An Analysis of the 1990 Top Corporations in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upscale Research on Mini-Variety (Sari-Sari) Store Project

CARD, INC. UPSCALE RESEARCH ON MINI-VARIETY (SARI-SARI) STORE PROJECT FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Evelyn N. Leviste March 15, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. BACKGROUNDER 3 II. SURVEY RESULTS 4 III. ANALYSIS & RECOMMENDATIONS a. The Retail Industry (International) 12 b. The Retail Industry (Philippines) 14 c. The Philippine Retail Market Players 14 d. The Sari-Sari Store Business - Definition, Success Factors and Challenges 16 - Prospects 21 e. Opportunities for CARD Clients 27 ANNEXES A. CARD Upscale Research Design B. Area Selection Design C. Product Ranking: Top Ten Products D. Suppliers List: Top Ten Products CARD Upscale Research on Mini-Variety (Sari-Sari) Stores: Prepared by E. Leviste Page 2 of 30 CENTER FOR AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (CARD), INC. UPSCALE RESEARCH ON MINI-VARIETY (SARI-SARI) STORES I. BACKGROUNDER CARD, Inc. launched the “Hapinoy” Project in partnership with Microventures, Inc. on December 2006. This project focuses on the sari-sari store business with an aim to establish the biggest sari-sari store chain in the Philippines. Currently, there are seven lead stores and one thousand small stores that have signed up as retailers in the “Hapinoy” pilot areas in the CALABARZON1. Owners of these sari-sari stores are combination of CARD and non-CARD members. Based on the demand survey conducted by CARD on October 9-20, 2006, about 12% of CARD clients are engaging in the sari-sari store business and majority of these clients show high repayment rate. CARD sees the potential to provide its clients with an opportunity to increase their income through this project. -

Paylink Merchants 2005

LIST OF AFFILIATED MERCHANTS Count Merchant No. Legal Name DBA Name Address1 Address 2 City Area Code / Desc 1 181933 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ALABANG) TIERRA NUEVA SUBD. ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 2 1117761 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (BULACAN) IS PAVILIONS MEYCAUAYAN 58 - BULACAN 3 181834 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (CALOOCAN) RIZAL AVE. EXT. CALOOCAN CALOOCAN CITY 28 - CALOOCAN 4 1117167 WALTER MART STA ROSA, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (DASMARINAS) WALTERMART, KM 30 BO BUROL AGUINALDO DASMARINAS 59 - CAVITE 5 290288 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (ERMITA) 3/F ROBINSONS PLACE ERMITA MANILA 20 - MANILA 6 231852 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (EVER ORTIGA G/F EVER GOTESCO ORTIGAS AVE., STA. LUCIA, PASIG CITY PASIG CITY 25 - PASIG 7 231878 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (FARMER'S) FARMER'S PLAZA CUBAO QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 8 182485 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GALLERIA) ORTIGAS AVE., QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 9 182469 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (GREENHILLS) UNIMART SUPERMART GREENHILLS SAN JUAN, METRO MANILA SAN JUAN 23 - SAN JUAN 10 181917 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (HARRISON) 1ST FLR. HARRISON PLAZA COMML. VITO CRUZ, MALATE MANILA 20 - MANILA 11 182501 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (LAS PINAS) 269 ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD PAMPLONA LAS PINAS 32 - LAS PINAS 12 289397 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (METROPOLIS) G/F MANUELA METROPOLIS ALABANG MUNTINLUPA 33 - MUNTINLUPA 13 181875 ABENSON INCORPORATED ABENSON - PAYLINK (QUAD) QUAD I, MCC . MAKATI CITY 22 - MAKATI 14 181768 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SHERIDAN) 11 SHERIDAN ST., MANDALUYONG MANDALUYONG 24 - MANDALUYONG 15 181859 ABENSON, INC. ABENSON - PAYLINK (SM CITY) SM CITY NORTH EDSA QUEZON CITY QUEZON CITY 21 - QUEZON CITY 16 181784 ABENSON, INC. -

Study Report: Market Survey on the Philippines

“Market Research and Monitoring on the leather industry in selected Asian countries: China, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam” STUDY REPORT: MARKET SURVEY ON THE PHILIPPINES Contract n. ASI/B7-301/95/108-35 Account number ALA 95/25 This text has been drafted with the financial assistance of the Commission of the European Communities. The views expressed herein are those of Unione Nazionale Industria Conciaria and therefore in no way reflect the official opinion of the Commission. INDEX - Philippines SECTION A: COUNTRY REPORT 1. Political background 2. Economic background 3. Foreign trade 4. Commercial relations with Italy SECTION B: MARKET STUDY 1. Executive summary 2. Country regulations 2.1 Import and Export Activity 2.1.1 Policies on imports 2.1.2 Foreign exchange policies 2.1.3 Export development Act incentives 2.2 Foreign Investments 2.2.1 Regulation 2.2.2 Investment Priorities Plan (IPP) 2.3 Industrial Activities 2.3.1 Philippine Environmental laws 2.4 Customs Regulations 2.4.1 Import duties & taxes 2.4.2 Import documents 2.4.3 Pre shipment inspection 2.4.4 Basic export guidelines 2.4.5 Terms of payment 2.5 Distribution Channels 3. State of the Industry 3.1 Tanning Industry 3.1.1 Raw material supply and trade 3.1.2 Geographical location 3.1.3 Current situation of the industry 3.1.4 Current processing capability 3.1.5 Profile of major companies 3.1.6 Development plan of the industry 3.1.6.1 Hides and skins Improvement Program 3.1.6.2 Efforts to encourage closer business cooperation 3.1.6.3 Importation of hides/skins and finished leather -

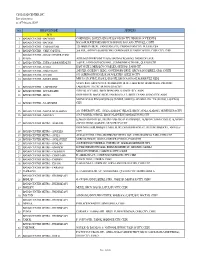

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of Partners As of February 2020*

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of partners as of February 2020* NO. BRANCH NAME ADDRESS BCO 1 BAYAD CENTER - BACOLOD COKIN BLDG. LOPEZ JAENA ST.,BACOLOD CITY, NEGROS OCCIDENTAL 2 BAYAD CENTER - BACOOR BACOOR BOULEVARD, BRGY. BAYANAN, BACOOR CITY HALL, CAVITE 3 BAYAD CENTER - CABANATUAN 720 MARILYN BLDG., SANGITAN ESTE, CABANATUAN CITY, NUEVA ECIJA 4 BAYAD CENTER - CEBU CAPITOL 2nd FLR., AVON PLAZA BUILDING, OSMENA BOULEVARD CAPITOL. CEBU CITY, CEBU BAYAD CENTER - DAVAO CENTER POINT 5 PLAZA ATRIUM CENTERPOINT PLAZA, MATINA CROSSING, DAVAO DEL SUR 6 BAYAD CENTER - EVER COMMONWEALTH 2ndFLR., EVER GOTESCO MALL, COMMONWEALTH AVE., QUEZON CITY 7 BAYAD CENTER - GATE2 EAST GATE 2, MERALCO COMPLEX, ORTIGAS, PASIG CITY 8 BAYAD CENTER - GMA CAVITE 2ND FLR. GGHHNC 1 BLDG., GOVERNORS DRVE, BRGY SAN GABRIEL, GMA, CAVITE 9 BAYAD CENTER - GULOD 873 QUIRINO HWAY,GULOD,NOVALICHES, QUEZON CITY 10 BAYAD CENTER - KASIGLAHAN MWCI.SAT.OFFICE, KASIGLAHAN VIL.,BRGY.SAN JOSE,RODRIGUEZ, RIZAL SPACE R-O5 GROUND FLR. REMBRANDT BLDG. LAKEFRONT BOARDWALK, PRESIDIO 11 BAYAD CENTER - LAKEFRONT LAKEFRONT, SUCAT, MUNTINLUPA CITY 12 BAYAD CENTER - LCC LEGAZPI 4TH FLR. LCC MALL, BRGY.DINAGAAN, LEGASPI CITY, ALBAY 13 BAYAD CENTER - LIGAO GROUND FLR. MA-VIC BLDG, SAN ROQUE ST., BRGY. DUNAO, LIGAO CITY, ALBAY MAYNILAD LAS PIÑAS BUSINESS CENTER, MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON UNO, LAS PIÑAS 14 BAYAD CENTER - M. ALVAREZ CITY 15 BAYAD CENTER - MAYNILAD ALABANG 201 UNIVERSITY AVE., AYALA ALABANG VILLAGE, BRGY. AYALA ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 16 BAYAD CENTER - MAYSILO 479-F MAYSILO CIRCLE, BRGY. PLAINVIEW, MANDALUYONG CITY LOWER GROUND FLR., METRO GAISANO SUPERMARKET, ALABANG TOWN CENTER, ALABANG- 17 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD, ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY GROUND FLOOR,MARQUEE MALL BLDG, DON BONIFACIO ST., PULUNG MARAGUL, ANGELES 18 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ANGELES CITY 19 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA AYALA CENTER, CEBU ARCHBISHOP REYES AVE., CEBU BUSINESS PARK, CEBU CITY 20 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA FELIZ MARCOS HI-WAY, LIGAYA, CORNER JP RIZAL, PASIG CITY 21 BAYAD CENTER METRO - BANILAD A.S FORTUNA CORNER H. -

Bayad Center Name Address

BAYAD CENTER NAME ADDRESS BAYAD CENTER - APEC LIGAO ALBAY POWER AND ENERGY CORP.(APEC), DUNAO, LIGAO BAYAD CENTER - APEC TABACO ALBAY POWER &ENERGY CORP,LLORENTE ST,KINALE,TABACO BAYAD CENTER - BACOLOD COKIN BLDG. LOPEZ JAENA ST.,BACOLOD CITY BAYAD CENTER - BACOOR BACOOR BOULEVARD BRGY. BAYANAN, BACOOR CITY HALL BAYAD CENTER - CABANATUAN 720 MARILYN BLDG., SANGITAN ESTE, CABANATUAN CITY BAYAD CENTER - CEBU CAPITOL 2/F AVON PLAZA BUILDING OSMENA BOULEVARD CAPITOL BAYAD CENTER - CITY OF SAN FERNANDO STALL 3 PUSO ITI AMIANAN BLDG., SEVILLA, CITY OF SAN FERNANDO, LA UNION BAYAD CENTER - DARAGA CORNER ARBOLEDA ST., RIZAL STREET, DARAGA, ALBAY BAYAD CENTER - DAVAO CENTER POINT PLAZA ATRIUM CENTERPOINT PLAZA, MATINA CROSSING BAYAD CENTER - EVER COMMONWEALTH 2ND FLOOR EVER GOTESCO MALL, COMMONWEALTH AVE., QUEZON CITY BAYAD CENTER - GATE2 EAST GATE 2 MERALCO COMPLEX ORTIGAS PASIG BAYAD CENTER - GMA CAVITE GOVERNORS DRVE, BRGY SAN GABRIEL GMA BAYAD CENTER - GULOD 873 QUIRINO HWAY,GULOD,NOVALICHES BAYAD CENTER - KASIGLAHAN MWCI.SAT.OFC KASIGLAHAN VIL.,BRGY.SN JOSE,RODRIGUE BAYAD CENTER - LAKEFRONT REMBRANDT BLDG.LKFRNT BRDWLK,PRESIDIO LKFRNT SUCAT BAYAD CENTER - LCC LEGAZPI 4F LCC MALL, DINAGAAN, LEGAZPI CITY BAYAD CENTER - M. ALVAREZ LAS PI?AS BUS AREA,MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE,TALON SINGKO VENTURE BUILDING, PRIME ST. COR. MARKET ST., MADRIGAL BUSINESS PARK, ALABANG, BAYAD CENTER - MAYNILAD ALABANG MUNTINLUPA CITY BAYAD CENTER - MAYSILO 479-F MAYSILO CIRCLE, BRGY. PLAINVIEW, MANDALUYONG BAYAD CENTER METRO - ALABANG ALABANG TOWN CENTER ALABANG-ZAPOTE ROAD ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY BAYAD CENTER METRO - ANGELES MARQUEE MALL BUILDING, DON BONIFACIO STREET PULUNG MARAGUL, ANGELES CITY BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA AYALA CENTER CEBU ARCHBISHOP REYES AVENUE CEBU BUSINESS PARK, CEBU CITY BAYAD CENTER METRO - BANILAD A.S FORTUNA CORNER H. -

Ma. Teresa Dueñas-Caparas

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Dueñas-Caparas, Ma. Teresa Working Paper State of Competition in the Wholesale and Retail Sector PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2005-05 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Dueñas-Caparas, Ma. Teresa (2005) : State of Competition in the Wholesale and Retail Sector, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2005-05, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127887 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas State of Competition in the Wholesale and Retail Sector Ma. -

Pre-Construction/Site Preparation

GROUND PENETRATING RADAR SURVEY (GPR) Ground Penetrating Radar GPR SURVEY USES OF GPR SURVEY: To Detect: To Conduct: • Underground Utilities • Archaeological Studies • Cavities and Voids • Buried Objects • Hidden Structures To Assist in: • Forensic Investigations • Pre-construction/Site Preparation Sample Findings: Rebars and underground utilities. DTI CERTIFICATE OF REGISTRATION BUSINESS PERMIT BIR CERTIFICATE OF REGISTRATION CURRICULUM VITAE OF GEOTECHNICAL / PILE TESTING CONSULTANTS (ENGR. RICHARD C. TAN, MSCE) (ENGR. SUNSHINE V. TAN, MSCE) CURRICULUM VITAE OF RICHARD C. TAN PERSONAL DATA Date of Birth June 28, 1959 Nationality Filipino Civil Status Married Business Address 103 Dunhill Street Fairview ParkSubdivision East Fairview, QuezonCity. Tel. No. 939-6368; 427-4940 E-mail:[email protected] Website:www.ages.ph Profession Geotechnical Engineer PRC License CivilEngineer Reg. No. 23248 November, 1980. PDA Testing Provider Advanced Level (Foundation QA Certif.) Foundation QA ID No. 6B51F7CA338 Language Proficiency English, Filipino, Chinese. EDUCATION Masters of Science in Civil Engineering ( MSCE ) Major in Soil Mechanics University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City 1983 Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering ( BSCE ) Mapua Institute of Technology Intramuros, Manila 1979 AWARDS AND HONORS 1st placer of the Philippine Board Examination for Civil Engineers given by the Professional Regulations Commission on May, 1980. Recipient of the Most Outstanding Performance in the Board Examination Award given by the Mapua Institute of Technology -

Prime Properties for Bidding ______

PRIME PROPERTIES FOR BIDDING _________________________________________ (1) Along Roxas Boulevard (Parañaque City) . IRC Mapalad Property . 4,038 sq.m. Minimum bid price : P278,622,000.00 _________________________________________ (2) Near The Mansion (Baguio City) . Hans Menzi Compound Property . 3,875.57 sq.m. Minimum bid price : P37,245,850.00 _________________________________________ Availability of Bid Documents: 19 March to 04 April 2012, IRC Building, 82 EDSA, Mandaluyong City Date of Sealed Public Bidding: 24 April 2012 Bidding Time: 10:00 a.m. for Hans Menzi Compound and 2:00 p.m. for Mapalad Property For particulars, call Ms. Alma M. Provido at tel. nos. 9079127 or 7256958 www.pcgg.gov.ph PCGG BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ANNEX "A" IRC MAPALAD PROPERTY PROPERTY LOCATION The property consists of four (4) contiguous parcels of land located on the eastern side of Roxas Boulevard and along the northern side of Librada Avelino Street, within Barangay Baclaran, Parañaque City. The site is about 400 meters from NAIA Road; about 1.5 kilometers south from EDSA; about one kilometer from the Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA); and approximately two kilometers from the SM Mall of Asia (MOA). LAND DATA The property herein identified as the IRC Mapalad Property contains an aggregate area of 4,038 square meters, more or less, technically identified as follows: Lot No. TCT No. Area (sq.m.) 1-A, Plan (LRC) Psd-727 010-2011001197 403 1-B, Plan (LRC) Psd-727 010-2011001200 714 46-B, Plan (LRC) Psd-726 010-2011001198 378 46-A, Plan (LRC) Psd-726 010-2011001199 2,543 4,038 sq.m. -

Philippines-USD-Payout-Locations.Pdf

Network Agent Name Agent Location Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City Province Postal Code Phone Code City Phone Number I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - BANGUE TORRIJOS STREET ZONE 5 BANGUED ZONE 5 BANGUED ABRA 2800 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC A BITO POBLACION ABUYOG 6510 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - AGOO L NATIONAL HIGHWAY SAN ANTONIO AGOO LA UNION 2504 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC. - P SO UBOS REAL ST. AJUY 5012 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - ALAMIN MARCOS AVE BRGY PALAMIS ALAMINOS CITY PANGASINAN I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC. - A 50 KINABRANAN KINABRANAN ZONE I (POB.) ALLEN SAMAR 6405 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC - AL MURAYAN POBLACION ALTAVAS 5616 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC DIGITAL PARADISE INC. - MARQUE 3RD LEVEL SPACE 3050 MARQUEE MALL ANGELES PAMPANGA 2009 HOZUM CORP 1226 CANDD MCARTHUR HIGHWAY NINOY AQUINO I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC ANGELE MARISOL ANGELES PAMPANGA 2009 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC DIGITAL PARADISE INC (NETOPIA) P OLIVEROS 3 CORNER G MASANGKAY ST G/F/F MARIKINA VALLEY CUPANG ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC COGEO SITIO KASAPI MARCOS HI WAY BAGONG NAYON ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC MASINA 195 MARCOS HIGHWAY MAYAMOT ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 SUMULONG MEMORIAL CIRCLE CIRCUMFERENTIAL RD CHRISTMAR I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. SAN ROQ VILL ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC APALIT MCARTHUR HIGHWAY BRGY SAMPALOC APALIT PAMPANGA 2016 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. -

State of Competition in the Wholesale and Retail Sector

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas State of Competition in the Wholesale and Retail Sector Ma. Teresa Dueñas-Caparas DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2005-05 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. March 2005 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph STATE OF COMPETITION IN THE WHOLESALE AND RETAIL SECTOR FINAL DRAFT Ma. Teresa Dueňas-Caparas March 2005 Table of Contents Introduction Section 1. Overview of the Philippine Distribution Sector ………………………………………….. 2 1.1 Main Distribution Sectors: Definition and Product ………………………………………… 3 1.2 Industry Profile ……………………………………………………………………………... 4 1.2.1 Number of Establishments …………………………………………………………. 4 1.2.2 Revenue/Sales ………………………………………………………………………. 5 1.2.3 Employment ………………………………………………………………………… 7 1.2.4 Gross Margin Ratio ………………………………………………………………… 9 1.3 Philippine Retailing: Added Features ……………………………………………………… 10 1.3.1 Economies of Scale in Store Operations …………………………………………… 10 1.3.2 Retailers and Centralized Distribution …………………………………………….