Journal 24Th Issue Final for Ammu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 17 Christian Social Organisation

Social Organisation UNIT 17 CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ORGANISATION Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 Origin of Christianity in India 17.2.1 Christian Community: The Spatial and Demographic Dimensions 17.2.2 Christianity in Kerala and Goa 17.2.3 Christianity in the East and North East 17.3 Tenets of Christian Faith 17.3.1 The Life of Jesus 17.3.2 Various Elements of Christian Faith 17.4 The Christians of St. Thomas: An Example of Christian Social Organisation 17.4.1 The Christian Family 17.4.2 The Patrilocal Residence 17.4.3 The Patrilineage 17.4.4 Inheritance 17.5 The Church 17.5.1 The Priest in Christianity 17.5.2 The Christian Church 17.5.3 Christmas 17.6 The Relation of Christianity to Hinduism in Kerala 17.6.1 Calendar and Time 17.6.2 Building of Houses 17.6.3 Elements of Castes in Christianity 17.7 Let Us Sum Up 17.8 Key Words 17.9 Further Reading 17.10 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 17.0 OBJECTIVES This unit describes the social organisation of Christians in India. A study of this unit will enable you to z explain the origin of Christianity in India z list and describe the common features of Christian faith z describe the Christian social organisation in terms of family, the role of the priest, church and Christmas among Syrian Christians of Kerala z identify and explain the areas of relationship between Christian and Hindu 42 social life in Kerala. Christian Social 17.1 INTRODUCTION Organisation In the previous unit we have looked at Muslim social organisation. -

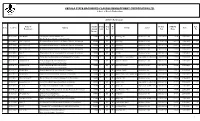

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference

GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 Re-Appraising Taxation in Travancore and It's Caste Interference REVATHY V S Research Scholar Department Of History University Of Kerala [email protected] 8281589143 Travancore , one of the Princely States in British India and later became the Model State in British India carried a significant role in history when analysing its system of taxation. Tax is one of the chief means for acquiring revenue and wealth. In the modern sense, tax means an amount of money imposed by a government on its citizens to run a state or government. But the system of taxation in the Native States of Travancore had an unequal character or discriminatory character and which was bound up with the caste system. In the case of Travancore and its society, the so called caste system brings artificial boundaries in the society.1 The taxation in Travancore is mainly derived through direct tax, indirect tax, commercial tax and taxes in connection with the specific services. The system of taxation adopted by the Travancore Royal Family was oppressive and which was adversely affected to the lower castes, women and common people. It is proven that the system of taxation used by the Royal Family as a tool for oppression and subjugation and they also used this P a g e | 207 Copyright ⓒ 2019 Authors GIS Business ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-14-Issue-3-May-June-2019 discriminatorytaxation policies as of the ardent machinery to establish their political domination and establishing their cultural hegemony. Through the analysis and study of taxation in Travancore it is helpful to reconstruct the socio-economic , political and cultural conditions of Travancore. -

Action Plan Manali12092016.Pdf

Sl. PAGE No No CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Area Details 1 1.2 Location 1 1.3 Digitized map with Demarcation of Geographical Boundaries and Impact Zones 1.4 CEPI Score 2 1.5 Total Population and Sensitive Receptors 2 1.6 Eco-geological features 4 1.6.1 Major Water bodies 4 1.6.2 Ecological parks , Sanctuaries , flora and fauna or any 4 ecosystem 1.6.3 Buildings or Monuments of Historical / 4 archaeological / religious importance 1.7 Industry Classification 5 1.7.1 Highly Polluting Industries 5 1.7.2 Red category industries 6 1.7.3 Orange and Green category industries 6 1.7.4 Grossly Polluting Industries 6 2 WATER ENVIRONMENT 2.1 Present status of water environment 7 2.1.1 Water bodies 7 2.1.2 Present level of pollutants 7 2.1.3 Predominant sources contributing to various 8 pollutant 2.2 Source of Water Pollution 8 2.2.1 Industrial 9 2.2.2 Domestic 9 2.2.3 Others 11 2.2.4 Impact on surrounding area 11 2.3 Details of water polluting industries in the area 11 cluster 2.4 Effluent Disposal Methods- Recipient water bodies 14 2.5 Quantification of wastewater pollution load and relative 17 contribution by different sources viz industrial/ domestic 2.6 Action Plan for compliance and control of Pollution 25 2.6.1 Existing infrastructure facilities 25 2.6.2 Pollution control measures installed by the units 26 2.6.3 Technological Intervention 36 2.6.4 Infrastructural Renewal 37 2.6.5 Managerial and financial aspects 37 2.6.6 Self monitoring system in industries 37 2.6.7 Data linkages to SPCB (of monitoring devices) 37 3 AIR ENVIRONMENT 3.1 Present -

Chapter I Christianity in Kerala: Tracing Antecedents

CHAPTER I CHRISTIANITY IN KERALA: TRACING ANTECEDENTS Introduction This chapter is an analysis of the early history of Christianity in Kerala. In the initial part it attempts to trace the historical background of Christianity from its origin to the end of seventeenth century. The period up to the colonial period forms the first part after which the history of the colonial part is given. This chapter also tries to examine how colonial forces interfered in the life of Syrian Christians and how it became the foremost factor for the beginning of conflicts. It tried to explain about the splits that happened in the community because of the interference of the Portuguese. It likewise deals with the relation of Dutch with the Syrian Christian community. It also discusses the conflict between the Jesuit and Carmelite missionaries. History of Christianity in Kerala in the Pre-Colonial Period Kerala, which is situated on the south west coast of Peninsular India, is one of the oldest centers of Christianity in the world. This coast was popularly known as Malabar. The presence of Christian community in the pre-colonial period of Kerala is an unchallenged reality. It began to appear here from the early days of Christendom.1 But the exact period in which Christianity was planted in Malabar, by whom, how or under what conditions, cannot be said with any confidence. However historians have offered unimportant guesses in the light of traditional legends and sources. The origin of Christianity was subject to wide enquiry and research by scholars. Different contradictory theories have been formulated by historians, religious leaders, and politicians on the Christian proselytizing in India. -

Dress As a Tool of Empowerment : the Channar Revolt

Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Keerthana Santhosh Assistant Professor (Part time Research Scholar – Reg. No. 19122211082008) Department of History St. Mary’s College, Thoothukudi (Manonmanium Sundaranar sUniversity, Tirunelveli) Abstract Empowerment simply means strengthening of women. Travancore, an erstwhile princely state of modern Kerala was considered as a land of enlightened rulers. In the realm of women, condition of Travancore was not an exception. Women were considered as a weaker section and were brutally tortured.Patriarchy was the rule of the land. Many agitations occurred in Travancore for the upliftment of women. The most important among them was the Channar revolt, which revolves around women’s right to wear dress. The present paper analyses the significance of Channar Revolt in the then Kerala society. Keywords: Channar, Mulakkaram, Kuppayam 53 | P a g e Dress as a tool of Empowerment : The Channar Revolt Kerala is considered as the God’s own country. In the realm of human development, it leads India. Regarding women empowerment also, Kerala is a model. In women education, health indices etc. there are no parallels. But everything was not better in pre-modern Kerala. Women suffered a lot of issues. Even the right to dress properly was neglected to the women folk of Kerala. So what Kerala women had achieved today is a result of their continuous struggles. Women in Travancore, which was an erstwhile princely state of Kerala, irrespective of their caste and community suffered a lot of problems. The most pathetic thing was the issue of dress. Women of lower castes were not given the right to wear dress above their waist. -

The Institute of Road Transport Driver Training Wing, Gummidipundi

THE INSTITUTE OF ROAD TRANSPORT DRIVER TRAINING WING, GUMMIDIPUNDI LIST OF TRAINEES COMPLETED THE HVDT COURSE Roll.No:17SKGU2210 Thiru.BARATH KUMAR E S/o. Thiru.ELANCHEZHIAN D 2/829, RAILWAY STATION ST PERUMAL NAICKEN PALAYAM 1 8903739190 GUMMIDIPUNDI MELPATTAMBAKKAM PO,PANRUTTI TK CUDDALORE DIST Pincode:607104 Roll.No:17SKGU3031 Thiru.BHARATH KUMAR P S/o. Thiru.PONNURENGAM 950 44TH BLOCK 2 SATHIYAMOORTHI NAGAR 9789826462 GUMMIDIPUNDI VYASARPADI CHENNAI Pincode:600039 Roll.No:17SKGU4002 Thiru.ANANDH B S/o. Thiru.BALASUBRAMANIAN K 2/157 NATESAN NAGAR 3 3RD STREET 9445516645 GUMMIDIPUNDI IYYPANTHANGAL CHENNAI Pincode:600056 Roll.No:17SKGU4004 Thiru.BHARATHI VELU C S/o. Thiru.CHELLAN 286 VELAPAKKAM VILLAGE 4 PERIYAPALAYAM PO 9789781793 GUMMIDIPUNDI UTHUKOTTAI TK THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601102 Roll.No:17SKGU4006 Thiru.ILAMPARITHI P S/o. Thiru.PARTHIBAN A 133 BLA MURUGAN TEMPLE ST 5 ELAPAKKAM VILLAGE & POST 9952053996 GUMMIDIPUNDI MADURANDAGAM TK KANCHIPURAM DT Pincode:603201 Roll.No:17SKGU4008 Thiru.ANANTH P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER SELVAM S 10/191 CANAL BANK ROAD 6 KASTHURIBAI NAGAR 9940056339 GUMMIDIPUNDI ADYAR CHENNAI Pincode:600020 Roll.No:17SKGU4010 Thiru.VIJAYAKUMAR R S/o. Thiru.RAJENDIRAN TELUGU COLONY ROAD 7 DEENADAYALAN NAGAR 9790303527 GUMMIDIPUNDI KAVARAPETTAI THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601206 Roll.No:17SKGU4011 Thiru.ULIS GRANT P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER G 68 THAYUMAN CHETTY STREET 8 PONNERI 9791745741 GUMMIDIPUNDI THIRUVALLUR THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601204 Roll.No:17SKGU4012 Thiru.BALAMURUGAN S S/o. Thiru.SUNDARRAJAN N 23A,EGAMBARAPURAM ST 9 BIG KANCHEEPURAM 9698307081 GUMMIDIPUNDI KANCHEEPURAM DIST Pincode:631502 Roll.No:17SKGU4014 Thiru.SARANRAJ M S/o. Thiru.MUNUSAMY K 5 VOC STREET 10 DR. -

Catholic Shrines in Chennai, India: the Politics of Renewal and Apostolic Legacy

CATHOLIC SHRINES IN CHENNAI, INDIA: THE POLITICS OF RENEWAL AND APOSTOLIC LEGACY BY THOMAS CHARLES NAGY A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington (2014) Abstract This thesis investigates the phenomenon of Catholic renewal in India by focussing on various Roman Catholic churches and shrines located in Chennai, a large city in South India where activities concerning saintal revival and shrinal development have taken place in the recent past. The thesis tracks the changing local significance of St. Thomas the Apostle, who according to local legend, was martyred and buried in Chennai. In particular, it details the efforts of the Church hierarchy in Chennai to bring about a revival of devotion to St. Thomas. In doing this, it covers a wide range of issues pertinent to the study of contemporary Indian Christianity, such as Indian Catholic identity, Indian Christian indigeneity and Hindu nationalism, as well as the marketing of St. Thomas and Catholicism within South India. The thesis argues that the Roman Catholic renewal and ―revival‖ of St. Thomas in Chennai is largely a Church-driven hierarchal movement that was specifically initiated for the purpose of Catholic evangelization and missionization in India. Furthermore, it is clear that the local Church‘s strategy of shrinal development and marketing encompasses Catholic parishes and shrines throughout Chennai‘s metropolitan area, and thus, is not just limited to those sites associated with St. Thomas‘s Apostolic legacy. i Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my father Richard M. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 27.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Maasi 29, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 553-619 Notice .. 620 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8416. I, Barakathu Nisha, wife of Thiru Syed Ahamed 8419. My son, P. Jayakodi, born on 10th October 2010 Kabeer, born on 1st April 1966 (native district: (native district: Virudhunagar), residing at Old No. 8-23, New Ramanathapuram), residing at Old No. 4-66, New No. 4/192, No. 8-99, West Street, Veeranapuram, Kalingapatti, Chittarkottai Post, Ramanathapuram-623 513, shall henceforth Sankarankoil Taluk, Tirunelveli-627 753, shall henceforth be be known as BARAKATH NEESHA. known as V.P. RAJA. BARAKATHU NISHA. M. PERUMALSAMY. Ramanathapuram, 4th March 2013. Tirunelveli, 4th March 2013. (Father.) 8420. I, Sarika Kantilal Rathod, wife of Thiru Shripal, born 8417. I, S Rasia Begam, wife of Thiru M. Sulthan, born on on 3rd February 1977 (native district: Chennai), residing at 2nd June 1973 (native district: Dindigul), residing at Old No. 140-13, Periyasamy Road, R.S. Puram Post, Coimbatore- No. 4/115-E, New No. -

CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of TAMILNADU Entry No

CENTRAL LIST OF OBC FOR THE STATE OF TAMILNADU E C/Cmm Rsoluti No. & da N. Agamudayar including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 1 Thozhu or Thuluva Vellala Alwar, -do- Azhavar and Alavar 2 (in Kanniyakumari district and Sheoncottah Taulk of Tirunelveli district ) Ambalakarar, -do- 3 Ambalakaran 4 Andi pandaram -do- Arayar, -do- Arayan, 5 Nulayar (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) 6 Archakari Vellala -do- Aryavathi -do- 7 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) Attur Kilnad Koravar (in Salem, South 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Arcot, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 8 Ramanathapuram Kamarajar and Pasumpon Muthuramadigam district) 9 Attur Melnad Koravar (in Salem district) -do- 10 Badagar -do- Bestha -do- 11 Siviar 12 Bhatraju (other than Kshatriya Raju) -do- 13 Billava -do- 14 Bondil -do- 15 Boyar -do- Oddar (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Boya, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Donga Boya, Gorrela Dodda Boya Kalvathila Boya, 16 Pedda Boya, Oddar, Kal Oddar Nellorepet Oddar and Sooramari Oddar) 17 Chakkala -do- Changayampadi -do- 18 Koravar (In North Arcot District) Chavalakarar 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 19 (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 taluk of Tirunelveli district) Chettu or Chetty (including 12011/68/93-BCC(C ) dt 10.09.93 Kottar Chetty, 12011/21/95-BCC dt 15.05.95 Elur Chetty, Pathira Chetty 20 Valayal Chetty Pudukkadai Chetty) (in Kanniyakumari district and Shencottah taluk of Tirunelveli district) C.K. -

Economic and Cultural History of Tamilnadu from Sangam Age to 1800 C.E

I - M.A. HISTORY Code No. 18KP1HO3 SOCIO – ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAMILNADU FROM SANGAM AGE TO 1800 C.E. UNIT – I Sources The Literay Sources Sangam Period The consisted, of Tolkappiyam a Tamil grammar work, eight Anthologies (Ettutogai), the ten poems (Padinen kell kanakku ) the twin epics, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai and other poems. The sangam works dealt with the aharm and puram life of the people. To collect various information regarding politics, society, religion and economy of the sangam period, these works are useful. The sangam works were secular in character. Kallabhra period The religious works such as Tamil Navalar Charital,Periyapuranam and Yapperumkalam were religious oriented, they served little purpose. Pallava Period Devaram, written by Apper, simdarar and Sambandar gave references tot eh socio economic and the religious activities of the Pallava age. The religious oriented Nalayira Tivya Prabandam also provided materials to know the relation of the Pallavas with the contemporary rulers of South India. The Nandikkalambakam of Nandivarman III and Bharatavenba of Perumdevanar give a clear account of the political activities of Nandivarman III. The early pandya period Limited Tamil sources are available for the study of the early Pandyas. The Pandikkovai, the Periyapuranam, the Divya Suri Carita and the Guruparamparai throw light on the study of the Pandyas. The Chola Period The chola empire under Vijayalaya and his successors witnessed one of the progressive periods of literary and religious revival in south India The works of South Indian Vishnavism arranged by Nambi Andar Nambi provide amble information about the domination of Hindu religion in south India.