Fallwinter2020newsletter 11.19.20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

105-107 and 109 Washington Street Image Appendix

105-107 and 109 washington street image appendix Image 1: The western coastline of Colonial Manhattan was located at present-day Greenwich Street. Source: http://www.trinitywallstreet.org/files/pages/history/timeline-1705.pdf 1 Image 2: An 1867 map of 105 and 107 Washington Street depicts two buildings, both with front and rear structures. Source: Dripps, Mathew. Plan of New York City. c. 1867. Plate 02. Image 3: Manhattan: Washington Street - Rector Street. c. April 1911. The image depicts the two early tenements on the lot that were replaced in 1926 by the Downtown Community House. Source: New York Public Library Digital Gallery, Digital ID: 724079f. 2 Image 4: Cover for 1920 Bowling Green Neighborhood Association’s report. Location of the Association at the time was 45 West Street. Source: Bowling Green Neighborhood Association. Report on Six Months Experimental Restaurant for Undernourished Children. New York: Bowling Green Neighborhood Association, 1920, p. 1. 3 Image 5: A few members of the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association, West Street near the Battery. Source: Brown, Henry Collins. Valentine's City of New York: A Guidebook. New York: The Chauncey Hold Company, 1920. p. 44. Image 6: Former home of William H. Childs in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Fordmadoxfraud 4 Image 7: A John F. Jackson-designed YMCA in Rochester, NY. Source: "Central YMCA, Rochester, N.Y. John F. Jackson." Architectural Record. January 1919. p. 426. Image 8: Exterior sketch of Jersey City Y.M.C.A., by John F. Jackson. Source: “Office Sketches in Pencil by John F. -

Napoli, Mary Ann Haick Dinapoli, Syrian, from Downtown Brooklyn, Whose Family Had Come from Syria

INDIVIDUAL INTERVIEW The Reminiscences of Joseph Svehlak © 2021 New York Preservation Archive Project PREFACE The following oral history is the result of a recorded interview with Joseph Svehlak conducted by Interviewer Sarah Dziedzic on February 1, 2021. This interview is part of the New York Preservation Archive’s Project’s collection of individual oral history interviews. The reader is asked to bear in mind that s/he is reading a verbatim transcript of the spoken word, with minor editing by Joseph Svehlak, rather than written prose. The views expressed in this oral history interview do not necessarily reflect the views of the New York Preservation Archive Project. Joseph Svehlak was born in Sunset Park, Brooklyn––or Old Bay Ridge––to immigrant parents of Moravian-Czech descent, who initially resided on the Lower West Side of Manhattan before relocating to Brooklyn. Svehlak is a founding member of the Friends of the Lower West Side, and has worked to bring recognition to the diverse history of the neighborhood and to secure Landmark status for the area’s three remaining buildings. Purchasing his “first old house” in Sunset Park in 1970, Svehlak became involved with community activism to address a lack of city services and languishing of community activities the neighborhood. With a few neighbors, he established a block association in 1971, and was a founding member in the mid-‘70s of the neighborhood-wide Sunset Park Restoration Committee, which organized house tours and coordinated resources for homeowners to restore their old homes, among other community activities. He eventually got his real estate license to help recruit homebuyers to Sunset Park, and started doing walking tours of the neighborhood––in part because he didn’t own a car. -

ASG, Past, Present, and Future: Architectural Specialty Group at 25

May 2013 Vol. 38, No. 3 Inside From the Executive Director 2 AIC News 4 ASG, Past, Present, and Future: Annual Meeting 5 Architectural Specialty Group FAIC News 5 at 25 JAIC News 7 by George Wheeler, Frances Gale, Frank Matero, and Joshua Freedland (editor) Allied Organizations 7 Introduction The Architectural Specialty Group (ASG) is celebrating its twenty-fifth Health & Safety 8 anniversary as a group within AIC. To mark this milestone, three leaders were asked to reflect about the architectural conservation field. The Sustainable Conservation Practice 10 selected group has been involved in educating architectural conserva- COLUMN tors and promoting the field of architectural conservation, and each has New Materials and Research 11 SPONSORED played a role in the development of ASG. Each was asked to indepen- BY A SG dently discuss architectural conservation and education today in the New Publications 12 context of past history and future possibilities. People 13 The need to teach future architectural conservators the philosophical framework for making conservation treatment and interpretation decisions remains clear, as it has Worth Noting 13 since the founding of the professional field in the 1960s. New architectural materials and styles, documentation techniques, and research methodologies threaten to fragment Grants & Fellowships 13 the architectural conservation field into specialists who function more as technicians than professionals. This struggle is neither new nor specific to architectural conservation; Specialty Group Columns -

HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION the Preservationist

KANKAKEE COUNTY HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION The Preservationist Volume 1, Issue 1 Summer 2015 Special points of interest: Kankakee county Preser- Kankakee County Preservation Commission vation Commission Re- ceives Grant from IHPA Receives Grant from IHPA Community Foundation Grant The Kankakee County with a roadmap for the residents and also to bring French-Canadian Heritage Historic Preservation county’s future preserva- public awareness of the Corridor Commission (KCHPC), as tion activity. An effective importance of protecting a Certified Local Govern- action plan will establish and maintaining those re- French-Canadians of Kankakee County ment, applied for and re- goals set forth by our sources. We seek to en- ceived a $19,950 Certified community and will organ- courage enthusiasm and What Does a Historic Preservation Commission Local Government (CLG) ize preservation activities support for preservation do? 2015 Matching Grant in a logical sequence that to grow in a positive way. from the Illinois Historic can be achieved in a rea- A preservation plan is KCHPC seeks to form a Steering Committee Preservation Agency sonable time period. The also an economic develop- (IHPA). The federally plan will be a public out- ment tool. Businesses and Kankakee County Historic funded grant will be used reach tool for the Com- individual property own- Preservation Commission to finance a Comprehen- mission, involving the pub- ers are attracted to com- Working together: City of sive Kankakee County lic in the planning process. munities when they value Kankakee and Kankakee County Historic Preservation Plan Public meetings will be the characteristics found developed to encourage held in communities in communities with the preservation of the throughout Kankakee strong preservation pro- county’s historic re- County, in an attempt to grams. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Preservationist Summer 06.Indd

Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission the Preservationist Summer 2006 Blockhouse Point Conservation Park and the Camp at Muddy Branch by Don Housley, Vivian Eicke and James Sorensen Branch was preoccupied with stemming the raids of Confederate partisan units led by Colonel John S. A team of archaeologists and volunteers from Mosby and Lieutenant Elijah Viers White. Montgomery County Park and Planning has begun excavations at Blockhouse Point, a conservation The most significant event associated with park owned by M-NCPPC. Documentary research Muddy Branch and the blockhouses was the result and a new non-invasive archaeological technique of General Early’s attack on Washington in July of – gradiometric surveying – are helping to uncover 1862. With Early’s forces on the doorstep of D.C. the fascinating history of the site. and all the Union forces recalled to the defense of the Capital, Mosby took advantage by burning At the beginning of the Civil War, the the temporarily-vacated blockhouses along the nation’s capital and its approaches were virtually Potomac. On July 12, Mosby found the camps at unprotected. As a result of Confederate raids across Blockhouse Point and Muddy Branch abandoned the Potomac and the Union disaster at First Bull and burned their equipment and supplies. Run, Washington became one of the most fortified U.S. Army 1st Lieutenant cities in the world. In addition to forts ringing Gradiometric mapping of shovel test pits on the Robert Gould Shaw the city, blockhouses were built to serve as early site of the soldiers’ camp at Blockhouse Point in described Muddy Branch as warning stations along the Upper Potomac to the fall of 2005 showed the location of disturbances “the worst camp we have protect the canal and the river crossings. -

Quantifying Visitor Impact and Material Degradation at George Washington's Mount Vernon Laurel Lynne Bartlett Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2013 Quantifying Visitor Impact and Material Degradation at George Washington's Mount Vernon Laurel Lynne Bartlett Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Bartlett, Laurel Lynne, "Quantifying Visitor Impact and Material Degradation at George Washington's Mount Vernon" (2013). All Theses. 1599. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUANTIFYING VISITOR IMPACT AND MATERIAL DEGRADATION AT GEORGE WASHINGTON’S MOUNT VERNON A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Schools of Clemson University and the College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Laurel Lynne Bartlett May 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Carter L. Hudgins, Committee Chair Frances Ford Ralph Muldrow Elizabeth Ryan ABSTRACT Over one million visitors per year traverse the visitor path through George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon. Increased visitation has tested the limits of the architectural materials and created the single most threatening source of degradation. While the history of Mount Vernon is dotted with attempts to mitigate damage caused by visitors, scientific analysis of the dynamic impacts to the historic fabric is needed to preserve the integrity of the preeminent national house museum. The following thesis presents a holistic analysis of visitor impact and material degradation occurring at Mount Vernon. -

Bpc Community Center Task Force

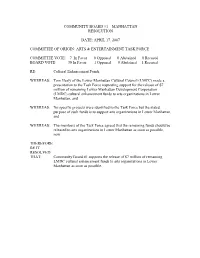

COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: APRIL 17, 2007 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT TASK FORCE COMMITTEE VOTE: 7 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused BOARD VOTE: 39 In Favor 1 Opposed 0 Abstained 1 Recused RE: Cultural Enhancement Funds WHEREAS: Tom Healy of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) made a presentation to the Task Force requesting support for the release of $7 million of remaining Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) cultural enhancement funds to arts organizations in Lower Manhattan, and WHEREAS: No specific projects were identified to the Task Force but the stated purpose of such funds is to support arts organizations in Lower Manhattan, and WHEREAS: The members of the Task Force agreed that the remaining funds should be released to arts organizations in Lower Manhattan as soon as possible, now THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT: Community Board #1 supports the release of $7 million of remaining LMDC cultural enhancement funds to arts organizations in Lower Manhattan as soon as possible. COMMUNITY BOARD #1 – MANHATTAN RESOLUTION DATE: APRIL 17, 2007 COMMITTEE OF ORIGIN: ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT TASK FORCE COMMITTEE VOTE: 7 In Favor 0 Opposed 0 Abstained 0 Recused BOARD VOTE: 26 In Favor 6 Opposed 4 Abstained 4 Recused RE: Community Enhancement Funds WHEREAS: Eric Deutsch of the Downtown Alliance (Alliance) and Tom Healy of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) made a presentation to the Task Force on the proposed use of Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) community enhancement -

Vacancy Announcement

VACANCY ANNOUNCEMENT Coastal Environmental Law Parks & Wildlife Resources Protection Enforcement Historic Resources Resources Division Division Division Division Division Vacant Position Listing Please click on the Job Title – Location to learn more about the advertised vacant position Georgia County & Major City Map ........................................................................... 2 Applicant Information ............................................................................................ 3 Central Office Vacancies ......................................................................................... 4 Accountant 2 – Fulton County ................................................................................... 4 Financial Operations Generalist 2 – Fulton County ....................................................... 5 Administrative Assistant 1 – Fulton County ................................................................. 7 Parks and Historic Resources Division Vacancies ................................................... 8 Park / Historic Site Assistant Manager – Franklin County .............................................. 8 Curator / Preservationist 1 – Harris County ............................................................... 10 Administrative Assistant 3 – White County ................................................................ 11 Food Service Specialist 2- Elbert County ................................................................... 12 Parks Maintenance Technician 3 – Morgan County .................................................... -

PROPERTY DISPOSITION Health and Hospitals Corporation

SUPPLEMENT TO THE CITY RECORD THE CITY COUNCIL-STATED MEETING OF WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 7, 2009 28 PAGES THE CITY RECORD THE CITY RECORD Official Journal of The City of New York U.S.P.S.0114-660 Printed on paper containing 40% post-consumer material VOLUME CXXXVI NUMBER 55 MONDAY, MARCH 23, 2009 PRICE $4.00 PROPERTY DISPOSITION Health and Hospitals Corporation . .1023 Sanitation . .1024 TABLE OF CONTENTS Citywide Administrative Services . .1022 Materials Management . .1023 Agency Chief Contracting Officer . .1024 Homeless Services . .1023 PUBLIC HEARINGS & MEETINGS Division of Municipal Supply Services 1022 School Construction Authority . .1024 Office of Contracts and Procurement . .1023 Police . .1022 Contract Administration . .1025 Board Meetings . .1013 Housing Authority . .1023 Auction . .1022 Bureau of Contracts Services . .1025 Administration for Children’s Services .1013 Purchasing Division . .1024 PROCUREMENT Youth and Community Development . .1025 Housing Preservation and Development 1024 City University . .1013 Administration for Children’s Services .1022 AGENCY RULES Human Resources Administration . .1024 Citywide Administrative Services . .1025 City Planning Commission . .1013 Citywide Administrative Services . .1023 Labor Relations . .1024 SPECIAL MATERIALS Division of Municipal Supply Services 1023 Employees’ Retirement System . .1021 Office of the Mayor . .1024 Tax Commission . .1026 Vendor Lists . .1023 Landmarks Preservation Commission . .1021 Criminal Justice Coordinator’s Office .1024 Changes in Personnel . .1052 Design and Construction . .1023 Parks and Recreation . .1024 LATE NOTICES Transportation . .1022 Contract Section . .1023 Contract Administration . .1024 Criminal Justice Coordinator . .1052 Voter Assistance Commission . .1022 Environmental Protection . .1023 Revenue and Concessions . .1024 Economic Development Corporation . .1052 THE CITY RECORD MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, Mayor Contractor/Address 1. Brooklyn Perinatal Network, Inc. MARTHA K. -

Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Hoboken Historic District City of Hoboken, Hudson County, New Jersey

Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Hoboken Historic District City of Hoboken, Hudson County, New Jersey Final Report Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction and New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 April 26, 2019 Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Project number: DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 Hoboken Historic District Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Emily Paulus Everett Sophia Jones Daniel Eichinger Senior Preservation Planner Director of Historic Preservation Project Administrator Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 1 4/22/19 Draft revision Yes E. Everett Sr. Preservation Planner Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name 1 Yes NJ HPO 1 Yes City of Hoboken Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction AECOM Intensive-Level Architectural Survey of the Project number: DPMC Contract #: P1187-00 Hoboken Historic District Prepared for: State of New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Property Management and Construction Erin Frederickson, Project Manager New Jersey Historic Preservation Office Department of Environmental Protection Mail Code 501-04B PO Box 420 501 E State Street Trenton, NJ 08625 Prepared by: Emily Paulus Everett, AICP Senior Preservation Planner Samuel A. Pickard Historian Samantha Kuntz, AICP Preservation Planner AECOM 437 High Street Burlington NJ, 08016 -

A History of the Otis Elevator Company

www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Going Up! Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description Going Down! 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~182 1 LkiLooking BkBack 183~394 2 Reach for the Sky A History 395~608 3 Elevatoring of the 609~732 4 Escalating 733~790 5 Law of Gravity Otis Elevator Company 791~931 6 A Fair to Remember 932~1,100 7 Through the Years 1 2 Part 1 The Art of the Elevator Looking Back 3 4 “The history of the Otis Elevator Company is the history of the development of the Elisha Graves Otis was born in 1811 on a farm in Halifax, VT. elevator art. Since 1852, when Elisha Graves As a young man, he tried his hand at several careers – all Otis invented and demonstrated the first elevator ‘safety’ - a device to prevent an with limited success. In 1852, his luck changed when his elevator from falling if the hoisting rope employer; Bedstead Manufacturing Company, asked him to broke - the name Otis has been associated design a freight elevator. Determined to overcome a fatal with virtually every important development hazard in lift design (unsolved since its earliest days), Otis contributing to the usefulness and safety of invented a safety brake that would suspend the platform elevators…” RE: excerpt from 87 Years of Vertical Trans- safely within the shaft if a lifting rope broke suddenly. Thus portation with Otis Elevators (1940) was the world’s first “Safety Elevator” born. Left: Elisha Graves. Otis 5 6 © J.M. Syken 1 www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org “…new and excellent platform elevator, by Mr.