This Is Our Music V.2-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 19451970

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Society and Culture Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 19451970 Williams, KA http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/4429 10.1558/jazz.v7i1.113 Jazz Research Journal Equinox Publishing All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. [JRJ 7.1 (2013) 113-131] (print) ISSN 1753-8637 doi:10.1558/jazz.v7i1.113 (online) ISSN 1753-8645 Post-World War II Jazz in Britain: Venues and Values 1945–1970 Katherine Williams Department of Music, Plymouth University [email protected] Abstract This article explores the ways in which jazz was presented and mediated through venue in post-World War II London. During this period, jazz was presented in a variety of ways in different venues, on four of which I focus: New Orleans-style jazz commonly performed for the same audiences in Rhythm Clubs and in concert halls (as shown by George Webb’s Dixielanders at the Red Barn public house and the King’s Hall); clubs hosting different styles of jazz on different nights of the week that brought in different audiences (such as the 100 Club on Oxford Street); clubs with a fixed stylistic ideology that changed venue, taking a regular fan base and musicians to different locations (such as Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club); and jazz in theatres (such as the Little Theatre Club and Mike West- brook’s compositions for performance in the Mermaid Theatre). -

Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz, 1960-1974

Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz, 1960-1974 Duncan Heining Sheffield and Bristol, CT: Equinox, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-84553-405-9 (HB) Katherine Williams University of Plymouth [email protected] In Trad Dads, Dirty Boppers and Free Fusioneers, British Jazz 1960–1974, Duncan Heining has made a significant contribution to the available literature on British jazz. His effort is particularly valuable for addressing a period that is largely neglected; although the same period is covered from a fusion perspective in Ian Carr’s Music Outside (1973, rev. 2008) and Stuart Nicholson’s Jazz-Rock (1998), to my knowledge Heining has provided the first full-length study of the period from a jazz angle. Trad Dads provides a wealth of information, and is packed densely with facts and anecdotes, many of which he gained through a series of original interviews with prominent musicians and organizers, including Chris Barber, Barbara Thompson, Barry Guy, Gill Alexander and Bill Ashton. Throughout the monograph, he makes a case for the unique identity and sound of British jazz. The timeframe he has picked is appropriate for this observation, for there are several homegrown artists on the scene who have been influenced by the musicians around them, rather than just visiting US musicians (examples include Jon Hiseman and Graham Bond). Heining divides his study thematically rather than chronologically, using race, class, gender and political stance as themes. Chapters 1 to 3 set the scene in Britain during this period, which has the dual purpose of providing useful background information and an extended introduction. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

JOHN SURMAN Title: FLASHPOINT: NDR JAZZ WORKSHOP – APRIL '69 (Cuneiform Rune 315-316)

Bio information: JOHN SURMAN Title: FLASHPOINT: NDR JAZZ WORKSHOP – APRIL '69 (Cuneiform Rune 315-316) Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [Press & world radio]; radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [North American radio] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ One of Europe’s foremost jazz musicians, John Surman is a masterful improvisor, composer, and multi-instrumentalist (baritone and soprano sax, bass clarinet, and synthesizers/electronics). For 45 years, he has been a major force, producing a prodigious and creative body of work that expands beyond jazz. Surman’s extensive discography as a leader and a side man numbers more than 100 recordings to date. Surman has worked with dozens of prominent artists worldwide, including John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, Dave Holland, Miroslav Vitous, Jack DeJohnette, Terje Rypdal, Weather Report, Karin Krog, Bill Frisell, Paul Motian and many more. Surman is probably most popularly known for his longstanding association with the German label ECM, who began releasing Surman’s recordings in 1979. Surman has won numerous jazz polls and awards and a number of important commissions. Every period of his career is filled with highlights, which is why Cuneiform is exceedingly proud to release for the first time ever this amazing document of the late 60s 'Brit-jazz' scene. Born in Tavistock, in England, Surman discovered music as a child, singing as soprano soloist in a Plymouth-area choir. He later bought a second- hand clarinet, took lessons from a Royal Marine Band clarinetist, and began playing traditional Dixieland jazz at local jazz clubs. -

NJA British Jazz Timeline with Pics(Rev3) 11.06.19

British Jazz Timeline Pre-1900 – In the beginning The music to become known as ‘jazz’ is generally thought to have been conceived in America during the second half of the nineteenth century by African-Americans who combined their work songs, melodies, spirituals and rhythms with European music and instruments – a process that accelerated after the abolition of slavery in 1865. Black entertainment was already a reality, however, before this evolution had taken place and in 1873 the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an Afro- American a cappella ensemble, came to the UK on a fundraising tour during which they were asked to sing for Queen Victoria. The Fisk Singers were followed into Britain by a wide variety of Afro-American presentations such as minstrel shows and full-scale revues, a pattern that continued into the early twentieth century. [The Fisk Jubilee Singers c1890s © Fisk University] 1900s – The ragtime era Ragtime, a new style of syncopated popular music, was published as sheet music from the late 1890s for dance and theatre orchestras in the USA, and the availability of printed music for the piano (as well as player-piano rolls) encouraged American – and later British – enthusiasts to explore the style for themselves. Early rags like Charles Johnson’s ‘Dill Pickles’ and George Botsford’s ‘Black and White Rag’ were widely performed by parlour-pianists. Ragtime became a principal musical force in American and British popular culture (notably after the publication of Irving Berlin’s popular song ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ in 1911 and the show Hullo, Ragtime! staged at the London Hippodrome the following year) and it was a central influence on the development of jazz. -

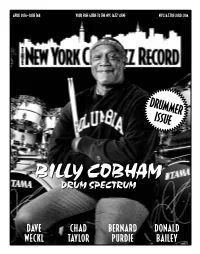

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Philip Freeman: Running the Voodoo Down - the Electric Music of Miles Davis Pdf

FREE PHILIP FREEMAN: RUNNING THE VOODOO DOWN - THE ELECTRIC MUSIC OF MILES DAVIS PDF Philip Freeman | 242 pages | 16 Dec 2005 | BACKBEAT BOOKS | 9780879308285 | English | San Francisco, United States Jazz Fusion, Jazz, Books | Barnes & Noble® From the early New York apprenticeship with Charlie Parker, through Davis's drug addiction of the early s, to the years during which he signed with Columbia and recorded masterpieces with John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, and Cannonball Adderly, Carr sheds new light on Davis's life and career. His reclusive period is explored with firsthand accounts of his descent back into Philip Freeman: Running the Voodoo Down - the Electric Music of Miles Davis as is his dramatic return to life and music. This new work Ian Carr was born in Dumfries, Scotland on April 21, He received a degree in English and a teaching certificate from King's College. While there, he began playing the trumpet. He wrote for several jazz publications, contributed to several jazz reference books and was a consultant for television documentaries about Miles Davis and Keith Jarrett. He died from complications after pneumonia and a series of mini-strokes on February 25, at the age of Miles Davis : The Definitive Biography. Ian Carr. Ian Carr's book is the perfect counterpoint and corrective to Miles Davis's own brilliant but vitriolic autobiography, providing a balanced portrait of one of the undisputed cultural icons of the 20th century. Carr has talked with the people who knew the man and his music best; and for this edition, updated since Davis's death, he has conducted new interviews with a number of jazz greats, including Ron Carter, Max Roach, and John Scofield. -

Ian Carr out of the Long Dark/Old Heartland Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ian Carr Out Of The Long Dark/Old Heartland mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Out Of The Long Dark/Old Heartland Country: UK Released: 1998 Style: Jazz-Rock, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1437 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1100 mb WMA version RAR size: 1460 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 723 Other Formats: MP4 AIFF MOD ASF DXD XM MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits 1-1 Gone With The Weed 1-2 Lady Bountiful Solar Wind 1-3 Composed By – Geoff CastlePercussion [Guest] – Chris Fletcher 1-4 Selina 1-5 Out Of The Long Dark (Conception) 1-6 Sassy (American Girl) 1-7 Simply This (The Human Condition) 1-8 Black Ballad (Ecce Domina) 1-9 For Liam 2-1 Northumbrian Sketches Part 1: Open Country 2-2 Northumbrian Sketches Part 2: Interiors 2-3 Northumbrian Sketches Part 3: Disjunctive Boogie 2-4 Northumbrian Sketches Part 4: Spirit Of Place 2-5 Full Fathom Five 2-6 Old Heartland 2-7 Things Past Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – MMC Recordings Ltd. Copyright (c) – BGO Records Licensed To – EMI Records Ltd. Licensed From – EMI Special Markets Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Mixed At – Abbey Road Studios Mastered At – Abbey Road Studios Credits Art Direction, Design – Chris Archer (tracks: 1-1 to 1-9), Cream (tracks: 1-1 to 1-9) Bass – Dill Katz (tracks: 2-5 to 2-7) Cello – Mark Davies (tracks: 2-1 to 2-4), Rachael Maguire* (tracks: 2-1 to 2-4), Robert Woolard* (tracks: 2-1 to 2-4) Composed By – Ian Carr Design – Bill Smith Studio (tracks: 2-1 to 2-7) Directed By – Ian Carr (tracks: -

From Birth to Death of Cool

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-2009 From Birth to Death of Cool Brandon Theriault Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Theriault, Brandon, "From Birth to Death of Cool" (2009). Honors Theses. 1657. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/1657 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM BIRTH TO DEATH OF COOL by Brandon Theriault An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Lee Honors College of Western Michigan University April, 2009 INTRODUCTION "Miles Davis was a bad dude. He was one of the baddest men in jazz... baddest jazzman ever." -Alvin Jones. Who is Alvin Jones? Alvin Jones is the man I just met outside of the Bernhard Center on Western Michigan University's campus in Kalamzoo, MI. I have been laboring over my honors thesis for months now; I am approaching its completion and was at a loss for a way to start the piece. As Alvin Jones stumbled up to me panhandling for a cigarette I could not help but notice his physical similarity to Miles. He looked to be approaching 65, white whiskers sparsely covering his face and making appearances throughout his eyebrows. He was slender, taller than average, and had exaggerated facial features; large luminous eyes, long eyelashes and high cheekbones. -

ISSUE 16 ° May 2008 Swinging Shepherd!

Ne w s L E T T e R Editor: Dave Gelly ISSUE 16 ° May 2008 swinging shepherd! Digby Fairweather introduces and wonderfully generous Dave Shepherd, distinguished human being. So, rather than interview guest at this year’s a formal ’interview’, our Summer Jazz Event (see box Loughton meeting will be right) in July. simply a whatever-comes-next chat between old friends. Welcoming Dave Shepherd Dave’s regular designation as to the interview chair at our ’Britain’s Benny Goodman’ is far Summer Jazz Event 2008 is one more than a handy publicity tag. of the most exciting things to When pianist Teddy Wilson, a happen to the NJA - and to me – in many a moon. Because lifelong colleague of the ‘King of since Artie Shaw gave up writ- Swing’, began visiting Britain in ing books and joined his princi- the 1970s, his automatic clar- pal rival, Benny Goodman, in inet partner for international touring and recording was Dave Editors Note: Saturday 26th July NATIONAL JAZZ ARCHIVE JAZZ NATIONAL some (literally) heavenly clar- inet section, Dave is, quite Shepherd, who by then had 1.30–4.30pm at Loughton Methodist probably, the greatest swing already been playing for more Church Tickets at £10 can be obtained clarinettist in the world. than a quarter of a century. from David Nathan at the Archive and He’s much more fun to inter- After post-war beginnings cheques to be made payable to view, too. Whereas Artie (as I amid the flourishing east- National Jazz Archive. know from experience) made London Dixieland fraternity, he his interrogator feel like a joined drummer Joe Daniels in feather in a wind-tunnel, and 1951, then graduated summa Benny, by all accounts, never said cum laude to the band of his much at all, Dave has a fund of hero Freddy Randall in 1954. -

Downloads, the Bandleader Composed the Entire Every Musician Was a Multimedia Artist,” He Said

AUGUST 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.