens on 1st April Babbacombe Cliff Light Railway Statutory Rules & Orders Act issued by Parliament 1929 George Croydon Marks is given a peerage and becomes Baron Marks of Woolwich 1935 Torquay Corporation take over control of the lift from the Tramway Company on 13th March 1938 George Croydon Marks dies in Bournemouth 6 1941 Closed down due to war time restrictions 1951 Reopens on 29th June 1955 Babbacombe Cliff Railway (Amendment) Order issued Car frames & cars replaced 1993 Modernisation programme – cliff railway closes. -

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers Palmers Lane Aylsham Two Day Books & Ephemera Sale Norwich NR11 6JA United Kingdom Started Aug 25, 2016 10:30Am BST

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers Palmers Lane Aylsham Two Day Books & Ephemera Sale Norwich NR11 6JA United Kingdom Started Aug 25, 2016 10:30am BST Lot Description J R R TOLKIEN: THE HOBBIT OR THERE AND BACK AGAIN, illustrated David Wenzel, Forestville, Eclipse Books, 1990, limited 1 edition de-luxe (600), signed by the illustrator and numbered, original pictorial cloth gilt, dust wrapper, original silk lined solander box gilt J R R TOLKIEN AND DONALD SWANN: THE ROAD GOES EVER ON - A SONG CYCLE, London 1968, 1st edition, original paper 2 covered boards, dust wrapper J R R TOLKIEN: THE ADVENTURES OF TOM BOMBADIL, illustrated Pauline Baynes, London, 1962, 1st edition, original pictorial 3 paper-covered boards, dust wrapper J R R TOLKIEN: THE LORD OF THE RINGS, illustrated Alan Lee, North Ryde, Harpercollins, Australia, 1991, centenary limited edition 4 (200) numbered and signed by the illustrator, 50 coloured plates plus seven maps (of which one double page) as called for, original quarter blue morocco silvered, all edg ...[more] J R R TOLKIEN, 3 titles: THE LORD OF THE RINGS, London 1969, 1st India paper de-luxe edition, 1st impression, 3 maps (of which 2 5 folding) as called for, original decorative black cloth gilt and silvered (lacks slip case); THE HOBBIT OR THERE AND BACK AGAIN, 1986 de-luxe edition, 4th impression, orig ...[more] J R R TOLKIEN: THE HOBBIT OR THERE AND BACK AGAIN, 1976, 1st de-luxe edition, coloured frontis plus 12 coloured plates plus 6 two double page maps as called for, original decorative black cloth gilt and silvered, -

Submarine Escape Apparatus

SUBMARINE ESCAPE APPARATUS PRINCIPAL CONTENTS THE BEGINNING OF FLYING SIMPLE HYGROMETER STUDIES IN ELECTRICITY MAKING AN ELECTRIC HEATER HARDENING PLASTER CASTINGS LIGHT PUNCHING MACHINE FACTS ABOUT GENEVA STEEL PASSENGER HAULING MODEL LOCO.CYCLIST SECTION When / wantaCL/AIturn to TERRY'S (the 5,o people) I go to TERRY'S for all kinds of CLIPS-steel, bronze, stainless, etc. When I want a clip made to specification, Terry's Research Department is a big help in the matter of design (Terry's with 96 years' experience should know a thing or two !) 7.77:7737rrrr, Nos. 8o and Si come from 1" to z" from stock. No.300,anexcep- tionally good drawing board clip, costs 5/- a doz.(inc. p.t.)from stock. Want to know all about springs? Here is the most comprehensive text - book on springs in existence. No. 80 Post free to/6 No. 81 No. 300 Sole Makers:HERBERT TERRY & SONS, LTD., REDDITCH London Birmingham Manchester IIT4F October, 1951 NEWNES PRACTICAL MECHANICS 1 A COMPLETE TRAIN SET FOR YOUR BOY The Prince Charles train set is not just a toy, but a real " live" scale model that will give years of joy to its owner. Areal " live " BASSETT-LOWKE train set. The finest model train ever offered (clockwork or electric). A layout of track, an engine and its wagons or coaches bought now at a moderate cost, grows in time by the addition of " extras " into an enthralling miniature railway system that never loses its fascination. .. Acompleteclockworkset,inc. PurchaseTax. A modern style of station exactly in scale with Bassett- Price£7.17.6 Lowke stock No. -

The Creation, Reception and Perpetuation of the Sherlock Holmes Phenomenon, 1887 - 1930

The Creation, Reception and Perpetuation of the Sherlock Holmes Phenomenon, 1887 - 1930 by Katherine Mary Wisser A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina June, 2000 Approved by: _______________________ Advisor 2 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge several people who have contributed to the completion of this project. Elizabeth Chenault and Imre Kalanyos at the Rare Book Collection were instrumental in helping me with the texts in their collection. Their patience and professionalism cannot be overstated. Special thanks go to my advisor, Dr. Jerry D. Saye for supporting and encouraging me throughout the program. This work is dedicated to my husband, whose steadfast love and support keeps me going. Katherine Mary Wisser Chapel Hill, NC 2000 Katherine Mary Wisser. “The Creation Perception and Perpetuation of the Sherlock Holmes Phenomenon, 1887 – 1930.” A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. June, 2000. pages. Advisor: Jerry D. Saye This study examines the role of author, reader and publisher in the creation of the Sherlock Holmes legacy. Each entity participated in the inculcation of this cultural phenomenon. This includes Conan Doyle’s creation of the character and his perception of that creation, the context of the stories as seen through the reader’s eye, and the publishers’ own actions as intermediary and as agent. The examination of 160 Holmes texts at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Wilson Library Rare Book Collection provides insights into the manipulation of the book as object during Conan Doyle’s life, including such elements as cover design, advertisements and illustrations.