Some Real Mothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rogerzelazny

the collected $29 stories of “ Roger Zelazny was one of the collected stories of roger the collected stories of SF’s finest storytellers, a zelazny Roger Zelazny poet with an immense and Roger Zelazny 5 volume 5: nine black doves instinctive gift for language. volume five nine black Reading Zelazny is like doves nine black doves WINN Roger Zelazny wrote with a lyrical quality rarely found G dropping into a Mozart in science fiction—creating rousing adventures, intricate H © BETH “what-if?” stories, clever situations, and sweeping vistas in P string quartet as played which to play them out. Leavened with layers of allusion by Thelonious Monk.” PHOTOGRA and imagery, his diverse writing styles and breadth of — GREG BEAR subject matter brought him praise as a prose poet and a Roger Zelazny (1937–1995) reaffirmed his mastery of short Renaissance man. Zelazny’s vivid stories, especially his fiction during the 1980s with his release of a pair of Hugo-winning stories, his completion of the Dilvish series, and his creation of Volume 5: Nine Black Doves covers spectacular novellas, are classics in the field. Croyd Crenson for the Wild Cards shared world. the 1980s, when Zelazny’s mature Although he is best known for his 10-volume Amber During the interval covered by this volume, Zelazny began the second craft produced the Hugo-winning and series, his early novels Lord of Light and Creatures of Light five-book series in the Chronicles of Amber, starting with Trumps of Doom. He continued his serious study of martial arts and he created Nebula-nominated stories, “24 Views of and Darkness, and the Dilvish series, his shorter works a shared world of his own. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Academic Library Services East Carolina University Joyner Library • Greenville, NC 27858-4353 252-328-6514 Office• 252-328-6892 Fax

Academic Library Services East Carolina University Joyner Library • Greenville, NC 27858-4353 252-328-6514 office • 252-328-6892 fax Administrative Services and For immediate release on January 4, 2006. Office of the Director 328-6514 Archives J.Y. JOYNER LIBRARY ADDS LITERATURE OF THE FANTASTIC COLLECTION 328-0272 Building Operations Greenville, NC, January 4, 2006: The Special Collections Department at J.Y. Joyner Library on the campus of 328-4156 East Carolina University is pleased to announce the addition of the James and Virginia Schlobin Collection of Circulation/Reserve 328-6518 Literature of the Fantastic. Established in 2004 by Professor Roger C. Schlobin in of honor of his parents, the Library Development collection was created to serve the needs of students studying this genre of literature and to offer materials to aid 328-6514 scholars of fantastic literature. Fantastic literature includes fantasy readings, science fiction, gothic, horror fiction Documents/Microforms and can be characterized as being unusual or supernatural. 328-0238 Interlibrary Loan The Schlobin Collection is comprised of approximately one thousand titles, mostly science fiction and horror 328-6068 novels. Featured authors include Andre Norton, Michael Moorcock, Roger Zelazny, L. Sprague de Camp, Philip Music Library 328-6250 Jose Farmer and Charles de Lint, among others. The collection also includes literature for juvenile audiences and North Carolina Collection journals, most notably the . With hopes to increase the collection, 328-6601 new materials may be acquiredJournal through of the Fantastic gifts, purchases in the Arts, and Fantasy transfers. and Ariel Readers can access the printed materials Reference in this fantastic collection through the Joyner Library online catalog, located at www.lib.ecu.edu. -

Tolkien of the New Millenium NEIL GAIMAN: the J.R.R

NEIL GAIMAN: the J.R.R. Tolkien of the new millenium “My parents would frisk me before family events …. Because if they didn’t, then the book would be hidden inside some pocket … and as soon as whatever it was got under way I’d be found in a corner. That was who I was … I was the kid with the book.” ABOUT THE AUTHOR • Nov. 10th, 1960 (came into being) • Polish-Jewish origin (born in England) • Early influences: – C.S. Lewis – J.R.R. Tolkien – Ursula K. Le Guin • Pursued journalism as a career, focused on book reviews and rock journalism • 1st book a biography of Duran Duran, 2nd a book of quotations (collaborative) • Became friends with comic book writer Alan Moore & started writing comics GAIMAN’S WORKS • Co-author (with Terry Pratchett) of Good Omens, a very funny novel about the end of the world; international bestseller • Creator/writer of monthly DC Comics series Sandman, won 9 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards and 3 Harvey Awards – #19 won 1991 World Fantasy Award for best short story, 1st comic ever to win a literary award – Endless Nights 1st graphic novel to appear on NYT bestseller list • American Gods in 2001; NYT bestselling novel, won Hugo, Nebula, Bram Stoker, SFX, and Locus awards • Wrote the script for Beowulf with Roger Avary OTHER WORKS • Mirrormask film released in late 2005 • Designed a six-part fantastical series for the BBC called Neverwhere, aired in 1996. The novel Neverwhere was released in 1997 and made into a film. • Coraline and The Wolves in the Walls are two award-winning children’s books; Coraline is being filmed, with music provided by They Might Be Giants, and TWW is being made into an opera. -

2, July 2008 (5 Months Late) Is Edited and Published by Rich Coad, 2132 Berkeley Drive, Santa Rosa, CA 95401

Sense of Wonder Stories 2, July 2008 (5 months late) is edited and published by Rich Coad, 2132 Berkeley Drive, Santa Rosa, CA 95401. e-mail: [email protected] Wondertorial......................................... .........................................page 3 Editorial natterings by Rich Coad The Good Soldier: George Turner as Combative Critic.................page 6 Bruce Gillespie on the well known author and critic A Dream of Flight..........................................................................page 13 Cover artist Bruce Townley on steam driven planes Heresy, Maybe?............................................................................page 16 FAAn Award winner Peter Weston battles James Blish J.G.Ballard A Journey of Inference...............................................page 18 Graham Charnock reminds us how good Mundane SF could be The Readers Write.......................................................................page 22 To get SF fans talking SF simply mention Heinlein Great Science Fiction Editors..................................................back cover Horace Gold: Galaxy Master 2 WONDERTORIAL SF seems to be a literature that thrives upon manifes- Hard to argue with that. Science fiction rooted in sci- toes, written and unwritten, loudly proclaimed for all ence fact - sounds like Campbell’s prescription for As- to inveigh upon, or stealthily applied by editors at large tounding. And the future is here on Earth for most of to shift the field into a new direction. us seems less than controversial He goes on to say Geoff Ryman, a writer of immense talent and ambi- tion as anyone who has read Was will tell you, has fol- “I wrote a jokey Mundane Mani- lowed the loud proclamation route with his provoca- festo. It said let’s play this serious tive call for more mundane SF. It’s difficult to think of game. Let’s agree: no FTL, no FTL a name more calculated to drive the average SF fan communications, no time travel, into a state of copralaliac Tourette’s twitches than no aliens in the flesh, no immortal- “Mundane SF”. -

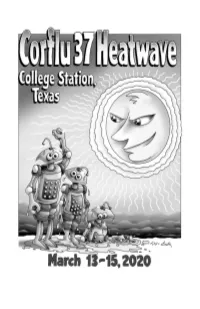

Corflu 37 Program Book (March 2020)

“We’re Having a Heatwave”+ Lyrics adapted from the original by John Purcell* We’re having a heatwave, A trufannish heatwave! The faneds are pubbing, The mimeo’s humming – It’s Corflu Heatwave! We’re starting a heatwave, Not going to Con-Cave; From Croydon to Vegas To bloody hell Texas, It’s Corflu Heatwave! —— + scansion approximate (*with apologies to Irving Berlin) 2 Table of Contents Welcome to Corflu 37! The annual Science Fiction Fanzine Fans’ Convention. The local Texas weather forecast…………………………………….4 Program…………………………………………………………………………..5 Local Restaurant Map & Guide…………..……………………………8 Tributes to Steve Stiles:…………………………………………………..12 Ted White, Richard Lynch, Michael Dobson Auction Catalog……………………………………………………………...21 The Membership…………………………………………………………….38 The Responsible Parties………………………………………………....40 Writer, Editor, Publisher, and producer of what you are holding: John Purcell 3744 Marielene Circle, College Station, TX 77845 USA Cover & interior art by Teddy Harvia and Brad Foster except Steve Stiles: Contents © 2020 by John A. Purcell. All rights revert to contrib- uting writers and artists upon publication. 3 Your Local Texas Weather Forecast In short, it’s usually unpredictable, but usually by mid- March the Brazos Valley region of Texas averages in dai- ly highs of 70˚ F, and nightly lows between 45˚to 55˚F. With that in mind, here is what is forecast for the week that envelopes Corflu Heatwave: Wednesday, March 11th - 78˚/60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Thursday, March 12th - 75˚/ 61˚ F or 24˚/15˚ C Friday, March 13th - 77˚/ 58˚ F or 25 / 15˚ C - Saturday, March 14th - 76˚/ 58 ˚F or 24 / 15˚C Sunday, March 15th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/16˚C Monday March 16th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C Tuesday, March 17th - 78˚ / 60˚ F or 26˚/ 16˚C At present, no rain is in the forecast for that week. -

B a U M a N R a R E B O O

B A U M A N R A R E B O O K S The sixties With Dozens of New Acquisitions! BaumanRareBooks.com 1-800-97-bauman (1-800-972-2862) or 212-751-0011 [email protected] New York 535 Madison Avenue (Between 54th & 55th Streets) New York, NY 10022 800-972-2862 or 212-751-0011 (by appointment due to COVID-19) Las Vegas Grand Canal Shoppes The Venetian | The Palazzo 3327 Las Vegas Blvd., South, Suite 2856 Las Vegas, NV 89109 888-982-2862 or 702-948-1617 Daily: 11am to 7pm Philadelphia 1608 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 215-546-6466 | (fax) 215-546-9064 (by appointment) all booKS aRE ShippEd on appRoval and aRE fully guaRantEEd. Any items may be returned within ten days for any reason (please notify us before returning). All reimbursements are limited to original purchase price. We accept all major credit cards. Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Packages will be shipped by UPS or Federal Express unless another carrier is requested. Next-day or second-day air service is available upon request. www.baumanrarebooks.com twitter.com/baumanrarebooks facebook.com/baumanrarebooks On the cover: Item no. 70. J u l y 2 0 2 0 First Edition Of Manchild In “Everybody was really The Promised Land 1. BROWN, Claude. Manchild in the Promised Land. New York, 1965. Octavo, original red cloth, digging themselves and dust jacket. $800. Click for more info thinking and saying in their First edition of this moving autobiography chronicling one man’s journey out of poverty and crime in Harlem. -

Higgins, David. "New Wave Science Fiction" a Virtual Introduction to Science Fiction

New Wave Science Fiction David Higgins Science fiction's New Wave was a transatlantic avant-garde movement that took place during the 1960s and 1970s, and it had a lasting impact on the genre as a whole. New wave writers were highly experimental, they wanted to develop a modern literary science fiction with advanced aesthetic techniques, and they focused on 'soft' sciences like psychology and sociology rather than 'hard' sciences like physics and astronomy. The movement as a whole sought to subvert the pulp genre conventions that had dominated science fiction since the Golden Age. A wide variety of authors were part of the New Wave movement. Some of them, such as J.G. Ballard, Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. LeGuin, Joanna Russ, and Philip K. Dick have achieved critical attention in the literary mainstream. Many others are known primarily as science fiction writers, and a short list of these includes Brian Aldiss, Barrington J. Bayley, John Brunner, Thomas M. Disch, Harlan Ellison, Philip Jose Farmer, M. John Harrison, Langdon Jones, Damon Knight, Michael Moorcock, Charles Platt, James Sallis, Robert Silverberg, John T. Sladek, Norman Spinrad, Roger Zelazny, and Pamela Zoline. In order to understand the New Wave, it is first useful to understand some of the profound technological, social, and political transformations that were taking place during the 1960s. In the Western world, there was an explosion of new techno- logical advancements during this time, and there were deep disagreements about the consequences of these new technologies. On the more optimistic side, some be- lieved that technological progress would lead mankind out into the stars. -

Ebook < Hugo Award Winning Authors \ Read

Hugo Award winning authors \ Book > JXNG7YCATY Hugo A ward winning auth ors By - Reference Series Books LLC Jun 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x11 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 203. Chapters: Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, J. K. Rowling, Philip K. Dick, Neil Gaiman, Ursula K. Le Guin, Harlan Ellison, Neal Stephenson, Ray Bradbury, Poul Anderson, William Gibson, Larry Niven, Frank Herbert, James Blish, Brian Aldiss, Vernor Vinge, James Tiptree, Jr., Frederik Pohl, Bruce Sterling, Harry Turtledove, Theodore Sturgeon, Roger Zelazny, Cyril M. Kornbluth, Stephen Baxter, Kim Stanley Robinson, J. Michael Straczynski, Jack Vance, Greg Egan, Philip José Farmer, Fritz Leiber, Greg Bear, Robert Bloch, John Brunner, Hal Clement, Anne McCaffrey, Lois McMaster Bujold, Murray Leinster, Joanna Russ, Damon Knight, George R. R. Martin, Charles Sheffield, R. A. Lafferty, Alfred Bester, George Alec Effinger, Dan Simmons, David Brin, John Varley, Joss Whedon, Michael Chabon, Geoffrey A. Landis, Eric Frank Russell, Walter M. Miller, Jr., Alan Moore, Arthur C. Clarke, Clifford D. Simak, Steven Moffat, Samuel R. Delany, Orson Scott Card, Robert J. Sawyer, Octavia E. Butler, Ronald D. Moore, Jack Williamson, Connie Willis, Mike Resnick, Susanna Clarke, China Miéville, C. J. Cherryh, David Gerrold, Robert Silverberg, Ian McDonald, Jane Espenson, Joe... READ ONLINE [ 7.37 MB ] Reviews It is simple in study easier to fully grasp. It is definitely basic but unexpected situations within the fiy percent in the ebook. I am delighted to let you know that this is actually the finest publication i have got read inside my own life and could be he very best ebook for actually. -

V – Version 1 (June 2009)

The Canadian Fancyclopedia: V – Version 1 (June 2009) An Incompleat Guide To Twentieth Century Canadian Science Fiction Fandom by Richard Graeme Cameron, BCSFA/WCSFA Archivist. A publication of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association (BCSFA) And the West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA). You can contact me at: [email protected] Canadian fanzines are shown in red, Canadian Apazines in Green, Canadian items in purple, Foreign items in blue. V VANAPA / VANATIONS / VANCOUVER AREA FLYING SAUCER CLUB / VANCOUVER SF SOCIETY / VATI-CON III PROGRAM BOOK / VCBC BULLETIN / VCON / VELVET GLOVES AND SPIT / VENUS IN CONJUNCTION / VICTORY UPDATE / LA VIEILLE LOBELIA / THE VIEW FROM THE EPICENTRE / VILE PRO / VISIONS / VODKA ON THE ROCKS / VOGON POETRY CONTEST / THE VOICE / VOLDESFAN / VOLTA / VOM - VOICE OF THE IMAGI-NATION / VOMAIDENS / VOMB / VOMBI / VULCAN / VULCAN MAIL VANAPA -- Faneds (O.E.): Fran Skene & Shelly Lewis Gordy. The Vancouver APA, pubbed out of Vancouver, B.C. (Detail to be added) "VANAPA tends to be slightly more frivolous than BCAPA and to discourage political discussions, etc." - (RR) In her editorial in the last VANAPA (#34), Fran Skene wrote: "We have our answer. VANAPA has perished. However, it served a need for a while as a place for locals to turn to when they couldn't stand the arguments in BCAPA." 1978 - (#1 - Dec) 1979 - (#2 - Jan) (#3 - Feb) (#4 - Mar) (#5 - Apr) (#6 - May) (#7 - Jun) (#8 - Jul) (#9 - Aug) (#10 - Sep) (#11 - Oct) (#12 - Nov) (#13 - Dec) 1980 - (#14 - Jan) (#15 - Feb) (#16 - Mar) (#17 - Apr) (#18 - May) (#19 - Jun) (#20 - Jul) (#21 - Aug) (#22 - Sep) (#23 - Oct) (#24 - Nov) (#25 - dec) 1981 - (#26 - Jan) (#27 - Feb) (#28 - Mar) (#29 - Apr) (#30/31 - May/Jun) (#32 - Nov) 1982 - (#33 - Jan) (#34 - Jun) [ See BCAPA ] VANATIONS -- Faned: Norman G. -

Aurora 25 Bogstad & Gomoll 1986-Wi

Issue No 25 Humor & SF Vol. 10 No 1 Winter 1986-87 ISSN 0275-3715 Issue No 25 Humor & SF Vol. 10 No 1 Winter 1986-87 ISSN 0275-3715 Features Subscription Information 2 In tro d u c tio n : On Femi A th re e -is s u e su b sc rip tio n to Aurora nism, S cience F ic tio n , and Humor Diane M artin Is a v a ila b le fo r $10 w ith in the US, 4 Dear E d ito r ia l Horde (L e tte r s ) You Folks or $13 o u tsid e the US. A ll su b scrip 36 C o n trib u to rs ' G a lle ry Themselves tio n s requested a t former ra te s w ill be c re d ite d a t c u r r e n t r a t e s . An Is s u e returned to you because you Articles f a ile d to n o tify us of your change 7 An Open L e tte r to Joanna Russ Jeanne Gomoll o f address reduces your su b sc rip tio n by one iss u e . 11 Humor In S ta r Trek Susan B a ilie tte 2 Back issu e s of Aurora a re a v a ila b le 4 A B rie f Survey of Women In Comics Hank L u ttr e ll fo r $3.50 each, w ith these ex cep tio n s: Issu e #12/13 o r photocopies Reviews of Joanna Russ’s Books of #s 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 11, and 21 cost $5. -

Speculative Fiction Studies

Speculative Fiction Studies “The forceps of our mind are clumsy forceps, and crush the truth a little in taking hold of it.” - H.G. Wells Course Description: Speculative Fiction Studies explores and illuminates a genre apart from, and in some ways broader than, the traditional canon of literary fiction. The goal of this course is to explore in what sense the act of “speculation” is central to all literature, but particularly crucial to this genre, which encompasses what we recognize today as fantasy and science fiction as well as alternative histories and futures, utopias and dystopias. Students will explore the evolution of this lively, diverse genre, and consider how its themes and tropes act as allegories for the problems of the human condition. The course will focus on a variety of short- and long-form readings, with class discussion, individual and group projects, analytical writing, speculative writing, and finally research writing as the avenues of assessment. Students will also be presented with scholarship and literary theory in the field of speculative fiction, the better to understand the deep philosophical, literary, and cultural implications of this genre. INSTRUCTOR: • Tracy Townsend • A115C, on campus from 9:30-4:30 A through D days and by appointment. • 630.907.5954 • [email protected] Meeting Days, Time and Room(s) 9:00-9:55 A, C, D (A116) 1:20-2:15 A, C, D (A116) Text(s) / Materials: You will be expected to bring your current readings (critical essays, short stories, and novellas), whether in paper or .pdf form, to class, and your copies of our core texts as we read and discuss them.